Mistletoes in Colorado Conifers Fact Sheet No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Juniper Woodlands of the Pacific Northwest

Western Juniper Woodlands (of the Pacific Northwest) Science Assessment October 6, 1994 Lee E. Eddleman Professor, Rangeland Resources Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon Patricia M. Miller Assistant Professor Courtesy Rangeland Resources Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon Richard F. Miller Professor, Rangeland Resources Eastern Oregon Agricultural Research Center Burns, Oregon Patricia L. Dysart Graduate Research Assistant Rangeland Resources Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon TABLE OF CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................... i WESTERN JUNIPER (Juniperus occidentalis Hook. ssp. occidentalis) WOODLANDS. ................................................. 1 Introduction ................................................ 1 Current Status.............................................. 2 Distribution of Western Juniper............................ 2 Holocene Changes in Western Juniper Woodlands ................. 4 Introduction ........................................... 4 Prehistoric Expansion of Juniper .......................... 4 Historic Expansion of Juniper ............................. 6 Conclusions .......................................... 9 Biology of Western Juniper.................................... 11 Physiological Ecology of Western Juniper and Associated Species ...................................... 17 Introduction ........................................... 17 Western Juniper — Patterns in Biomass Allocation............ 17 Western Juniper — Allocation Patterns of Carbon and -

"Santalales (Including Mistletoes)"

Santalales (Including Introductory article Mistletoes) Article Contents . Introduction Daniel L Nickrent, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois, USA . Taxonomy and Phylogenetics . Morphology, Life Cycle and Ecology . Biogeography of Mistletoes . Importance of Mistletoes Online posting date: 15th March 2011 Mistletoes are flowering plants in the sandalwood order that produce some of their own sugars via photosynthesis (Santalales) that parasitise tree branches. They evolved to holoparasites that do not photosynthesise. Holopar- five separate times in the order and are today represented asites are thus totally dependent on their host plant for by 88 genera and nearly 1600 species. Loranthaceae nutrients. Up until recently, all members of Santalales were considered hemiparasites. Molecular phylogenetic ana- (c. 1000 species) and Viscaceae (550 species) have the lyses have shown that the holoparasite family Balano- highest species diversity. In South America Misodendrum phoraceae is part of this order (Nickrent et al., 2005; (a parasite of Nothofagus) is the first to have evolved Barkman et al., 2007), however, its relationship to other the mistletoe habit ca. 80 million years ago. The family families is yet to be determined. See also: Nutrient Amphorogynaceae is of interest because some of its Acquisition, Assimilation and Utilization; Parasitism: the members are transitional between root and stem para- Variety of Parasites sites. Many mistletoes have developed mutualistic rela- The sandalwood order is of interest from the standpoint tionships with birds that act as both pollinators and seed of the evolution of parasitism because three early diverging dispersers. Although some mistletoes are serious patho- families (comprising 12 genera and 58 species) are auto- gens of forest and commercial trees (e.g. -

Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions

Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions Circular 1321 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Photograph taken by Richard F. Miller. Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions By R.F. Miller, Oregon State University, J.D. Bates, T.J. Svejcar, F.B. Pierson, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and L.E. Eddleman, Oregon State University This is contribution number 01 of the Sagebrush Steppe Treatment Evaluation Project (SageSTEP), supported by funds from the U.S. Joint Fire Science Program. Partial support for this guide was provided by U.S. Geological Survey Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center. Circular 1321 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2007 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials con- tained within this report. Suggested citation: Miller, R.F., Bates, J.D., Svejcar, T.J., Pierson, F.B., and Eddleman, L.E., 2007, Western Juniper Field Guide: Asking the Right Questions to Select Appropriate Management Actions: U.S. -

Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes

Ornamental Horticulture Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes Bob Cain, Extension Forest Entomologist One-Seed Juniper (Juniperus monosperma) Description: One-seed juniper grows 20-30 feet high and is multistemmed. Its leaves are scalelike with finely toothed margins. One-seed cones are 1/4-1/2 inch long berrylike structures with a reddish brown to bluish hue. The cones or “berries” mature in one year and occur only on female trees. Male trees produce Alligator Juniper (Juniperus deppeana) pollen and appear brown in the late winter and spring compared to female trees. Description: The alligator juniper can grow up to 65 feet tall, and may grow to 5 feet in diameter. It resembles the one-seed juniper with its 1/4-1/2 inch long, berrylike structures and typical juniper foliage. Its most distinguishing feature is its bark, which is divided into squares that resemble alligator skin. Other Characteristics: • Ranges throughout the semiarid regions of the southern two-thirds of New Mexico, southeastern and central Arizona, and south into Mexico. Other Characteristics: • An American Forestry Association Champion • Scattered distribution through the southern recently burned in Tonto National Forest, Arizona. Rockies (mostly Arizona and New Mexico) It was 29 feet 7 inches in circumference, 57 feet • Usually a bushy appearance tall, and had a 57-foot crown. • Likes semiarid, rocky slopes • If cut down, this juniper can sprout from the stump. Uses: Uses: • Birds use the berries of the one-seed juniper as a • Alligator juniper is valuable to wildlife, but has source of winter food, while wildlife browse its only localized commercial value. -

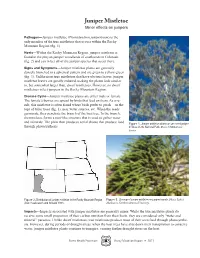

Juniper Mistletoe Minor Effects on Junipers

Juniper Mistletoe Minor effects on junipers Pathogen—Juniper mistletoe (Phoradendron juniperinum) is the only member of the true mistletoes that occurs within the Rocky Mountain Region (fig. 1). Hosts—Within the Rocky Mountain Region, juniper mistletoe is found in the pinyon-juniper woodlands of southwestern Colorado (fig. 2) and can infect all of the juniper species that occur there. Signs and Symptoms—Juniper mistletoe plants are generally densely branched in a spherical pattern and are green to yellow-green (fig. 3). Unlike most true mistletoes that have obvious leaves, juniper mistletoe leaves are greatly reduced, making the plants look similar to, but somewhat larger than, dwarf mistletoes. However, no dwarf mistletoes infect junipers in the Rocky Mountain Region. Disease Cycle—Juniper mistletoe plants are either male or female. The female’s berries are spread by birds that feed on them. As a re- sult, this mistletoe is often found where birds prefer to perch—on the tops of taller trees (fig. 1), near water sources, etc. When the seeds germinate, they penetrate the branch of the host tree. In the branch, the mistletoe forms a root-like structure that is used to gather water and minerals. The plant then produces aerial shoots that produce food Figure 1. Juniper mistletoe plants on one-seed juniper through photosynthesis. in Mesa Verde National Park. Photo: USDA Forest Service. Figure 2. Distribution of juniper mistletoe in the Rocky Mountain Region Figure 3. Closeup of juniper mistletoe on juniper branch. Photo: Robert (from Hawksworth and Scharpf 1981). Mathiasen, Northern Arizona University. Impacts—Impacts associated with juniper mistletoe are generally minor. -

Wakefield 306 2Nd 79500 307 2Nd 71300

WAKEFIELD 306 2ND 79500 307 2ND 71300 405 2ND 56100 406 2ND 81000 409 2ND 8110 508 2ND 124000 302 3RD 83920 303 3RD 131700 304 3RD 112500 305 3RD 25000 306 3RD 139000 307 3RD 56700 308 3RD 58000 403 3RD 10870 405 3RD 35700 501 3RD 144200 503 3RD 17120 704 3RD 33780 804 3RD 920 902 3RD 47800 1600 3RD 15410 1706 3RD 22050 1708 3RD 113870 301 4TH 166700 303 4TH 46400 305 4TH 74900 306 4TH 130300 307 4TH 120300 402 4TH 121900 404 4TH 125800 602 4TH 78100 606 4TH 132500 701 4TH 174540 706 4TH 227000 305 5TH 20500 308 5TH 100970 312 5TH 150800 102 6TH 117950 104 6TH 57100 106 6TH 84360 204 6TH 89200 206 6TH 38200 208 6TH 73900 304 6TH 18490 305 6TH 77130 401 6TH 148000 403 6TH 31750 607 6TH 106500 701 6TH 162000 703 6TH 178500 705 6TH 173300 805 6TH 131900 102 7TH 145000 103 7TH 151500 104 7TH 186800 107 7TH 141500 201 7TH 121200 202 7TH 138300 203 7TH 168900 204 7TH 118800 206 7TH 125500 303 7TH 50600 404 7TH 18170 602 8TH 123100 802 8TH 98700 803 8TH 181400 804 8TH 104900 903 8TH 6080 905 8TH 6080 1001 8TH 6090 1003 8TH 183100 1005 8TH 176700 1007 8TH 167800 1101 8TH 225800 702 9TH 187200 704 9TH 240500 804 9TH 101600 603 10TH 10810 604 10TH 242900 706 10TH 44810 802 10TH 41110 901 10TH 130900 902 10TH 265000 902 10TH 13530 904 10TH 674320 905 10TH 80040 402 BIRCH 79800 403 BIRCH 148900 404 BIRCH 90000 405 BIRCH 107900 406 BIRCH 116100 502 BIRCH 200800 503 BIRCH 145500 504 BIRCH 63000 505 BIRCH 110600 506 BIRCH 216300 602 BIRCH 167600 603 BIRCH 160500 604 BIRCH 96000 605 BIRCH 151100 605 BIRCH 16180 606 BIRCH 6500 607 BIRCH 109300 608 BIRCH -

The World Needs Network Innovation. Juniper Is Here to Help

The world needs network innovation. Juniper is here to help. In a world where the pace of change is accelerating at an unprecedented rate the network has taken on a new level of importance as the vehicle for pulling together our best people, best thinking, and best hope for addressing the critical challenges we face as a global community. The JUNIPER BY THE macro-trends of cloud computing and the mobile Internet NUMBERS hold the potential to expand the reach and power of the network—while creating an explosion of new subscribers, • The world’s top five social media properties new traffic, and new content. In the face of such intense are supported by Juniper demand, this potential cannot be realized with legacy Networks. thinking. Juniper Networks stands as a response and a • The top 10 telecom companies challenge to the traditional approach to the network. in the world run on Juniper Networks. • Juniper Networks is deployed in more than 1,400 national Our Vision government organizations We believe the network is the single greatest vehicle for knowledge, collaboration, and around the world. human advancement that the world has ever known. Now more than ever, the world relies on high-performance networks. And now more than ever, the world needs network • Juniper has over 8,700 innovation to unleash our full potential. employees in 46 worldwide offices, serving over 100 The network plays a central role in addressing the critical challenges we face as a global countries. community. Consider the healthcare industry, where the network is the foundation for new models of mobile affordable care for underserved communities. -

Mistletoes: Pathogens, Keystone Resource, and Medicinal Wonder Abstracts

Mistletoes: Pathogens, Keystone Resource, and Medicinal Wonder Abstracts Oral Presentations Phylogenetic relationships in Phoradendron (Viscaceae) Vanessa Ashworth, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden Keywords: Phoradendron, Systematics, Phylogenetics Phoradendron Nutt. is a genus of New World mistletoes comprising ca. 240 species distributed from the USA to Argentina and including the Antillean islands. Taxonomic treatments based on morphology have been hampered by phenotypic plasticity, size reduction of floral parts, and a shortage of taxonomically useful traits. Morphological characters used to differentiate species include the arrangement of flowers on an inflorescence segment (seriation) and the presence/absence and pattern of insertion of cataphylls on the stem. The only trait distinguishing Phoradendron from Dendrophthora Eichler, another New World mistletoe genus with a tropical distribution contained entirely within that of Phoradendron, is the number of anther locules. However, several lines of evidence suggest that neither Phoradendron nor Dendrophthora is monophyletic, although together they form the strongly supported monophyletic tribe Phoradendreae of nearly 360 species. To date, efforts to delineate supraspecific assemblages have been largely unsuccessful, and the only attempt to apply molecular sequence data dates back 16 years. Insights gleaned from that study, which used the ITS region and two partitions of the 26S nuclear rDNA, will be discussed, and new information pertinent to the systematics and biology of Phoradendron will be reviewed. The Viscaceae, why so successful? Clyde Calvin, University of California, Berkeley Carol A. Wilson, The University and Jepson Herbaria, University of California, Berkeley Keywords: Endophytic system, Epicortical roots, Epiparasite Mistletoe is the term used to describe aerial-branch parasites belonging to the order Santalales. -

Conspecific Pollen on Insects Visiting Female Flowers of Phoradendron Juniperinum (Viscaceae) in Western Arizona

Western North American Naturalist Volume 77 Number 4 Article 7 1-16-2017 Conspecific pollen on insects visiting emalef flowers of Phoradendron juniperinum (Viscaceae) in western Arizona William D. Wiesenborn [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Recommended Citation Wiesenborn, William D. (2017) "Conspecific pollen on insects visiting emalef flowers of Phoradendron juniperinum (Viscaceae) in western Arizona," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 77 : No. 4 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol77/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 77(4), © 2017, pp. 478–486 CONSPECIFIC POLLEN ON INSECTS VISITING FEMALE FLOWERS OF PHORADENDRON JUNIPERINUM (VISCACEAE) IN WESTERN ARIZONA William D. Wiesenborn1 ABSTRACT.—Phoradendron juniperinum (Viscaceae) is a dioecious, parasitic plant of juniper trees ( Juniperus [Cupressaceae]) that occurs from eastern California to New Mexico and into northern Mexico. The species produces minute, spherical flowers during early summer. Dioecious flowering requires pollinating insects to carry pollen from male to female plants. I investigated the pollination of P. juniperinum parasitizing Juniperus osteosperma trees in the Cerbat Mountains in western Arizona during June–July 2016. I examined pollen from male flowers, aspirated insects from female flowers, counted conspecific pollen grains on insects, and estimated floral constancy from proportions of conspecific pollen in pollen loads. -

Epiparasitism in Phoradendron Durangense and P. Falcatum (Viscaceae) Clyde L

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 27 | Issue 1 Article 2 2009 Epiparasitism in Phoradendron durangense and P. falcatum (Viscaceae) Clyde L. Calvin Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, California Carol A. Wilson Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, California Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Calvin, Clyde L. and Wilson, Carol A. (2009) "Epiparasitism in Phoradendron durangense and P. falcatum (Viscaceae)," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 27: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol27/iss1/2 Aliso, 27, pp. 1–12 ’ 2009, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden EPIPARASITISM IN PHORADENDRON DURANGENSE AND P. FALCATUM (VISCACEAE) CLYDE L. CALVIN1 AND CAROL A. WILSON1,2 1Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, California 91711-3157, USA 2Corresponding author ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Phoradendron, the largest mistletoe genus in the New World, extends from temperate North America to temperate South America. Most species are parasitic on terrestrial hosts, but a few occur only, or primarily, on other species of Phoradendron. We examined relationships among two obligate epiparasites, P. durangense and P. falcatum, and their parasitic hosts. Fruit and seed of both epiparasites were small compared to those of their parasitic hosts. Seed of epiparasites was established on parasitic-host stems, leaves, and inflorescences. Shoots developed from the plumular region or from buds on the holdfast or subjacent tissue. The developing endophytic system initially consisted of multiple separate strands that widened, merged, and often entirely displaced its parasitic host from the cambial cylinder. -

Radial Growth Rate Responses of Western Juniper (Juniperus Occidentalis Hook.) to Atmospheric and Climatic Changes: a Longitudinal Study from Central Oregon, USA

Article Radial Growth Rate Responses of Western Juniper (Juniperus occidentalis Hook.) to Atmospheric and Climatic Changes: A Longitudinal Study from Central Oregon, USA Peter T. Soulé 1,* and Paul A. Knapp 2 1 Appalachian Tree-Ring Laboratory, Department of Geography and Planning, Appalachian State University, Boone, NC 28608, USA 2 Carolina Tree-Ring Science Laboratory, Department of Geography, Environment, and Sustainability, University of North Carolina-Greensboro, Greensboro, NC 27412, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 19 September 2019; Accepted: 6 December 2019; Published: 10 December 2019 Abstract: Research Highlights: In this longitudinal study, we explore the impacts of changing atmospheric composition and increasing aridity on the radial growth rates of western juniper (WJ; Juniperus occidentalis Hook). Since we sampled from study locations with minimal human agency, we can partially control for confounding influences on radial growth (e.g., grazing and logging) and better isolate the relationships between radial growth and climatic conditions. Background and Objectives: Our primary objective is to determine if carbon dioxide (CO2) enrichment continues to be a primary driving force for a tree species positively affected by increasing CO2 levels circa the late 1990s. Materials and Methods: We collected data from mature WJ trees on four minimally disturbed study sites in central Oregon and compared standardized radial growth rates to climatic conditions from 1905–2017 using correlation, moving-interval correlation, and regression techniques. Results: We found the primary climate driver of radial growth for WJ is antecedent moisture over a period of several months prior to and including the current growing season. Further, the moving-interval correlations revealed that these relationships are highly stable through time. -

Estimation of Strength Loss and Decay Severity of Juniperus Procera by Juniper Pocket Rots Fungus, P. Demidoffii in Ethiopian Forests

Regular Article pISSN: 2288-9744, eISSN: 2288-9752 J F E S Journal of Forest and Environmental Science Journal of Forest and Vol. 36, No. 2, pp. 143-155, June, 2020 Environmental Science https://doi.org/10.7747/JFES.2020.36.2.143 Estimation of Strength Loss and Decay Severity of Juniperus procera by Juniper Pocket Rots Fungus, P. demidoffii in Ethiopian Forests Addisu Assefa* Department of Biology, Madda Walabu University, Bale Robe 247, Ethiopia Abstract A juniper pocket rot fungus, Pyrofomes demidoffii is a basidiomycetous fungus responsible for damage of living Juniperus spp. However, its effect on the residual strength and on the extent of decay of juniper’s trunk was not determined in any prior studies. The purpose of this study was to study the features of J. procera infected by P. demdoffii, and to estimate the level of strength loss and decay severity in the trunk at D.B.H height using different five formulas. Infected juniper stands were examined in two Ethiopian forests through Visual Tree Assessment (VTA) followed by a slight destructive drilling of the trunk at D.B.H height. The decayed juniper tree is characterized by partially degraded lignin material at incipient stage of decay to completely degraded lignin material at final stage of decay. In the evaluated formulas, results of ANOVA showed that a significantly higher mean percentage of strength loss and decay severity were recorded in the trees of larger D.B.H categories (p<0.001). The strength loss formulas produced the same to similar patterns of sum of ranks of strength loss or decay severity in the trunk, but the differences varied significantly among D.B.H categories in Kruskal Wallis-test (p<0.001).