Colloquium Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IBM Bladecenter S Types 7779 and 8886 12-Disk Storage Module

IBM BladeCenter S Types 7779 and 8886 12-Disk Storage Module IBM BladeCenter S Types 7779 and 8886 12-Disk Storage Module Note Note: Before using this information and the product it supports, read the general information in Notices; and read the IBM Safety Information and the IBM Systems Environmental Notices and User Guide on the IBM Documentation CD. First Edition (July 2013) © Copyright IBM Corporation 2013. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents Chapter 1. BladeCenter S Types 7779 Electronic emission notices .........14 and 8886 disk storage module .....1 Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Disk storage modules ...........1 statement ..............14 Industry Canada Class A emission compliance Chapter 2. Installation guidelines ....3 statement ..............15 Avis de conformité à la réglementation System reliability guidelines .........3 d'Industrie Canada ...........15 Handling static-sensitive devices........4 Australia and New Zealand Class A statement . 15 European Union EMC Directive conformance Chapter 3. Installing a disk storage statement ..............15 module ...............5 Germany Class A statement ........15 Japan VCCI Class A statement .......16 Chapter 4. Removing a disk storage Japan Electronics and Information Technology module ...............7 Industries Association (JEITA) statement....17 Japan Electronics and Information Technology Industries Association (JEITA) statement....17 Chapter 5. Replacing 6-Disk Storage -

HPE D2220sb Storage Blade Overview

QuickSpecs HPE D2220sb Storage Blade Overview HPE D2220sb Storage Blade Do you need a direct attached or shared storage solution within your BladeSystem enclosure? Direct attached storage The D2220sb Storage Blade delivers direct attached storage for c-Class Gen9 blade servers, with support for up to twelve hot plug small form factor (SFF) SAS or SATA hard disk drives or SAS/SATA SSDs. The enclosure backplane provides a PCI Express connection to the adjacent c-Class server blade and enables high performance storage access without any additional cables. The D2220sb Storage Blade features an onboard Smart Array P420i controller with 2GB flash-backed write cache, for increased performance and data protection. Up to eight D2220sb storage devices can be supported in a single BladeSystem c7000 enclosure. Two ways to create shared storage with the D2220sb Use HPE StoreVirtual VSA software to turn the D2220sb into an iSCSI SAN for use by all servers in the enclosure and any server on the network. HPE StoreVirtual VSA software is installed in a virtual machine on a VMware ESX host server adjacent to the D2220sb. HPE StoreVirtual VSA turns the D2220sb into a scalable and robust iSCSI SAN, featuring storage clustering for scalability, Network RAID for storage failover, thin provisioning, snapshots, remote replication, and cloning. Expand capacity within the same enclosure or to other BladeSystem enclosures by adding additional D2220sb Storage Blades and HPE VSA licenses. A cost effective bundle of the D2220sb Storage Blade and a HPE StoreVirtual VSA license makes purchasing convenient. If storage needs increase, add HPE P4300 or P4500 systems externally and manage everything via a single pane of glass. -

IBM Bladecenter HS22

Versatile, easy-to-use blade optimized for performance, energy and cooling Product Guide August 2010 IBM BladeCenter HS22 Product Overview No-compromise, truly balanced, 2-socket blade server for infrastructure, virtualization and enterprise business applications Suggested uses: Front-end and mid-tier applications requiring high performance, enterprise- class availability and extreme flexibility and power efficiency. CONTENTS Today’s data center environment is tougher than ever. You’re looking to reduce IT cost, complexity, space requirements, energy consumption and heat output, while increasing Product Overview 1 flexibility, utilization and manageability. Incorporating IBM X-Architecture ™ features, the IBM ® BladeCenter ® HS22 blade server, combined with the various BladeCenter chassis, can help Selling Features 2 you accomplish all of these goals. Key Features 4 Reducing an entire server into as little as .5U of rack space (i.e., up to 14 servers in 7U) does Key Options 14 not mean trading away features and capabilities for smaller size. Each HS22 blade server offers features comparable to many 1U rack-optimized full-featured servers: The HS22 supports up to HS22 Images 15 two of the latest high-performance or low-voltage 6-core , 4-core , and 2-core Intel® Xeon ® 5500 series and 5600 series processors.. The Xeon processors are designed with up to 12MB of HS22 Specifications 16 shared cache and leading-edge memory performance (up to 1333MHz , depending on The Bottom Line 18 processor model) to help provide the computing power you require to match your business needs and growth . The HS22 supports up to 192GB of registered double data rate III ( DDR3 ) Server Comparison 19 ECC (Error Checking and Correcting) memory in 12 DIMM slots, with optional Chipkill ™ protection 1, for high performance and reliability. -

Organizations Turn to Blade Servers to Boost Power, Save Space and Cut Costs

Blade Servers Cut Paths Organizations turn to blade servers to boost power, save space and cut costs. 62 • Blade Servers to Progress In government agencies and educational institutions, few research firm. “They want to leverage industry-standard, low- challenges loom as large as managing information-technology cost servers, yet be able to maintain high availability while resources. Organizations that lack adequate computing achieving high performance. Clustering and virtualization power often find that it is impossible to manage mountains of technologies achieve these goals by using resources more efficiently and effectively.” information. Yet, those who throw technology at every problem often wind up creating an unmanageable and expensive IT As a result, many organizations are turning to blade servers. These units, which consist of multiple server cards enclosed environment — particularly when numerous applications and in a specialized chassis, offer a more efficient architecture servers enter the picture. for managing multiple applications, databases and storage hese days, things aren’t getting any simpler — devices. Blades — consisting of several servers within a single especially as the demand for information technology chassis — are rapidly moving into the mainstream. In the Tgrows and more sophisticated data requirements process, they are replacing more expensive and complicated take hold. “Organizations are looking for ways to optimize mid-range and mainframe computers. their computing environments without spending a great deal IMEX Research reports that sales of blade servers grew more money,” observes Anil Vasudeva, president of IMEX from near zero in 2001 to about $2.2 billion in 2005. At Research, a San Jose, Calif.-based IT consulting and market present, about 7 percent of servers used are blades, but the 4 Blade Servers • 63 figure is expected to hit 32 percent by 2009. -

HP Storage Blade Family

Data sheet Meet growing storage needs for your blade servers HP Storage Blade family HP IO Accelerator for HP D2200sb HP StoreEasy 3830 HP LTO Ultrium BladeSystem c-Class Storage Blade Gateway Storage Blade Tape Blades Now that you have realized the substantial HP BladeSystem integrates storage and benefits of owning an HP BladeSystem, data protection look to HP for your storage and data You have deployed an HP BladeSystem c-Class solution and successfully removed the barriers often found in “racked, stacked, protection needs. Easily integrate internal and wired” data centers. Now you are looking at storage products storage blades into HP BladeSystem and solutions that can meet your IT and business needs. c-Class enclosures and further expand We provide a portfolio of direct attached, NAS, iSCSI, SAN, tape, and external storage solutions for HP BladeSystem, encompassing all your your external storage capacity using your storage requirements. Configure up to 43.2 TB SAS or 48 TB SATA of shared storage in a HP BladeSystem c3000 enclosure or 86.4 TB SAS existing NAS or SAN deployments. The or 96 TB SATA of shared storage in a HP BladeSystem c7000 enclosure. broad portfolio of solutions from HP is designed to address specific storage challenges of organizations, regardless of its size. HP IO Accelerator for BladeSystem c-Class Is your business facing constant bottlenecks in application quickly and return to full performance, without the penalty of performance? Are you concerned about real-time data access? delays associated with waiting for a disk to spin back up • Implementing HP IO Accelerator SSD’s lower average power HP IO Accelerator for BladeSystem c-Class is part of a comprehensive consumption reduces the demands on the data center to solid state storage portfolio from HP. -

Ready-To-Go Solutions for High-Performance Computing Fujitsu and High-Performance Computing a Success Story for More Than 30 Years

Ready-to-Go Solutions for High-Performance Computing Fujitsu and High-Performance Computing A success story for more than 30 years Today Fujitsu is the most experienced and largest provider of HPC A complete stack of x86 PRIMERGY server-based high-performance solutions in the Asian market, and has been a leading HPC vendor in computing solutions enable engineers and scientists to conduct Europe almost from the beginning, offering customers the know-how their research and development projects very efficiently, without having it has gained from installing more than 1,200 HPC systems. to acquire the specialized expertise needed to set up and operate complex HPC platforms. The stack is comprised of server and storage Fujitsu responds to the rapidly growing demand for high-performance platforms, HPC middleware and integration services. To address the computing with intelligent solutions that deliver top performance growing needs of small and medium-sized enterprises, Fujitsu tailored to meet today‘s HPC requirements. Furthermore, these solutions provides integrated and certified ready-to-go HPC cluster solutions already offer the scalability that will be needed to meet the increasing that are optimized for specific business requirements. The developments that have taken place in high-performance computing (HPC) performance demands of the future. over the decades can be described quite simply: Without Fujitsu research, the development of the supercomputer would have been quite different. In the 1970s Fujitsu collaborated with its customers to fulfill many of mankind‘s Fujitsu milestones in developing supercomputers for more than three decades dreams – in aerospace technology, meteorology and astronomy, environment and energy, or in various other fields of enterprise research. -

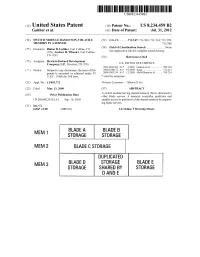

Blade a Blade B Mem 1 Storage Storage Duplicated

US008234459B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent N0.: US 8,234,459 B2 Gaither et a]. 45 Date of Patent: Jul. 31 a 2012 (54) SWITCH MODULE BASED NON-VOLATILE (52) US. Cl. ...... .. 711/147; 711/103; 711/114; 711/170; MEMORY IN A SERVER 711/202 (75) Inventors: Blaine D- Gaither’ Fort Collins’ CO (58) Field 0f.Cla'ss1?cat10n Search ............. ..: ...... .. None (Us); Andrew R- Wheeler’ Fort Collins’ See appl1cat1on ?le for complete search h1story. CO (Us) (56) References Cited (73) Assignee: Hewlett-Packard Development Company, L.P., Houston, TX (US) US‘ PATENT DOCUMENTS 2003/0033363 A1* 2/2003 Garnett et a1. .............. .. 709/203 ( * ) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term ofthis Zoos/0244172 A1: 10/2008 Kan°_ ~~_ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~~ 711/112 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 2008/0301256 A1 12/2008 McWllllams et a1. ...... .. 709/214 U.S.C. 154(b) by 568 days. * cited by examiner (21) Appl. No.: 12/403,712 Primary Examiner * ShaWn X Gu (22) Filed: Mar. 13, 2009 (57) ABSTRACT . A sWitch module having shared memory that is allocated to (65) Pnor Pubhcatlon Data other blade servers. A memory controller partitions and US 2010/0235562 A1 Sep. 16, 2010 enables access to partitions of the shared memory by request ing blade servers. (51) Int. Cl. G06F 12/00 (2006.01) 14 Claims, 5 Drawing Sheets BLADE A BLADE B MEM 1 STORAGE STORAGE MEM 2 BLADE C STORAGE DUPLICATED MEM 3 BLADE n STORAGE BLADE E STORAGE SHARED BY STORAGE D AND E US. Patent Jul. 31, 2012 Sheet 2 of5 US 8,234,459 B2 ROM ~Z°4 / 201~ PROCESSOR 4 , RAM ~203 A V SWITCH 1 > V0 N210 00~ MODULE FIG. -

Cisco UCS 5100 Series Blade Server Chassis Data Sheet

Data Sheet Cisco UCS 5100 Series Blade Server Chassis Cisco Unified Computing System Overview The Cisco Unified Computing System™ (Cisco UCS®) is a next-generation data center platform that unites computing, networking, storage access, and virtualization resources into a cohesive system designed to reduce Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) and increase business agility. The system integrates a low-latency, lossless 10/40 Gigabit Ethernet unified network fabric with enterprise-class, x86-architecture servers. The system is an integrated, scalable, multichassis platform in which all resources participate in a unified management domain (Figure 1). Figure 1. The Cisco Unified Computing System Is a Highly Available Cohesive Architecture With the Cisco UCS 6324 Fabric Interconnect, the management flexibility and cable reduction of the full-scale Cisco UCS solution is now available in a single-chassis implementation. The Cisco UCS 6324 Fabric Interconnect © 2017 Cisco and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. This document is Cisco Public Information. Page 1 of 5 allows a single Cisco UCS chassis to be managed and configured in the same way as a full-scale Cisco UCS solution, providing the advantages of Cisco UCS to smaller businesses and remote sites. Product Overview The Cisco UCS 5100 Series Blade Server Chassis is a crucial building block of the Cisco Unified Computing System, delivering a scalable and flexible blade server chassis for today’s and tomorrow’s data center while helping reduce TCO. The Cisco UCS 5108 Blade Server Chassis (Figure 2) is six Rack Units (6RU) high and can mount in an industry- standard 19-inch rack. A chassis can house up to eight half-width Cisco UCS B-Series Blade Servers and can accommodate both half-width and full-width blade form factors. -

ATCA Server Systems for Telecommunications Services

ATCA Server Systems for Telecommunications Services Hiroya Kawasaki Shoichi Matsuoka Atsuhiro Makino Yoshihisa Ono Internet protocol (IP) networks have evolved to provide higher speed and greater bandwidth more safely and economically and will provide the foundations for a wide diversity of services in the future. A key consideration in the construction of new systems is to enable these new services to be deployed rapidly while at the same time ensuring that networks expand smoothly and remain compatible with inherited assets. The PICMG3.0 Advanced Telecom Computing Architecture (ATCA) is an international open standard that was primarily established to respond to the needs of telecommunications carriers. Fujitsu provides hardware and middleware products that comply with this specification as a platform for the construction of future IP network services, starting with the UB300 series of network service infrastructure products, and has already put them to use in commercial systems. This paper introduces the latest ATCA-compliant model, focusing on the hardware platform provided by Fujitsu. 1. Introduction economically. The growth of the Internet and the This paper introduces the basic hardware emergence of new services such as video services specifications of Fujitsu’s line-up of ATCA systems are causing an explosive increase in traffic on and describes the hardware configuration of the the Internet and mobile networks. Keeping up latest model (ATCA-S2) and the features of each with these trends requires faster processing product. speeds in the upper layers, increased network speed and capacity, and the ability to construct 2. Hardware features of ATCA service applications quickly and economically. servers To support these developments, a new platform Fujitsu’s ATCA server system products is needed. -

The Role of PCI Express® in Wired Communications Systems

® WHITE PAPER The Role of PCI Express® in Wired Communications Systems By Ian Dobson, Principal System Architect, CTO Offi ce PCI Express® (PCIe®), the latest generation in the PCI family of protocols, is backed by an extensive ecosystem and offers designers a high-performance, general-purpose, industry-standard interconnect at relatively low cost. Those inherent advantages are already driving its rapid adoption in the PC, server, and storage markets. Like its predecessors in the family, PCIe will inevitably fi nd wide use in communications systems as well. This paper will look at some of the potential applications for this popular industry-standard interconnect in the wired communications infrastructure. It will begin by examining the various tiers of the network hierarchy and how their particular data fl ow requirements differ. Next, it will review the PCI interconnect family and the new capabilities PCIe brings to the specifi cation. Building on those observations, the paper will outline some of the likely applications for PCIe in the network landscape, such as in on-card control planes and central processing architectures. Finally, it will explore how the new capabilities embedded in PCIe open the door to new, less apparent applications in wireline communications equipment, such as in control planes between intelligent cards and between system shelves. The network view Wire-line communications equipment is designed to match the requirements of the market segment it addresses and where it sits in the network hierarchy. Figure 1 provides a simplifi ed view of network topology with end users at the right and bottom of the fi gure and the “deeper” tiers of the network to the top and left of the fi gure. -

Dell 8/4Gb/S Fibre Channel Pass-Through Module for Dell Poweredge™ M1000e Blade Servers

DATASHEET CONNECTIVITY Dell 8/4Gb/s Fibre Channel Pass-Through Module for Dell PowerEdge™ M1000e Blade Servers SUPERIOR Interoperability without Consideration The Dell 8/4Gb/s Fibre Channel Pass-Through INTEROPERABILITY Key Benefits Module provides superior interoperability for n Certified interoperability into Cisco or Brocade WITH CISCO connecting Dell M-Series blades into Fibre Channel Fibre Channel Storage Area Network (SAN) fabrics Storage Area Networks (SANs) from any provider. AND BROCADE Pass-Through modules are transparent devices, n Plug and Done—no setup, configuration or SAN FABRICS, unseen in SAN topologies and not consuming fabric management necessary management nodes, with the purpose to provide n PLUG AND DONE Maximum Fibre Channel SAN I/O bandwidth— direct Fibre Channel connectivity to server blades. each physical server has its own dedicated and SIMPLICITY, This makes for superior interoperability when isolated 8Gb/s Fibre Channel SAN connection integrating server blades into Cisco or Brocade MAXIMUM n Complete solution—ships with all 32-ports Fibre Channel SAN fabrics in order to maintain your enabled and 16 optical SFPs preinstalled BANDWIDTH preferred SAN equipment supplier environment. n Option to install in pairs for redundancy and high availability Plug and Done The Dell 8/4Gb/s Fibre Channel Pass-Though Module is an unmanaged device, so no setup, Key Features configuration or management is required. Simply n 32 Fibre Channel ports at 8, 4 or 2Gb/s— plug the unit into the PE M1000e Blade Server total bandwidth 512Gb/s chassis and connect cables into the pre-installed n 16 internal (server) ports and 16 external short-wave optical SFPs and you’re done. -

MIC-3042 Power Supply (CT Bus Or PICMG 2.16)

4U CompactPCI® Enclosure with cPCI MIC-3042 Power Supply (CT Bus or PICMG 2.16) Features . 8-slot 6U CompactPCI® backplane . AC cPCI 500 W + 250 W redundant (2+1) power supplies . PICMG 2.16 (CompactPCI Packet Switching Backplane) compliance . PICMG 2.5 (CompactPCI Computer Telephony) compliance . Built-in alarm module (MIC-3924L-AE) RoHS COMPLIANT 2002/95/EC Introduction The MIC-3042 is a 4U enclosure designed for standard cPCI power supplies. It is equipped with a cPCI 500 W redundant 2+1 power supply with hot-swap support. The system has 8 slots for CompactPCI boards and 6 slots for IEEE 1101.11 rear I/O transition boards. The MIC-3042 comes with a built-in high quality backplane that supports 64-bit / 66 MHz PCI cards. The standard configuration includes a H.110 CT Bus that complies with PICMG 2.5, which is the open architecture used to build telecom solutions. Specifications MIC-3042A MIC-3042B System x 1, Peripheral x 6, Switch x 1, Rear System x 1, Peripheral x 6, Media x 1, Rear 6U slot transition x 8 (80 mm, IEEE1101.11 compliant) transition x 7 (80 mm, IEEE1101.11 compliant) Blade Server Support Yes - Backplane Bus Up to 64-bit/66 MHz PCI bus H.110 CT Bus Yes Yes V (I/O) +3.3 V/+5 V (selectable) Cooling Fan 2 (front: 193 CFM, rear: 61.3 CFM) Input AC 100 ~ 254 V @ 50 ~ 60 Hz, full range (MIC-3042X-A) Output AC cPCI 250 W redundant power module Power Supply +3.3 V +5 V +12 V -12 V Max.