"Don't Be Evil": Gmail's Relevant Text Advertisements Violate Google's Own Motto and Your E-Mail Privacy Rights Jason Isaac Miller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Deep Dive Into the Technology of Corporate Surveillance

Behind the One-Way Mirror: A Deep Dive Into the Technology of Corporate Surveillance Author: Bennett Cyphers and Gennie Gebhart A publication of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, 2019. “Behind the One-Way Mirror: A Deep Dive Into the Technology of Corporate Surveillance” is released under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). View this report online: https://www.eff.org/wp/behind-the-one-way-mirror ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUNDATION 1 Behind the One-Way Mirror: A Deep Dive Into the Technology of Corporate Surveillance Behind the One-Way Mirror A Deep Dive Into the Technology of Corporate Surveillance BENNETT CYPHERS AND GENNIE GEBHART December 2, 2019 ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUNDATION 2 Behind the One-Way Mirror: A Deep Dive Into the Technology of Corporate Surveillance Introduction 4 First-party vs. third-party tracking 4 What do they know? 5 Part 1: Whose Data is it Anyway: How Do Trackers Tie Data to People? 6 Identifiers on the Web 8 Identifiers on mobile devices 17 Real-world identifiers 20 Linking identifiers over time 22 Part 2: From bits to Big Data: What do tracking networks look like? 22 Tracking in software: Websites and Apps 23 Passive, real-world tracking 27 Tracking and corporate power 31 Part 3: Data sharing: Targeting, brokers, and real-time bidding 33 Real-time bidding 34 Group targeting and look-alike audiences 39 Data brokers 39 Data consumers 41 Part 4: Fighting back 43 On the web 43 On mobile phones 45 IRL 46 In the legislature 46 ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUNDATION 3 Behind the One-Way Mirror: A Deep Dive Into the Technology of Corporate Surveillance Introduction Trackers are hiding in nearly every corner of today’s Internet, which is to say nearly every corner of modern life. -

The Androidaps Alt-Guide Documentation Release Latest

The AndroidAPS alt-Guide Documentation Release latest Sep 18, 2018 Contents 1 Before you Start 3 1.1 Safety first................................................3 1.1.1 General.............................................3 1.1.2 SMS Communicator......................................3 1.2 Useful resources to read before you start................................3 1.2.1 DIY Artificial Pancreas articles.................................4 1.2.2 Blogs..............................................4 1.2.3 Stuff on YouTube........................................4 1.2.4 Press Articles..........................................4 1.2.5 Position Statements on DIY Artificial Panchreas systems...................4 1.3 Press releases and other articles about DIY closed looping.......................4 1.4 Glossary.................................................5 2 Understanding AndroidAPS 7 2.1 Understanding the AndroidAPS screens.................................7 2.1.1 The Overview screen......................................8 2.1.2 The Calculator......................................... 10 2.1.3 Carbs.............................................. 12 2.1.4 Actions............................................. 14 2.1.5 Insulin Profile.......................................... 15 2.1.6 Pump Status........................................... 17 2.1.7 Care Portal........................................... 19 2.1.8 Loop, OpenAPS AMA..................................... 20 2.1.9 Profile.............................................. 22 2.1.10 Treatment, xDrip, NSClient.................................. -

Insight MFR By

Manufacturers, Publishers and Suppliers by Product Category 11/6/2017 10/100 Hubs & Switches ASCEND COMMUNICATIONS CIS SECURE COMPUTING INC DIGIUM GEAR HEAD 1 TRIPPLITE ASUS Cisco Press D‐LINK SYSTEMS GEFEN 1VISION SOFTWARE ATEN TECHNOLOGY CISCO SYSTEMS DUALCOMM TECHNOLOGY, INC. GEIST 3COM ATLAS SOUND CLEAR CUBE DYCONN GEOVISION INC. 4XEM CORP. ATLONA CLEARSOUNDS DYNEX PRODUCTS GIGAFAST 8E6 TECHNOLOGIES ATTO TECHNOLOGY CNET TECHNOLOGY EATON GIGAMON SYSTEMS LLC AAXEON TECHNOLOGIES LLC. AUDIOCODES, INC. CODE GREEN NETWORKS E‐CORPORATEGIFTS.COM, INC. GLOBAL MARKETING ACCELL AUDIOVOX CODI INC EDGECORE GOLDENRAM ACCELLION AVAYA COMMAND COMMUNICATIONS EDITSHARE LLC GREAT BAY SOFTWARE INC. ACER AMERICA AVENVIEW CORP COMMUNICATION DEVICES INC. EMC GRIFFIN TECHNOLOGY ACTI CORPORATION AVOCENT COMNET ENDACE USA H3C Technology ADAPTEC AVOCENT‐EMERSON COMPELLENT ENGENIUS HALL RESEARCH ADC KENTROX AVTECH CORPORATION COMPREHENSIVE CABLE ENTERASYS NETWORKS HAVIS SHIELD ADC TELECOMMUNICATIONS AXIOM MEMORY COMPU‐CALL, INC EPIPHAN SYSTEMS HAWKING TECHNOLOGY ADDERTECHNOLOGY AXIS COMMUNICATIONS COMPUTER LAB EQUINOX SYSTEMS HERITAGE TRAVELWARE ADD‐ON COMPUTER PERIPHERALS AZIO CORPORATION COMPUTERLINKS ETHERNET DIRECT HEWLETT PACKARD ENTERPRISE ADDON STORE B & B ELECTRONICS COMTROL ETHERWAN HIKVISION DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY CO. LT ADESSO BELDEN CONNECTGEAR EVANS CONSOLES HITACHI ADTRAN BELKIN COMPONENTS CONNECTPRO EVGA.COM HITACHI DATA SYSTEMS ADVANTECH AUTOMATION CORP. BIDUL & CO CONSTANT TECHNOLOGIES INC Exablaze HOO TOO INC AEROHIVE NETWORKS BLACK BOX COOL GEAR EXACQ TECHNOLOGIES INC HP AJA VIDEO SYSTEMS BLACKMAGIC DESIGN USA CP TECHNOLOGIES EXFO INC HP INC ALCATEL BLADE NETWORK TECHNOLOGIES CPS EXTREME NETWORKS HUAWEI ALCATEL LUCENT BLONDER TONGUE LABORATORIES CREATIVE LABS EXTRON HUAWEI SYMANTEC TECHNOLOGIES ALLIED TELESIS BLUE COAT SYSTEMS CRESTRON ELECTRONICS F5 NETWORKS IBM ALLOY COMPUTER PRODUCTS LLC BOSCH SECURITY CTC UNION TECHNOLOGIES CO FELLOWES ICOMTECH INC ALTINEX, INC. -

Maximizing Google Analytics with Miva Merchant

Maximizing Google Analytics With Miva Merchant Morgan Jones eCommerce Intelligence February 29, 2008 1 Agenda • What is Google Analytics? • Cool features • New cool features recently released •Q&A 2 eCommerce Intelligence • Internet Marketing Consulting • Search Engine Marketing – SEO (Natural/Organic Search) – SEM (Pay-Per-Click) • Miva and Google Partner – Google products – Analytics, Website Optimizer, AdWords • Analytics consulting company—GAAC – Focus is Google Analytics and Urchin • Strategic marketing/business consulting • Metrics-based marketing – data-driven 3 eComIQ Background Morgan Jones (President) – GreekInternetMarket.com founder – Using GA since it was called “Urchin” Steve Gott (CTO) – Former Urchin employee – Urchin/GA consultant prior to eComIQ 4 What is Google Analytics? Tons of website data! – Visits – Where visitors from – What search engines sent traffic – Referring sites – New vs. returning visitors – Where visitors exited site – % of visitors who reached a goal – % of visitors who made a purchase – Much, much more! 5 Key GA Features 6 Key GA Features 7 Custom Dashboard • Customize to your key metrics and business needs • Easy to modify • View daily and spend 1 minute getting a snapshot of your business for the previous day. • Dive in to take action. 8 Traffic Sources 9 AdWords Integration And “Finding Your Niche” Case Study Muttmart.com • Big market (pet supplies) • Very competitive market – Petco, Petsmart, local competition. • Needed a niche 10 AdWords Integration And “Finding Your Niche” Case Study • Installed Google Analytics Dec 2006 and began consulting on monthly basis • MuttMart added focus to one particular product line and was able to drive down cost • AdWords keywords initially contained all breeds and sizes when advertising this particular product line 11 AdWords Integration And “Finding Your Niche” Case Study Found “niche” in GA reports when looking AdWords ROI per keyword. -

Google: the World's First Information Utility?

BISE – STATE OF THE ART Google: The World’s First Information Utility? The idea of information utilities came to naught in the 70s and 80s, but the world wide web, the Internet, mobile access, and a plethora of access devices have now made information utilities within reach. Google’s business model, IT infrastructure, and innovation strategies have created the capabilities needed for Google to become the world’s first global information utility. But, the difficulty of monetizing utility services and concerns about privacy, which could bring government regulation, might stymie Google’s growth plans. DOI 10.1007/s12599-008-0011-6 a national scale (Sackmann and Nie 1970; the number of users to the point where it The Authors Sackman and Boehm 1972). Not to be left is the dominant search player in both the out, the idea was also promoted by the U.S. and the world. This IT-based strategy Rex Chen Computer Usage Development Institute has allowed Google to reach more than Prof. Kenneth L. Kraemer, PhD in Japan, the British Post Office in the UK, $16 billion in annual revenue, a stock price Prakul Sharma and Bell Canada and the Telecommunica- over $600 per share and a market capital- University of California, Irvine tions Board in Canada (Press 1974). ization of nearly $200 billion. Center for Research on Information The idea was so revolutionary at the Over the next decade, Google plans to Technology and Organization (CRITO) time that at least one critic called for a extend its existing services to the wire- 5251 California Ave., Ste. -

2015 Tbilisi

NATIONAL INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY CENTER OF GEORGIA SAKPATENTI 11(423) 2015 TBILISI INID CODES FOR IDENTIFICATION OF BIBLIOGRAPHIC DATA LIST OF CODES, IN ALPHABETIC SEQUENCE, AND THE CORRESPONDING (SHORT) NAMES OF STATES, OTHER ENTITIES AND INTERGOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS (WIPO STANDARD ST.3) INVENTIONS, UTILITY MODELS (10) Number of publication for application, which has been examined (54) Title of the invention AD Andorra for the Arab States of the Gulf (GCC) NE Niger (11) Number of patent and kind of document (57) Abstract AE United Arab Emirates GD Grenada NG Nigeria (21) Serial number of application (60) Number of examined patent document granted by foreign patent office, date from which patent AF Afghanistan GG Guernsey NI Nicaragua (22) Date of filing of the application has effect and country code (62) Number of the earlier application and in case of divided application, date of filing an AG Antigua and Barbuda GH Ghana NL Netherlands (23) Date of exhibition or the date of the earlier filing and the number of application, if any application AI Anguilla GI Gibraltar NO Norway (24) Date from which patent may have effect (71) Name, surname and address of applicant (country code) AL Albania GT Guatemala NP Nepal (31) Number of priority application (72) Name, surname of inventor (country code) AM Armenia GW Guinea- Bissau NR Nauru (32) Date of filing of priority application (73) Name, surname and address of patent owner (country code) AN Netherlands Antilles GY Guyana NZ New Zealand (33) Code of the country or regional organization allotting -

Cookies Policy

Cookies policy At SUNBORN (GIBRALTAR) RESORT LTD.we comply with the provisions of the Law on Information Society Services, a regulation gathered in the transposition of Directive 2009/136/CE. What is a cookie? A cookie is a small text file which is stored on a computer, tablet, mobile telephone or, ultimately, on the device used to browse the Internet. This file can store information related to the frequency with which you visit websites, your browsing preferences, the information you are most interested in, usernames, product registration, etc. Depending on the information they contain and the way in which the device is used, they may be used to recognise the user. Cookie types Depending on their nature, cookies can be classified into: ‘Session cookies’ or ‘Persistent cookies’: The former are deleted when the browser is closed, whilst the latter remain on the computer device. ‘First-party cookies’ or ‘Third-party cookies’: depending on whether they belong to the website’s owner or to a third party. Depending on their purpose, they can be: ‘Technical cookies’: Those which allow the user to browse on a website, platform or application and the use of the different options and services which exist within, such as, for example, controlling web traffic and data communication, identifying the session, accessing restricted areas, registering the elements which make up an order, carrying out the purchasing process of an order, carrying out a registration or event-participation request, using security elements during browsing, storing contents to disseminate videos or sound files or sharing contents through social networks. ‘Personalisation cookies’: Those which allow the user to access the service with some predefined general characteristics according to a series of criteria from the user’s terminal equipment, such as language, browser type through which the service is accessed, regional settings from where the service is accessed, etc. -

Introducing Google Analytics for Libraries

Chapter 1 Introducing Google Analytics for Libraries Abstract Google Analytics www.google.com/analytics Google Analytics continues to evolve into a more robust web analytics tool, and libraries must stay informed on these developments to get the most out of the tool. Chap- In fact, many libraries are already using it. A brief ter 1 of Library Technology Reports (vol. 49, no. 4) review of library literature shows that libraries are “Maximizing Google Analytics: Six High-Impact Prac- actively using web analytics and are using Google tices” introduces the high impact practices essential to Analytics as their primary web analytics tool.1 So why Google Analytics and provides a brief history of the tool to is this issue of Library Technology Reports dedicated show how it has developed since first launched in 2005. to Google Analytics if libraries are already using it? The authors share the benefits and limitations of Google Because Google Analytics is as wonderfully complex Analytics and conclude with additional resources to help as it is useful. You can easily implement it, but with libraries maximize usage. further customizations you and your library can use Google Analytics to its full capacity. This report covers oogle Analytics is a widely used, free web ana- common customizations and concepts libraries should lytics tool that collects, analyzes, and reports implement to have a fully functional web analytics ReportsLibrary Technology Gwebsite traffic data. Its price tag alone makes tool. We have distilled this information into six high- it a very desirable option for libraries to adopt, but impact practices that are worth investing in: Google Analytics is also a powerful tool that offers a wide range of reports and features not found in other • implementation of Google Analytics on various web analytics tools on the market. -

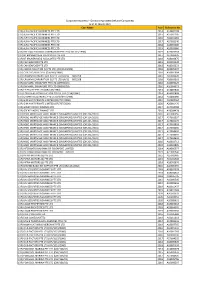

Defunct Companies) As at 31 March 2021 Case Name Yearreference No

Corporate Insolvency - Outstanding Assets (Defunct Companies) as at 31 March 2021 Case Name YearReference No. (DF) ALFA-PACIFIC NOMINEES PTE LTD 2014 A14002198 (DF) ALFA-PACIFIC NOMINEES PTE LTD 2015 A15001105 (DF) ALFA-PACIFIC NOMINEES PTE LTD 2016 A16002481 (DF) ALFA-PACIFIC NOMINEES PTE LTD 2017 A17002340 (DF) ALFA-PACIFIC NOMINEES PTE LTD 2018 A18002680 (DF) ALFA-PACIFIC NOMINEES PTE LTD 2019 A19009686 (DF) BEE LIAN BUILDING CONTRACTOR PTE LTD ( OR 373/1998 ) 2019 A19007268 (DF) BT BROKERAGE & ASSOCIATES PTE LTD 2017 A17003225 (DF) BT BROKERAGE & ASSOCIATES PTE LTD 2018 A18003875 (DF) CAK SEAFOOD PTE LTD 2018 A18002228 (DF) CAK SEAFOOD PTE LTD 2018 A18002253 (DF) CANON SOLUTION (S) PTE LTD; (OR/652/2004) 2018 A18005037 (DF) CITY SECURITIES PTE (CW/450/1986) 2016 A16001604 (DF) CROWM CORPORATION (S) PTE LTD OR/11 88/1998 2015 A15002420 (DF) CROWM CORPORATION (S) PTE LTD OR/11 88/1998 2016 A16003502 (DF) DAIMARU SINGAPORE PTE LTD (OR993/03) 2016 A16003125 (DF) DAIMARU SINGAPORE PTE LTD (OR993/03) 2016 A16004673 (DF) EE REALTY PTE LTD (OR/537/1993) 2014 A14002840 (DF) FOUR SEAS CONSTRUCTION CO PTE LTD ( 314/1998 ) 2014 A14002808 (DF) GAMMA ELECTRONIC PTE LTD (CW/397/1986) 2014 A14000086 (DF) GIM HUAT PRIVATE LIMITED (OR/797/2000) 2019 A19007464 (DF) GIM HUAT PRIVATE LIMITED (OR/797/2000) 2020 A20001470 (DF) GREAT PACIFIC FINANCE LTD 2017 A17004788 (DF) GREAT PACIFIC FINANCE LTD 2018 A18004478 (DF) HSBC MORTGAGE AND FINANCE (SINGAPORE) LIMITED (OR 204/2001) 2016 A16000955 (DF) HSBC MORTGAGE AND FINANCE (SINGAPORE) LIMITED (OR 204/2001) -

Cookie Policy

DIA GROUP BV COOKIE POLICY INFORMATION ABOUT COOKIES This cookie policy explains how cookies and similar technologies (together, cookies) are used on the websites (including main website www.digitalinsuranceagenda.com) of DIA GROUP BV and its subsidiaries. The first time you visit our website, we inform you about the use of cookies through a pop up banner. You can choose which cookies you accept and which not. You can change your settings at any time on the Privacy Settings page on our website. We use Google Tag Manager to manage the cookies on our websites. You find a list of the cookies we use below. Cookies may also be placed or managed by third parties on behalf of us, such as Bizzabo and Google Tag Manager. Technical cookies and cookies that are necessary for the operation of the website or the provision of services specifically requested by you are not subject to your consent. When we use tracking cookies, personal data may be stored, such as your IP address. Please refer to our Privacy Policy for information about how we treat your personal data. WHAT ARE COOKIES? Cookies and other similar technologies, such as local shared objects, flash cookies and pixels (jointly referred to as “cookies” in this policy), are used to store and retrieve information about visitors of our website as well as to ensure that the website operates correctly. These tools store and in some cases track certain information about users, such as their browsing preferences on the site, their name and password, the products they are most interested in, etc. -

Five Panelists Take on Your Hottest GA4 Questions

LIVE Q&A Five Panelists Take On Your Hottest GA4 Questions . © 2020 Seer Interactive • All Rights Reserved • Page 1 Who you’ll be hearing from … Our panelists leading discussion Our panelists available for Live Chat + Q&A © 2020 Seer Interactive • All Rights Reserved • Page 2 Poll #1 © 2020 Seer Interactive • All Rights Reserved • Page 3 Poll #1 - Live Responses © 2020 Seer Interactive • All Rights Reserved • Page 4 GA4 Introduction: What is it? Why now? What are the main benefits? © 2020 Seer Interactive • All Rights Reserved • Page 5 Simply put, Google Analytics 4 (GA4) represents a paradigm shift. © 2020 Seer Interactive • All Rights Reserved • Page 6 What led to Google’s decision to replatform the product now? 2005 2015 2019 2020 2021 ….. Google Analytics Universal GA App + Web GA4 BETA GA4 Launch to is Born (Urchin) Analytics Launch BETA Launch Launch All Users Google acquired After being Google unifies app App + Web moves GA4 becomes Urchin Software launched in BETA and web analytics by out of BETA and is available to all users, Corporation, in 2014, Google launching a new relaunched as GA4 defaulting in new eventually rolling out launched UA to property type for BETA with a property creation Google Analytics in better collect and App + Web. machine learning being G4 or November 2005. organize GA data. model. upgrading an existing property to GA4. © 2020 Seer Interactive • All Rights Reserved • Page 7 What are the main benefits of GA4? Leverage a user-centric data model. Understand user journey across devices and platforms with unified, deduplicated data using your 1st party data and Google’s. -

Google Analytics & Google Tag Manager Workshop Welcome About Lunametrics

Google Analytics & Google Tag Manager Workshop Welcome About LunaMetrics LunaMetrics is a Digital Marketing & Google Analytics consultancy helping businesses use data to illuminate the bridge between marketing, user behavior and ROI. Our core consulting competencies are in Google Analytics and Digital Marketing Strategy. 2 Welcome Ok, So Who Is This? Jon Meck Senior Director, Marketing [email protected] 3 Welcome Who are you? Techie Marketer Super Human 4 Welcome Fun Facts: Me I write puzzle books for fun! I have two kids, Lucca (4) and Rosie (1). (Forgive me for my dad jokes.) I try to attend concerts in every city I visit for work! 5 Welcome Fun Facts: We Do Trainings! 6 Welcome Fun Facts: Training Options We hold a few different trainings across the country! In Chicago 3x a year, and actually here next week! Subject Classes Google Analytics 101 201 301 Google Ads 101 201 Google Tag Manager 101 Google Data Studio 101 Google Optimize 101 Learn more about our trainings Google Analytics 101 7 Welcome Fun Facts: Share & Raise Money /LunaMetrics @lunametrics /LunaMetrics #LunaTraining #ContentJam Google Analytics 101 8 Welcome Three Main Goals 1. Understand how Google Analytics and Google Tag Manager work together. Understand how to implement. 2. Learn about Google Analytics events; how we can use GTM to add event tracking to our site, and event reports to better understand users’ actions. 3. Learn about Google Analytics custom dimensions; how we can use GTM to pass extra info to GA, and how this helps our reporting. 9 How Does It All Fit Together? 10 Suite Recent Google Changes 11 Suite Google Marketing Platform 12 Suite Google Marketing Platform Off Your Site On Your Site Reporting In GA Sending Recording Traffic Activity 13 Suite Google Analytics Google Analytics is a tool that we use to capture, sort, classify, and report on users’ actions on and off our site.