Transactions Discovery Lodge of Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trestleboard M ARCH 2004

NEW JERSEY LODGE OF MASONIC RESEARCH AND EDUCATION NO. 1786 V OLUME 2 I SSUE 2 Trestleboard M ARCH 2004 The purpose of the NJ Lodge of Masonic Research and Educaon is to foster the educaon of the Cra at large through prepared research and open discussion of the topics concerning Masonic history, symbolism, philosophy, and current events. Next Communication The New Jersey Lodge of Masonic Research and Education meets on the fourth Saturday in January, March, May. INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Our next communication will be held on Saturday, March 20, 2004 at 10:00 a.m. at : From the East 2 From the West 3 Trenton Masonic Temple 100 Barracks Street Secretary’s Corner 3 Trenton, New Jersey LORE Application 4 ALL MASTER MASONS ARE WELCOME! Masonic Book List 5-6 Book Review 8 P AGE 2 V OLUME 2 I SSUE 2 From the East RW George A. Olsen, Worshipful Master RWB George Olsen is at home recovering from surgery. Please keep him in your thoughts and prayers during his period of recuperation. From The West Bro. Tom Thorton, Senior Warden My Brothers, We are now completing our first two years of operation. It is good news and it is bad news. The good news, we have had excellent papers presented at each of our meetings. The sad news is most have been from just two writers. It was hoped that with over 20,000 Masons in the state there would be a few more interested in writing about Freemasonry. And please remember research does not mean digging up and detailing the past. -

To Learn About the History of Castle Island Virtual Lodge No

Castle Island Virtual Lodge No. 190 “A research Lodge for Digital Freemasonry “ This presentation will provide the background and details on Canada’s first Virtual Education Lodge Worshipful Brother Nicholas Laine Secretary (IPM) Castle Island Virtual Lodge No. 190 – GRM Head Steward Endeavour Lodge No. 944 – UGLV Tyler Burlington Lodge No. 190 - GRC Castle Island Virtual Lodge Mission statement: “To aid in the Education of Brethren around the world. To shape the fraternity’s future relevance in the lives of men through a quality program” Agenda: Canadian Geography & Grand Lodge of Manitoba CIV Lodge and its current officers around the world Discussion the Lodge and its evolution since 2012 Speakers/Presentations within our Education platform Current Members of the Lodge Meeting Schedule for 2019 Affiliation process Feedback from the Brethren Lodge Education Examples Evolution of Virtual Lodges across the world Endeavour Lodge 944 - UGLV Canada & The Grand Lodge of Manitoba In Manitoba, the Grand Lodge of Manitoba, Ancient Free and Accepted Masons was formed in 1875. It is the governing body of the forty three Masonic Lodges located throughout the province. Why create a Virtual Lodge in Manitoba In 2012 Four Past Grand Masters and the sitting Grand Master Most Worshipful Dave Love, saw a need to create a Education platform to service the wide expanse of the Prairie province of Manitoba. They had a 500 vision to create an Miles Education Lodge could service the Servicemen, shut-ins and population of Manitoba. Our Lodge Officers JW The Officers of Castle Island G L Virtual Lodge of span four MB IPM Countries and five time zones. -

Lodges of Research

LODGES OF RESEARCH Presented by Dan M. Kemble, Master, William O. Ware Lodge of Research, at Lexington Lodge No. 1, Lexington, Kentucky, February 19, 2019. It’s an honor and pleasure to be speaking to you tonight. I would like to thank the Worshipful Master for his invitation and thank you for being here this evening. Allow me to begin with a disclaimer: the statements, thoughts and opinions expressed in this presentation are mine. They do not necessarily represent the positions any Lodge or Grand Lodge. When Masons talk about the last fifty years, we generally talk about the dramatic decline in Lodge membership over that period of time. Equally dramatic, however, in that same period of time is the increase in the availability of information regarding Freemasonry. Information about the Fraternity is delivered to our desktops and cell phones through technological advances that seemingly have no end in sight. The “Age of Information” in which we live has not ignored Freemasonry, although we are at times slow to take advantage of its resources. Those interested in learning more about Freemasonry can visit various Lodge and Grand Lodge websites, listen to podcasts, read blogs and even attend a “virtual” Lodge. In addition to information available electronically, there are organizations such as “The Masonic Society” and “The Philalethes Society” that publish quarterly journals containing scholarly works on subjects of interest to Freemasons. In something of a chicken or egg manner, the thirst for Masonic knowledge and the increase of electronic resources and other print media providing information about Freemasonry seem, at least for the time being, to fuel each other. -

Knights Templar Eye Foundation

VOLUME LXIII JANUARY 2017 NUMBER 1 KT_EliteCC_Bomber_0117_Layout 1 11/15/16 12:53 PM Page 1 Presenting a Unique Knight Templar Fine Leather Jacket As A siR KnighT YOU hAvE EARnEd ThE RighT TO WEAR This JACKET! • Features include your choice of black or brown fine leather, tailored with outside storm flap, pleated bi-swing back, knit cuffs and waistband, two side-entry double welt pockets, two large front- Featuring A York Rite Bodies Woven Emblem flapped cargo pockets, nylon inner lining with fiberfill and and Optional “Concealed Carry” Feature heavy-duty jacket zipper. • A further option is two inner pockets to secure valuables, which are also fitted with LAST CALL “concealed carry” holster FOR WINTER straps for those licensed 2017! to carry a firearm. • Bomber Jacket comes in sizes ranging from small to 3XL (sizes 2XL–3XL are $25* extra.) • Your satisfaction is guaranteed 100% by Masonic Partners and you may return your jacket within 30 days of purchase for replacement or refund - no questions asked. • Thank you priced at just $199*, with an interest-free payment plan available. (See order form for details). Military Veterans can add their Service Branch or ORdER TOdAY Vietnam Veteran patch to their Jacket. (See choices below.) And RECEivE A * FREE “PROUd TO BE A MAsOn” ziPPER PULL! *United States Marine Corps patch provided by Sgt. Grit Marine Specialties. CALL TOLL FREE TO ORDER: IF YOU WEAR THIS SIZE: 34-36 38-40 42-44 46-48 50-52 54-56 † † sizing ORDER THIS SIZE: SML XL XXL 3XL 1-800-437-0804 MON - FRI 9AM - 5PM EST. -

Masonry and the Constitution

THE IMPACT OF MASONRY ON THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION May - September 1787 by Stewart Wilson Miner, PGM The purpose of this paper is to suggest how and those restrictive purposes, they wrote relatively to what degree Freemasonry exerted an little. influence over the delegates and their work at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Nevertheless, many of Masonry's students, Pennsylvania, in the epochal year of 1787. A despite the fragmentary nature of the evidence number of Masons attended the Convention, as at hand, attribute great political importance to we know, and we are told that among the 39 the Craft during the Eighteenth Century. Among signers of the Fundamental Law that they those who have done so is Bernard Fay, a produced, 13 were at some time in their lives distinguished scholar who in 1935 wrote a associated with Masonry. Of that number, 11 lengthy opus entitled Revolution and were Freemasons at the time that they Freemasonry 1680-1800. In that work he participated in the Convention. Subsequent to remarked that from the Middle Ages, the Convention, two others, William Patterson Freemasonry in England was a social force. of New Jersey and James McHenry of "Through their technical secrets gathered from Maryland, became Masons in 1791 and 1806, all corners of the globe, the glory acquired by respectively. their achievements and the numerous great people who wished to be affiliated with that My interest, however, is not in numbers but in great guild," he said, "the Masons held ideas. What did the delegates think, and why did tremendous power." It was his observation that they think as they did? Were the thoughts of with the advent of the Renaissance, a period of Masons in the Convention distinguishable from decadence began, and in consequence the the thoughts of their non-Masonic counterparts Masons lost some of their power, though they and, if so, were their opinions shaped by their retained their popularity. -

Anti-Masonry, and Our Response

Anti-Masonry, And Our Response Wallace McLeod Virginia Research Lodge No. 1777 June 27th, 1998 INTRODUCTION Worshipful Master, Distinguished Masons, and my Brethren: let me begin by saying how very grateful I am to your Secretary, Wor. Brother Keith A. Hinerman, for inviting me to be with you today, and for arranging all the details of my visit with such thoughtful care. And he has been so good to us on our previous visits! Actually, as your Lodge circular notes, this is the third time that I have been privileged to address Virginia Research Lodge. The first was fourteen years ago (on June 23, 1984), when I talked about "The Sufferings of John Coustos." Then, just five years ago (on June 26, 1993), I spoke on "The Evolution of the Masonic Ritual." Those times now seem like a different age. In both of my earlier visits, I came at the invitation of my dear friend, mentor, and editor, the late Allen Earl Roberts, who died on March 13, 1997, in his 80th year. In the words of John J. Robinson, Allen was "the most prolific author, perhaps in all of Masonic history." He was certainly the most effective educator. He saw what American Masons needed, and then went ahead and gave it to them. He did so much for Masonry, wrote so many indispensable Masonic books, produced so many superb Masonic moving pictures. And many of his publications are still available, at very reasonable prices, from the firm that he founded, Anchor Communications. And of course he was Master of Virginia Research Lodge, No 1777, in 1965-67, and served as its Secretary from 1973 to 196. -

The American Doctrine: a Concept Under Siege Stewart W

The American Doctrine: A Concept Under Siege Stewart W. Miner Virginia Research Lodge No. 1777 March 21, 1992 Setting the Stage I have been interested for many years in the way and manner that Grand Lodges exercise jurisdictional power. By custom, practice, and law Grand Masters and Grand Lodges have in the past assumed, allocated, and implemented almost unlimited authority to the end that Masonic organization and operation has taken on near-monopolistic, if not near- oligarchic, characteristics. Seemingly, moreover, the resultant unique system has been subject, for the most part, to only minimal and periodic challenge. In consequence Grand Lodges have become powers within themselves, answerable on occasion to the membership, but free, by and large, to rigidly control and protect their interests within the confines of proclaimed jurisdictional limits. In furthering this conception of power it has been a common practice for Grand Lodges to declare sovereign authority over all Masons and all lodges within their purview, and in some instances even to claim exclusive Masonic jurisdiction over every male — Mason or not — within their domain. These efforts, in short, while protecting parochial interests, have been undeniably restrictive. In the past quarter-century, however, serious challenges to the authority of Grand Lodges have been launched by individual Masons, by some highly placed leaders in the appendant and coordinate bodies, and by many who themselves lead or have led Grand Lodges. These challenges have caused the initiation of efforts to review Masonic laws and customs, particularly as they pertain to the concept of exclusive territorial jurisdiction — the so-called American Doctrine — in several jurisdictions. -

Faith Hope and Charity

"FAITH, HOPE, AND CHARITY" In the Entered Apprentice lecture we learn that the covering of a lodge is a clouded canopy, or starry-decked heavens, where every good Mason hopes at last to arrive. We learn about that spiritual ladder Jacob saw in his vision, from Genesis Chapter 28: "And he dreamed, and behold a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven: and behold the angels of God ascending and descending on it." Masonic tradition informs us the three principal rungs are labelled Faith, Hope and Charity. But interestingly, those words do not appear in Genesis, but rather 1 Corinthians Chapter 13: "And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity." The men who crafted our ritual saw fit to unite these ideas, and they work together well, if separated a bit biblically. Let us expand on these virtues, how they relate to Freemasonry, and how to pursue them in our daily lives. FAITH Faith and religion are often confused; religion has been defined as: 1 "The belief in and worship of a superhuman controlling power, especially a personal God or gods." While faith is defined in Hebrews 11: "Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen." You might say, faith is trusting in something you cannot explicitly prove. You must have faith in God to be a Mason. But how you exercise that faith, the doctrine you follow, the means of expressing it, may rightly be called your religion, and that decision is left to the individual Mason. -

Paper's of Full Members Texas Lodge of Research

Paper's of Full Members Texas Lodge of Research Clifford L Acker A Masonic Myth Explored. Acker, C. L. XXIX (1993-1995) 165-180. Frank W Amadon III History of Eagle Masonic Lodge No. 41, A.F. & A.M. XL (2005) 69-95 Herbert C Arbuckle III Nacio-Vivio-y-Mario. XXIX (1993-1995) 95-98. Que Hombre! XXXIX (2004-2005) 96-99 Jimmy Rogers: In History and Song XLI (2006-2007) 52-64 Jack E Beeler Moses Johnson, M.D. 1808-1853. XVIII (1982) 41-47. The Masonic Trio of Calhoun County, Texas: Or: Why all the Confusion? XIX (1983) 52-63. Why All the Confusion? a History of Lavaca Lodge No. 36. XIX (1983) 52-63. Early Masons of the Texas Coastal Bend. XXI (1985) 104-113. James R Beeler Destiny and Mr. Clark. XXI (1985) 47-60. Alan Bell An Egyptian Journey: Thoughts on the Origins of Freemasonry Joseph E Bennett John B. Jones and the Frontier Battalion. Bennett, J. E. XXVII (1991) 107-111. Porter T Bennett The Development of a Lodge Educational Program. I (1959) 202-208. Upton Bernard History of the Velasco Masonic Library Association. XXVI (1990) 64-75. Bradley S Billings The Beginnings of Texas Lodge of Research. XLIII (2008) 77-84 The Lubbock Committee: The Premier Study Group of Texas Lodge of Research The Heraldry of Texas Lodge of Research A N Blanton History of Kaufman Lodge No. 726, A. F. & A. M., Scurry. III (1965-1968) 257-278. Ron Blue Gemmell: Building the House of Masonry. XXVIII (1992) 88-93. Willy F Bohlmann Jr Lyons Lodge No. -

Black Freemasonry

Black Freemasonry Douglas T. Boynton Virginia Research Lodge No. 1777 March 9, 2002 Introduction I became interested in the subject when a black man with whom I worked told me he had petitioned a Prince Hall lodge. We were talking one day after his initiation, when he mentioned that seventeen people were initiated during the one Saturday meeting. I asked him where in line he was to receive his degree. He told me that he had started out near the middle of the line, but that by the time they reached the altar, he had worked his way up to the front of the line. At that point in time, I knew that I wanted to find out more about this group of Freemasons with whom we hold no conversation. As he progressed through the degrees, I began to learn more about how the Prince Hall lodges handled the degree candidates. It seems that all the Prince Hall lodges in the district hold a joint communication on a Saturday once a quarter to conduct the degree work for all candidates for the degree in which they are working that day. All candidates were given a coded sheet to assist in learning the memory work. The Saturday before the called communication, all candidates meet with their mentor who determines which candidates can answer which specific questions and then arranges them for examination so that each candidate has a question or questions he can answer. Harold Van Buren Voorhis in his book "Negro Masonry in the United States", published in 1940 contends that we wrongly brand Prince Hall Lodges as "clandestine" since their original authority was from a proper Grand Based on the history of African Lodge, which we will discuss later. -

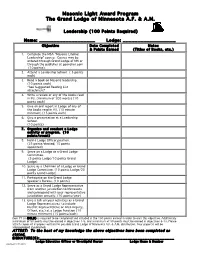

Masonic Light Award Program Proficiencies

Masonic Light Award Program The Grand Lodge of Minnesota A.F. & A.M. Leadership (100 Points Required) Name: ___________________ Lodge: __________________ Objective Date Completed Notes & Points Earned (Titles of Books, etc.) 1. Complete the MSA “Masonic Lifeline: Leadership” course. Course may be ordered through Grand Lodge of MN or through the publisher at goanchor.com (10 points). 2. Attend a Leadership School. ( 5 points each) 3. Read a book on Masonic leadership. (10 points each) *See Suggested Reading List attachment* 4. Write a review of any of the books read in #3. (minimum of 300 words) (10 points each) 5. Give an oral report in Lodge of any of the books read in #3. (10 minute minimum) (15 points each) 6. Give a presentation at a Leadership School. (10 points) 7. Organize and conduct a Lodge activity or program. (10 points/event) 8. Hold a Lodge Officer position. (25 points/elected, 15 points appointed) 9. Serve on a Lodge or a Grand Lodge Committee. (5 points Lodge/10 points Grand Lodge) 10. Serve as a Chairman of a Lodge or Grand Lodge Committee. (10 points Lodge/20 points Grand Lodge) 11. Participate on the Grand Lodge Speaker’s Bureau. (10 points) 12. Serve as a Grand Lodge Representative from another jurisdiction to Minnesota and correspond with your representative jurisdiction annually. (10 points/year) 13. Give a talk on your activities as a Grand Lodge Representative,( to include District Representative or Area Deputy, Officer, etc.) at a Lodge Function (10 minute minimum) (15 points/each) Item #7 (in BOLD) is required to be completed and included in the 100 points earned in order to earn this objective. -

Masonic Education: a Subject Too Often Overlooked Richard E

Masonic Education: A Subject Too Often Overlooked Richard E. Fletcher Virginia Research Lodge No. 1777 June 22, 1991 Conrad Hahn, a most distinguished Mason, once observed, "The lack of educational work in the average lodge is the principal reason for the lack of interest and the consequent poor attendance in Masonry over which spokesman have been wringing their hands for at least a century". This quote stirs one to think about the importance and value of Masonic education within the Masonic Fraternity. It should further stir us to think about why this important aspect of Freemasonry has been so badly overlooked. We must not kid ourselves into thinking that Masonic education is playing the prominent part in Freemasonry that by right it should. This leads to the all-important question, "Why has this situation come about?" The real problem in trying to answer this question is that there is no easy answer. We, as a Fraternity, have reached the point where far too few of our members have even the faintest idea of why they are Freemasons, let alone, have any real knowledge about our history and heritage. To those of you who are "ritual purists" please do not let my next statement shock you. But the real truth of the matter is — we have come to depend on the ritual as the basis for Masonic knowledge. The ritual does not make Masons. It only makes members! We cheat, wrong and defraud any candidate who is left hanging at the end of the 3rd Degree, having heard a lot of words and really not knowing what they mean.