Race and Gender in Electronic Media Content, Context, Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lonely Soldiers: Women at War in Iraq a Regional Premiere by Helen Benedict March 16 – April 6, 2014

Play Guide Lonely Soldiers: Women at War in Iraq A regional premiere by Helen Benedict March 16 – April 6, 2014 1 History Theatre 30 East Tenth Street Saint Paul, MN 55101 Box Office: 651.292.4323 Group Sales: 651.292.4320 www.HistoryTheatre.com Table of Contents Summary of the Play* ............................................................................................ 3 About the author – Helen Benedict* ...................................................................... 3 The World of the Play: Military Ranks and Organization ....................................... 4 The World of the Play: Women in the Military* ...................................................... 5 Timeline of Women in the Military .......................................................................... 6 Sexual Assault in the Military* ................................................................................ 9 Activities • Small Group Discussion / Classroom Discussion .................................... 12 • What is Sexual Harassment? ................................................................... 13 • Sexual Harassment .................................................................................. 14 • Sexual Harassment vs. Flirting................................................................. 16 For Further Research and Suggested Reading* ................................................. 18 Help Lines, Websites, and Resources ................................................................. 20 *Material provided by Laura Weber. Play -

Are We Green Yet? Sustainability Takes Root in Our Intellectual Culture P

University Magazine Spring 2015 ST.LAWRENCE Are We Green Yet? SUSTAINABILITY TAKES ROOT IN OUR INTELLECTUAL CULTURE P. 16 ST. LAWRENCE UNIVERSITY | SPRING 2015 Spring,15 Features Nowadays, when we ask ourselves “Are We Green Yet?” we’re 16 talking about a lot more than just energy consumption. SLU Connect-DC may be “One Small Step Inside the Beltway” 24 for our students, but we’re betting it will lead to many giant leaps. As her graduation looms, a stellar student-athlete probes what makes 26 her think “There’s Something About This Place.” He’s an actor, a philanthropist and a distinguished Laurentian. 30 That’s what we say when “Introducing Kirk Douglas Hall.” Departments In Every Issue 4 On Campus 2 A Word from the President You might say these are 12 Sports 3 Letters St. Lawrence’s representatives in Congress. They’re the 32 Philanthropy in Action 41 First-Person students who participated in 37 Laurentian Portraits 42 Class Notes the University’s inaugural SLU 40 On Social Media 81 From the Archives Connect-DC program in January. One of them, Mariah Dignan ’15, On the Cover: Sustainability at St. Lawrence is a work in progress, and illustrator Edmon de Haro far right, tells us more on page JEFF MAURITZEN © demonstrates that it’s becoming part of our cerebral DNA—as well as part of our pipes and groundskeeping. 24. And if what she predicts : Above: Alexander Kusak ’12 captured this shot of a trio of Denmark Program students in Copenhagen. proves true, you may see her SITE Margot Nitschke ’16, center, describes how Denmark incorporates sustainability into its national life; page 20. -

The Fast Track Initiative

– FILMMAKER KIRBY DICK The California Endowment believes there are many opportunities for grantmakers to use communications to shift CASE STUDY THE their program work into high gear. The Fast Track Initiative seeks to identify and share examples that use media and FAST TRACK communications grantmaking to create a more receptive environment for dialogue about potential solutions, build “WE MADE THE FILM TO HELP CHANGE POLICY.” INITIATIVE public will and generate political will for policy change. We invite you to share your experiences and best practices. INTEGRATION REPETITION 10 Elements of Success Among the Fast Track case studies, we’ve identifi ed for POLICY CHANGE AGILITY ORIGINS THE INVISIBLE WAR POLICY the following 10 insights. The most critical elements of success for each case appear as THE FAST TRACK The Fledgling Fund believes that well-made process and as a result of Dick and Ziering’s pitch symbols throughout the series. documentary films can serve as a catalyst to change to a roundtable of Good Pitch attendees, the Fund minds, encourage viewers to alter entrenched provided $25,000 to fund initial outreach for Issue Sexual assault in the military goes under reported and under prosecuted as a crime. Women assaulted behaviors, and start, inform or reenergize social The Invisible War, and a subsequent $60,000 for 1 SOLUTIONS 6 PAID ADVERTISING during service have a higher PTSD rate than men in combat. movements. It has particular faith in films with additional outreach and a social media campaign. The majority of these initiatives contained messages not Having the ability to control the content and timing of Strategy Focused communications strategy for policymaker education integrated into the production process for just about the problem, but about a range of potential messages through paid advertising can create awareness a compelling narrative and an outreach plan. -

Sundance Institute Launches New Initiative to Support Inventive Artistic Practice in Nonfiction Film

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: January 18, 2016 Chalena Cadenas 310.360.1981 [email protected] Sundance Institute Launches New Initiative to Support Inventive Artistic Practice in Nonfiction Film Robert Greene, Margaret Brown, Omar Mullick and Bassam Tariq Selected as First ‘Art of Nonfiction’ Fellows Los Angeles, CA — Sundance Institute, one of the world’s largest grantmakers to documentary film, today announced the ‘Art of Nonfiction’ initiative, which will expand the Institute’s existing support for documentaries exploring contemporary social issues to include targeted creative and financial support for documentary filmmakers exploring inventive artistic practice in story, craft and form. As part of the initiative, the Institute has selected Robert Greene (Kate Plays Christine), Margaret Brown (The Order of Myths), and Omar Mullick and Bassam Tariq (These Birds Walk) as the first Art of Nonfiction fellows. The initiative launches with editorial and financial support from Cinereach. The Art of Nonfiction includes both a Fellowship for filmmakers and resources to help them build sustainable creative practices. Tabitha Jackson, Director of the Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program, developed this initiative in response to the lack of support for many exciting artists working today who take a bold, inventive cinematic approach to their documentary work (The Act of Killing, Man on Wire, 20,000 Days on Earth, Leviathan) as well as those pushing the boundaries of the form with elements including -

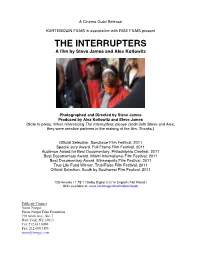

THE INTERRUPTERS a Film by Steve James and Alex Kotlowitz

A Cinema Guild Release KARTEMQUIN FILMS in association with RISE FILMS present THE INTERRUPTERS A film by Steve James and Alex Kotlowitz Photographed and Directed by Steve James Produced by Alex Kotlowitz and Steve James (Note to press: When referencing The Interrupters, please credit both Steve and Alex; they were creative partners in the making of the film. Thanks.) Official Selection, Sundance Film Festival, 2011 Special Jury Award, Full Frame Film Festival, 2011 Audience Award for Best Documentary, Philadelphia Cinefest, 2011 Best Documentary Award, Miami International Film Festival, 2011 Best Documentary Award, Minneapolis Film Festival, 2011 True Life Fund Winner, True/False Film Festival, 2011 Official Selection, South by Southwest Film Festival, 2011 125 minutes / 1.78:1 / Dolby Digital 2.0 / In English / Not Rated / Stills available at: www.cinemaguild.com/downloads Publicity Contact Susan Norget Susan Norget Film Promotion 198 Sixth Ave., Ste. 1 New York, NY 10013 Tel: 212.431.0090 Fax: 212.680.3181 [email protected] SYNOPSIS THE INTERRUPTERS tells the moving and surprising story of three dedicated individuals who try to protect their Chicago communities from the violence they, themselves once employed. These “violence interrupters” (their job title) – who have credibility on the street because of their own personal histories – intervene in conflicts before the incidents explode into violence. Their work and their insights are informed by their own journeys, which, as each of them point out, defy easy characterization. Shot over the course of a year out of Kartemquin Films, THE INTERRUPTERS captures a period in Chicago when it became a national symbol for the violence in our cities. -

AIM Bulletin #7

AIM Bulletin #7 Hark! Here's our monthly roundup, keeping you up-to-speed on breaking media impact tools, methods and debates. Catch the latest: How do you tell digital stories for maximum social impact? What has WNYC learned about making collaborations hit home? Do youth media projects make a lasting difference in the lives of participants? Find out in recent reports from the Rockefeller, Revson and McCormick foundations in our AIM Research section. Has social media now become mandatory for journalists? See how frustrated readers have begun foiling the clickbait masters, and what happened when NPR swapped out their Twitter bot for a real live human in our AIM Articles section. Questions, or suggestions for coverage? Contact Jessica Clark. Explore how documentaries make a measurable difference: On June 3, we celebrated the winners of our first annual Media Impact Festival at the National Geographic Museum in Washington, DC. The festival recognizes the role that documentary film campaigns play in informing and mobilizing audiences, activists, and policymakers. The Invisible War received this year's Henry Hampton Award for Excellence in Film and Digital Media, presented by Elizabeth Christopherson of the Rita Allen Foundation. Media Impact Funders Executive Director Vince Stehle, Invisible War Producer Amy Ziering, and Rita Allen Foundation President/CEO Elizabeth Christopherson The Ford Foundation received the Woodward A. Wickham Award for Excellence in Media Philanthropy for their support of American Promise, presented by Kathy Im of -

Calling All Filmmakers! Documentary Film As Philanthropic Strategy

| PHILANTHROPY & WEALTH PLANNING Calling All Filmmakers! Documentary Film as Philanthropic Strategy By Jacki Zehner, Chief Engagement Officer and Trustee Women Moving Millions love the movies. A night at the cinema with a bag of Developing a Philanthropic Strategy popcorn is a good night out as far as I’m concerned, but A philanthropic strategy not only provides the decision-mak- my love of film goes further than that. It is a key com- I ing framework for efficient giving, but also allows donors ponent of my philanthropic strategy through my support the opportunity to target their particular areas of interest of independent documentary filmmakers. At first glance, and concern. An effective philanthropic strategy guides their supporting documentary films may seem like an uncon- giving based on their goals and values. A donor’s mission, ventional approach to philanthropy, but it can be a highly vision and passion should be at the strategy’s core. The next effective way to influence millions and create positive social step is to identify the organizations to partner with and sup- change. Over the years, independent documentaries have port, doing so because their goals align with yours. It is very become a crucial vehicle for informing our understanding of important to both understand the theory of change behind the world and inspiring solutions for the challenges we face. the desired outcome and how that outcome will be measured Without the vital support that philanthropy can provide, over time. This is what one might call traditional philanthropy, documentary filmmakers would not be able to produce and but increasingly, high-impact donors are looking to do more. -

CMSI Journey to the Academy Awards -- Race and Gender in a Decade of Documentary 2008-2017 (2-20-17)

! Journey to the Academy Awards: A Decade of Race & Gender in Oscar-Shortlisted Documentaries (2008-2017) PRELIMINARY KEY FINDINGS Caty Borum Chattoo, Nesima Aberra, Michele Alexander, Chandler Green1 February 2017 In the Best Documentary Feature category of the Academy Awards, 2017 is a year of firsts. For the first time, four of the five Oscar-nominated documentary directors in the category are people of color (Roger Ross Williams, for Life, Animated; Ezra Edelman, for O.J.: Made in America; Ava DuVernay, for 13th; and Raoul Peck, for I Am Not Your Negro). In fact, 2017 reveals the largest percentage of Oscar-shortlisted documentary directors of color over at least the past decade. Almost a third (29%) of this year’s 17 credited Oscar-shortlisted documentary directors (in the Best Documentary Feature category) are people of color, up from 18 percent in 2016, none in 2015, and 17 percent in 2014. The percentage of recognized women documentary directors, while an increase from last year (24 percent of recognized shortlisted directors in 2017 are women, compared to 18 percent in 2016), remains at relatively the same low level of recognition over the past decade. In 2016, as a response to widespread criticism and negative media coverage, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences welcomed a record number of new members to become part of the voting class to bestow Academy Awards: 683 film professionals (46 percent women, 41 percent people of color) were invited in.2 According to the Academy, prior to this new 2016 class, its membership was 92 percent white and 75 percent male.3 To represent the documentary category, 42 new documentary creative professionals (directors and producers) were invited as new members. -

Contemporary Advocacy Filmmaking

CONTEMPORARY ADVOCACY FILMMAKING: CAMPAIGNS FOR CHANGE by Christiana Marie Cooper A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Science and Natural History Filmmaking MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana November 2015 ©COPYRIGHT by Christiana Marie Cooper 2015 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the voices around the world that have stories to tell and need people to advocate for their cause. Their stories have inspired me and led me to choose this path. I hope to always strive to do them justice, to be a voice for change, and to be a positive part of the process. I would like to especially thank Dennis Aig for continuous support and dedication to excellence, as well as his guidance throughout the thesis process. I am also very grateful to Gianna Savoie, whose support, encouragement, enthusiasm, and inspiration helped me to get here. The work of Ian van Coller was an inspiration to me, encouraging me to follow the path of advocacy. Thank you to all three for serving on my thesis committee and pushing me to challenge myself. Special thanks to Jim and Hannah for the constant encouragement and unconditional love – you guys are my life! More special thanks to my friends and family for being a unconditional part of my life and constantly providing inspiration, to Kirsten Mull-Core and Terri Hetrick for the countless hours of hiking while debating my thesis ideas, to Matt Cooper, Kerri Anthony, and Buffy Cooper for the distractions, restoration, and friendship, to Kelly Matheson and Julia Olson for creating a space to do advocacy film work and for providing such great friendship, and to my fellow talented film colleagues, from whom I continue to learn and grow. -

THE ARMOR of LIGHT a Film by Abigail E

FORK FILMS Presents THE ARMOR OF LIGHT A Film by Abigail E. Disney 87 minutes Official Selection 2015 Tribeca Film Festival 2015 AFI DOCS 2015 Provincetown Film Festival Twitter: #ArmorOfLight FB: /ArmorTheFilm http://www.armoroflightfilm.com/ FINAL PRESS NOTES Distributor Contact: Press Contact NY/Nat’l: Press Contact D.C.: Jeff Reichert/Stephanie Palumbo Steven Beeman / Michelle Renee Tsao DiMartio Fork Films Falco Ink. PR Collaborative 25 E. 21st St. 7th Floor 250 West 49th. Suite 704 2900 M St NW Suite 200 New York, NY 10010 New York, NY 10019 Washington, D.C. 20007 (212) 782-3713 (212) 445-7100 (202) 339-9598 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Press Contact LA: Press Contact Faith & Family: Amy Grey Lesley Burbridge Dish Communications Rogers & Cowan P.O. Box 2668 8687 Melrose Ave. 7th Fl. Toluca Lake, CA 91610 Los Angeles, CA 90069 (818) 508-1000 (310) 854-8100 [email protected] [email protected] 25 east 21st street 7th floor new york, ny 10010 tel 212 782 3713 fax 212 228 5275 www.armoroflightfilm.com ABOUT THE FILM THE ARMOR OF LIGHT follows an Evangelical minister and the mother of a teenage shooting victim who ask, is it possible to be both pro-gun and pro-life? What price conscience? Abigail Disney’s directorial debut, THE ARMOR OF LIGHT, follows the journey of an Evangelical minister trying to find the courage to preach about the growing toll of gun violence in America. The film tracks Reverend Rob Schenck, anti-abortion activist and fixture on the political far right, who breaks with orthodoxy by questioning whether being pro-gun is consistent with being pro-life. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Amna Mirza 415-356-8383 X442 Amna [email protected] Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Amna Mirza 415-356-8383 x442 [email protected] Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected] For downloadable images, visit pbs.org/pressroom/ THE INVISIBLE WAR PREMIERES ON INDEPENDENT LENS ON MONDAY, MAY 13, 2013 A Searing Exposé of the Culture of Sexual Violence Within the U.S. Military, Film Helps Change Policy For Sexual Assault Investigations (San Francisco, CA) — Nominated for an Academy Award® for Best Documentary Feature, The Invisible War is a groundbreaking investigative documentary about one of America’s most shameful and best kept secrets: the epidemic of rape within the U.S. military. The film paints a startling picture of the extent of the problem; today, a female soldier in combat zones is more likely to be raped by a fellow soldier than killed by enemy fire. The Department of Defense estimates there were a staggering 19,000 sexual assaults in the military in 2011. Veterans Affairs (VA) studies have shown that one third of women seeking assistance from the VA have been sexually assaulted, and that more men than women are assaulted while in service. From the Oscar®- and Emmy®-nominated filmmaking team of director Kirby Dick and producer Amy Ziering, The Invisible War premieres on Independent Lens, hosted by Stanley Tucci, on Monday, May 13, 2013 at 10 PM ET on PBS (check local listings). Focusing on the powerfully emotional stories of rape victims, The Invisible War is a moving indictment of the systemic cover up of military sex crimes, chronicling the veteran’s struggles to rebuild their lives and fight for justice. -

Testimony on Sexual Assaults in the Military

S. HRG. 113–303 TESTIMONY ON SEXUAL ASSAULTS IN THE MILITARY HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON PERSONNEL OF THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 13, 2013 Printed for the use of the Committee on Armed Services ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 88–340 PDF WASHINGTON : 2014 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 09:13 Jun 19, 2014 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 Z:\DOCS\88340.TXT JUNE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES CARL LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman JACK REED, Rhode Island JAMES M. INHOFE, Oklahoma BILL NELSON, Florida JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama MARK UDALL, Colorado SAXBY CHAMBLISS, Georgia KAY R. HAGAN, North Carolina ROGER F. WICKER, Mississippi JOE MANCHIN III, West Virginia KELLY AYOTTE, New Hampshire JEANNE SHAHEEN, New Hampshire DEB FISCHER, Nebraska KIRSTEN E. GILLIBRAND, New York LINDSEY GRAHAM, South Carolina RICHARD BLUMENTHAL, Connecticut DAVID VITTER, Louisiana JOE DONNELLY, Indiana ROY BLUNT, Missouri MAZIE K. HIRONO, Hawaii MIKE LEE, Utah TIM KAINE, Virginia TED CRUZ, Texas ANGUS KING, Maine PETER K. LEVINE, Staff Director JOHN A. BONSELL, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON PERSONNEL KIRSTEN E. GILLIBRAND, New York, Chairman KAY R. HAGAN, North Carolina LINDSEY GRAHAM, South Carolina RICHARD BLUMENTHAL, Connecticut KELLY AYOTTE, New Hampshire MAZIE K.