2009 Twin Cities Transit System Performance Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Annual Regional Park-And-Ride System

2019 ANNUAL REGIONAL PARK & RIDE SYSTEM REPORT JANUARY 2020 Prepared for: Metropolitan Council Metro Transit Minnesota Valley Transit Authority SouthWest Transit Maple Grove Transit Plymouth Metrolink Northstar Link Minnesota Department of Transportation Prepared by: Ari Del Rosario Metro Transit Engineering and Facilities, Planning and Urban Design Table of Contents Overview ......................................................................................................................................................3 Capacity Changes........................................................................................................................................6 System Capacity and Usage by Travel Corridor .........................................................................................7 Planned Capacity Expansion .......................................................................................................................8 About the System Survey ............................................................................................................................9 Appendix A: Facility Utilization Data .......................................................................................................10 Park & Ride System Data .....................................................................................................................10 Park & Pool System Data .....................................................................................................................14 Bike & Ride -

Winter 2016 Edition Join MPTA at Transportation Day at the Capitol

Winter 2016 Edition Join MPTA at Transportation Day at the Capitol 2016! Don’t miss your chance to be heard on transportation issues and funding needs by state legislators! MPTA staff is available to arrange appointments. March 16, 2016 from 8:30 AM - 2:30 PM Regional Council of Carpenters - Great Hall 710 Olive Street, St. Paul, Minnesota 55130 Registration is Only $35 for MPTA Members! Register Today President’s Column Craig Rempp What does the future of transit look like? More and more we seem to be confronted by the prospect of a new future that is coming quickly. More transit systems are merging together and offering new ways for people to get around. New services will be available to people soon such as rides provided by Uber or Uber Assist or Lyft. New funding has been approved at the federal level and local options or new funding partnerships may be happening in the very near future. All of these trends will change how we think about mobility and how we provide public transit service. The Minnesota Public Transit Association will be working to help you track all the changes and to assist our member systems as we navigate a new future. MnDOT’s Office of Transit continues to work on updating the Greater Minnesota Transit Investment Plan, the 20-year vision for transit in Greater Minnesota. As we think about the future, it’s critical for all of us to provide feedback on the Transit Investment Plan including information on what is needed in our communities. We can’t predict the future, but we can put some ballpark numbers around unmet needs for transit service in the immediate future. -

Transportation Resources

763-424-0845 MN Relay: 1800 818-0395 Your On Campus Connection to Resources in the Community”. Transportation Resources North Hennepin Community College Community Connections does not assume responsibility for the quality of services provided by outside agencies or websites listed above. Inclusion on the list does not imply endorsement nor does omission indicate disap- proval. This information can be made available in alternate formats by contacting the Access Services Office at 763-493-0555 or by TTY at 763-493-0558 HELPFUL RESOURCES MAPLEGROVE DIAL A RIDE PLYMOUTH METROLINK DIAL-A-RIDE LYFT https://www.maplegrovemn.gov/services/ 763-559-5057 M-F 6am to 6pm LYFT.com transit/dial-a-ride/ http://www.plymouthmn.gov/departments/ Sign-Up online for a new and faster way to get The Dial-a-Ride program is an advance reserva- administrative-services-/transit/plymouth- around, then upload app to your smartphone. tion, shared-ride, curb-to-curb van service availa- metrolink-dial-a-ride Price can vary depending on time of day, how ble to the general public. many in a vehicle and distance. You can sched- Dial-A-Ride $3 each way Service Area: Within City of Maple Grove bounda- ule up to 7 days in advance. ries, plus service to City of Osseo, Hennepin Tech- Rides may be reserved up to 5days in ad- vance nical College/North Hennepin Community College UBER and Starlight Transit Station (next to Cub Foods in Serves Plymouth and surroundings areas Uber.com Brooklyn Park) Fares: $1.75 cash per one way ride Sign-Up online for a new (exact change, no checks) METRO TRANSIT—TWINS CITIES and faster way to get 612-373-3333 around, then upload app to METRO MOBILITY www.metrotransit.org your smartphone. -

Initial Transit Agency Outreach Summary

Memorandum SRF No. 12758 To: Cole Hiniker, AICP Metropolitan Council From: Joseph Kapper, AICP SRF Consulting Group Date: May 20, 2020 Subject: Metropolitan Council Service Allocation Study Initial Transit Agency Outreach Summary Executive Summary Introduction One of the first tasks associated with the Service Allocation Study involved a report on existing conditions for transit service within the Minneapolis – St. Paul region. In addition to documenting the scope of transit service and socioeconomic data, the consultant team conducted outreach to each transit provider to understand the scope of their services and gain general input on the study. In March and April of 2020 several video and tele-conferences were held with individuals responsible for service monitoring, planning, and allocation at each agency. The content of each meeting included the following topics: • Offering an overview of the Service Allocation Study and gathering initial feedback on work to date and potential successful outcomes. • Transit agencies provide a summary of their current services. • How are transit operating resources allocated today? o How does the agency currently approach service allocation decisions? o What policies currently exist to guide service expansion or reduction? o Are there separate performance guidelines or goals for different types of service? • Agency planning and service development priorities. As of this memo’s completion, interviews have been conducted with Metro Transit, Minnesota Valley Transit Authority, SouthWest Transit, the City of Plymouth, Maple Grove Transit, and Metropolitan Transportation Services. Prior to each stakeholder interview, the consultant team reviewed the transit services currently offered by each agency, as well as relevant survey results, internal procedures, and long-range planning documents provided for the purposes of this study. -

Central Corridor Supplemental DEIS Chapter 9: Indirect and Cumulative

Central Corridor LRT Project Chapter 9 Indirect and Cumulative Impacts 9.0 INDIRECT AND CUMULATIVE IMPACTS This chapter identifies the potential indirect and cumulative impacts that could occur with implementation of the Central Corridor LRT Project. Section 9.1 introduces the concepts of indirect and cumulative impacts, and how and why the analysis is done. Section 9.2 presents the methods used to decide what data was needed, how it was collected, and how it was analyzed. This section also describes some general trends in the study area and provides a table of the significant and reasonably foreseeable future projects in the study area. Finally, this section demonstrates how each topic was selected according to its potential for indirect and cumulative impacts. Section 9.3 presents a discussion of potential indirect impacts for each topic and a discussion of cumulative impacts. Section 9.4 summarizes the potential indirect and cumulative effects of the AA/DEIS LPA and the Key Project Elements and lists available mitigation measures that could be applied where indirect and cumulative impacts may occur. 9.1 Introduction The Central Corridor Alternatives Analysis and Draft Environmental Impact Statement (AA/DEIS) did not include a separate section for an indirect and cumulative effects analysis (ICEA). This section, therefore, is intended to provide a basic discussion of ICEA and to describe the potential for indirect effects and cumulative impacts from the AA/DEIS Locally Preferred Alternative (AA/DEIS LPA), as well as to the Key Project Elements, in combination with other past, present, and future actions. For this chapter, the AA/DEIS LPA and the Key Project Elements are referred to as the Central Corridor LRT project. -

Minneapolis Transportation Action Plan (Engagement Phase 3)

Minneapolis Transportation Action Plan (Engagement Phase 3) Email Comment Topic Comment # The recommendations in this submission expand on this principle and support the overall Transportation Action Plan goals of designing transportation to achieve the aims of Minneapolis 2040, address climate change, reduce traffic fatalities and injuries, and improve racial and economic equity. In line with these goals, our most significant recommendations for the Prospect Park area are to • Invest in the protected bike network: extending the Greenway over the River, and building the Prospect Park Trail along railroad right-of- way • Transform University Avenue and Washington Avenues • Complete the Grand Rounds and use the Granary corridor to redirect truck traffic Priorities for transportation improvements in Prospect Park 1. Improve pedestrian infrastructure throughout the community including safe crossings of University Avenue SE (Bedford, Malcolm, 29th and 27th), Franklin Avenue SE (Bedford, Seymour) and 27th Avenue SE (Essex, Luxton Park to Huron pedestrian overpass). We encourage the city to narrow residential intersections, particularly in Bicycling, the Tower Hill sub-neighborhood where streets do not meet at right Walking, 1 angles, and crossing distances are significantly longer than needed. Additional Planters and plastic delineators could be used to achieve this ahead of Comments reconstruction. Maintenance and improvements should focus on public safety, adequate lighting and landscape upkeep. Throughout the neighborhood residents have cited safety (particularly at night), sidewalk disrepair, narrowness, snow and ice issues, and have expressed support for full ADA compliance. 2. Complete the Minneapolis Grand Rounds and the Granary Corridor (see Map 2) to enhance community access to city and regional parks and trails as well as to adjoining neighborhoods. -

2008 Transportation Improvement Program for the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area

2006 - 2008 TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM FOR THE TWIN CITIES METROPOLITAN AREA September 14, 2005 Mears Park Centre, 230 East Fifth Street, St. Paul, Minnesota 55101 Metropolitan Council Members Peter Bell Chair Roger Scherer District 1 Tony Pistilli District 2 Mary Hill Smith District 3 Julius C. Smith District 4 Russ Susag District 5 Peggy Leppik District 6 Annette Meeks District 7 Lynette Wittsack District 8 Natalie Haas Steffen District 9 Vacant District 10 Georgeanne Hilker District 11 Chris Georgacas District 12 Rick Aguilar District 13 Song Lo Fawcett District 14 Daniel Wolter District 15 Brian McDaniel District 16 General phone 651 602-1000 Data Center 651-602-1140 TTY 651 291-0904 Metro Info Line 651 602-1888 E-mail [email protected] Web site www.metrocouncil.org Publication no. 35-05-060 Printed on recycled paper with at least 20% post-consumer waste. On request, this publication will be made available in alternative formats to people with disabilities. Call the Metropolitan Council Data Center at 651 602-1140 or TTY 651 291-0904. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page SUMMARY .....................................................................................................................................1 1. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................2 Federal Requirements.......................................................................................................................2 Regional Planning Process ...............................................................................................................4 -

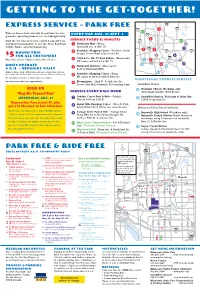

Getting to the Get-Together! ★

GETTING TO THE GET-TOGETHER! ★ EXPRESS SERVICE – PARK FREE 35W 1 35E 94 10 Express buses travel directly to and from the fair- EVERY DAY AUG. 21-SEPT. 1 694 grounds, operating from 8 a.m. to midnight daily. SERVICE EVERY 15 MINUTES 2 Find the lot closest to you: call 612-341-4287 for 494 11 automated information or use the State Fair Park 1 Northtown Mall – Blaine 694 & Ride Finder at metrotransit.org. University Ave. & Hwy. 10 7 Brookdale Shopping Center 3 394 4 ROUND-TRIP 2 – Brooklyn Center 94 94 $ Shingle Creek Pkwy. & Bass Lake Rd. 5 FOR ALL CUSTOMERS 35W 8 I-394 & Co. Rd. 73 Park & Ride 35E Exact fare, please. Children under five ride free. 3 – Minnetonka 12 5 SW corner of I-394 & Co. Rd. 73 494 BUSES OPERATE 13 494 6 9 4 Dunwoody Institute – Minneapolis 15 8 A.M. – MIDNIGHT DAILY I-394 & Dunwoody Blvd. Express buses drop off/pick up customers at fair Gate #20 (on 14 Southdale Shopping Center the south side of Como Ave. across from the Warner Coliseum). 5 – Edina NE corner of lot near 66th & York Ave. All express service is wheelchair accessible. ADDITIONAL EXPRESS SERVICE Bus departure times are approximate. 6 Bloomington – 82nd St. & 24th Ave. So. Across from Mall of America East parking ramp SouthWest Transit RIDE ON Wooddale Church, Weekdays only SERVICE EVERY HALF HOUR 12 “Hop On Transit Day” 6630 Shady Oak Rd., Eden Prairie Oakdale Center Park & Ride WEDNESDAY, AUG. 27 7 – Oakdale 13 SouthWest Station, Weekends & Labor Day West of I-694 on 10th St. -

Westgate Business Center I Under New Ownership!

OFFICE/WAREHOUSE SPACE FOR LEASE > Westgate Business Center I 2561 - 2631 Territorial Road | St. Paul, MN 55114 Untitled map Untitled layer Under New Ownership!1045 Westgate Dr BUILDING AMENITIES > High-image office/warehouse space > 18’ clear height SITE > 78,945 SF office/warehouse building > Close proximity to public transportation; just two short blocks from the Green Line LRT (Westgate Station) and Metro Transit bus routes along University Avenue > Excellent access to I-94 / I-35W and Highway 280 > Located in high-image Westgate Business Park > Space available immediately CONTACT US > Owned by: ERIC BATIZA SIOR STEVE NILSSON CCIM SIOR MATT NEWELL 952 837 3007 952 897 7899 651 356 5074 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Colliers International | Minneapolis-St. Paul | 901 South Marquette Avenue, Suite 300, Minneapolis, MN 55402 | colliers.com/msp WESTGATE BUSINESS CENTER I > FOR LEASE TCF Bank Stadium 67,000 vpd Hwy 280 15,100 vpd University Ave SE Westgate Station Light Rail Stop Mississippi River BUILDING HIGHLIGHTS PROPERTY ADDRESS: 2020 EST CAM & REAL ESTATE AVAILABLE: 2561-2631 Territorial Road TAX: Suite 2609-A (2631 Territorial Rd) St. Paul, MN 55114 $2.64 PSF Tax 2,417 sf office $2.33 PSF CAM 3,572 sf warehouse BUILDING SQUARE FEET: $4.97 PSF TOTAL 5,989 sf total 78,945 SF Total ➤ NET LEASE RATES: LOADING: N ImageImage LandsatLandsat // CopernicusCopernicus YEAR BUILT: Negotiable One (1) dock door 1991 One (1) grade-level drive-in door Image Landsat / Copernicus CLEAR HEIGHT: PARKING: 18’ 232 surface spaces (2.94/1,000 SF) Colliers International | Minneapolis-St. -

Draft 1:Layout 1.Qxd

Results: Future Needs MVTA EBG Expansion 2013 Space for 40 buses $10 Million Buses 2013-17 52 Replacement $39.8 Million Buses 2013-17 10 Expansion Vehicles $ 4.6 Million SouthWest Transit Buses 2012-14 5 Expansion Buses $ 2.9 Million The Suburban Transit Association (STA) was founded in 1995 and brings to- 169 Park & Ride (phase I) 2013-15 250 stalls/shelter $ 3.2 Million Garage Preservation 2013-15 PM and Upgrades $ 3.1 Million gether 12 suburban communities in the Twin Cities Metropolitan area that elected not Buses 2013-15 12 Replacement Buses $ 4.2 Million to be part of the traditional transit system. Plymouth Park & Ride 2014-16 250 spaces $15 Million The purpose of STA is to jointly and cooperatively develop programs of mutual in- Northwest Metro Garage 2015-16 Storage for 100 buses $25 Million terest that would benefit the citizens of the communities served. These transit systems Maple Grove Parkway Transit Station 2013 Construct 298-stall ramp $ 3 Million (also referred to as Suburban Transit Providers) provide flexible transit services through Buses 2013-17 22 buses (5-40’, 11 artics, 1 shuttle, 5 DAR) $11.6 Million a variety of programs, including: flex routes, reverse commute services, local service be- BlueXpress (Shakopee/Prior Lake) tween communities and/or regional transit centers, dial-a-ride services and elderly/dis- Marschall Rd Transit Station 2013 400 spaces $ 3.4 Million Buses 2013 3 Expansion Buses $ 1.5 Million abled transportation services. Results: Recent Projects The primary product of the systems, however, is peak-period express bus service. -

2013 Count Report

Bike Walk Twin Cities 2013 Count Report Issued December 12, 2013 a program of transit for livable communities Executive Summary This annual report, the 2013 Bike Walk Twin Cities Pedestrian and Bicycle Count Report, provides a detailed view of bicycling and walking at benchmark locations across the Twin Cities. This ongoing to develop a more complete picture of overall travel behavior in our communities. collection of annual data about nonmotorized traffic supplements existing data on motorized traffic key findings 1. Rates of bicycling and walking Annual counts at 43 benchmark locations in the Twin Cities metro indicate that bicycling increased 78 percent and walking 16 percent between 2007 and 2013. Overall, active transportation (bicycling and walking together) rose by 45 percent from 2007 to 2013. Between 2012 and 2013, bicycling increased 13 percent, walking decreased 6 percent, and active transportation increased 4 at locations encompassing a broad range of street types and facilities and representing all areas ofpercent. Minneapolis The findings and several are based adjacent on manual communities. 2-hour Thecounts 2013 conducted counts are by thespecially-trained highest ever recorded volunteers for bicycle trips, and the second highest ever recorded for pedestrian trips (down slightly from the record high of 2012). Bike Walk Twin Cities | A Program of Transit for Livable Communities | 2013 Count Report | December 2013 | Page 1 2. Impact of new facilities 2013 key findings Count locations with new facilities (new bike lanes summary* or other improvements) showed higher increases in bicycling than locations without improvements. Trails 2007-2013 connections saw the greatest increases in bicycle where extensions were built to improve network Bicyclists: +78% to facilities improvements and more related to major destinations.use. -

Nice Ride Minnesota Program Evaluation

NICE RIDE MINNESOTA PROGRAM EVALUATION Minneapolis-St. Paul Bike Share System Prepared by: Jessica Schoner1 Greg Lindsey2 David Levinson1 1Department of Civil, Environmental, and Geo- Engineering 2Humphrey School of Public Affairs University of Minnesota Submitted to: CENTER FOR PREVENTION AT BLUE CROSS AND BLUE SHIELD OF MINNESOTA NICE RIDE MINNESOTA May 2015 Contents 1 Introduction1 1.1 Minneapolis-St. Paul Bike Share System Study Objectives.............1 1.2 Study Purpose and Goals...............................1 1.3 Structure of Report..................................1 2 Approach and Methods3 2.1 Analysis of Nice Ride electronic trip and member records..............3 2.2 Survey of Nice Ride members............................3 2.3 Secondary analyses of related databases (Census, TBI, etc.).............4 3 Effects on individual physical activity7 4 Effects on rates of cycling within general population 11 4.1 Spillover effects on non-member cycling....................... 11 4.2 Diffusion effects on expanding membership..................... 14 5 Effects on broader culture of active living 17 Appendices A IRB A-1 B Minneapolis Survey Instrument B-1 B.1 Survey......................................... B-1 B.2 Recruiting email.................................... B-24 C Minneapolis Survey Data Report C-1 D Preliminary Minneapolis Survey Findings D-1 E Bike Walk Twin Cities 2013 Count Report E-1 F Minneapolis Supplemental Models F-1 F.1 Supplemental Innovation Diffusion/Membership Descriptive Statistics....... F-1 F.2 Supplemental Innovation