A Life Inspired by an Unexpected Genius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:1906.07410V4 [Math.NT] 29 Sep 2020 Ainlpwrof Power Rational Ftetidodrmc Ht Function Theta Mock Applications](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9806/arxiv-1906-07410v4-math-nt-29-sep-2020-ainlpwrof-power-rational-ftetidodrmc-ht-function-theta-mock-applications-459806.webp)

Arxiv:1906.07410V4 [Math.NT] 29 Sep 2020 Ainlpwrof Power Rational Ftetidodrmc Ht Function Theta Mock Applications

MOCK MODULAR EISENSTEIN SERIES WITH NEBENTYPUS MICHAEL H. MERTENS, KEN ONO, AND LARRY ROLEN In celebration of Bruce Berndt’s 80th birthday Abstract. By the theory of Eisenstein series, generating functions of various divisor functions arise as modular forms. It is natural to ask whether further divisor functions arise systematically in the theory of mock modular forms. We establish, using the method of Zagier and Zwegers on holomorphic projection, that this is indeed the case for certain (twisted) “small divisors” summatory functions sm σψ (n). More precisely, in terms of the weight 2 quasimodular Eisenstein series E2(τ) and a generic Shimura theta function θψ(τ), we show that there is a constant αψ for which ∞ E + · E2(τ) 1 sm n ψ (τ) := αψ + X σψ (n)q θψ(τ) θψ(τ) n=1 is a half integral weight (polar) mock modular form. These include generating functions for combinato- rial objects such as the Andrews spt-function and the “consecutive parts” partition function. Finally, in analogy with Serre’s result that the weight 2 Eisenstein series is a p-adic modular form, we show that these forms possess canonical congruences with modular forms. 1. Introduction and statement of results In the theory of mock theta functions and its applications to combinatorics as developed by Andrews, Hickerson, Watson, and many others, various formulas for q-series representations have played an important role. For instance, the generating function R(ζ; q) for partitions organized by their ranks is given by: n n n2 n (3 +1) m n q 1 ζ ( 1) q 2 R(ζ; q) := N(m,n)ζ q = −1 = − − n , (ζq; q)n(ζ q; q)n (q; q)∞ 1 ζq n≥0 n≥0 n∈Z − mX∈Z X X where N(m,n) is the number of partitions of n of rank m and (a; q) := n−1(1 aqj) is the usual n j=0 − q-Pochhammer symbol. -

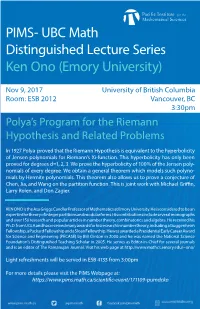

UBC Math Distinguished Lecture Series Ken Ono (Emory University)

PIMS- UBC Math Distinguished Lecture Series Ken Ono (Emory University) Nov 9, 2017 University of British Columbia Room: ESB 2012 Vancouver, BC 3:30pm Polya’s Program for the Riemann Hypothesis and Related Problems In 1927 Polya proved that the Riemann Hypothesis is equivalent to the hyperbolicity of Jensen polynomials for Riemann’s Xi-function. This hyperbolicity has only been proved for degrees d=1, 2, 3. We prove the hyperbolicity of 100% of the Jensen poly- nomials of every degree. We obtain a general theorem which models such polyno- mials by Hermite polynomials. This theorem also allows us to prove a conjecture of Chen, Jia, and Wang on the partition function. This is joint work with Michael Griffin, Larry Rolen, and Don Zagier. KEN ONO is the Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Mathematics at Emory University. He is considered to be an expert in the theory of integer partitions and modular forms. His contributions include several monographs and over 150 research and popular articles in number theory, combinatorics and algebra. He received his Ph.D. from UCLA and has received many awards for his research in number theory, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Packard Fellowship and a Sloan Fellowship. He was awarded a Presidential Early Career Award for Science and Engineering (PECASE) by Bill Clinton in 2000 and he was named the National Science Foundation’s Distinguished Teaching Scholar in 2005. He serves as Editor-in-Chief for several journals and is an editor of The Ramanujan Journal. Visit his web page at http://www.mathcs.emory.edu/~ono/ Light refreshments will be served in ESB 4133 from 3:00pm For more details please visit the PIMS Webpage at: https://www.pims.math.ca/scientific-event/171109-pumdcko www.pims.math.ca @pimsmath facebook.com/pimsmath . -

Sixth Ramanujan Colloquium

University of Florida, Mathematics Department SIXTH RAMANUJAN* COLLOQUIUM by Professor Ken Ono ** Emory University on Adding and Counting Date and Time: 4:05 - 4:55pm, Monday, March 12, 2012 Room: LIT 109 Refreshments: After Colloquium in the Atrium (LIT 339) Abstract: One easily sees that 4 = 3+1 = 2+2 = 2+1+1 = 1+1+1+1, and so we say there are five partitions of 4. What may come as a surprise is that this simple task leads to very subtle and difficult problems in mathematics. The nature of adding and counting has fascinated many of the world's leading mathematicians: Euler, Ramanujan, Hardy, Rademacher, Dyson, to name a few. And as is typical in number theory, some of the most fundamental (and simple to state) questions have remained open. In 2010, with the support of the American Institute for Mathematics and the National Science Foundation, the speaker assembled an international team of researchers to attack some of these problems. Come hear about their findings: new theories which solve some of the famous old questions. * ABOUT RAMANUJAN: Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887-1920), a self-taught genius from South India, dazzled mathematicians at Cambridge University by communicating bewildering formulae in a series of letters. G. H. Hardy invited Ramanujan to work with him at Cambridge, convinced that Ramanujan was a "Newton of the East"! Ramanujan's work has had a profound and wide impact within and outside mathematics. He is considered one of the greatest mathematicians in history. ** ABOUT THE SPEAKER: Ken Ono is one of the top number theorists in the world and a leading authority in the theory of partitions, modular forms, and the work of the Indian genius Srinivasa Ramanujan. -

Mentoring Graduate Students: Some Personal Thoughts3

Early Career the listeners. Like a toddler. He said he tested this when I am not quite sure how I successfully navigated the he was a PhD student. He wanted to know what “ho- stormy seas that defined my early career in mathematics. lomorphic vector bundle” means. So, he went to the What I do know is that I am now fifty-one years old, and math lounge and repeated those three words over and I have enjoyed a privileged career as a research mathe- over again. Now he is an expert in complex geometry. matician. I have had the pleasure of advising thirty PhD • Waking up to Email. Every mentor has a different style. students, with most assuming postdoctoral positions at So does every mentee. A while back, PhD students at top Group 1 institutions. Furthermore, I am proud of the Berkeley complained that they do not get enough at- fact that mathematics continues to play a central role in tention from their advisors. My students think that they their daily lives. receive too much attention from their advisor. A friend How did I make it? Good question. I do know that I once referred to my style as “the samurai method.” It needed the strong support of mentors who kept me afloat involves a barrage of emails, usually sent between 4am along the way. You might know their names: Paul Sally, and 5am. While this is fine for some, it does not work Basil Gordon, and Andrew Granville. I learned a lot from for others. these teachers, and I hope that I have been able to pass their wisdom on to my students of all ages. -

Harmonic Maass Forms, Mock Modular Forms, and Quantum Modular Forms

HARMONIC MAASS FORMS, MOCK MODULAR FORMS, AND QUANTUM MODULAR FORMS KEN ONO Abstract. This short course is an introduction to the theory of harmonic Maass forms, mock modular forms, and quantum modular forms. These objects have many applications: black holes, Donaldson invariants, partitions and q-series, modular forms, probability theory, singular moduli, Borcherds products, central values and derivatives of modular L-functions, generalized Gross-Zagier formulae, to name a few. Here we discuss the essential facts in the theory, and consider some applications in number theory. This mathematics has an unlikely beginning: the mystery of Ramanujan’s enigmatic “last letter” to Hardy written three months before his untimely death. Section 15 gives examples of projects which arise naturally from the mathematics described here. Modular forms are key objects in modern mathematics. Indeed, modular forms play cru- cial roles in algebraic number theory, algebraic topology, arithmetic geometry, combinatorics, number theory, representation theory, and mathematical physics. The recent history of the subject includes (to name a few) great successes on the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer Con- jecture, Mirror Symmetry, Monstrous Moonshine, and the proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem. These celebrated works are dramatic examples of the evolution of mathematics. Here we tell a different story, the mathematics of harmonic Maass forms, mock modular forms, and quantum modular forms. This story has an unlikely beginning, the mysterious last letter of the Ramanujan. 1. Ramanujan The story begins with the legend of Ramanujan, the amateur Indian genius who discovered formulas and identities without any rigorous training1 in mathematics. He recorded his findings in mysterious notebooks without providing any indication of proofs. -

Contemporary Mathematics 291

CONTEMPORARY MATHEMATICS 291 q-Series with Applications to Combinatorics, Number Theory, and Physics A Conference on q-Series with Applications to Combinatorics, Number Theory, and Physics October 26-28, 2000 University of Illinois Bruce C. Berndt Ken Ono Editors http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/conm/291 Selected Titles in This Series 291 Bruce C. Berndt and Ken Ono, Editors, q-Series with applications to combinatorics, number theory, and physics, 2001 290 Michel L. Lapidus and Machiel van Frankenhuysen, Editors, Dynamical, spectral, and arithmetic zeta functions, 2001 289 Salvador Perez-Esteva and Carlos Villegas-Blas, Editors, Second summer school in analysis and mathematical physics: Topics in analysis: Harmonic, complex, nonlinear and quantization, 2001 288 Marisa Fernandez and Joseph A. Wolf, Editors, Global differential geometry: The mathematical legacy of Alfred Gray, 2001 287 Marlos A. G. Viana and Donald St. P. Richards, Editors, Algebraic methods in statistics and probability, 2001 286 Edward L. Green, Serkan Ho§ten, Reinhard C. Laubenbacher, and Victoria Ann Powers, Editors, Symbolic computation: Solving equations in algebra, geometry, and engineering, 2001 285 Joshua A. Leslie and Thierry P. Robart, Editors, The geometrical study of differential equations, 2001 284 Gaston M. N'Guerekata and Asamoah Nkwanta, Editors, Council for African American researchers in the mathematical sciences: Volume IV, 2001 283 Paul A. Milewski, Leslie M. Smith, Fabian Waleffe, and Esteban G. Tabak, Editors, Advances in wave interaction and turbulence, -

Vitae Ken Ono Citizenship

Vitae Ken Ono Citizenship: USA Date of Birth: March 20,1968 Place of Birth: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Education: • Ph.D., Pure Mathematics, University of California at Los Angeles, March 1993 Thesis Title: Congruences on the Fourier coefficients of modular forms on Γ0(N) with number theoretic applications • M.A., Pure Mathematics, University of California at Los Angeles, March 1990 • B.A., Pure Mathematics, University of Chicago, June 1989 Research Interests: • Automorphic and Modular Forms • Algebraic Number Theory • Theory of Partitions with applications to Representation Theory • Elliptic curves • Combinatorics Publications: 1. Shimura sums related to quadratic imaginary fields Proceedings of the Japan Academy of Sciences, 70 (A), No. 5, 1994, pages 146-151. 2. Congruences on the Fourier coefficeints of modular forms on Γ0(N), Contemporary Mathematics 166, 1994, pages 93-105., The Rademacher Legacy to Mathe- matics. 3. On the positivity of the number of partitions that are t-cores, Acta Arithmetica 66, No. 3, 1994, pages 221-228. 4. Superlacunary cusp forms, (Co-author: Sinai Robins), Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 123, No. 4, 1995, pages 1021-1029. 5. Parity of the partition function, 1 2 Electronic Research Annoucements of the American Mathematical Society, 1, No. 1, 1995, pages 35-42 6. On the representation of integers as sums of triangular numbers Aequationes Mathematica (Co-authors: Sinai Robins and Patrick Wahl) 50, 1995, pages 73-94. 7. A note on the number of t-core partitions The Rocky Mountain Journal of Mathematics 25, 3, 1995, pages 1165-1169. 8. A note on the Shimura correspondence and the Ramanujan τ(n)-function, Utilitas Mathematica 47, 1995, pages 153-160. -

![Arxiv:1911.05264V3 [Math.NT]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9272/arxiv-1911-05264v3-math-nt-3459272.webp)

Arxiv:1911.05264V3 [Math.NT]

A NOTE ON THE HIGHER ORDER TURAN´ INEQUALITIES FOR k-REGULAR PARTITIONS WILLIAM CRIAG AND ANNA PUN Abstract. Nicolas [8] and DeSalvo and Pak [3] proved that the partition function p(n) is log concave for n 25. Chen, Jia and Wang [2] proved that p(n) satisfies the third order ≥ Tur´an inequality, and that the associated degree 3 Jensen polynomials are hyperbolic for n 94. Recently, Griffin, Ono, Rolen and Zagier [5] proved more generally that for all d, ≥ the degree d Jensen polynomials associated to p(n) are hyperbolic for sufficiently large n. In this paper, we prove that the same result holds for the k-regular partition function pk(n) for k 2. In particular, for any positive integers d and k, the order d Tur´an ≥ inequalities hold for pk(n) for sufficiently large n. The case when d = k = 2 proves a conjecture by Neil Sloane that p2(n) is log concave. 1. Introduction and Statement of results The Tur´an inequality (or sometimes called Newton inequality) arises in the study of real entire functions in Laguerre-P´olya class, which is closely related to the study of the Riemann hypothesis [4, 12]. It is well known that the Riemann hypothesis is true if and only if the Riemann Xi function is in the Laguerre-P´olya class, where the Riemann Xi function is the entire order 1 function defined by 1 2 1 iz 1 iz 1 1 Ξ(z) := z π 2 − 4 Γ + ζ iz + . 2 − − 4 − 2 4 − 2 A necessary condition for the Riemann Xi function to be in the Laguerre-P´olya class is that the Maclaurin coefficients of the Xi function satisfy both the Tur´an and higher order Tur´an inequalities [4, 11]. -

![Arxiv:2007.09803V2 [Math.NT] 21 Dec 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7387/arxiv-2007-09803v2-math-nt-21-dec-2020-3737387.webp)

Arxiv:2007.09803V2 [Math.NT] 21 Dec 2020

ON L-FUNCTIONS OF MODULAR ELLIPTIC CURVES AND CERTAIN K3 SURFACES MALIK AMIR, LETONG HONG Abstract. Inspired by Lehmer’s conjecture on the nonvanishing of the Ramanujan τ-function, one may ask whether an odd integer α can be equal to τ(n) or any coefficient of a newform f(z). Balakrishnan, Craig, Ono, and Tsai used the theory of Lucas sequences and Diophantine analysis to characterize non-admissible values of newforms of even weight k 4. We use these methods for weight 2 and 3 newforms and apply our results to L-functions of≥ modular elliptic curves and certain K3 surfaces with Picard number 19. In particular, for the complete list of n ≥ weight 3 newforms fλ(z)= aλ(n)q that are η-products, and for Nλ the conductor of some elliptic curve Eλ, we show thatP if aλ(n) < 100 is odd with n> 1 and (n, 2Nλ) = 1, then | | aλ(n) 5, 9, 11, 25, 41, 43, 45, 47, 49, 53, 55, 59, 61, ∈ {−67, ±69, 71, ±73, 75± , 79− , 81± , 83, ±89, 93± 97,±99 . ± − ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± } Assuming the Generalized Riemann Hypothesis, we can rule out a few more possibilities leaving aλ(n) 5, 9, 11, 25, 45, 49, 55, 69, 75, 81, 93, 99 . ∈ {− ± − − ± ± } 1. Introduction and Statement of the Results In an article entitled “On certain arithmetical functions”, Ramanujan introduced the τ- function in 1916, known as the Fourier coefficients of the weight 12 modular form ∞ ∞ ∆(z)= q (1 qn)24 := τ(n)qn = q 24q2 + 252q3 1472q4 + 4830q5 ... − − − − nY=1 Xn=1 where throughout q := e2πiz. -

2021 Mary P. Dolciani Prize

FROM THE AMS SECRETARY 2021 Mary P. Dolciani Prize Amanda L. Folsom was awarded the 2021 Mary P. Dolciani Prize at the Annual Meeting of the AMS, held virtually January 6–9, 2021. Citation Folsom is an active collaborator with undergraduates, The Mary P. Dolciani Prize successfully bringing students into her research field, and for Excellence in Research is has coauthored five papers with thirteen undergraduate awarded to Amanda L. Folsom, coauthors. Folsom is also a dedicated expositor, working professor of mathematics at to explain her research field as well as aspects of the math- Amherst College, for her out- ematical profession to a more general audience through standing record of research in articles in journals such as the Notices of the American Math- analytic and algebraic number ematical Society and Philosophical Transactions of the Royal theory, with applications to Society A. She has twice been a research advisor and coedited combinatorics and Lie theory, a volume for the Women in Numbers workshops at Banff. She currently serves as Department Chair of Mathematics for her work with undergradu- and Statistics at Amherst. ate students, and for her service Amanda L. Folsom to the profession, including her Biographical Sketch work to promote the success of Amanda L. Folsom received her PhD in mathematics in women in mathematics. 2006 from the University of California at Los Angeles under Folsom’s research centers around the theory of mock the supervision of William Duke. She held postdoctoral modular forms and their relatives. Classical modular forms positions at the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics and are complex functions on the upper half plane that have an the University of Wisconsin-Madison between 2007 and invariance property under the action of the modular group; 2010 and joined the mathematics faculty at Yale University it was a profound study of their relationship to number in 2010. -

Lecture Topics

Ken Ono, Ph.D. Thomas Jefferson Professor of Mathematics, University of Virginia Vice President, American Mathematical Society Chair of Mathematics, American Association for the Advancement of Science Ken Ono is a research mathematician who has a strong interest in issues related to the college experience. He is known for his research in mathematics, and his work in television and film. He was the Associate Producer of the Hollywood film “The Man Who Knew Infinity” about the self-trained Indian mathematical genius Srinivasa Ramanujan, and he starred in an episode of Star Talk hosted by Neil deGrasse Tyson. Public Lecture Option 1: Title: Why does Ramanujan, “The Man Who Knew Infinity,” matter? “Dear Sir…I beg to introduce myself to you as a clerk… of the Port Trust Office at Madras… I have been employing the spare time at my disposal to work at Mathematics…I have not trodden through the conventional regular course…but I am striking out a new path...” What followed in the letter were astonishing mathematical formulas, so otherworldly the letter's recipient could not help but believe they were true. Written in 1913, it has taken mankind one century to understand their meaning; along the way, the pursuit has led to solutions of ancient mathematical mysteries, breakthroughs in modern physics, and ideas which help power the internet. A major motion picture based on the life of the letter’s author, THE MAN WHO KNEW INFINITY, starring Dev Patel and Jeremy Irons, was released in 2016 (Ken Ono is an Associate Producer of the film). The mysterious “clerk of the Port Trust Office of Madras” has been in the air a lot recently. -

Proof of the Elliptic Expansion Moonshine Conjecture of C\U {A} Ld

PROOF OF THE ELLIPTIC EXPANSION MOONSHINE CONJECTURE OF CALD˘ ARARU,˘ HE, AND HUANG LETONG HONG, MICHAEL H. MERTENS, KEN ONO, AND SHENGTONG ZHANG Abstract. Using predictions in mirror symmetry, C˘ald˘araru, He, and Huang recently for- mulated a “Moonshine Conjecture at Landau-Ginzburg points” [6] for Klein’s modular j- function at j = 0 and j = 1728. The conjecture asserts that the j-function, when specialized at specific flat coordinates on the moduli spaces of versal deformations of the corresponding CM elliptic curves, yields simple rational functions. We prove this conjecture, and show that these rational functions arise from classical 2F1-hypergeometric inversion formulae for the j-function. 1. Introduction and statement of results The Monstrous Moonshine Conjecture [8], famously proved by Borcherds [2], offers a sur- prising relationship between the Monster M, the largest sporadic simple group, and gen- erators for the modular function fields of specific genus 0 modular curves. The conjecture sprouted from the observation that the first few coefficients of Klein’s function 1 2 3 (1.1) j(τ) 744 = q− + 196884q + 21493760q + O q , − 2πiτ the Hauptmodul for SL2(Z) with q := e and τ in the upper-half of the complex plane, are simple sums of the dimensions of irreducible representations of M. Monstrous Moonshine [2, 8, 16, 17] offers a graded, infinite-dimensional M-module V ♮ = V ♮(n) n 1 M≥− whose graded dimensions are the coefficients of j(τ) 744. Moreover, for each g M, it provides a genus zero subgroup Γ SL (R) for which− ∈ g ⊆ 2 ♮ n arXiv:2108.01027v1 [math.NT] 2 Aug 2021 T (τ) := Tr g V (n) q , g | n 1 X≥− is the Hauptmodul for Γg.