The Leicestershire Historian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sources of Langham Local History Information 11Th C > 19Th C

Langham in Rutland Local History Sources of Information Compiled by Nigel Webb Revision 2 - 11 November 2020 Contents Introduction 11th to 13th century 14th century 15th century 16th century 17th century 18th century 19th century Please select one of the above Introduction The intention of this list of possible sources is to provide starting points for researchers. Do not be put off by the length of the list: you will probably need only a fraction of it. For the primary sources – original documents or transcriptions of these – efforts have been made to include everything which might be productive. If you know of or find further such sources which should be on this list, please tell the Langham Village History Group archivist so that they can be added. If you find a source that we have given particularly productive, please tell us what needs it has satisfied; if you are convinced that it is a waste of time, please tell us this too! For the secondary sources – books, journals and internet sites – we have tried to include just enough useful ones, whatever aspect of Langham history that you might wish to investigate. However, we realise that there is then a danger of the list looking discouragingly long. Probably you will want to look at only a fraction of these. For many of the books, just a single chapter or a small section found from the index, or even a sentence, here and there, useful for quotation, is all that you may want. But, again, if you find or know of further especially useful sources, please tell us. -

Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race Author: Thomas William Rolleston Release Date: October 16, 2010 [Ebook 34081] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE*** MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE Queen Maev T. W. ROLLESTON MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE CONSTABLE - LONDON [8] British edition published by Constable and Company Limited, London First published 1911 by George G. Harrap & Co., London [9] PREFACE The Past may be forgotten, but it never dies. The elements which in the most remote times have entered into a nation's composition endure through all its history, and help to mould that history, and to stamp the character and genius of the people. The examination, therefore, of these elements, and the recognition, as far as possible, of the part they have actually contributed to the warp and weft of a nation's life, must be a matter of no small interest and importance to those who realise that the present is the child of the past, and the future of the present; who will not regard themselves, their kinsfolk, and their fellow-citizens as mere transitory phantoms, hurrying from darkness into darkness, but who know that, in them, a vast historic stream of national life is passing from its distant and mysterious origin towards a future which is largely conditioned by all the past wanderings of that human stream, but which is also, in no small degree, what they, by their courage, their patriotism, their knowledge, and their understanding, choose to make it. -

Uppingham - Rutland

Uppingham - Rutland Index of Copyholders Part One The Manor of Preston with Uppingham Uppingham Local History Study Group Peter N Lane (editor) Page -- 1 -- Click here for the Nominum Index The Copyholders Index - Sources and Group Contact Biographical The medieval parish of Uppingham contained two manors known as the Preston Members of the Uppingham Local History Group (the forerunner of the Uppingham with Uppingham Manor and the Rectory Manor. They comprised roughly Local History Study Group) who in the 1970s investigated and recorded the manorial 45% and 15% of the land area respectively and were held in copyhold tenure records of the town and parish of Uppingham. by tenants according to the custom of the manor. The reminder of the parish was held freehold but formed part of the Preston with Uppingham Manor. The David Parkin - Retired solicitor, formerly practicing at Oakham where he served also smaller Rectory Manor was vested in the Rector of Uppingham by the right of his as Clerk to the Governors of the Hospital of St John and St Anne from office for the period of his incumbency. It contained no freehold other than that 1970 to 1991. The Rutland Record Society has published his studies belonging to the parson. Ownership and descent of the larger Preston Manor of Rutland Charities – The History of the Hospital of Saint John the can be consulted in the Victoria County History of Rutland. Evangelist and of Saint Anne of Okeham, Gilson’s Hospital at Morcott The Court Rolls of the Preston Manor comprised 12 volumes, the first written in and Byrch’s Charity at Barrow. -

Wales and the Wars of the Roses Cambridge University Press C

WALES AND THE WARS OF THE ROSES CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS C. F. CLAY, Manager ILcinfcott: FETTER LANE, E.C. EBmburgfj: 100 PRINCES STREET §& : WALES AND THE WARS OF THE ROSES BY HOWELL T. EVANS, M.A. St John's College, Cambridge Cambridge at the University Press 1915 : £ V*. ©amtrrtrge PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS PREFACE AS its title suggests, the present volume is an attempt to ** examine the struggle between Lancaster and York from the standpoint of Wales and the Marches. Contemporary chroniclers give us vague and fragmentary reports of what happened there, though supplementary sources of informa- tion enable us to piece together a fairly consecutive and intelligible story. From the first battle of St Albans to the accession of Edward IV the centre of gravity of the military situation was in the Marches : Ludlow was the chief seat of the duke of York, and the vast Mortimer estates in mid-Wales his favourite recruiting ground. It was here that he experienced his first serious reverse—at Ludford Bridge; it was here, too, that his son Edward, earl of March, won his way to the throne—at Mortimer's Cross. Further, Henry Tudor landed at Milford Haven, and with a predominantly Welsh army defeated Richard III at Bosworth. For these reasons alone unique interest attaches to Wales and the Marches in this thirty years' war; and it is to be hoped that the investigation will throw some light on much that has hitherto remained obscure. 331684 vi PREFACE I have ventured to use contemporary Welsh poets as authorities ; this has made it necessary to include a chapter on their value as historical evidence. -

Domesday in Rutland — the Dramatis Personae

Domesday Book in Rutland The Dramatis Personae Prince Yuri Galitzine DOMESDAY BOOK IN RUTLAND The Dramatis Personae by Prince Yuri Galitzine Rutland Record Society 1986 1986 Published by Rutland Record Society Rutland County Museum, Oakham LE15 6HW © Prince Yuri Galitzine 1986 ISBN 0907464 05 X The extract Roteland by courtesy of Leicestershire Museums and the Domesday Map of Rutland by courtesy of the General Editor, Victoria County History of Rutland The Dramatis Personae of Domesday Book The story of Domesday Book only comes alive when we try to find more about those persons who are mentioned in it by name. The Domesday Book records the names of each of three categories of landowners – the tenants‑in‑chief and the tenants in 1086 – TRW = Tempore Regis Guilielmi and the antecessors, the name given to those who held in 1066 – TRE = Tempore Regis Edwardii. Throughout the whole of England about 200 tenants‑in‑chief arc recorded in Domesday Book holding from the King as overlord of whom 15 held in Rutland. About another 5,000 throughout England held as tenants directly of the King or of his tenants‑in‑chief by knight’s fees. Of the latter, there were 16 in Rutland. Sadly the majority of persons referred to in the record are not identified by name. These are people the landowners controlled and who were established in the villages of Rutland. They comprised 10 priests, 142 freemen, 1147 villagers, 244 small holders and 21 slaves (two of whom were women) ‑ a total of 1564. The tenants-in-chief Not unnaturally as Rutland had been the dowry of the Queens of England since 964, King William had in his direct control the largest share of the lands in Rutland – 24 carucates and 39 hides comprising the town of Oakham and 14 manors valued at £193 12s. -

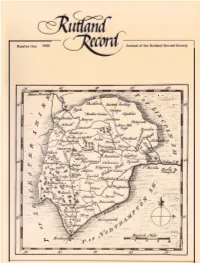

To Rutland Record 21-30

Rutland Record Index of numbers 21-30 Compiled by Robert Ovens Rutland Local History & Record Society The Society is formed from the union in June 1991 of the Rutland Local History Society, founded in the 1930s, and the Rutland Record Society, founded in 1979. In May 1993, the Rutland Field Research Group for Archaeology & History, founded in 1971, also amalgamated with the Society. The Society is a Registered Charity, and its aim is the advancement of the education of the public in all aspects of the history of the ancient County of Rutland and its immediate area. Registered Charity No. 700723 The main contents of Rutland Record 21-30 are listed below. Each issue apart from RR25 also contains annual reports from local societies, museums, record offices and archaeological organisations as well as an Editorial. For details of the Society’s other publications and how to order, please see inside the back cover. Rutland Record 21 (£2.50, members £2.00) ISBN 978 0 907464 31 9 Letters of Mary Barker (1655-79); A Rutland association for Anton Kammel; Uppingham by the Sea – Excursion to Borth 1875-77; Rutland Record 22 (£2.50, members £2.00) ISBN 978 0 907464 32 7 Obituary – Prince Yuri Galitzine; Returns of Rutland Registration Districts to 1851 Religious Census; Churchyard at Exton Rutland Record 23 (£2.50, members £2.00) ISBN 978 0 907464 33 4 Hoard of Roman coins from Tinwell; Medieval Park of Ridlington;* Major-General Lord Ranksborough (1852-1921); Rutland churches in the Notitia Parochialis 1705; John Strecche, Prior of Brooke 1407-25 -

Visitor Guide (See Advert Page 11)

FREE This brochure is the official tourism guide for Rutland and was produced by Leicester Shire Promotions Limited on behalf of Rutland Tourism with support from Rutland County Council. Special thanks to Richard Adams, Roger Rixon, Andy Ward at Creative Link Solutions, The Leicester Mercury, Shakir at iways, RSPB Rutland and the Anglian Water Birdwatching Centre for their photography, and to Philip Dawson for use of the Rutland map. Particular thanks Rutland London go to Chris Hartnoll of CHFI who has provided photography for this guide Visitor Guide (see advert page 11). All information was believed to be correct at the time of going to press. Leicester Shire Promotions cannot accept liability for inaccuracies, omissions or subsequent 07/08 alterations in information supplied. You are advised to check opening times, prices, etc with establishments before your visit. Large print format also available. Please call 0116 225 4000 for details. Produced for by in partnership with Getting to know Rutland Out & About Useful Information Where to Stay © Leicester Shire Promotions Limited 2007 7-9 Every Street, Leicester LE1 6AG www.gorutland.com Getting to Know Rutland 3 History 5 Oakham 9 Uppingham 13 Stamford 15 Rutland Water Out and About 17 Short Break Ideas Rutland. England’s smallest county 23 Gardens and Nature and arguably its finest too. Lying halfway 25 Museums and Stately Homes between London and York, nestling close 27 Historic Buildings and Churches to Leicester, Nottingham, Lincoln and 29 Outdoor Activities Peterborough, Rutland offers visitors 32 Leisure a world of outstanding natural beauty 33 Rutland Map that more than justifies its claim to be 35 Events ‘100 per cent real England’. -

Rutland County Council

Rutland County Council Catmose, Oakham, Rutland, LE15 6HP. Telephone 01572 722577 Facsimile 01572 758307 DX28340 Oakham Meeting: CABINET Date and Time: Tuesday, 15 November 2016 at 9.30 am Venue: COUNCIL CHAMBER, CATMOSE Corporate support Natasha Brown 01572 720991 Officer to contact: email: [email protected] Recording of Council Meetings: Any member of the public may film, audio-record, take photographs and use social media to report the proceedings of any meeting that is open to the public. A protocol on this facility is available at www.rutland.gov.uk/haveyoursay A G E N D A APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 1) ANNOUNCEMENTS FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND/OR HEAD OF THE PAID SERVICE 2) DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST In accordance with the Regulations, Members are required to declare any personal or prejudicial interests they may have and the nature of those interests in respect of items on this Agenda and/or indicate if Section 106 of the Local Government Finance Act 1992 applies to them. 3) RECORD OF DECISIONS To confirm the Record of Decisions made at the meeting of the Cabinet held on 18 October 2016. 4) ITEMS RAISED BY SCRUTINY To receive items raised by members of scrutiny which have been submitted to the Leader (copied to Chief Executive and Democratic Services Officer) by 4.30 pm on Friday 11 November. REPORTS OF THE DIRECTOR FOR RESOURCES 5) QUARTER 2 FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT REPORT (KEY DECISION) Report No. 191/2016 (Circulated under separate cover) 6) MID-YEAR REPORT ON TREASURY MANAGEMENT AND PRUDENTIAL INDICATORS 2016/17 Report No. 197/2016 (Pages 5 - 24) 7) REPORT OF THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE 8) PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT REPORT - QUARTER 2 2016/17 Report No. -

Burley on the Hill Sue Howlett

Burley 1 REV 5/10/07 16:32 Page 1 Chapter 4 Burley on the Hill Sue Howlett Distant view of Burley in the Middle Ages Burley on the Hill with part Even before the coming of Rutland Water, most visitors’ overriding impres- of Burley sion of Burley has always been the great house of Burley on the Hill. For Fishponds in centuries, that first sight has been one to take the breath away. In 1953 it was the foreground glimpsed by two lady travellers as ‘mistily blue in the summer haze, like some (RO) fairy palace set in enchanted woods’ (Stokes 1969, 37). Rutland’s early historian, James Wright, summoned the Muse of Poetry to do justice to the awe-inspiring location: ‘Hail Happy Fabrick, whose auspicious view First sees the sun, and bids him last adieu! Seated in Majesty, your eye commands A Royal Prospect of the richest lands . .’ (Wright 1684, Additions,5) – 55 – Burley 1 REV 5/10/07 16:33 Page 2 The origins of the settlement of Burley are obscure. Its name suggests a fortified place (perhaps an Iron Age hill fort) close to woods, and indeed the Domesday Book of 1086 records extensive woodland one league long by three furlongs (about three miles by three eighths of a mile). This part of Rutland had been settled by Danes, and Burley fell within the Danish-named ‘Wapentake’ (hundred or shire division) of Alstoe. The pre-Conquest meet- ing place may have been the mound, or motte, in what is now the deserted village of Alsthorp. -

Out of Print Click to Download

Number One . .. " .. "'. '\� . .. :,;. :':f..• � .,1- '. , ... .Alt,;'�: ' � .. :: ",' , " • .r1� .: : •.: . .... .' , "" "" "·';'i:\:.'·'�., ' ' • •• ·.1 ..:',.. , ..... ,:.' ::.,::: ; ')"'� ,\:.", . '." � ' ,., d',,,·· '� . ' . � ., ., , , " ,' . ":'�, , " ,I -; .. ',' :... .: . :. , . : . ,',." The Rutland Record Society was formed in May 1979. Its object is to advise the education of the public in the history of the Ancient County of Rutland, in particular by collecting, preserving, printing and publishing historical records relating to that County, making such records accessible for research purposes to anyone following a particular line of historical study, and stimUlating interest generally in the history of that County. PATRON Col. T.C.S. Haywood, O.B.E., J.P. H.M. Lieutenant for the County of Leicestershire with special responsibility for Rutland PRESIDENT G.H. Boyle, Esq., Bisbrooke Hall, Uppingham CHAIRMAN Prince Yuri Galitzine, Quaintree Hall, Braunston, Oakham VICE-CHAIRMAN Miss J. Spencer, The Orchard, Braunston, Oakham HONORARY SECRETARIES B. Matthews, Esq., Colley Hill, Lyddington, Uppingham M.E. Baines, Esq., 14 Main Street, Ridlington, Uppingham HONORAR Y TREASURER The Manager, Midland Bank Limited, 28 High Street, Oakham HONORARY SOLICITOR J.B. Ervin, Esq., McKinnell, Ervin & MitchelI, 1 & 3 New Street, Leicester HONORARY ARCHIVIST G.A. Chinnery, Esq., Pear Tree Cottage, Hungarton, Leicestershire HONORAR Y EDITOR Bryan Waites, Esq., 6 Chater Road, Oakham COUNCIL President, Chairman, Vice-Chairman, Trustees, Secretaries, -

State Library of Massachusetts

REFORT OF THE LIBRARIAN OP THE STATE LIBRARY, FOR THE YEAR ENDING SEPTEMBER 30, 1880; AND FIRST ANNUAL SUPPLEMENT TO THE GENEKAL CATALOGUE. BOSTON: BanÎJ, aberg, Se &o., printers to tije Cammantoealtfj, 117 FRANKLIN STBEET. 1881. oHKii TRUSTEES OF THE STATE LIBRARY. EDWIN P. WHIPPLE .... BOSTON. GEORGE O. SHATTUCK . BOSTON. JACOB M. MANNING .... BOSTON. JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE OF THE LEGISLATURE, 1880. MESSRS. STEPHEN OSGOOD, GEORGETOWN, Of the Senate. JOHN L. OTIS, NORTHAMPTON, MESSRS. ARTHUR J. C. SOWDON, BOSTON, NATHANIEL A. HORTON, SALEM, ARTHUR LINCOLN, HINGHAM, Of the House. A. CARTER WEBBER, CAMBRIDGE. SAMUEL W. BOWERMAN, PITTSFIELB, OFFICERS OF THE LIBEAEY. JOHN W. DICKINSON . LIBRARIAN EX OFFICIO. C. B. TILLINGHAST .... ACTING LIBRARIAN. C. R. JACKSON ASSISTANT. E. M. SAWYER ASSISTANT. Commonrocaltl) of ittassacfjusctts. LIBRARIAN'S REPORT. To the Honorable Legislature of Massachusetts. THE librarian of the State- Library, in accordance with sect. 8 of chap. 5 of the General Statutes, submits the fol- lowing report for the year ending Sept. 30, 1880: — ADDITIONS. Number of Volumes added to the Library from Oct. 1, 1S79, to Sept. 30, 1880. By purchase -••..... 1,285 domestic exchanges 350 foreign exchanges 78 donation 268 officers of government 86 2,067 Pamphlets. By purchase 129 domestic exchanges . ... 39 foreign exchanges ......... 24 donation ........... 463 officers of government ........ 40 695 Maps 17 FINANCIAL STATEMENT. DR. COMMONWEALTH IN ACCOUNT WITII TRUSTEES OF THE STATE LIISRARY. CR. 1879. 1879. Oct. 1, to Expended for periodicals 40 Cash drawn from appropriations for 1878 and 8793 33 Deo. 31, postage . 3 00 1879. newspaper carrier . 75 expressage 10 00 printing . 1 25 covering desk . -

20101009102De.Pdf

jggvr^; isri I |PJ| |PJ| se i ii ii s» s» IlIP 1* 1* BH&BSMHHHBB9HH^BBB9Hn9H^Bii9i IIs HHtS i ii*£^ t^i^?' Rlillj f !5; i;. '¦; 9. ¦ ¦ 11•• t* ¦ ¦ fix (31 II ,i Pi? I iiiI I I 1Sf? I*- t« KVp&V' tj E^ >' E« j! = — — M E 1 =c ~mm mZ > H r ~* I = (fl 0 o> 1 0 O > =00 -< M M o P 0 ¦n = o 2 O t* ¦ to 0 ro JJ z o <a o 2 X 0 o m E* pi u> (/> =IA E^1 = W Icn-i = M ~ w — i -\ THE DESCENT OF THE FAMILY OF D EACO N OF ELSTOWE AND LONDON, WITH SOME GENEALOGICAL, BIOGRAPHICAL AND TOPOGRAPHICAL NOTES, AND SKETCHES OF ALLIED FAMILIES INCLUDING REYNES } ( MERES AND OF > J OF CLIFTON, ) v KIRTON. BY i EDWARD DEACON, Hon. Treas. Fairfield Co. Historical Society, Conn. Bridgeport, Conn. 1898. 2075 i Grove Cottage, Residence ofEdward Deacon, Bridgeport, Conn, TO -THE MEMORY OF MY FATHER AND MOTHER. " /// this world, Who can do a tiling, willnot ; And who would do it, cannot, Iperceive : " Yet the will's somewhat Browning. PREFACE. This work being intended for private distribution only, to members of the family, and possibly to a few societies inter ested in genealogy, no apology is needed for the personal character of some of its contents. Ithas been a labor of love during: the past eighteen years to gather the facts herein presented, and the writer has the satisfaction of knowing that he has succeeded in bringing to light from the musty documents of distant centuries, some interesting material which has never before seen print.