Monument Types (Forms)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annex A1 SCNDP Submission Version , Item 3. PDF 3 MB

South Cerney Neighbourhood Plan TTTABLE OF CCCONTENTS Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................ 1 Acknowledgements: ............................................................................................................................ 2 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 Neighbourhood Planning ..................................................................................................................... 3 The South Cerney Neighbourhood Plan 2021 – 2031 ........................................................................... 3 2 Background to the Parish ................................................................................................................. 4 2.1 History and Conservation ......................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Landscape ................................................................................................................................ 6 2.3 Socio Economic Profile ............................................................................................................. 7 2.4 Employment and Services ........................................................................................................ 9 3 Vision ........................................................................................................................................... -

Defibrillators in the Cirencester Area (GL7)

Defibrillators in the Cirencester Area (GL7) Location Location detail Location Area Post Code Ampney Crucis Primary School School Lane School Lane Ampney Crucis GL7 5SD Ampney Crucis Village Hall Main Street Ampney Crucis GL7 5RY Friends of Ampney St Mary Ampney St Mary Red Telephone Box Ampney St Mary GL7 5SP Bibury Trout Farm Rack Isle Building Bibury GL7 5NL 31 Morestall Drive Fixed to outside of building Chesterton Cirencester GL7 1TF Ashcroft Church Fixed to outside of building Ashcroft Road Cirencester GL7 1RA Baunton Telephone Box Baunton 7 Mill View Cirencester GL7 7BB Bibury Football Club Bibury Aldsworth Road Cirencester GL7 5PB Chesterton Primary School Apsley Road Entrance Hall Cirencester GL71SS Cirencester Baptist Church Fixed to outside of building Chesterton Lane Cirencester GL7 1YE Cirencester College (David Building) Stroud Road Cirencester GL7 1XA Cirencester Deer Park School Stroud Road Sports Department Cirencester GL7 1XB Cirencester Deer Park School Stroud Road Caretaker's Office Cirencester GL7 1XB Coln St Aldwyn Telephone Box Coln St Aldwyns Outside Old Post Office Cirencester GL7 5AA Dot Zinc Cecily Hill The Castle Cirencester GL7 2EF Housing 21 - Mulberry Court Middle Mead Cirencester GL7 1GG Kemble and Ewen The Tavern Kemble Station Road Cirencester GL7 6AX Market Place On railing by Noticeboard Market Place Cirencester GL7 2NW Masonic Hall The Avenue Cirencester GL7 1EH Last Updated: 18/07/19 Defibrillators in the Cirencester Area (GL7) Location Location detail Location Area Post Code Morestall Drive 31 Morestall -

Village Life November 2020

VILLAGE LIFE DATES FOR THE DIARY ISSUE No 453 NOVEMBER Sunday 1st Ignite All Saints Halloween Light party, St Mary’s Bibury 5-6.30pm Monday 2nd All Souls Holy Communion and remembrance of the Faithful Departed at St Mary’s Bibury 6:15pm Sunday 8th Remembrance Sunday – various Acts of Remembrance and venues Saturday 5th Advent Craft Fayre; St. Mary’s Bibury 10.30am – 3.30pm Wednesday 25th Chin wag and tea in the chapel 2 -3pm all welcome, social distance in place DECEMBER Saturday 5th Chin wag Christmas Coffee morning and sale, Baptist Church 10.30am Sunday 5th Talk by Hope Price on Modern Day Angels, Baptist Church THOUGHT FOR THE MONTH. If you can dream - and not make dreams your master; if you can think - and not make thoughts your aim; If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster; and treat those two impostors just the same; Yours is the Earth and everything that's in it, (from ‘If’; Rudyard Kipling) FROM THE PANEL - CHRISTMAS IS A-COMING Next months issue will be our Christmas Issue and at present we do not have a suitable sketch for December. Why not have a go and do a drawing in black or blue ink about 15cm square to grace our front cover. Line drawings are preferred and colours and shading do not usually reproduce well with the Village Life technology. Please put your contributions into the Village Life folder at the Trout Farm or email them to [email protected] by November 20th together with your name and age if you are a child! There is no need to give your age if you are an adult! All are welcome! We normally print our annual accounts in this months issue but because of covid we have suspended the charges for adverts and the postal copies until the new year. -

Croome Collection Coventry Family History

Records Service Croome Collection Coventry Family History George William Coventry, Viscount Deerhurst and 9th Earl of Coventry Born 1838, the first son of George William (Viscount Deerhurst) and his wife Harriet Anne Cockerell. After the death of their parents, George William and his sister, Maria Emma Catherine (who later married Gerald Henry Brabazon Ponsonby), were brought up at Seizincote, but they visited Croome regularly. He succeeded as Earl in 1843, aged only 5 years old. During his minority his great-uncle William James (fifth son of the 7th Earl and his wife 'Peggy') took responsibility for the estate, with assistance from his guardians and trustees: Richard Temple of the Nash, Kempsey, Worcestershire and his grandfather, Sir Charles Cockerell. When the 9th Earl came of age at 21 he let William James and his wife Mary live at Earls Croome Court rent- free for the rest of their lives. George William married Lady Blanche Craven (1842-1930), the third daughter of William Craven, 2nd Earl Craven of Combe Abbey, Warwickshire. Together they had five sons: George William, Charles John, Henry Thomas, Reginald William and Thomas George, and three daughters: Barbara Elizabeth, Dorothy and Anne Blanche Alice. In 1859 George William was elected as president of the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC). In 1868 he was invited to be the first Master of the new North Cotswold Hunt when the Cotswold Hunt split. He became a Privy Councillor in 1877 and served as Captain and Gold Stick of the Corps of Gentleman-at-Arms from 1877-80. George William served as Chairman of the County Quarter Sessions from 1880-88. -

'321 Du I.A.P

I.A.P. Rapporten 2 .'321 DU I.A.P. Rapporten uitgegeven door I edited by Prof Dr. Guy De Boe VIOE bibliotheek 5347 11111111 ~ • 1 l~ a " a l • 1 ' W.T A l V ediled :'-, ppori\-:n 2 Ze11il< 1997 Een uitgave van het Published by the Instituul voor het Archeologisch Patrimonium Institute for the Archaeological Heritage Wetenschappelijke instelling van de Scientific Institution of the Vlaamse Gemeenschap Flemish Community Departement Leefmilieu en Infrastructuur Department of the Environment and Infrastructure Administratie Ruimtelijke Ordening, Huisvesting Administration of Town Planning, Housing en Monumenten en Landschappen and Monuments and Landscapes Doornvcld Industrie Asse 3 nr. 1 1, Bus 30 B -1731 Zcllik- Asse Tcl: (02) 463. LU3 1- 32 2 -163 13 33) fax: (02) 463.19.'1 1-.12 2-163 19 511 DTP: Arpuco. Seer.: !Vi. Lauwaert & S. Van de Voorde. ISSN 13 72-0007 ISBN 90-75230-03-6 D/1997/6024/2 02 DEATH AND BURIAL- DE WERELD VAN DE DOOD-LE MONDE DE LA MORT- TOD UND BEGRA!!NIS was organized by Gisela Grupe werd georganiseerd door Willy Dezuttere fut organisee par wurde veranstaltet von PREFACE Death and some fonn of burial are common to all milians-Universitiit, Munchcn) and Willy Dezuttere humankind and the very nature of the disposal of (City of Bruges). Unfortunately, quite a few contri human remains as well as the behavioural patterns - butors to this section did submit a text in time for social, economic, political and even environmental - inclusion in the present volume. In addition, ceme linked with this important passage in human life teries played an important part in the development and makes it a subject of direct interest to archaeology. -

Upper Farm Barn

Upper Farm Barn Coln rogers • glo ucestershire Upper Farm Barn Coln rogers • glo ucestershire northleach 4 miles • Cirencester 7 miles • Burford 13 miles • Cheltenham 14 miles • oxford 31 miles • Kemble station 10 miles (trains to london paddington from 75 mins) (all distances and time are approximate). a superbly presented grade 11 barn conversion in the sought after Coln Valley. Main Accommodation: Drawing room • snug • Kitchen/dining room • study • Utility/boot hall master bedroom and ensuite bathroom • guest bedroom and ensuite bathroom • 1 further ensuite bedroom and 2 further bedrooms Family bathroom • Cloakroom • Boiler/plant room. The Priest House: Kitchen/living area • Bathroom • Bedroom. Gardens and grounds: Courtyard • orchard • open garaging • terrace • Kitchen garden • lawns • Fields. in all about 2.1 acres Lot 2 The Old Stables: Kitchen/living area • Drawing room • Utility room • Cloakroom 3 bedrooms (1 en-suite) • family bathroom. Lot 3 pasture Field with road frontage extending in all to about 7.69 acres In all about 10 acres CIrenCeSTer COunTry DeparTMenT CIrenCeSTer COunTry DeparTMenT 1 Castle street, market place 33 margaret street gloucester house, 60 Dyer street 55 Baker street Cirencester gl7 1QD london W1g 0JD Cirencester, gloucestershire gl7 2pt london W1U 8an [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] tel +44 1285 627550 tel +44 20 7016 3820 tel +44 1285 659771 tel: +44 20 7861 1707 these particulars are only as a guide and must not be relied on as a statement of fact. Your attention is drawn to the important notice on the last page of text. -

Gable Cottage

GABLE COTTAGE MEYSEY HAMPTON, GLOUCESTERSHIRE Fairford 2 miles, Cirencester 7 miles, Lechlade 7 miles, DESCRIPTION Cheltenham 22 miles, Oxford 30 miles, Kemble mainline Gable Cottage is a charming double fronted Cotswold station 11 miles (London Paddington 85 minutes) stone property believed to date back to the 18th Century. Swindon mainline station 15 miles (London Paddington Character features include window seats, exposed beams from 49 minutes, Bristol Temple Meads from and timbers, cottage style internal doors and a splendid 39 minutes) (All times & mileages approximate) stone fireplace with a log burning stove. It is a tastefully presented comfortable home with recent improvements A BEAUTIFULLY PRESENTED including landscaping of the courtyard garden and a stylish fitted kitchen. ATTACHED TWO BEDROOM PERIOD COTTAGE WITH A WEST FACING COURTYARD GARDEN, IN THE HEART OF THIS ATTRACTIVE COTSWOLD VILLAGE. Ground Floor: Entrance Porch • Sitting Room • Kitchen/ Breakfast Room • Rear Lobby First Floor: Two Double Bedrooms • Bathroom • Boarded Attic Space Outside: Front Courtyard Garden • Side Access • Bin Store • Log Store Cirencester office: 43-45 Castle Street, Cirencester, Gloucestershire, GL7 1QD T 01285 883740 E [email protected] www.butlersherborn.co.uk The London Office:40 St James’s Place, London, SW1A 1NS. T 0207 839 0888 E [email protected] www.tlo.co.uk ACCOMMOdaTION houses surrounding the village green, which also boasts an impressive 17th Century Inn. The village primary school is rated Ground Floor Outstanding by Ofsted and there is a fine 13th Century church, The front door opens into an entrance porch, with a door as well as a wonderful and extensive network of footpaths and leading to the welcoming sitting room, which has exposed bridleways across neighbouring countryside. -

5406 Green Infrastructure Open Space

COTSWOLD DISTRICT GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE OPEN SPACE AND PLAY SPACE STRATEGY 201 Open Spaces 4 There is considered to be three main Green Corridors in Fairford, 1) River Coln, 2) Pitman Brook and 3) the PROW from town to lake 104Fairford is well served with PROW and permissive paths, many of which are kept in good condition. There are areas of the footpath along the Coln that are in a state of disrepair and require urgent action to stop the bank from further degeneration. Lovers Walk requires resurfacing. Typology Quantity & Size Accessibility Quality Summary Green Corridors 1) Mix of PROW, 1) Mix of PROW, Essential - All are clean permissive path & permissive path & private. and litter free 1) River private. Coln 2) Permissive Path (closed E - (1) has clearly defined 2) Permissive Path every Tuesday) footpaths with a level 2) Pitman (closed every Tuesday) surface (2) & (3) defined Brook 3)Public access footpath, but not level. 3)Public access 3) PROW from E - All have nature features Path the town to lake 104 Desirable - All have appropriate signage D - All sites don't have multiple use, only walking D - All have no dog/litter bins X - (1) has disabled access in places (2) & (3) not X - 1, 2 & 3 have staff or volunteer involvement. Total amount of accessible space 17,728 metres Total amount of accessible space within 2 KM 17,728 metres (includes Public Rights of Way with 2 KM radius) Total amount of accessible space within 300m NA Findings Green Corridors Quantity and Accessibility: There is no requirement to set catchments for green corridors due to their linear nature. -

Cirencester Road, South Cerney 2015

COTSWOLD DISTRICT COUNCIL Dated 26th March 2015 COTSWOLD DISTRICT COUNCIL TREE PRESERVATION ORDER NO 15/00002 Cirencester Road, South Cerney 2015 Town and Country Planning Act 1990 The Town and Country Planning (Tree Preservation)(England) Regulations 2012 TREE PRESERVATION ORDER relating to Cirencester Road, South Cerney Trinity Road, Cirencester, Gloucestershire, GL7 IPX Tel: 01285 623000 Fax: 01285 623900 www.cotswold.gov.uk TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (TREE PRESERVATION)(ENGLAND) REGULATIONS 2012 COTSWOLD DISTRICT COUNCIL TREE PRESERVATION ORDER NO 15/00002 Cirencester Road, South Cerney 2015 The Cotswold District Council, in exercise of the powers conferred on them by section 198 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 make the following Order- Citation 1. This Order may be cited as TPO 15/00002 Cirencester Road, South Cerney 2015 Interpretation 2. (1) In this Order "the authority" means the Cotswold District Council. (2) In this Order any reference to a numbered section is a reference to the section so numbered in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and any reference to a numbered regulation is a reference to the regulation so numbered in the Town and Country Planning (Tree Preservation)(England) Regulations 2012. Effect 3. (1) Subject to article 4, this Order takes effect provisionally on the date on which it is made. (2) Without prejudice to subsection (7) of section 198 (power to make tree preservation orders) or subsection (1) of section 200 (tree preservation orders: Forestry Commissioners) -

Doorway to Devotion: Recovering the Christian Nature of the Gosforth Cross

religions Article Doorway to Devotion: Recovering the Christian Nature of the Gosforth Cross Amanda Doviak Department of History of Art, University of York, York YO10 5DD, UK; [email protected] Abstract: The carved figural program of the tenth-century Gosforth Cross (Cumbria) has long been considered to depict Norse mythological episodes, leaving the potential Christian iconographic import of its Crucifixion carving underexplored. The scheme is analyzed here using earlier ex- egetical texts and sculptural precedents to explain the function of the frame surrounding Christ, by demonstrating how icons were viewed and understood in Anglo-Saxon England. The frame, signifying the iconic nature of the Crucifixion image, was intended to elicit the viewer’s compunction, contemplation and, subsequently, prayer, by facilitating a collapse of time and space that assim- ilates the historical event of the Crucifixion, the viewer’s present and the Parousia. Further, the arrangement of the Gosforth Crucifixion invokes theological concerns associated with the veneration of the cross, which were expressed in contemporary liturgical ceremonies and remained relevant within the tenth-century Anglo-Scandinavian context of the monument. In turn, understanding of the concerns underpinning this image enable potential Christian symbolic significances to be suggested for the remainder of the carvings on the cross-shaft, demonstrating that the iconographic program was selected with the intention of communicating, through multivalent frames of reference, the significance of Christ’s Crucifixion as the catalyst for the Second Coming. Keywords: sculpture; art history; archaeology; early medieval; Anglo-Scandinavian; Vikings; iconog- raphy Citation: Doviak, Amanda. 2021. Doorway to Devotion: Recovering the Christian Nature of the Gosforth Cross. -

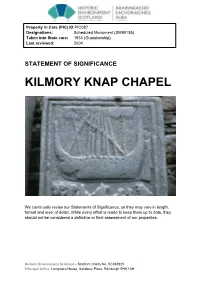

Kilmory Knap Chapel Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC087 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90185) Taken into State care: 1934 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2004 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE KILMORY KNAP CHAPEL We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH KILMORY KNAP CHAPEL BRIEF DESCRIPTION Situated on the western coast of Knapdale, the medieval chapel of Kilmory lies about 4km south of Castle Sween and stands within a walled graveyard that overlooks the Sound of Jura. -

Tewkesbury Borough Housing Monitoring Report

Tewkesbury Borough Housing Monitoring Report 2018/19 AUGUST 2019 Tewkesbury Borough Council Planning Policy Tewkesbury Borough Council Council Offices Gloucester Road Tewkesbury Gloucestershire GL20 5TT www.tewkesbury.gov.uk 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................................... 2 LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 5 What is the Housing Monitoring Report? ...................................................................................................... 5 Adopted Plan Context ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Joint Core Strategy ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Tewkesbury Borough Plan to 2011 .............................................................................................................. 6 Emerging Planning Policy – Tewkesbury Borough Plan ..............................................................................