Holwick, Teesdale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Parkinson & Sons

THE TEESDALE MERCURY B IR TH S, M A R R IA G E S PUBLIC NOTICES GENERAL NOTICES AND DEATHS STARTFORTH CHURCH a COMMONS REGISTRATION ACT 1965 3 ft. DIVANS complete with Headboard LADIES* WORKING PARTY £ 2 7 i NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT Mr A. A. Baden Fuller, Death Commons Commissioner, will inquire into the references set out in the 3 only: 3-PIECE SUITES. Cream, Brown or Gold i Schedule hereto at the Magistrates’ Court, Wood ho use Close, Bishop MARKET STALL KIRTLEY.—23rd March (in hos Normal price £120. each £100 Auckland, commencing on Tuesday, the 29th day of April, 1975, at i pital), of Hutton Magna, Jack 10-30 o’clock in the forenoon, when all persons interested in the said Wednesday, 26th March (John), aged 60 years, beloved OSMAN BLANKETS. Seconds. 80 x 96. Each references should give their attendance. Hand-made Garments £ 2 - 3 5 i husband of Mary and dearly N.B.—The registration of the land marked with an asterisk in the V loved father of Michael. Service Schedule as common land or as town or village green is not disputed. Cakes and Produce and interment at Hutton Magna OSMAN TERYLENE/COTTON SHEETS. A B. FLETCHER, today, Wednesday, 26th March, Clerk of the Commons Commissioners. A RECITAL OF MUSIC 70 x 108 £3_5Q each 90 x 108 at 2 p.m. I £ 3 - 9 5 each l Watergate House, March, 1975. for m 15 York Buildings, Acknowledgment OBOE AND PIANO ( NYLON PILLOW CASES. Various colours a London, WC2N 6 LB. Ik 6 5 p per pair SCHEDULE ANDREW KNIGHTS, Oboe I i ALDER SON. -

Subject Guide 1 – Records Relating to Inclosure

Durham County Record Office County Hall Durham DH1 5UL Telephone: 03000 267619 Email: [email protected] Website: www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk Subject Guide 1 – Records Relating to Inclosure Issue no. 19 July 2020 Contents Introduction 1 Organisation of List 2 Alphabetical List of Townships 2 A 2 B 2 C 3 D 4 E 4 F 4 G 4 H 5 I 5 K 5 L 5 M 6 N 6 O 6 R 6 S 7 T 7 U 8 W 8 Introduction Inclosure (occasionally spelled “enclosure”) refers to a reorganisation of scattered land holdings by mutual agreement of the owners. Much inclosure of Common Land, Open Fields and Moor Land (or Waste), formerly farmed collectively by the residents on behalf of the Lord of the Manor, had taken place by the 18th century, but the uplands of County Durham remained largely unenclosed. Inclosures, to consolidate land-holdings, divide the land (into Allotments) and fence it off from other usage, could be made under a Private Act of Parliament or by general agreement of the landowners concerned. In the latter case the Agreement would be Enrolled as a Decree at the Court of Chancery in Durham and/or lodged with the Clerk of the Peace, the senior government officer in the County, so may be preserved in Quarter Sessions records. In the case of Parliamentary Enclosure a Local Bill would be put before Parliament which would pass it into law as an Inclosure Act. The Acts appointed Commissioners to survey the area concerned and determine its distribution as a published Inclosure Award. -

County Durham Landscape Character Assessment: Classification

LANDSCAPE CHARACTER THE LANDSCAPE CLASSIFICATION The Landscape Classification The County Durham Landscape Character Assessment identifies landscape types and character areas at three different levels - the regional, the sub-regional and the local. Regional County Character Areas Sub-regional Broad Landscape Types Broad Character Areas See Table 1 Local Local Landscape Types See Table 2 Local Sub-types County Character Areas. County Character Areas are based on Natural England’s Countryside Character Areas. There are 6 Countryside Character Areas in County Durham, all of which extend beyond its administrative boundaries. County Character Areas are effectively those parts of Countryside Character Areas lying within the County. The boundaries of County Character Areas are more precisely drawn than those of Countryside Character Areas as they are based on a more detailed level of assessment. In reality the boundaries between these broad landscape zones are often gradual and progressive and difficult to identify precisely on the ground. The character of County Character Areas may differ in some ways from that of the larger Countryside Character Areas to which they belong. The descriptions of County Character Areas given here in the Landscape Assessment may therefore be slightly different to the descriptions given in other publications for Countryside Character Areas. Broad Landscape Types and Character Areas Broad Landscape Types are landscapes with similar patterns of geology, soils, vegetation, land use, settlement and field patterns identified at a broad sub-regional level. As with County Character Areas, the boundaries between Broad Landscape Types are not always precise, as the change between one landscape and another can be gradual and progressive. -

Walk 9 Bowes East Circular

TeWaelkings I n.d.. ale BOWES EAST CIRCULAR S T A R T A T : BOWES CAR PARK OPPOSITE VILLAGE HALL DISTANCE: 4.3 MILES TIME: 2.75 HOURS Series Walk... A leisurely walk of 3½ miles, along lanes and across fields in the valley of the River Greta. In the churchyard of St. Giles, up the hill on the o. left, is the grave of William Shaw, headmaster of the old school in the N 9 village known as Shaw’s Academy. This became Dotheboys Hall in Dickens’ “Nicholas Nickleby”. Route Information Outdoor Leisure Map 31 From the free car park opposite the Village Hall, by the crossroads at the eastern end of Bowes, you will walk up through the village past St Giles church and Bowes Castle, built in 1170 on the site of an earlier Roman Fort. From there you descend to the River Greta, cross the bridge, and walk east high up in the valley. The return route is part track and part fields lower down nearer the river. From the car park at Bowes (1) walk up general direction, into the woods above through the village. Turn left down a the River Greta. The path leads downhill narrow lane just past the Church (2), and to a track, where you turn left and soon at the bend in the lane is the entrance meet a lane close to Gilmonby Bridge to Bowes Castle. Continue along the (3). Turn right along the lane through lane, past the cemetery on the right, Gilmonby, ignoring a lane on the right, and soon go right through a stone stile to a sign-posted T-junction, marked Rigg on a sign-posted footpath which goes to the left (4). -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

The North Pennines

LANDSCAPE CHARACTER THE NORTH PENNINES The North Pennines The North Pennines The North Pennines Countryside Character Area County Boundary Key characteristics • An upland landscape of high moorland ridges and plateaux divided by broad pastoral dales. • Alternating strata of Carboniferous limestones, sandstones and shales give the topography a stepped, horizontal grain. • Millstone Grits cap the higher fells and form distinctive flat-topped summits. Hard igneous dolerites of the Great Whin Sill form dramatic outcrops and waterfalls. • Broad ridges of heather moorland and acidic grassland and higher summits and plateaux of blanket bog are grazed by hardy upland sheep. • Pastures and hay meadows in the dales are bounded by dry stone walls, which give way to hedgerows in the lower dale. • Tree cover is sparse in the upper and middle dale. Hedgerow and field trees and tree-lined watercourses are common in the lower dale. • Woodland cover is low. Upland ash and oak-birch woods are found in river gorges and dale side gills, and larger conifer plantations in the moorland fringes. • The settled dales contain small villages and scattered farms. Buildings have a strong vernacular character and are built of local stone with roofs of stone flag or slate. • The landscape is scarred in places by mineral workings with many active and abandoned limestone and whinstone quarries and the relics of widespread lead workings. • An open landscape, broad in scale, with panoramic views from higher ground to distant ridges and summits. • The landscape of the moors is remote, natural and elemental with few man made features and a near wilderness quality in places. -

Discover Mid Teesdale

n o s l i W n o m i S / P A P N © Discover Allendale mid Teesdale Including routes to walk, cycle and ride Area covered by detailed route map © Charlie Hedley/Natural England The Teesdale Railway Path and Public Rights of Way are managed by North Pennines Area of Durham County Council Countryside Group, tel: 0191 383 4144. Outstanding Natural Beauty This leaflet has been produced by the North Pennines AONB Partnership and Mid Teesdale Project Partnership. Funded by: The North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) is one of the finest landscapes in the country. It was designated in 1988 and at almost 2,000 sq. kilometres is the second largest of the 40 AONBs and is one of the most peaceful Through: and unspoilt places in England. It is nationally and internationally important for its upland habitats, geology and wildlife, with much of the area being internationally designated. The North Pennines AONB became Britain’s first European Geopark in 2003 in recognition of its internationally important geology and local efforts to use North Pennines AONB Partnership, Weardale Business Centre, The Old Co-op Building, 1 Martin Street, it to support sustainable development. A year later it became a founding member Stanhope, Co. Durham DL13 2UY tel: +44 (0)1388 528801 www.northpennines.org.uk email: [email protected] of the UNESCO Global Geoparks Network. For more information about the AONB, call 01388 528801 or visit This publication is printed on Greencoat Plus Velvet paper: 80% recycled post consumer, FSC The North Pennines AONB Partnership certification; NAPM recycled certification; 10%TCF virgin fibre; 10% ECF fibre. -

The London Gazette, 2 January, 1934 69

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 2 JANUARY, 1934 69 DISEASES OF ANIMALS ACTS, 1894 TO 1927—continued. SHEEP SCAB MOVEMENT AREAS— continued. thence in a south-easterly direction along the road to Bennetston Hall and thence north- easterly along the road to Sparrowpit; thence in an east-south-easterly direction along the road via Peak Forest, Lane Head, Wardlow Mires, Stony Middleton, Calver and Bridge End to Nether End; thence in an easterly direction along the road via Robinhood, Bleak House, Freebirch, Ingmanthorpe and Cutthorpe to Dunston Hall; thence in a general northerly direction along the road via Instone, Dronfield, Little Norton to Norton Woodseats; thence along Woodseats Road till it meets the London Midland and Scottish Railway that runs from Dore and Totley Station to Sheffield; thence in a north- easterly direction along the said railway to a point near to Victoria Station, Sheffield, where the London and North Eastern Railway lines, which run through Sheffield to Penistone, are carried over the said railway; thence in a north-westerly direction along the London and North Eastern Railway as far as Oughtibridge Station; thence in a westerly direction along the road between Grenoside and Oughtibridge to Oughtibridge; thence in a north-westerly direction via Wharncliffe Side, Deepcar, Stocksbridge, Sheephouse Wood, Langsett to Flouch Inn; thence in a westerly direction via Fiddlers Green and Salters- brook Bridge, to the point where the road crosses the London and North Eastern Railway from Penistone to Glossop near the western end of Woodhead Tunnel and thence along the London and North Eastern Railway via Growden to Glossop and the point of commence- ment. -

130319-1 DRAFT Minutes 130219

COTHERSTONE PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of the Parish Council meeting held in Cotherstone Village Hall on Wednesday 13 February 2019 at 7.00pm In attendance: Cllr John Birkett (Chair), Cllr Jenny Watson, Cllr Richard Green, Cllr Robin Quick, Cllr Tim Sabey, Cllr Alan Thorn Absent: Cllr Richard Hunter Public: None Clerk: Judith Mashiter 1. Approval of apologIes for absence As Cllr Hunter had submitted apologies due to being on holiday, it was resolved that his absence be approved. 2. Declarations of Interest None 3. Requests for dIspensatIons No requests had been received. 4. MInutes Draft minutes had been circulated. It was resolved that the minutes of the Parish Council meeting held 9 January 2019 are an accurate record. 5. PublIc partIcIpatIon No public were present. 6. Update on progress of actIons and resolutIons An action log updated 5 February 2019 had been circulated. Following discussion: • It was resolved to amend Cemetery Rules paragraph 13 to require undertaker to inspect grave mound for settlement 12 weeks following interment (rather than 6 weeks) and then close this action. • Quotation now received from AllAboutTrees. Cllr Green declared an interest and took no part in this agenda item. No decision was taken, as further research is required, including seeking help from Dave Martin of Trees for Cotherstone. • Planning application DM/15/02914/FPA (Cart Barn) – Clerk asked to confirm with the Planning Officer that the query was concerning the expansion of the curtilage which was the subject of the planning consent. • Clerk confirmed that Durham County Council’s Rights of Way Officer Mike Murden will be inspecting Footpath 76 this week to assess the damage. -

THE POPLARS, COTHERSTONE Barnard Castle, County Durham

THE POPLARS, COTHERSTONE Barnard Castle, County Durham THE POPLARS, COTHERSTONE BARNARD CASTLE, COUNTY DURHAM, DL12 9QB THE POPLARS IS AN EXTREMELY ATTRACTIVE STONE BUILT DOUBLE FRONTED PROPERTY SET WITHIN DELIGHTFUL GARDENS WITH ANCILLARY SPACE OFFERING OFFICE ACCOMMODATION, GARAGING, WORKSHOP, DETACHED STABLING AND AN ADJOINING 3.28 ACRE PADDOCK WITH A STONE FIELD BARN. THE PROPERTY OFFERS SUBSTANTIAL FOUR BEDROOM ACCOMMODATION IDEAL FOR FAMILY LIVING, BUT ONE OF ITS PRINCIPAL SELLING POINTS IS THE OPPORTUNITY TO PURCHASE A FINE HOUSE OFFERING VERSATILE ACCOMMODATION WITHIN THE CONFINES OF A VILLAGE LOCATION. Accommodation Entrance Vestibule • Hall • Sitting Room• Drawing Room • Dining Room Breakfast Kitchen • Conservatory • Laundry with Separate WC • Office Boot Room • Master Bedroom with En-suite • Three Further Bedrooms Family Bathroom Externally Garaging with Adjoining Workshop • Private Drive • Detached Stabling with Loft Land Extending to Approximately 3.28 acres (1.32 ha) Detached Stone Built Field Barn Barnard Castle 4 miles, Richmond 19 miles, Darlington 25 miles, Bishop Auckland 19 miles, Durham 28 miles, Newcastle 47 miles. Please note all distances are approximate. 12 The Bank, Barnard Castle, Co Durham, DL12 8PQ Tel: 01833 637000 Fax: 01833 695658 www.gscgrays.co.uk [email protected] Offices also at: Bedale Hamsterley Leyburn Richmond Stokesley Tel: 01677 422400 Tel: 01388 487000 Tel: 01969 600120 Tel: 01748 829217 Tel: 01642 710742 Situation & Amenities market and is often referred to as the gateway to Teesdale. Teesdale and the Yorkshire Dales National Park provide picturesque Located within this picturesque and sought after village, which landscape for walking and other outdoor activities. was named as one of the top 10 villages in England and Wales in WEST PASTURE FARM 2008, The Poplars is ideally situated for easy access to the local Numerous golf courses can be found in the area, with courses near Bishop Auckland, Barnard Castle, Durham, Darlington and towns of Barnard Castle, Darlington and Richmond, whilst the Hexham. -

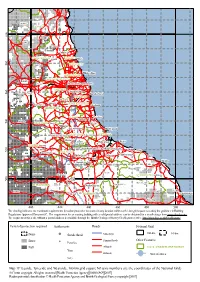

Map 19 Teeside, Tyneside and Wearside, 100-Km Grid Square NZ (Axis Numbers Are the Coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown Copyright

Alwinton ALNWICK 0 0 6 Elsdon Stanton Morpeth CASTLE MORPETH Whalton WANSBECK Blyth 0 8 5 Kirkheaton BLYTH VALLEY Whitley Bay NORTH TYNESIDE NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE Acomb Newton Newcastle upon Tyne 0 GATESHEAD 6 Dye House Gateshead 5 Slaley Sunderland SUNDERLAND Stanley Consett Edmundbyers CHESTER-LE-STREET Seaham DERWENTSIDE DURHAM Peterlee 0 Thornley 4 Westgate 5 WEAR VALLEY Thornley Wingate Willington Spennymoor Trimdon Hartlepool Bishop Auckland SEDGEFIELD Sedgefield HARTLEPOOL Holwick Shildon Billingham Redcar Newton Aycliffe TEESDALE Kinninvie 0 Stockton-on-Tees Middlesbrough 2 Skelton 5 Loftus DARLINGTON Barnard Castle Guisborough Darlington Eston Ellerby Gilmonby Yarm Whitby Hurworth-on-Tees Stokesley Gayles Hornby Westerdale Faceby Langthwaite Richmond SCARBOROUGH Goathland 0 0 5 Catterick Rosedale Abbey Fangdale Beck RICHMONDSHIRE Hornby Northallerton Leyburn Hawes Lockton Scalby Bedale HAMBLETON Scarborough Pickering Thirsk 400 420 440 460 480 500 The shading indicates the maximum requirements for radon protective measures in any location within each 1-km grid square to satisfy the guidance in Building Regulations Approved Document C. The requirement for an existing building with a valid postal address can be obtained for a small charge from www.ukradon.org. The requirement for a site without a postal address is available through the British Geological Survey GeoReports service, http://shop.bgs.ac.uk/GeoReports/. Level of protection required Settlements Roads National Grid None Sunderland Motorways 100-km 10-km Basic Primary Roads Other Features Peterlee Full A Roads LOCAL ADMINISTRATIVE DISTRICT Yarm B Roads Water features Slaley Map 19 Teeside, Tyneside and Wearside, 100-km grid square NZ (axis numbers are the coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown copyright. -

Lartington Hall

THE TEESDALE MERCURY— WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 10, 1917. SECOND DAY’S SALE: Private Wilfred Close, of Bowes, of a York On Thursday, Oot 11th, At Barnard Castle, UPPER DALE NOTES. LOCAL AND OTHER shire Regiment, has had a narrow escape. He At 2-30 p.m. Victoria Hall, COTTAGE and Other RESIDENCES In [BY OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT NOTES. says : “ 1 have just seen Percy Alsopp. He Lartington Village. Sergt. Bradley, who for the past four years has just gone past with rations, up the line. (On Friday, October 12tb). (come November) has been stationed at Captain the Honourable H. C. Vane, Royal I am expecting leave within a fortnight. I and some more were going to the front on the Lartington Hall 24— Oak Tree Villa, with Garden Middleton-in-Teesdale, has been removed to Field Artillery, is officially reported as dangerously ill in hospital at Rouen. He is night of the 27th September, with soup for Near Barnard Castle, Yorkshire 25— Cottage Residence, with Garden Felling-on-Tyne, and is being succeeded by Sergt. Stewart, from Felling. Sergt. Bradley suffering from acute infective jaundice. another company, when Fritz put a bullet (North Riding). 26— Ditto right through the container on my back. It 27— Ditto left on Monday. HIS Charming, Moderate-size COUNTY Cadet Herbert W. Heslop, youngest son of went in at one side and came out at the other. 28— Ditto If 1 bad been six inches further back it would T RESIDENCE will be Sold as Lot 1 of this 29— Detached Villa Residence, with Garden The monthly meeting of the Middleton Major Heslop, of Startforth, has been gazetted far-famed Estate of 6,700 Acres.