An Analysis of Milb Salaries and Cost of Living: How Does the Ability to Live on Milb Salaries Differ Based on Player Contract and City?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BEN MCDONALD'sauthenticity

bring your kids ages 9 and under for free PA GE major sporting events that should happen in baltimore 244 05.18 BEN MCDONALD’S authenticity has made him a fan-favorite for years, however, his transition from player to commentator was anything but seamless BY KEVIN ECK > Page 16 photography > courtesy of the baltimore orioles of the baltimore photography > courtesy VISIT BUYATOYOTA.COM FOR GREAT DEALS! buyatoyota.com UPCOMING PROMOTIONS AT ORIOLE PARK may 31- vs. May vs. 15-16 June 3 MAY 16 JUNE 1 FRIDAY FIREWORKS & MUSIC FIELD TRIP DAY POSTGAME, ALL FANS PRESENTED BY WJZ-TV PRE-REGISTERED STUDENTS STUDENT NIGHT ALL STUDENTS, SUBJECT TO AVAILABILITY JUNE 2 THE SANDLOT MOVIE NIGHT May POSTGAME, ALL FANS SPECIAL TICKET PACKAGES AVAILABLE vs. 28-30 JUNE 3 MAY 28 KIDS RUN THE BASES PRESENTED BY WEIS MARKETS ORIOLES MEMORIAL DAY T-SHIRT POSTGAME, ALL KIDS AGES 4-14 ALL FANS MAY 30 ORIOLES COOLER BACKPACK June vs. PRESENTED BY VISIT SARASOTA FIRST 20,000 FANS 15 & OVER 11-13 JUNE 12 DYLAN BUNDY BOBBLEHEAD FIRST 25,000 FANS 15 & OVER bring your kids ages 9 and under for free Issue 244 • 5.15.18 - table of contents - COVER STORY Ben’s Second Act......................................................16 Ben McDonald’s authenticity has made him a fan-favorite for years, however, his transition from player to commentator was anything but seamless By Kevin Eck play, FEATURE STORIES meet stay Sports Business w/ Baltimore Business Journal...... 08 Maryland Gaming w/ Bill Ordine ............................12 Ravens Report w/ Bo Smolka.................................... 13 Orioles Report w/ Rich Dubroff............................. -

Game Information

GAME INFORMATION Atlanta Braves Baseball Communications Department • Truist Park • Atlanta, GA 30339 404.522.7630 braves.com bravesmediacenter.com /braves @braves @braves ATLANTA BRAVES (68-58, 1st NL East, +5.5 GA) Braves vs. Giants 2018 2019 All-Time vs. Overall (since 1900) 3-3 5-2 952-1135-18 SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (83-44, 1st NL West, +2.5 GB) Atlanta Era (since 1966) --- --- 338-344-1 at Atlanta 0-3 2-1 185-156-1 LH Max Fried (11-7, 3.49) vs. RH Kevin Gausman (12-5, 2.47) at Truist Park --- --- 5-5 Game No. 127 • Home Game No. 63 at Turner Field (‘97-’16) -- --- 45-29-1 at SF (since 1966) 3-0 3-1 153-188 August 27, 2021 • 7:20 p.m. • Truist Park • Atlanta, GA • BSSO at Oracle Park (‘00) --- --- 30-36 Dansby Swanson TONIGHT'S GAME: The Braves and Giants open FRIED LAST START: LHP Max Fried last started SS Dansby Swanson gave Atlanta a 2-0 lead up a three-game set tonight with the first of six games on August 20 at Baltimore and pitched the first shutout in the first inning Tuesday night, lining his between the clubs this season...Atlanta will travel to San of his career, holding the Orioles to just four hits on the 30th double into left-center field. Francisco for three games, September 17-19, to kick off night while striking out four...He completed the game He is the only primary shortstop in baseball the Braves' final road trip of the season. -

Liberty Media Corporation Owns Interests in a Broad Range of Media, Communications and Entertainment Businesses

2021 PROXY STATEMENT 2020 ANNUAL REPORT YEARS OF LIBERTY 2021 PROXY STATEMENT 2020 ANNUAL REPORT LETTER TO SHAREHOLDERS STOCK PERFORMANCE INVESTMENT SUMMARY PROXY STATEMENT FINANCIAL INFORMATION CORPORATE DATA ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS Certain statements in this Annual Report constitute forward-looking statements within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, including statements regarding business, product and marketing plans, strategies and initiatives; future financial performance; demand for live events; new service offerings; renewal of licenses and authorizations; revenue growth and subscriber trends at Sirius XM Holdings Inc. (Sirius XM Holdings); our ownership interest in Sirius XM Holdings; the recoverability of goodwill and other long- lived assets; the performance of our equity affiliates; projected sources and uses of cash; the payment of dividends by Sirius XM Holdings; the impacts of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19); the anticipated non-material impact of certain contingent liabilities related to legal and tax proceedings; and other matters arising in the ordinary course of business. In particular, statements in our “Letter to Shareholders” and under “Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations” and “Quantitative and Qualitative Disclosures About Market Risk” contain forward looking statements. Where, in any forward-looking statement, we express an expectation or belief as to future results or events, such expectation or belief -

Language Arts

2013 EDUCATION DAYS At Wednesday, April 10th @ 10:05 am Monday, April 29th @ 10:05 am Wednesday, May 15th @ 10:05 am Curriculum Guide Including Kentucky’s Learning Goals and Academic Expectations IMPORTANT: PLEASE READ BEFORE CONTINUING This curriculum guide was created to provide you with a learning “compass” to help guide your students through a truly rewarding “out of class” experience. The ideas and lesson plans included within stand to serve as a guide to educators to create educational, appropriate ideas to assist in the “Education Day” at Whitaker Bank Ballpark. The curriculum has been designed by educators for educators. It is intended to help provide activities toward meeting Kentucky’s Learning Goals and Academic Expectations. For your convenience, the Learning Goals and Academic Expectations are listed within the curriculum. Regardless of the activity, the procedures and methods can easily be substituted to fit your appropriate grade level. This curriculum has been organized with the following in mind: . Educators tailor their lesson plans to meet the needs of their students. Educators may use bits and pieces of a lesson plan to create their own lesson plans. Educators have the flexibility to use this curriculum to integrate ideas into current studies. This curriculum guide has been divided into four basic areas of study: MATHEMATICS, SCIENCE, SOCIAL STUDIES, and LANGUAGE ARTS. Within each of these four areas of study, we have further divided them into two distinct sub-headings: FOCUSED LESSON PLANS and EXTENDED IDEAS. Focused Lesson Plans: With at least three samples per section, these lesson plans have been designed as a complete, top-to-bottom lesson plan. -

Liberty Media Corporation Owns Interests in a Broad Range of Media, Communications and Entertainment Businesses

Annual REPORT Proxy STATEMENT 2019 2018 Annual REPORT Proxy STATEMENT LETTER TO SHAREHOLDERS STOCK PERFORMANCE INVESTMENT SUMMARY PROXY STATEMENT FINANCIAL INFORMATION CORPORATE DATA ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT Certain statements in this Annual Report constitute forward-looking • changes in the nature of key strategic relationships with partners, statements within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform vendors and joint venturers; Act of 1995, including statements regarding our business, product and • general economic and business conditions and industry trends; marketing strategies and initiatives; new service offerings; revenue and subscriber growth at Sirius XM Holdings Inc. (“SIRIUS XM”); the • consumer spending levels, including the availability and amount of recoverability of our goodwill and other long-lived assets; the performance individual consumer debt; of our equity affiliates; our projected sources and uses of cash; the • rapid technological changes; payment of dividends by SIRIUS XM; the expected benefits of SIRIUS XM’s acquisition of Pandora; the continuation of our stock repurchase program; • impairments of third-party intellectual property rights; monetization of sports media rights; plans for the Battery Atlanta; the • our indebtedness could adversely affect operations and could limit the anticipated non-material impact of certain contingent liabilities related to ability of our subsidiaries to react to changes in the economy or our legal and tax proceedings; and other matters arising in the ordinary course industry; of business. In particular, statements in our “Letter to Shareholders” and under “Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition • failure to protect the security of personal information about our and Results of Operations” and “Quantitative and Qualitative Disclosures businesses’ customers, subjecting our businesses to potentially costly About Market Risk” contain forward looking statements. -

August 2014 Member Newsletter Final Draft for Online

THE PORTS AGE Vol. I, Issue I P Summer 2014 SNews from the Babe Ruth Birthplace and Sports Legends Museum The Babe Ruth Birthplace presents INSIDE THIS ISSUE “BABE RUTH: 100 YEARS” By Patrick Dickerson Home Runs. The highest 714 all-time slugging percentage. It all began on July 11, 1914 when George Herman “Babe” Ruth began his professional career with the Boston Red Sox—the career we celebrate in our newest Celebrate Babe Ruth’s 100 year exhibition, “Babe Ruth: 100 anniversary of joining Major Years.” League Baseball with the Director Mike Gibbons and interesting facts on page 3. Board Chairman John Moag opened the exhibit on June 26 in the Babe Ruth Birthplace’s first floor gallery, featuring both collection favorites and never- before-seen pieces. Babe’s 60 home run season bat returns to public display along with his 1914 Orioles’ rookie card, his catholic rosary that he carried to his death in 1948, and the original marriage certificate from his wedding to Helen Kids, look at the Kids Corner on Woodford in Ellicott City, Maryland. They bring to life both Ruth page 4 for a special the professional and Ruth the person, from his beginnings with Jack Babe Ruth puzzle. Dunn’s Baltimore Orioles to his final days battling cancer. The “Babe” loved to tell a story. Visitors to our new exhibit can hear those stories from Ruth himself through interactive historic audio recordings. Listen up as Babe shares his memories of 1914 spring training in Fayetteville and his larger-than-life slugging records. Another Ruth memory comes to life Just down the hall in our acclaimed film, “The Star-Spangled Banner in Sports,” winner of the 2013 International Sports Heritage Association Communications Award. -

Sod Poodles Announce 2021 Season Schedule Sod Poodles to Host 60 Home Games at HODGETOWN in 2021, Home Opener Set for Tuesday, May 18

For Immediate Release Contact: [email protected] Sod Poodles Announce 2021 Season Schedule Sod Poodles To Host 60 Home Games at HODGETOWN in 2021, Home Opener Set For Tuesday, May 18 AMARILLO, Texas (Feb 18, 2021) — Major League Baseball announced today the complete Sod Poodles schedule for the 2021 Minor League Baseball season. The season comprises 120 regular-season games, 60 at home and 60 on the road, and will begin on Tuesday, May 4 and run through Sunday, September 19. The Sod Poodles 2021 campaign begins on the road with a Championship rematch against the Tulsa Drillers, Double-A affiliate of the Los Angeles Dodgers. The 2021 home opener at HODGETOWN is scheduled for Tuesday, May 18 against the Midland RockHounds, Double-A affiliate of the Oakland Athletics. “We couldn’t be more excited to announce to our community, the best fans in baseball, that the wait is over and Sod Poodles baseball is officially coming back to HODGETOWN this May,” said Sod Poodles President and General Manager Tony Ensor. “The 2019 season was the storybook year we all dreamt about and now it’s time to create new memories and see the future Major League stars of our new MLB affiliate team, the Arizona Diamondbacks. The future of baseball and entertainment in Amarillo is bright with the return of the Sod Poodles this summer and our new 10-year partnership with the D-backs!” In 2021, each team in the Double-A Central will play a total of 20 series, 10 at home and 10 on the road. -

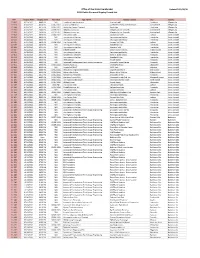

Office of the State Fire Marshal 2021 Public Firework Display Permit List

Office of the State Fire Marshal Updated 2021/09/30 2021 Public Firework Display Permit List 2021 Display Date Display Time Rain Date App. Name Display Location City County 21-004 03/19/2021 0800 PM N/A Frostburg State University Practive Field Frostburg Allegany Co 21-173 07/04/2021 0930 PM 07/05/2021 City of Cumberland Cumberland Parks and Recreation Cumberland Allegany Co 21-190 07/04/2021 0915 PM 07/05/2021 Rocky Gap Casion / Resport Rocky Gap Flintstone Allegany Co 21-143 07/18/2021 1000 PM 07/19/2021 Allegany County Fair Allegany Co Fair Grounds Cumberland Allegany Co 21-144 07/23/2021 1030 PM 07/24/2021 Allegany County Fair Allegany Co Fair Grounds Cumberland Allegany Co 21-003 02/03/2021 0830 PM 02/06/2021 The Cannon Club Cannon Golf Club Lothion Anne Arundel 21-023 04/10/2021 0830 PM N/A Herrington on the Bay Herrington on the Bay Friendship Anne Arundel 21-024 04/28/2021 0830 PM N/A Herrington on the Bay Herrington on the Bay Friendship Anne Arundel 21-035 05/07/2021 0830 PM 05/08/2021 The Cannon Club Cannon Golf Club Lothian Anne Arundel 21-049 05/20/2021 0830 PM N/A Herrington on the Bay Weatherly Farm Friendship Anne Arundel 21-120 06/10/2021 0915 PM N/A Herrington on the Bay Weavers Field Friendship Anne Arundel 21-117 06/12/2021 0915 PM N/A Stephen Bisbee Gibson Island Club Inc. Gibson Island Anne Arundel 21-025 06/18/2021 0930 PM N/A Herrington on the Bay Herrington on the Bay Friendship Anne Arundel 21-102 06/19/2021 0915 PM N/A Pyrotecnico Fireworks Wiley H. -

Oct 0 4 1994

- -- ffgfffi --- - "I -- - -. -, I THE FATE OF THE WHITE ELEPHANT: AN EVALUATION AND ANALYSIS OF THE FACTORS WHICH DETERMINE DEMOLITION OR CONTINUED USE OF MAJOR LEAGUE STADIUMS AND ARENAS IN NORTH AMERICA by Robert J. Hentschel Bachelor of Arts, Geography University of Vermont (1988) Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Real Estate Development at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 1994 @ 1994 Robert J. Hentschel All rights reserved The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author Department of Urban Studies and Planning Aut 5, 1994 Certified by J. Mark Schuster Associate Professor, partment of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by- William C. Wheaton Chairman Interdepartmental Degree Program in Real Estate Development MASSA is r OCT 0 4 1994 Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MIT'Libraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Best copy avaialble. THE FATE OF THE WHITE ELEPHANT: AN EVALUATION AND ANALYSIS OF THE FACTORS WHICH DETERMINE DEMOLITION OR CONTINUED USE OF MAJOR LEAGUE STADIUMS AND ARENAS IN NORTH AMERICA by Robert J. -

Wait Til You See the Deal We Hatched See Back Page

WAIT TIL YOU SEE THE DEAL WE HATCHED SEE BACK PAGE SEPTEMBER 3-9, 2008 ATLANTA’SATLANTA’S WEEKLY SPORTS SPORTS TALK TALK NEWSPAPER NEWSPAPER VOL 4 NO 36 02 I SCORE ATLANTA Get In The Game! WWW.SCOREATL.COM SEPTEMBER 3-9, 2008 SCORE ATLANTA I 03 ™ STARTING LINEUP IN YOUR PUBLISHER/EDITOR I.J. Rosenberg FACE… MANAGING EDITOR Tad Arapoglou DIRECTOR OF SALES/MARKETING John Duke ART/CREATIVE DIRECTOR David Gaudio GRAPHIC DESIGNER D.J. Galbiati WEBMASTER Alex Ewalt VIDEO MANAGER/PREP EDITOR Scott Janovitz WWW.SCOREATL.COM BUSINESS MANAGER Marvin Botnick SALES Zander Lentz, Brian Pruett 14 With the Falcons kicking off the 2008 season on Sunday, beat writer Erik PHOTOGRAPHER Scott Cunningham Horne gives readers the inside scoop on the players, coaches and schedule. OFFICE MANAGER Nakia Washington _______________________________________________________________ BEAT WRITERS Josh Bagriansky (Dream), Stephen Black (Silverbacks), Jason Boral (Thrashers), James Butler 15 Tad Arapoglou breaks down each of the NFL divisions. Braylon (UGA), Dave Cohen (Georgia State), Johnny Crosskey Edwards (pictured) and the Browns could surprise people in (Tech), Alex Ewalt (Preps), Erik Horne (Falcons), Scott the AFC North once again. Janovitz (Hawks/Recruiting), Fletcher Proctor (Braves) ________________________________________________________ STAFF WRITERS Cranston Collier, Joe Deighton, Keilah Johnson, Zander Lentz, Corey Mitchell, Jessica Parker, 23 Kevin Dankosky lists four reasons why the Falcons “won’t be Leighton Savary, Keafer Triplett, Derek Wiley bad” this -

877-446-9361 Tabletable of of Contentscontents

Hill Kelly Ad 6171 Pensacola Blvd Pensacola, FL 32505 877-446-9361 TableTABLE Of OF ContentsCONTENTS 2-4 Blue Wahoos Join Twins Territory 6 Blue Wahoos Stadium 10-11 New Foods, New Views Concessions Storefronts 13 Promotional Calendar 15 Twins Affiliates/Road To The Show 16 Manager Ramon Borrego 17 Coaching Staff 20-24 Player Bios 26 Admiral Fetterman 27 2019 Schedule 28-29 Scorecard 32-35 Pass The Mic: Broadcaster Chris Garagiola 37 Southern League Teams 39-42 Devin Smeltzer: Helping Others Beat Odds 44 How Are We Doing? 48-49 SCI: Is Your Child Ready? 53 Community Initiatives 54 Community Spotlight: Chloe Channell 59 Ballpark Rules 2019 Official Program Double-A Affiliate Minnesota Twins Blue Wahoos Join Twins Territory The Pensacola Blue Wahoos and the Minnesota Twins agreed to a two-year player development agreement for the 2019 and 2020 seasons. The new partnership will bring some of the most exciting prospects in the game to Blue Wahoos Stadium alongside the storied legacy of Twins baseball. Twins history began in 1961 when Washington Senators president Calvin Griffith made the historic decision to move his family’s team to the Midwest, settling on the Minneapolis/St. Paul area in Minnesota. The new team was named after the state’s famous Twin Cities and began their inaugual season with a talented roster featuring Harmon Killebrew, Bob Allison, Camilo Pascual, and Jim Lemon. Homegrown talents Jim Kaat, Zoilo Versalles, Jimmie Hall, and Tony Oliva combined with the Twins already potent nucleus to make the team a force to be reckoned with in the 1960s. -

The Mirage of SAPA & Minor League Baseball Wages

BRUCKER (DO NOT DELETE) 11/5/2020 10:25 PM [SCREW] AMERICA’S PASTIME ACT: THE MIRAGE OF SAPA & MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL WAGES John Brucker* I. INTRODUCTION The dream of becoming a professional baseball player is an aspiration as all-American as the sport itself. And while baseball and hot dogs are a timeless duo, it is unsurprising that few young people are as enchanted by the prospect of becoming a professional hot dog vendor. Curiously, though, in all but a select few professional ballparks, the hot dog vendor actually makes more money than the ballplayer.1 Jeremy Wolf, a minor league baseball player formerly in the New York Mets organization, attests, “I was paid $45 per game . $3 [per] hour for 70 hours a week . I played in front of 8,000 people [each] night and went to bed hungry. [A]fter seven months of work, I left with less money than I started . .”2 Be that as it may, Major League Baseball (MLB), for its part, presides over this puzzling reality as puppeteer.3 Players at the MLB level earn astounding wealth; however, members of a major league team’s minor leagues—the multi-tiered system below it that employs thousands of Minor League Baseball (MiLB) players who form the lifeblood of an organization’s future—fight to pay rent and eat a decent meal, all while vying rigorously for a promotion to MLB. Because of the inherent symbiosis between MLB and MiLB, the wage disparity between the two entities defies common sense, but not logic: MLB is a business and a good one at that.