Screenwriters on Screenwriting. the BAFTA and BFI Screenwriters' Lecture Series in Association with the JJ Charitable Trust S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oscars and America 2011

AMERICA AND THE MOVIES WHAT THE ACADEMY AWARD NOMINEES FOR BEST PICTURE TELL US ABOUT OURSELVES I am glad to be here, and honored. I spent some time with Ben this summer in the exotic venues of Oxford and Cambridge, but it was on the bus ride between the two where we got to share our visions and see the similarities between the two. I am excited about what is happening here at Arizona State and look forward to seeing what comes of your efforts. I’m sure you realize the opportunity you have. And it is an opportunity to study, as Karl Barth once put it, the two Bibles. One, and in many ways the most important one is the Holy Scripture, which tells us clearly of the great story of Creation, Fall, Redemption and Consummation, the story by which all stories are measured for their truth, goodness and beauty. But the second, the book of Nature, rounds out that story, and is important, too, in its own way. Nature in its broadest sense includes everything human and finite. Among so much else, it gives us the record of humanity’s attempts to understand the reality in which God has placed us, whether that humanity understands the biblical story or not. And that is why we study the great novels, short stories and films of humankind: to see how humanity understands itself and to compare that understanding to the reality we find proclaimed in the Bible. Without those stories, we would have to go through the experiences of fallen humanity to be able to sympathize with them, and we don’t want to have to do that, unless we have a screw loose somewhere in our brain. -

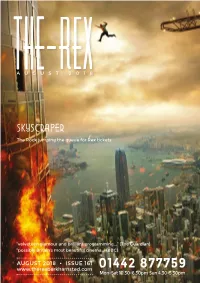

SKYSCRAPER the Rock Jumping the Queue for Rex Tickets

AUGUST 2018 SKYSCRAPER The Rock jumping the queue for Rex tickets “velveteen glamour and brilliant programming...” (The Guardian) “possibly Britain’s most beautiful cinema..” (BBC) AUGUST 2018 • ISSUE 161 www.therexberkhamsted.com 01442 877759 Mon-Sat 10.30-6.30pm Sun 4.30-5.30pm BEST IN AUGUST CONTENTS Films At A Glance 16-17 Rants & Pants 26-27 BOX OFFICE: 01442 877759 Summer 1993 Mon to Sat 10.30-6.30 From Spain, a beautifully told autobiographical story of family and belonging. The children are tiny but weirdly ‘natural actors’. Remarkable. Sun 4.30-5.30 Don’t miss. See page 11 SEAT PRICES BEST OF THE WORST Circle £9.50 Concessions/ABL £8.00 Back Row £8.00 The perfect venue for Table £11.50 Concessions/ABL £10.00 your meetings and events Royal Box Seat (Seats 6) £13.00 Whole Royal Box £73.00 Matinees - Upstairs £5, Downstairs £6.50, Royal Box £10 A unique conference venue, the perfect location for a board meeting, Swimming With Men Tag A ridiculous (true?) Full Monty tale Total All-American pap. Men being away day, or team building activities! Disabled and flat access: through of eight hapless men ‘formation children all their lives, determined the gate on High Street (right of drowning’. All the actors to win ‘tag’ at all costs. Another apartments) - 30 minutes from London drown, no stand ins. true? yarn. You will hope it’s not. - A former Royal Residence See page 11 See page 19 - 33 fully equipped meeting rooms suitable for up to 300 people Director: James Hannaway - 10 historic function rooms 01442 877999 - 190 bedrooms Advertising: Chloe Butler - Beautiful gardens ideal for team building activities 01442 877999 - Access to world class speakers through Ashridge Executive Education Artwork: Demiurge Design 01296 668739 For further information or to arrange a site inspection, The Rex please call our dedicated events team. -

The Street Divided: Shifting Identities of British Muslims in the Post-September 11 Britain in the 2004 Film Yasmin

The Street Divided: Shifting Identities of British Muslims in the Post-September 11 Britain in the 2004 Film Yasmin Senjo Nakai1 บทคัดย่อ การปรับตัวทางวัฒนธรรม (acculturation) เป็นกระบวนการที่บุคคล หรือกลุ่มบุคคลเปลี่ยนแปลงตนให้เข้ากับสภาพแวดล้อมทางวัฒนธรรมใหม่ ใน ปัจจุบันนี้โลกาภิวัตน์ได้ส่งผลให้ผู้อพยพ ผู้ลี้ภัย ชนพื้นเมืองและคนต่างด้าวเข้า มาสัมผัสกับวัฒนธรรมที่แตกต่างกันมากขึ้น และผ่านกระบวนการปรับตัวทาง วัฒนธรรม บทความนี้ได้วิเคราะห์ถึงกลยุทธ์การปรับตัวทางวัฒนธรรมที่ปรากฏ ในภาพยนตร์ของสหราชอาณาจักรที่มีชื่อว่า Yasmin (2547) ตามการจ�าแนก ประเภทการปรับตัวทางวัฒนธรรมของ John W. Berry โดยมีวัตถุประสงค์เพื่อ อธิบายว่า ภาพยนตร์เรื่องนี้แสดงถึงการเปลี่ยนอัตลักษณ์ของชาวมุสลิมในอังกฤษ อย่างไร รวมทั้งการพิจารณาความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างอัตลักษณ์กับการเมืองด้วย ภาพยนตร์เรื่อง Yasmin เป็นฉากที่เกิดในสหราชอาณาจักรก่อนและ หลังเหตุการณ์วันที่ 11 กันยายน การส�ารวจความตึงเครียดที่เกิดขึ้นหลังวันที่ 11 กันยายนจึงเป็นภาพสะท้อนผ่านดวงตาของตัวเอก Yasmin ชาวมุสลิม-อังกฤษ ผู้สืบเชื้อสายปากีสถาน Yasmin คับข้องระหว่างสองวัฒนธรรมของชุมชน ปากีสถานอพยพกับสังคมอังกฤษเสรีนิยมแต่กังวลชาวมุสลิมเพิ่มมากขึ้น ใน ภาพยนตร์เรื่องนี้ได้บรรยายถึงภาพการต่อรองเกี่ยวกับอัตลักษณ์ทางวัฒนธรรม ในชีวิตประจ�าวันของ Yasmin ระหว่างช่วงก่อนและหลังวันที่ 11 กันยายน ซึ่ง สิ่งนี้ได้เตือนให้เราระลึกว่า อัตลักษณ์ทางวัฒนธรรมไม่ได้มีสภาพคงที่ หากแต่ 1 PhD in International Communication, Lecturer of Bachelor of Arts in Journalism (BJM), Faculty of Journalism and Mass Communication, Thammasat University. เป็นกระบวนการปรับตัวอย่างต่อเนื่อง และเป็นการต่อรองระหว่างวัฒนธรรม เจ้าถิ่นกับวัฒนธรรมดั้งเดิมของบุคคลหนึ่ง -

EMMA. an Autumn De Wilde Film Running Time: 125 Minutes

EMMA. an Autumn de Wilde film Running Time: 125 minutes 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Synopsis . 3 II. A Screwball Romantic Comedy of Manners and Misunderstandings . 5 III. Casting EMMA.: Bringing Together an Electric Ensemble . 9 IV. About the Production . 16 V. Period Finery: Styling EMMA. 20 VI. Soundtrack and Score: The Music of EMMA. 23 VII. About the Cast . 27 VIII. About the Filmmakers . 39 IX. Credits . 49 2 SHORT SYNOPSIS Jane Austen’s beloved comedy about finding your equal and earning your happy ending is reimagined in this delicious new film adaptation of EMMA. Handsome, clever and rich, Emma Woodhouse is a restless “queen bee” without rivals in her sleepy little English town. In this glittering satire of social class, Emma must navigate her way through the challenges of growing up, misguided matches and romantic missteps to realize the love that has been there all along. LONG SYNOPSIS Jane Austen’s beloved comedy about finding your equal and earning your happy ending is reimagined in this delicious new film adaptation of EMMA. Handsome, clever and rich, 21-year-old Emma Woodhouse (Anya Taylor-Joy) is a restless “queen bee” who has lived all her life in the sleepy English village of Highbury with very little to distress or vex her. When our story begins, Emma has recently discovered the thrill of matchmaking. She has succeeded in orchestrating a marriage between her governess and the kind widower, Mr. Weston. Emma celebrates her success until she realizes that she has also orchestrated the loss of her only mother figure and companion in the house. -

Slumdog Millionaire: Politics of Representation and Global Culture

Slumdog Millionaire: Politics of Representation and Global Culture by Cherri Buijk A thesis presented for the B.A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Spring 2010 3 22 March Cherri Rosemarie-Anke Buijk 4 Acknowledgments My thesis advisor, Professor Megan Sweeney, provided the eyes of an astute reader as well as the patience of a kind person: she created for me the perfect intellectual environment for sounding out my sprawling, mercurial ideas. Professor Cathy Sanok’s continually clear instruction and steady encouragement in every week of each semester provided the platform from which I could imagine my own possibilities. 5 Abstract The film Slumdog Millionaire follows Jamal Malik, a young man who achieves the full prize offered on an Indian game show based on the British Who Wants to be a Millionaire?, but his origins in the slums of Mumbai convince the show's producers that his credibility is suspect. The film reveals how he knew the answer to each of the game show questions by chronicling Jamal's perspective from childhood to adulthood. Slumdog was adapted for screen by The Full Monty's Simon Beaufoy from a novel by Indian diplomat Vikas Swarup, Q&A. Slumdog is an international production, a collaboration between Hollywood and "Bollywood," India's film industry. Immediately following its release, the film received critical acclaim, but since produced a controversial discourse about the film's subject material, its representational work, its status as a cinematic production, and its political nature. In each chapter, I address those major concerns expressed in Slumdog’s critical discourse. -

Working Class in British Films 1950S-2000S : Identity, Culture, and Ideology

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2011 Working class in British films 1950s-2000s : identity, culture, and ideology. Tongyun Shi 1961- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Shi, Tongyun 1961-, "Working class in British films 1950s-2000s : identity, culture, and ideology." (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1320. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1320 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WORKING CLASS IN BRITISH FILMS 1950s-2000s: IDENTITY, CULTURE, AND IDEOLOGY By Tongyun Shi B.A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, 1984 M.A., University of Warwick, 1991 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2011 Copyright 2011 by Tongyun Shi All rights reserved WORKING CLASS IN BRITISH FILMS 1950s-2000s: IDENTITY, CULTURE, AND IDEOLOGY By Tongyun Shi B.A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, 1984 M.A., University of Warwick, 1991 A Dissertation Approved on October 14, 2011 By the following Dissertation Committee: Robert St. -

The Full Monty

AUGUST 17 - SEPTEMBER 3 PATIENT-CENTERED SERVICES @ BROOK H AVEN MEMORIAL HOSPITAL MEDICAL CENTER Our Patient-Centered Services include: • Behavioral Health • Maternal/Child Services – Access Center • Neuroscience Center Emergency treatment and referral – Focus... medical treatment • Outpatient Laboratory Services of acute withdrawal symptoms • Pain Management – Inpatient Care • Radiological Imaging Services – Outpatient Mental Health and Alcohol Treatment • Sleep Disorder Center – Psychiatric Home Care • Surgical Solutions for Weight Loss • Cardiac Rehabilitation • Women’s Imaging • Community Health Centers • Community Wellness Programs • Coumadin Management • Hemodialysis Center • Home Health Care • Hospice Physician/Dental Referral Service (800) 694-2440 BROOKHAVEN MEMORIAL HOSPITAL MEDICAL CENTER • 631-654-7100 101 HOSPITAL ROAD • PATCHOGUE, NEW YORK 11772 • www.BrookhavenHospital.org Sales Exchange Co., Inc. Jewelers and Collateral Loanbrokers Classic and Contemporary Platinum and Gold Jewelry designs that will excite your senses. One East Main St., Patchogue 631.289.9899 www.wmjoneills.com Mention this ad for 10% discount on purchase Specialists in Family Owned & Quality & Service Operated Since 1976 1135 Montauk Hwy., Mastic • 399-1890/653-RUGS 721 Rte. 25A (next to Personal Fitness), Rocky Point • 631-744-1810 Open 7 Days We love it when you love what you’re walking on. The Pine Grove Inn has served generations of guests since its establishment in 1910. Our seasonal menus emphasize prime beef, fresh local seafood and Long Island produce as well as the traditional German fare which made us famous. The Palm Bar in the Pavilion Room overlooking the Swan River is a popular meeting place for lunch, dinner, or simply a relaxing cocktail and features live entertainment Thursday through Sunday. -

Complete List of DVD and Blu-Ray Movies

List of Movies and TV Shows in the Library Collection Title Type 10,000 B.C. [bluraydisc] The 100. The complete first season [videodisc] The 100. The complete second season [videodisc] The 100. The complete third season [videodisc] The 100 year-old man who climbed out the window and disappeared [videodisc] The 10th kingdom [videodisc] 11.22.63 [videodisc] 12 angry men [videodisc] 12 strong [bluraydisc] 12 strong [videodisc] 12 years a slave. [bluraydisc] 12 years a slave [videodisc] 127 hours [videodisc] 13 assassins [videodisc] 13 hours : the secret soldiers of Benghazi [videodisc] 13 Rue Madeleine [videodisc] 1408 [videodisc] The 15:17 to Paris [bluraydisc] The 15:17 to Paris [videodisc] 15 minutes [videodisc] 16 and pregnant [videodisc] 16 and pregnant : the first season. [videodisc] 2 days in New York [videodisc] 2 fast 2 furious [videodisc] 2001 a space odyssey / [videodisc] 2012 [bluraydisc] 2012 [videodisc] 20th century women [videodisc] 21 grams [videodisc] 21 Jump Street [videodisc] 22 Jump Street [videodisc] 24. [videodisc] 24. [videodisc] 24. Season five [videodisc] 24. [videodisc] 24. [videodisc] 24. Season seven [videodisc] 24. Season six [videodisc] 24. [videodisc] Jul 11, 2018 - 1 - 10:00:03 AM List of Movies and TV Shows in the Library Collection Title Type 24. [videodisc] 25th hour [videodisc] 27 dresses [videodisc] 28 days later [videodisc] 3:10 to Yuma [videodisc] 300 rise of an empire / [bluraydisc] 300 rise of an empire / [videodisc] The 33 [videodisc] 360 [videodisc] The 39 steps [videodisc] 4 film favorites. [videodisc] 4 months, 3 weeks & 2 days [videodisc] 42 [bluraydisc] 42 : the Jackie Robinson story / [videodisc] 42nd Street [videodisc] 47 Ronin [videodisc] 5 flights up [bluraydisc] 5 flights up [videodisc] 50 first dates [videodisc] 50 Sci-fi classics over 62 hours. -

British Muslims After 9/11 in Yasmin (2004)

Claudia Sternberg Babylon North: British Muslims after 9/11 in Yasmin (2004) This contribution offers a reading of the film Yasmin which tells the story of the impact the events of 9/11 and their aftermath have on a young British Pakistani woman, her family and community in northern England. The paper analyses the narrative’s juxtaposition of the main characters’ translocal existence with the global discourses of terrorism and Islamism as well as the title character’s struggle to re-evaluate and re-assert her identity as a Muslim woman in the wake of increasing Islamophobia. Furthermore, it discusses the filmmakers’ ethnographic approach to their subject-matter and the significance of an unstaged scene highlighted by mainstream reviewers. Finally, it is argued that Yasmin – despite its temporal and geographical specificity – continues and recodes a previously established narrative tradition of social exclusion and racist policing which is more closely connected with black British cinema of the 1970s and 1980s than with Asian British films of the 1990s and 2000s. 1. Background and Production Context In the 1990s and 2000s, a number of Asian-themed feature films were made by white and/or Asian British writers and directors; most of them – including the popular East is East (1999, dir. Damien O’Donnell) and Bend It Like Beckham (2002, dir. Gurinder Chadha), but also the lesser known debut features Bollywood Queen (2002, dir. Jeremy Wooding), Halal Harry (2006, dir. Russell Razzaque) and Nina’s Heavenly Delights (2006, dir. Pratibha Parmar) – can be classed as dramatic comedies. Within this genre, secular lifestyles and indulgence in popular culture – Western or Eastern – are presented as positive and liberating and conflict is resolved through humour and compromise. -

The Full Monty 4

Penguin Readers Factsheets level E Teacher’s notes 1 2 3 The Full Monty 4 by Wendy Holden 5 Based on the screenplay by Simon Beaufoy 6 INTERMEDIATE SUMMARY he Full Monty is the novelization of a very popular BACKGROUND AND THEMES T film which was released in 1997. The story takes place in Sheffield, an industrial town in the north of England, in the early 1980s. As in many towns in Britain at ‘The Full Monty’ is set in the early 1980s. Gaz, the central that time, the town has far fewer jobs available in heavy character of the film, has been unemployed for three industry then it did in the past. Factories making steel years. He gets some money to live on from the state. This used to employ the men of the town. Now the factories used to be called ‘unemployment benefit’ and is now employ fewer men and many men stay at home. There is called the ‘job-seekers allowance’. Most people call it ‘the work for the women in the new companies which have dole’ - Gaz is on the dole. Gaz is also separated from his started up, but less work for the men. wife - she left him two years ago - and they have one son. THE FULL MONTY By law he has to pay money every week to Nathan’s The story opens with Gaz and Dave, two friends, mother to help support him - to pay for Nathan’s food and stealing a piece of iron from their old factory. Gaz thinks clothes. Because Gaz is on the dole, the amount he has they can sell it for a few pounds. -

Simon Beaufoy Interview - Big Issue Kate Wellham

Simon Beaufoy interview - Big Issue Kate Wellham It’s only to be expected that screenwriter Simon 'Slumdog Millionaire' Beaufoy should have all the right lines, and he dutifully trots them when Big Issue in the North catches up with him at this year’s Bradford International Festival. He tells us he loves India; he's not interested in money; Yorkshire will always inspire his work, and so on. It's all so easy to say, now that he's written the Oscar-winning screenplay for yet another internationally-successful film. But even with a writer as successful as Beaufoy, actions speak louder than words. For a start, it's remarkable that Simon should return as a guest to this festival in the first place, when it would be easy to decline, claiming a busy schedule, exhaustion or family time after months on the awards trail. In fact, not only does he return, but he does so as the festival’s new patron - an invaluable endorsement to his craft in the city he grew up in - even stepping up to do an impromptu screentalk for the audience at Slumdog’s screening. But, most telling of all, he brings his new little gold friend with him to Bradford. “It's not even in a protective case or anything”, whispers a member of staff at festival venue the National Media Museum. In fact, he happily hands his Oscar to anyone who asks (and even a few who don't), posing with audience members after the screentalk until everyone has a picture. “Everyone wants to pick it up, then they go 'wow, it's heavy', and then they smile,” says Simon. -

The Full Monty

The Full Monty WENDY HOLDEN Based on the screenplay by SIMON BEAUFOY Level 4 Retold by Anne Collins Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter 1 Pearson Education limited Contents Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. page ISBN-13: 978-0-582-41981-0 Introduction iv ISBN-10: 0-582-41981-6 Chapter 1 The Chippendales Come to Sheffield 1 First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 1998 This edition first published 1999 Chapter 2 At the Job Club 7 9 10 8 Chapter 3 Lomper 12 Copyright ©Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation 1998, 1999 Chapter 4 Finding a Dance Teacher 21 Cover art and photographs courtesy of Fox Searchlight All rights reserved Chapter 5 Horse and Guy Join the Group 27 Chapter 6 Becoming Good Friends 32 Typeset by Digital Type, London Set in 11/13ptBembo Chapter 7 Gaz Says the Wrong Thing 38 Printed in China SWTC/08 Chapter 8 Dave Changes His Mind 47 Chapter 9 In Trouble with the Police 50 Alt rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, Chapter 10 Problems 57 electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. Chapter 11 The Full Monty 61 Activities 71 Published by Pearson Education Limited in association with Penguin Books Ltd, both companies being subsidiaries of Pearson Plc For a complete list of titles available in the Penguin Readers series, please write to your local Pearson Education office or to: Penguin Readers Marketing Department, Pearson Education, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE.