Learning for Excellence: Professional Learning for Learning Support

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Generation Gap: a Comparison of the Negative Portrayals of Hippies and Generation Xers

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Presidential Scholars Theses (1990 – 2006) Honors Program 1995 The generation gap: A comparison of the negative portrayals of hippies and Generation Xers Greg Becker University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1995 Greg Becker Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pst Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Becker, Greg, "The generation gap: A comparison of the negative portrayals of hippies and Generation Xers" (1995). Presidential Scholars Theses (1990 – 2006). 39. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pst/39 This Open Access Presidential Scholars Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presidential Scholars Theses (1990 – 2006) by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Generation Gap: A comparison of the negative portrayals of Hippies and Generation Xers Presented by: Greg Becker March 15, 1995 Presidential Scholars Senior Project Generation Gap 1 ABSTRACT The term "generation gap" is usually used to describe a situation in which a division develops between generations. The tension results from one generation, usually the younger generation, possessing a set of values and beliefs that are consistently different from the values and beliefs of another generation, usually the older generation. A comparison of newspaper articles concerning both Hippies and Generation Xers was conducted to illustrate the contention that generational conflict occurs in a cyclical pattern with each successive generation. The older generation usually portrays the younger generation in a negative manner. -

Controversy 11

Controversy 11 AGING BOOMERS Boom or Bust? WHO ARE THE BOOMERS? When you hear the word “Boomer,” what do you think of? Who are the Boomers, actually? It’s important to give an answer to both questions. On the one hand, we need to consider the subjective associations we have with the word “Boomer.” On the other hand, we need to consider verifiable facts. The term “Boomer” easily evokes stereotypes. Stereotypes are con- veyed by many of the names given to Boomers over the years, labels such as “The Pepsi Generation,” “The Me Generation,” or “The Sixties Generation.” These phrases convey con- sumerism, narcissism, rebellion, and openness to change. Even the original term “Baby Boomer” doesn’t seem quite right because people in this generation aren’t babies anymore. The oldest of the Boomers are already receiving Social Security benefits, and many others are thinking seriously about retirement. Some facts are clear. There were 77 million people born in the United States between the years 1946 and 1964, and this group of people is generally referred to as the generation of the Boomers. We can see this group graphically displayed as a bulge in the population pyramid featured here. As the Boomer generation moves through the life course, as they grow older, this demographic fact will have big implications over the coming decades. But here we should pause to consider several interrelated questions. What does the term “generation” really mean? Do all individuals who fit into this demographic group form a single “generation”? Are there traits they share in common? Conversely, are there differences among members of the Boomer generation? This is but one set of questions we need to consider. -

Emerging Challenges of HRM in 21St Century: a Theoretical Analysis

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2017, Vol. 7, No. 3 ISSN: 2222-6990 Emerging Challenges of HRM in 21st Century: A Theoretical Analysis Shuana Zafar Nasir Lecturer, Department of Management Science Yanbu University College-Female Campus, Saudi Arabia Email: [email protected]/[email protected] DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i3/2727 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i3/2727 ABSTRACT Human Resource Management discipline extracted its roots from organizational psychology discipline and proved to be an important practice for managing organizations. The role of this practice has emerged to be strategic with due course of time. In an organization, HR has become an important strategic partner and the management of the same has become a challenging task for HR managers. Now a day, the role of human resource management departments has become indispensable for 21st century modern businesses. This article particularly focuses on changing role of human resource management practices in 21st century. This theoretical paper aims to highlight the importance of human resource managers, HR practices and its influencing factors. In addition to that, this article also elaborates the upcoming challenges which are being faced by 21st century HR managers. The literature analysis has been conducted to present emerging issues, challenges and practices of human resource management discipline in context of 21st century. Key Words: Globalization, Strategic Partner, Competency Framework, Technological Advancement, Dynamic Environment, Change Management. INTRODUCTION Companies that aspire to sustain their competitive edge, both at present and in the future require human force well equipped with recent techniques and technologies to face the changes and upcoming challenges of 21st century. -

Exploring Generational Differences in Text Messaging Usage and Habits Daniel Wayne Long Nova Southeastern University, [email protected]

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks CEC Theses and Dissertations College of Engineering and Computing 2018 Exploring Generational Differences in Text Messaging Usage and Habits Daniel Wayne Long Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] This document is a product of extensive research conducted at the Nova Southeastern University College of Engineering and Computing. For more information on research and degree programs at the NSU College of Engineering and Computing, please click here. Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/gscis_etd Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Computer Sciences Commons, Digital Communications and Networking Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation Daniel Wayne Long. 2018. Exploring Generational Differences in Text Messaging Usage and Habits. Doctoral dissertation. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, College of Engineering and Computing. (1060) https://nsuworks.nova.edu/gscis_etd/1060. This Dissertation is brought to you by the College of Engineering and Computing at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in CEC Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Exploring Generational Differences in Text Messaging Usage and Habits By Daniel W. Long A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Information Systems College of Engineering and Computing Nova Southeastern University 2018 2 APPROVAL PAGE 3 An Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to Nova Southeastern University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Exploring Generational Differences in Text Messaging Usage and Habits By Daniel W. -

Generation Y: Investigation of Their Role in the Contemporary Life Conditions and Job Market

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Vol 9 No 3 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) Social Sciences May 2018 Research Article © 2018 Argiro et.al.. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Generation Y: Investigation of Their Role in the Contemporary Life Conditions and Job Market Adamou Argiro1, M.A. Katsarou Danai-Eleni1, M.A. Koffas Stefanos1*, Dr. Aspridis George1, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Tsiotas Dimitrios2, Dr. Sdrolias Labros1, Prof. Dr. 1Department of Business Administration, Technological Educational Institute of Thessaly, Larissa-Greece 2Polytechnic School, University of Thessaly, Volos-Greece *Corresponding Author Doi: 10.2478/mjss-2018-0044 Abstract Human evolution in connection with contemporary globalization has created a new Generation: Generation Y. It consists of young people with specific qualitative characteristics and abilities, as well as a broad-minded and extrovert approach to their lives. Nevertheless, they were unlucky enough to be born and grow up in a period of intense economic crises and social upheaval. As a result they face, especially now, the spectrum of the total breakdown of job prospects and established labour rights; consequently they resort to the less frustrating reflection, that of obligatory migration. In order to better understand this Generation it was deemed necessary to develop and send a questionnaire to young people in Greece and abroad. The use and analysis of the research provides the opportunity to form a complete picture of the extent and manner in which the economic and social uncertainty influenced the development of their character, the differences in their mentality, as well as their true opinion of their own generation. -

Generations Defined

Generations Defined Baby Boomers (1946-1954): These are the children of “The Greatest Generation” as Tom Brokaw named them, born after World War II. This is the first generation that had wide spread access to higher education. Their world view was shaped by the space race, sexual freedom, social movements and the assassinations of JFK and Martin Luther King Jr. Their critical years for joining the work force – between the mid-1960s and the end of the 1970s – were a period when most countries enjoyed significant progress. This led to great expectations of success. Currently, this group occupies positions of higher corporate responsibility and has the largest proportion of workaholics in history. Generation Jones (1954-1965): You might not be too familiar with the younger cohort of Boomers by name because they have generally been lumped together. However, with the election of Barack Obama, born in 1961, this historically overlooked generation has gained new prominence. Members of Generation Jones were young children during the Summer of Love and missed the protests for civil rights and Vietnam. They did, however, experience Watergate, the Cold War and the Cuban Missile Crisis. This generation is so populous that the competition of “Keeping up with the Joneses” ensued. This generation also popularized the slang term, jonesing, meaning “to crave”. Generation X (1965-1979): Coined by author Douglas Coupland in 1991, this generation was shaped by the end of the Cold War, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the first Gulf War. They were the first “latch key kids” since both their parents worked and they were told to “Just Say No!” They were shaped by the Reagan presidency, the AIDS epidemic, the recession of the early ‘90s and the advent of mass media. -

Generations FRM18

Thinking About Different Generations Why does it matter? !1 !2 WHAT’S YOUR GENERATION AND WHY DOES IT MATTER? In society today use of generalizations is common in many situations. Describing the spectrum of population cohorts is one used by both demographers and market researchers. You can better understand the needs and desires of those population groups if you know a little about their background and their realities/norms. !3 Who are we? In Sweet Adelines chapters, we now have SIX socially identified generations – The same challenge facing many work environments today! MIXED AGES PHOTOS !5 What are these groups? GI GENERATION also known as the BUILDERS Born 1928-1945 (ages 73+) BABY BOOMERS – Born 1946-1954 (ages 64-72) BOOMERS II - Generation Jones Born 1955-1965 (ages 53-63) GENERATION X – Born 1966-1976 (ages 42-52) GENERATION Y-Millenials – Born 1977-1994 (ages 24-41) iGen - GENERATION Z – Born 1995-2012 (ages 8-23) !6 Region #10 Membership For this presentation, a snapshot as of 09/04/18 included 635 members, with 17 dual members counted in both of their choruses. 30 members have none or impossible birthdates on file with SAI Headquarters and thus are not included in the following statistics, giving us 595 included members. !7 Region #10’s membership: 595 Members # of Region 10 Ages % of Region 10 GI Generation 103 73+ 17.14% Baby Boomers 191 64-72 32.1% Boomers II 169 53-63 28.4% Gen X 47 42-52 7.9% Gen Y 68 24-41 11.4% iGen/Gen Z 17 Under 23 2.86% 595 !8 While all designations are generalizations, here are a few details that show how demographers describe/define these groups. -

Meeting the Demands of the Smarter Consumer

IBM Global Business Services Retail Executive Report IBM Institute for Business Value Meeting the demands of the smarter consumer IBM Institute for Business Value IBM Global Business Services, through the IBM Institute for Business Value, develops fact-based strategic insights for senior executives around critical public and private sector issues. This executive report is based on an in-depth study by the Institute’s research team. It is part of an ongoing commitment by IBM Global Business Services to provide analysis and viewpoints that help companies realize business value. You may contact the authors or send an e-mail to [email protected] for more information. Introduction By Melissa Schaefer and Laura VanTine New technologies and socioeconomic trends are reshaping the retail marketplace. The IBM Institute for Business Value recently surveyed over 30,000 people in three mature and three growth markets to discover what consumers will want from retailers in the future. We now know that consumers are getting smarter…and understand how their preferences vary across generations, countries and shopping segments. The rules of the retail marketplace are changing dramatically. • Smarter consumers use social networking. Thirty-three percent With the development of new technologies for bidirectional of respondents are likely to “follow” a retailer on a social communication, consumers can get more information about networking site. Some of these people also swap notes, so a retailers and their products more easily than ever before. Mass single consumer’s shopping experience can influence the urbanization and increasing affluence are simultaneously giving decisions many others make about what to buy and where to consumers in the emerging world greater economic power. -

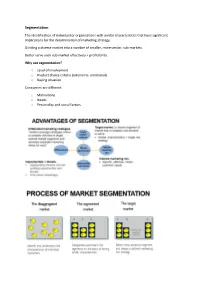

Segmentation

Segmentation The identification of individual or organisations with similar characteristics that have significant implications for the determination of marketing strategy. Dividing a diverse market into a number of smaller, more similar, sub-markets. Better serve each sub-market effectively + profitability. Why use segmentation? o Level of involvement o Product choice criteria (rational vs. emotional) o Buying situation Consumers are different o Motivations o Needs o Personality and social factors Age-based segmentation Sharing similar experiences and engage in shared cultural references. Two types: - Life stage - Generational ‘Defining moments’ influence values, preferences, attitudes and buying behaviour in ways that remain with them over their entire lifetime. Millennials (Generation Y) Millennials -> growing up in the new millennium. Debate what year groups • Born between 1980 – 2000 • Or born between 1983 – 1995 • Termed Gen Y when they gained spending powers as teenagers Characteristics: § Powerful economic demographic § Technologically orientated § More brand loyal § Expect instant access to information Generation Z Born after 1995 – 2012 Characteristics: § Grown-up with digital technology § Consume via smartphones, not TV § Comfortable with gender ambiguity § Congregate in visual social media § Engage with authenticity or idealised lifestyles § Uniqueness and creativity is key Tweens and teens Tweens -> usually between 8 – 12 years old - Consumers in training - Beginning to make independent purchases Teens -> all youths 13 – 18 -

Digital Skills Development for Future Needs of the Canadian Labour Market

Executive Summary: Digital Skills Development for Future Needs of the Canadian Labour Market 1.1 Context – The issue Today’s labour market relies heavily on technology in a multitude of ways and requires skills and competencies that may vary from simply using an online form to apply for work to writing a sophisticated computer program involving virtual environments. With this broad spectrum of workplace demands in mind, we synthesized our research findings to focus on job skills that involve digital systems and tools and on the anticipated changes digital technologies will have on working and learning conditions of Canadians. In the Institute for the Future (2011) report, out of six key drivers that the Institute considers as most relevant to the workforce of the future, at least five relate to technology: (a) collaboration and co-dependence between humans and machines, (b) working with data and patterns, (c) communicating in diverse multimedia forms, (d) tapping into social intelligence, and (e) living in a globally connected and interdependent world. Similarly, the ten skills that the Institute highlights as crucial for the future workforce are all related to technology (e.g., novel and adaptive thinking, virtual collaboration, design mindset). Recent national media reports have made the case that education needs to shift towards lifelong learning and retraining since Canadians overall have scored low in literacy, numeracy, data/quantitative literacy, and technological skills, thus creating a mismatch with anticipated labour market needs (Maclean’s on Campus, 2013). The Canadian Chamber of Commerce predicts that if these trends continue, by 2021, Canada may have a million of unskilled and unemployable workers (CCC, 2012). -

Never Mind the Gap! Digital Differences Among Students and Teachers

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. Tesic, Z. (2016) Never mind the gap! Digital differences between students and teachers. Ed.D. thesis, Canterbury Christ Church University. Contact: [email protected] Never Mind the Gap! Digital Differences among Students and Teachers by Zoran Tešić Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Education Year 2016 In loving memory of my mother, Nada (rođ. Gašić) Tešić. ABSTRACT Although there has been an increase in the availability of digital technology and related media (DT&RM) in many educational institutions across the UK, it has been frequently suggested that the barrier to the successful development of an effective digital learning environment is teachers’ (digital immigrants) lack of technological proficiency to take into account the needs of the new digital -

The Generations of Baby Boomer to Generation Z As Defined in Consumer Culture

The Generations of Baby Boomer to Generation Z as Defined in Consumer Culture by Elizabeth Ciechanowski B.A. in Art History, January 2010, Temple University A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art May 15, 2015 Thesis directed by Clare Brown Program Head in the GW Corcoran School of the Arts and Design Assistant Professor of Art and Design Nigel Briggs Professor of Exhibition Design Cory Bernat Professor of Exhibition Design © Copyright 2015 by Elizabeth Ciechanowski All rights reserved ii Dedications I would like to dedicate this thesis to my family for all the support they have given, and continue to give me. To my thesis mentor John Alviti, and to the thesis advisors; Clare Brown, Cory Bernat, and Nigel Briggs for all of their guidance. iii Abstract The Generations of Baby Boomer to Generation Z As Defined in Consumer Culture. Exhibition Title: Marketing History: Baby Boomer to Generation Z This proposed exhibition, Marketing History: Baby Boomer to Generation Z brings together the sights, sounds, and voices of generations through the medium of advertising and consumer products. Beginning in the 1950s, this exhibition will follow the generations of Baby Boomer, Generation Jones, Generation X, the Millennials, and Generation Z from their coming of age. The exhibition will juxtapose the history and consumer culture of each era with the advertisements, slogans, commercials, and products of the time in an immersive and interactive game-like environment. Precedents include museum exhibitions, retail spaces, radio programming, trade shows, festivals, and world expositions.