CERT Hazard Annexes Participant Manual [This Page Intentionally Left Blank] •

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing a Tornado Emergency Plan for Schools in Michigan

A GUIDE TO DEVELOPING A TORNADO EMERGENCY PLAN FOR SCHOOLS Also includes information for Instruction of Tornado Safety The Michigan Committee for Severe Weather Awareness March 1999 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS: A GUIDE TO DEVELOPING A TORNADO EMERGENCY PLAN FOR SCHOOLS IN MICHIGAN I. INTRODUCTION. A. Purpose of Guide. B. Who will Develop Your Plan? II. Understanding the Danger: Why an Emergency Plan is Needed. A. Tornadoes. B. Conclusions. III. Designing Your Plan. A. How to Receive Emergency Weather Information B. How will the School Administration Alert Teachers and Students to Take Action? C. Tornado and High Wind Safety Zones in Your School. D. When to Activate Your Plan and When it is Safe to Return to Normal Activities. E. When to Hold Departure of School Buses. F. School Bus Actions. G. Safety during Athletic Events H. Need for Periodic Drills and Tornado Safety Instruction. IV. Tornado Spotting. A. Some Basic Tornado Spotting Techniques. APPENDICES - Reference Materials. A. National Weather Service Products (What to listen for). B. Glossary of Weather Terms. C. General Tornado Safety. D. NWS Contacts and NOAA Weather Radio Coverage and Frequencies. E. State Emergency Management Contact for Michigan F. The Michigan Committee for Severe Weather Awareness Members G. Tornado Safety Checklist. H. Acknowledgments 2 I. INTRODUCTION A. Purpose of guide The purpose of this guide is to help school administrators and teachers design a tornado emergency plan for their school. While not every possible situation is covered by the guide, it will provide enough information to serve as a starting point and a general outline of actions to take. -

National Weather Service Reference Guide

National Weather Service Reference Guide Purpose of this Document he National Weather Service (NWS) provides many products and services which can be T used by other governmental agencies, Tribal Nations, the private sector, the public and the global community. The data and services provided by the NWS are designed to fulfill us- ers’ needs and provide valuable information in the areas of weather, hydrology and climate. In addition, the NWS has numerous partnerships with private and other government entities. These partnerships help facilitate the mission of the NWS, which is to protect life and prop- erty and enhance the national economy. This document is intended to serve as a reference guide and information manual of the products and services provided by the NWS on a na- tional basis. Editor’s note: Throughout this document, the term ―county‖ will be used to represent counties, parishes, and boroughs. Similarly, ―county warning area‖ will be used to represent the area of responsibility of all of- fices. The local forecast office at Buffalo, New York, January, 1899. The local National Weather Service Office in Tallahassee, FL, present day. 2 Table of Contents Click on description to go directly to the page. 1. What is the National Weather Service?…………………….………………………. 5 Mission Statement 6 Organizational Structure 7 County Warning Areas 8 Weather Forecast Office Staff 10 River Forecast Center Staff 13 NWS Directive System 14 2. Non-Routine Products and Services (watch/warning/advisory descriptions)..…….. 15 Convective Weather 16 Tropical Weather 17 Winter Weather 18 Hydrology 19 Coastal Flood 20 Marine Weather 21 Non-Precipitation 23 Fire Weather 24 Other 25 Statements 25 Other Non-Routine Products 26 Extreme Weather Wording 27 Verification and Performance Goals 28 Impact-Based Decision Support Services 30 Requesting a Spot Fire Weather Forecast 33 Hazardous Materials Emergency Support 34 Interactive Warning Team 37 HazCollect 38 Damage Surveys 40 Storm Data 44 Information Requests 46 3. -

Tornadoes & Funnel Clouds Fake Tornado

NOAA’s National Weather Service Basic Concepts of Severe Storm Spotting 2009 – Rusty Kapela Milwaukee/Sullivan weather.gov/milwaukee Housekeeping Duties • How many new spotters? - if this is your first spotter class & you intend to be a spotter – please raise your hands. • A basic spotter class slide set & an advanced spotter slide set can be found on the Storm Spotter Page on the Milwaukee/Sullivan web site (handout). • Utilize search engines and You Tube to find storm videos and other material. Class Agenda • 1) Why we are here • 2) National Weather Service Structure & Role • 3) Role of Spotters • 4) Types of reports needed from spotters • 5) Thunderstorm structure • 6) Shelf clouds & rotating wall clouds • 7) You earn your “Learner’s Permit” Thunderstorm Structure Those two cloud features you were wondering about… Storm Movement Shelf Cloud Rotating Wall Cloud Rain, Hail, Downburst winds Tornadoes & Funnel Clouds Fake Tornado It’s not rotating & no damage! Let’s Get Started! Video Why are we here? Parsons Manufacturing 120-140 employees inside July 13, 2004 Roanoke, IL Storm shelters F4 Tornado – no injuries or deaths. They have trained spotters with 2-way radios Why Are We Here? National Weather Service’s role – Issue warnings & provide training Spotter’s role – Provide ground-truth reports and observations We need (more) spotters!! National Weather Service Structure & Role • Federal Government • Department of Commerce • National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration • National Weather Service 122 Field Offices, 6 Regional, 13 River Forecast Centers, Headquarters, other specialty centers Mission – issue forecasts and warnings to minimize the loss of life & property National Weather Service Forecast Office - Milwaukee/Sullivan Watch/Warning responsibility for 20 counties in southeast and south- central Wisconsin. -

Preparedness and Partnerships: Lessons Learned from the Missouri Disasters of 2011 a Focus on Joplin

Preparedness and Partnerships: LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE MISSOURI DISASTERS OF 2011 A Focus on Joplin Coordination Incident Command Documentation Communication ESS RES DN PO RE N A S P E E R P R E N C O O I V T E A R G I Y T I M x Preparedness and Partnerships: LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE MISSOURI DISASTERS OF 2011 A Focus on Joplin TABLE OF CONTENTS E xecutive Summary _________________________________________________________ 2 The Missouri Hospital Association as a Response Organization ____________________ 8 Lessons Learned ___________________________________________________________ 10 Planning ______________________________________________________11 Communication _______________________________________________ 21 Resources and Assets __________________________________________ 24 Safety and Security ____________________________________________ 26 Staffing Responsibilities _________________________________________ 29 Staffing ________________________________________________ 29 Volunteers ______________________________________________ 31 Utilities Management __________________________________________ 32 Patient, Clinical and Support Activities ____________________________ 33 Medical Surge ___________________________________________ 33 References and Acknowledgements ___________________________________________ 36 Disclaimer: This report reflects information gathered from many hospital staff through surveys, interviews, presentations and individual and group discussions. The information relates individual and organization-specific identified -

2013 Tornado and Severe Weather Awareness Drill

2013 Tornado and Severe Weather Awareness Drill Scheduled for Thursday April 18, 2013 The 2013 Tornado Drill will consist of a mock tornado watch and a mock tornado warning for all of Wisconsin. This is a great opportunity for your school, business and community to practice your emergency plans. DRILL SCHEDULE: 1:00 p.m. – National Weather Service issues a mock tornado watch for all of Wisconsin (a watch means tornadoes are possible in your area. Remain alert for approaching storms). 1:45 p.m. - National Weather Service issues mock tornado warning for all of Wisconsin (a warning means a tornado has been sighted or indicated on weather radar. Move to a safe place immediately). 2:00 p.m. – End of mock tornado watch/warning drill The tornado drill will take place even if the sky is cloudy, dark and/or rainy. If actual severe storms are expected in the state on Thursday, April 18, the tornado drill will be postponed until Friday, April 19 with the same times. If severe storms are possible Friday, the drill will be cancelled. Information on the status of the drill will be posted at ReadyWisconsin.wi.gov. Most local and state radio, TV and cable stations will be participating in the drill. Television viewers and radio station listeners will hear a message at 1:45 p.m. indicating that “This is a test.” The mock tornado warning will last about one minute on radio and TV stations across Wisconsin and when the test is finished, stations will return to normal programming. In addition, alerts for both the mock tornado watch and warning will be issued over NOAA weather radios. -

Tornado Preparedness Checklist

Tornado Preparedness Checklist A tornado is one of nature’s most destructive storms. Unlike a hurricane or tropical storm, a tornado can develop with little warning, sometimes within minutes of the start of a thunderstorm, leaving little time to react. "e wind associated with a tornado can exceed 300 miles per hour, which can cause catastrophic damage. Every area in the United States has the potential of being impacted by a tornado. Tornadoes peak in the southern states from March to May, and from late spring to early summer in the northern states. "e importance of being prepared for a tornado cannot be overstated. "e following checklist can help you to prepare your business for the e#ects of a tornado. 9 BEFORE THE TORNADO Have a plan to provide emergency noti$cations (warning system) to all employees, clients, visitors and customers in the event of a tornado. Assign the responsibility of monitoring external weather conditions to several employees. Be sure to have adequate coverage for all hours of operation, including accommodations for when these individuals will be out of the o%ce. Determine multiple reliable sources (weather websites, weather blogs, etc.) and tools to monitor real-time weather conditions. Locate multiple locations that can be used for shelter by employees during a tornado. Typically, an interior room with concrete or masonry walls is the safest. Most local $re departments will assist companies in the identi$cation of suitable tornado shelters. Post tornado shelter and evacuation maps in common areas throughout your facility. Identify a separate and unique alarm tone/siren/announcement to notify employees and guests to proceed to the designated tornado shelter. -

City of Kenner Emergency Operations Plan (COKEOP), Augmenting the Basic Plan (BP)

CITY OF KENNER EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN Annex “A” HURRICANE AND STORM PLAN (H&SP) Issued: June 1, 2007 Revised: November 1, 2011 City of Kenner, Louisiana Hurricane and Storm Plan June 1, 2007 I. PURPOSE The purpose of the City of Kenner Hurricane & Storm Plan (hereafter referred to as “Plan” or “H&SP”) is to describe the emergency response of City agencies in the event of a hurricane or severe storm. This document is intended to serve as a guide for the delivery and coordination of governmental services prior to, during, and following a storm incident. The guidelines set forth will facilitate the City’s Emergency Planning Advisory Group (EPAG) and executive’s decision-making regarding preparation, response and management of storm incidents. II. SCOPE This Plan is an administrative directive governing the operations of the City of Kenner, its subordinate agencies and departments. This document in no way purports to cover all aspects of storm related disaster/emergency or recovery management. Rather, it is intended to provide City personnel with an outline of those essential functions and duties to be performed in the event of a hurricane or storm event. - 1 - Revised: November 1, 2011 City of Kenner, Louisiana Hurricane and Storm Plan June 1, 2007 TITLE I. PLAN IMPLEMENTATION III. HURRICANE AND STORM PLAN IMPLEMENTATION The City of Kenner Hurricane and Storm Plan (H&SP) is a component of the City of Kenner Emergency Operations Plan (COKEOP), augmenting the Basic Plan (BP). Upon learning or receiving information from any source of a developing, pending, or actual hurricane or storm event, the Mayor or his/her designee may implement all or any portion of the COKEOP-BP or H&SP. -

Severe Thunderstorms and Tornadoes Toolkit

SEVERE THUNDERSTORMS AND TORNADOES TOOLKIT A planning guide for public health and emergency response professionals WISCONSIN CLIMATE AND HEALTH PROGRAM Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health dhs.wisconsin.gov/climate | SEPTEMBER 2016 | [email protected] State of Wisconsin | Department of Health Services | Division of Public Health | P-01037 (Rev. 09/2016) 1 CONTENTS Introduction Definitions Guides Guide 1: Tornado Categories Guide 2: Recognizing Tornadoes Guide 3: Planning for Severe Storms Guide 4: Staying Safe in a Tornado Guide 5: Staying Safe in a Thunderstorm Guide 6: Lightning Safety Guide 7: After a Severe Storm or Tornado Guide 8: Straight-Line Winds Safety Guide 9: Talking Points Guide 10: Message Maps Appendices Appendix A: References Appendix B: Additional Resources ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Wisconsin Severe Thunderstorms and Tornadoes Toolkit was made possible through funding from cooperative agreement 5UE1/EH001043-02 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the commitment of many individuals at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS), Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health (BEOH), who contributed their valuable time and knowledge to its development. Special thanks to: Jeffrey Phillips, RS, Director of the Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health, DHS Megan Christenson, MS,MPH, Epidemiologist, DHS Stephanie Krueger, Public Health Associate, CDC/ DHS Margaret Thelen, BRACE LTE Angelina Hansen, BRACE LTE For more information, please contact: Colleen Moran, MS, MPH Climate and Health Program Manager Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health 1 W. Wilson St., Room 150 Madison, WI 53703 [email protected] 608-266-6761 2 INTRODUCTION Purpose The purpose of the Wisconsin Severe Thunderstorms and Tornadoes Toolkit is to provide information to local governments, health departments, and citizens in Wisconsin about preparing for and responding to severe storm events, including tornadoes. -

Driving in the Winter Factsheet

Driving in the Winter FactSheet HS04-010B (9-07) Even in Texas the onset of winter can bring severe • Winter Storm Watch winter weather conditions. Employers and employees alerts the public to the who drive for a living need to be aware of how to possibility of a blizzard, drive in winter weather. The leading cause of death heavy snow, freezing rain, during a winter storm is driving accidents and multiple or heavy sleet. vehicle accidents are more likely in severe winter weather conditions. Employers and employees can • Winter Storm Warning is take steps to increase safety while driving in winter issued when a combination of heavy snow, heavy weather. freezing rain, or heavy sleet is expected. • Plan ahead and allow plenty of time for travel. • Winter Weather Advisories are issued when An employer should maintain information on its accumulations of snow, freezing rain, freezing employees’ driving destinations, driving routes, drizzle, and sleet may cause significant and estimated time of arrivals. Drivers should inconvenience and moderately dangerous be patient while driving, because trip time can conditions. increase in winter weather. • Snow is frozen precipitation formed when • Winterize vehicles before traveling in winter temperatures are below freezing in most of the weather. Before driving have a mechanic atmosphere from the earth’s surface to cloud check the following items on vehicles: battery; level. antifreeze; wipers and windshield washer fluid; ignition system; thermostat; lights; flashing • Sleet, also know as ice pellets, is formed when hazard lights; exhaust system; heater; brakes; precipitation or raindrops freeze before hitting defroster; tires (check for adequate tread); and the ground. -

A Background Investigation of Tornado Activity Across the Southern Cumberland Plateau Terrain System of Northeastern Alabama

DECEMBER 2018 L Y Z A A N D K N U P P 4261 A Background Investigation of Tornado Activity across the Southern Cumberland Plateau Terrain System of Northeastern Alabama ANTHONY W. LYZA AND KEVIN R. KNUPP Department of Atmospheric Science, Severe Weather Institute–Radar and Lightning Laboratories, Downloaded from http://journals.ametsoc.org/mwr/article-pdf/146/12/4261/4367919/mwr-d-18-0300_1.pdf by NOAA Central Library user on 29 July 2020 University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, Alabama (Manuscript received 23 August 2018, in final form 5 October 2018) ABSTRACT The effects of terrain on tornadoes are poorly understood. Efforts to understand terrain effects on tornadoes have been limited in scope, typically examining a small number of cases with limited observa- tions or idealized numerical simulations. This study evaluates an apparent tornado activity maximum across the Sand Mountain and Lookout Mountain plateaus of northeastern Alabama. These plateaus, separated by the narrow Wills Valley, span ;5000 km2 and were impacted by 79 tornadoes from 1992 to 2016. This area represents a relative regional statistical maximum in tornadogenesis, with a particular tendency for tornadogenesis on the northwestern side of Sand Mountain. This exploratory paper investigates storm behavior and possible physical explanations for this density of tornadogenesis events and tornadoes. Long-term surface observation datasets indicate that surface winds tend to be stronger and more backed atop Sand Mountain than over the adjacent Tennessee Valley, potentially indicative of changes in the low-level wind profile supportive to storm rotation. The surface data additionally indicate potentially lower lifting condensation levels over the plateaus versus the adjacent valleys, an attribute previously shown to be favorable for tornadogenesis. -

Warning Uses Definition of Terms

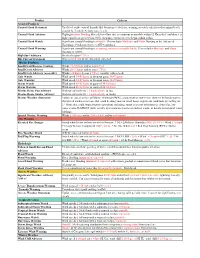

Warning Uses Convective Weather Flooding Winter Weather Non-Precipitation Tornado Watch Flash Flood Watch Blizzard Warning Tornado Warning Flash Flood Warning Winter Storm Watch Severe Thunderstorm Watch Flood Watch Winter Storm Warning High Wind Warning Severe Thunderstorm Warning Flood Warning Snow Advisory Small Stream Flood Freezing Rain Advisory High Wind Advisory Advisory Ice Storm Warning Winter Weather Advisory Definition of Terms Term Definition Winter Weather There is a good chance of a major winter storm developing in the next several days. Outlook Winter Storm Watch There is a greater than 50% chance of a major winter storm in the next several days Winter Storm Any combination of winter weather including snow, sleet, or blowing snow. The Warning snow amount must meet a minimum accumulation amount which varies by location. Blizzard Warning Falling and/or blowing snow frequently reducing visibility to less than 1/4 mile AND sustained winds or frequent gusts greater than 35 mph will last for at least 3 hours. Ice Storm Warning Freezing rain/drizzle is occurring with a significant accumulation of ice (more than 1/4 inch) or accumulation of 1/2 inch of sleet. Wind Chill Warning Wind chill temperature less than or equal to -20 and wind greater than or equal to 10 mph. Winter Weather Any combination of winter weather such as snow, blowing snow, sleet, etc. where Advisory the snow amount is a hazard but does not meet Winter Storm Warning criteria above. Freezing Light freezing rain or drizzle with little accumulation. Rain/Drizzle Advisory . -

KJAX 2018 Product Criteria.Xlsx

Product Criteria Coastal Products Coastal Flood Statement Used to describe coastal hazards that do not meet advisory, warning or watch criteria such as minor beach erosion & elevated (Action) water levels. Coastal Flood Advisory Highlight minor flooding like tidal overflow that is imminent or possible within 12 Hours& if confidence is high (equal to or greater than 50%), then may extend or set to begin within 24 hrs. Coastal Flood Watch Significant coastal flooding is possible. This includes Moderate and Major flooding in the Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service (AHPS) product. Coastal Flood Warning Significant coastal flooding is occurring, imminent or highly likely. This includes Moderate and Major flooding in AHPS. High Surf Advisory Breaker heights ≥ 7 Feet Rip Current Statement When a high risk of rip currents is expected Marine Products Small Craft Exercise Caution Winds 15-20 knots and/or seas 6 Feet Small Craft Advisory Winds 20-33 knots and/or seas ≥ 7 Feet Small Craft Advisory (seas only) Winds< 20 knots & seas ≥ 7 Feet (usually with a swell) Gale Watch Wind speed 34-47 knots or frequent gusts 34-47 knots Gale Warning Wind speed 34-47 knots or frequent gusts 34-47 knots Storm Watch Wind speed 48-63 knots or gusts of 48-63 knots Storm Warning Wind speed 48-63 knots or gusts of 48-63 knots Marine Dense Fog Advisory Widespread visibility < 1 nautical mile in fog Marine Dense Smoke Advisory Widespread visibility < 1 nautical mile in smoke Marine Weather Statement Update or cancel at Special Marine Warning (SMW), a statement on non-severe showers & thunderstorms, short-lived wind/sea increase that could be dangerous for small boats, significant conditions prevailing for 2+ Hours that could impact marine operations including: rough seas near inlets/passes, dense fog, low water events, HAZMAT spills, rapidly increasing/decreasing or shifting winds, or details on potential water landings.