Putti As Moralizers in Four Prints by Master HL Megan L. Erickson A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egbert Haverkamp Begemann Rembrandt the Holy Family, St

REMBRANDT THE HOLY FAMILV, ST PETERSBURG PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED H.W. Janson, Form follows function- o-r does it? Modernist design themy and the histmy of art (The First Gerson Lecture, held on October 2, 1981) D. Freedberg, Iconoclasts and thei-r motives (The Second Gerson Lecture, held on October 7, 1983) C. H. Smyth, Repat-riation of art from the collecting jJoint in Munich afte-r WoTld Wa-r ff (The Third Gerson Lecture, held on March 13, 1986) A. Martindale, Hemes, ancesto-rs, Telatives and the biTth of the jJoTtmit (The Fourth Gerson Lecture, held on May 26, 1988) L. N ochlin, Bathtime: Reno iT, Cezanne, DaumieT and the p-ractices of bathing in nineteenth-century Fmnce (The Sixth Gerson Lecture, held on November 2 1, 1991) M. Warnke, Laudando Pmecipere, der Medicizyklus des Peter Paul Rubens (Der siebente Gerson Vortrag, am rS. November 1993 gehalten) EDITOR'S NOTE The 5th Gerson Lecture was held in 1989. Its final text was made available to the Gerson Lectures Foundation in 1991 . At that moment, an unhappy coincidence of circumstances made publication without further delay impossible. We regret the fact that we had to disappoint the supporters of ow- Foundation for such a long period. Now at last, we are able to publish this lecture, thanks to the generous sponsoring 'in kind' ofWaanders Uitgevers. The Fifth Gerson Lecture held in memoryofHorstGerson (1907-1978) in the aula of the University ofGroningen on the 16th ofNovember 1989 Egbert Haverkamp Begemann Rembrandt The Holy Family, St Petersburg Groningen T he Gerson Lectures Foundation 1995 l REMBRANOT The Holy Family, 1645 4 REMBRANDT THE HOLY FAMILY, ST PETERSBURG Horst Gerson was a remarkable art historian and a remarkable man. -

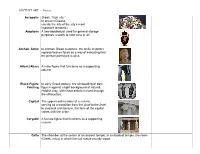

Acanthus a Stylized Leaf Pattern Used to Decorate Corinthian Or

Historical and Architectural Elements Represented in the Weld County Court House The Weld County Court House blends a wide variety of historical and architectural elements. Words such as metope, dentil or frieze might only be familiar to those in the architectural field; however, this glossary will assist the rest of us to more fully comprehend the design components used throughout the building and where examples can be found. Without Mr. Bowman’s records, we can only guess at the interpretations of the more interesting symbols used at the entrances of the courtrooms and surrounding each of the clocks in Divisions 3 and 1. A stylized leaf pattern used to decorate Acanthus Corinthian or Composite capitals. They also are used in friezes and modillions and can be found in classical Greek and Roman architecture. Amphora A form of Greek pottery that appears on pediments above doorways. Examples of the use of amphora in the Court House are in Division 1 on the fourth floor. Atrium Inner court of a Roman-style building. A top-lit covered opening rising through all stories of a building. Arcade A series of arches on pillars. In the Middle Ages, the arches were ornamentally applied to walls. Arcades would have housed statues in Roman or Greek buildings. A row of small posts that support the upper Balustrade railing, joined by a handrail, serving as an enclosure for balconies, terraces, etc. Examples in the Court House include the area over the staircase leading to the second floor and surrounding the atria on the third and fourth floors. -

An Iconographical Analysis Based on the Erwin Panofsky Theory on the Malayness in the Paintings of Amron Omar and Haron Mokhtar

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 10, No. 9, 2020, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2020 HRMARS An Iconographical Analysis Based on the Erwin Panofsky Theory on the Malayness in The Paintings of Amron Omar and Haron Mokhtar Ahmad Hakim Abdullah, Yuhanis Ibrahim and Raja Iskandar Raja Halid To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i9/7835 DOI:10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i9/7835 Received: 11 June 2020, Revised: 16 July 2020, Accepted: 18 August 2020 Published Online: 23 September 2020 In-Text Citation: (Abdullah, Ibrahim, and Halid, 2020) To Cite this Article: Abdullah, A. H., Ibrahim, Y., and Halid, R. I. R. (2020). An Iconographical Analysis Based on the Erwin Panofsky Theory on the Malayness in The Paintings of Amron Omar and Haron Mokhtar. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences. 10(9), 589-601. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 10, No. 9, 2020, Pg. 589 - 601 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 589 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. -

Plant Motifs on Jewish Ossuaries and Sarcophagi in Palestine in the Late Second Temple Period: Their Identification, Sociology and Significance

PLANT MOTIFS ON JEWISH OSSUARIES AND SARCOPHAGI IN PALESTINE IN THE LATE SECOND TEMPLE PERIOD: THEIR IDENTIFICATION, SOCIOLOGY AND SIGNIFICANCE A paper submitted to the University of Manchester as part of the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Humanities 2005 by Cynthia M. Crewe ([email protected]) Biblical Studies Melilah 2009/1, p.1 Cynthia M. Crewe CONTENTS Abbreviations ..............................................................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1 Plant Species 1. Phoenix dactylifera (Date palm) ....................................................................................................6 2. Olea europea (Olive) .....................................................................................................................11 3. Lilium candidum (Madonna lily) ................................................................................................17 4. Acanthus sp. ..................................................................................................................................20 5. Pinus halepensis (Aleppo/Jerusalem pine) .................................................................................24 6. Hedera helix (Ivy) .........................................................................................................................26 7. Vitis vinifera -

Erwin Panofsky, Leo Steinberg, David Carrier

Erwin Panofsky, Leo Steinberg, David Carrier: The Problem of Objectivity in Art Historical Interpretation Author(s): David Carrier Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 47, No. 4 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 333- 347 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The American Society for Aesthetics Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/431133 . Accessed: 24/04/2012 07:48 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Blackwell Publishing and The American Society for Aesthetics are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. http://www.jstor.org DAVID CARRIER ErwinPanofsky, Leo Steinberg,David Carrier:The Problemof Objectivityin Art HistoricalInterpretation My cheeky title was inspiredby an anonymous tive "as objectively as possible" and yet "when reader's complaint in a rejection letter: "and they ... compared ... their efforts ... their tran- what's worse, at one point Carrier even com- scripts differed to a surprisingextent." Under- pares himself to Panofsky." But why indeed standing"these limits to objectivity"may, Gom- shouldI not comparemyself to him, since doing brich suggests, help us understandnaturalistic that is not, absurdly,to imply that my work is images. -

The Early Netherlandish Underdrawing Craze and the End of a Connoisseurship Era

Genius disrobed: The Early Netherlandish underdrawing craze and the end of a connoisseurship era Noa Turel In the 1970s, connoisseurship experienced a surprising revival in the study of Early Netherlandish painting. Overshadowed for decades by iconographic studies, traditional inquiries into attribution and quality received a boost from an unexpected source: the Ph.D. research of the Dutch physicist J. R. J. van Asperen de Boer.1 His contribution, summarized in the 1969 article 'Reflectography of Paintings Using an Infrared Vidicon Television System', was the development of a new method for capturing infrared images, which more effectively penetrated paint layers to expose the underdrawing.2 The system he designed, followed by a succession of improved analogue and later digital ones, led to what is nowadays almost unfettered access to the underdrawings of many paintings. Part of a constellation of established and emerging practices of the so-called 'technical investigation' of art, infrared reflectography (IRR) stood out in its rapid dissemination and impact; art historians, especially those charged with the custodianship of important collections of Early Netherlandish easel paintings, were quick to adopt it.3 The access to the underdrawings that IRR afforded was particularly welcome because it seems to somewhat offset the remarkable paucity of extant Netherlandish drawings from the first half of the fifteenth century. The IRR technique propelled rapidly and enhanced a flurry of connoisseurship-oriented scholarship on these Early Netherlandish panels, which, as the earliest extant realistic oil pictures of the Renaissance, are at the basis of Western canon of modern painting. This resulted in an impressive body of new literature in which the evidence of IRR played a significant role.4 In this article I explore the surprising 1 Johan R. -

Antique Arms, Modern Sporting Guns & Exceptional Firearms

Antique Arms, Modern Sporting Guns & Exceptional Firearms Montpelier Street, London I 3 December 2020 Antique Arms, Modern Sporting Guns & Exceptional Firearms Montpelier Street, London | Thursday 3 December 2020 Antique Arms: Lots 1 - 116 at 10.30am Modern Sporting Guns & Exceptional Firearms: Lots 117 - 363 at 2pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES SALE NUMBER IMPORTANT INFORMATION Montpelier Street Antique Arms & Armour 25987 Please note that lots of Iranian Knightsbridge, Director London SW7 1HH Please see page 2 for bidder and Persian origin are subject David Williams to US trade restrictions which www.bonhams.com +44 (0) 20 7393 3807 information including after-sale collection and shipment currently prohibit their import +44 (0) 7768 823 711 mobile into the United States, with no VIEWING [email protected] exemptions. BY APPOINTMENT ONLY Please see back of catalogue for important notice to bidders Sunday 29 November Modern Sporting Guns Similar restrictions may apply 11am – 3pm William Threlfall to other lots. Monday 30 November Senior Specialist ILLUSTRATIONS 9am – 7pm +44 (0) 20 7393 3815 Front cover: Lots 345 & 337 It is the buyers responsibility Tuesday 1 December [email protected] Back cover: Lot 38 to satisfy themselves that the 9am – 4.30pm Inside front cover: Lot 98 lot being purchased may be Wednesday 2 December Administrator Inside back cover: Lot 56 imported into the country of 9am – 4.30pm Helen Abraham destination. +44 (0) 20 7393 3947 REGISTRATION BIDS [email protected] IMPORTANT NOTICE The United States Government +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Please note that all customers, has banned the import of ivory To bid via the internet Junior Cataloguer irrespective of any previous activity into the USA. -

Dutch and Flemish Art in Russia

Dutch & Flemish art in Russia Dutch and Flemish art in Russia CODART & Foundation for Cultural Inventory (Stichting Cultuur Inventarisatie) Amsterdam Editors: LIA GORTER, Foundation for Cultural Inventory GARY SCHWARTZ, CODART BERNARD VERMET, Foundation for Cultural Inventory Editorial organization: MARIJCKE VAN DONGEN-MATHLENER, Foundation for Cultural Inventory WIETSKE DONKERSLOOT, CODART English-language editing: JENNIFER KILIAN KATHY KIST This publication proceeds from the CODART TWEE congress in Amsterdam, 14-16 March 1999, organized by CODART, the international council for curators of Dutch and Flemish art, in cooperation with the Foundation for Cultural Inventory (Stichting Cultuur Inventarisatie). The contents of this volume are available for quotation for appropriate purposes, with acknowledgment of author and source. © 2005 CODART & Foundation for Cultural Inventory Contents 7 Introduction EGBERT HAVERKAMP-BEGEMANN 10 Late 19th-century private collections in Moscow and their fate between 1918 and 1924 MARINA SENENKO 42 Prince Paul Viazemsky and his Gothic Hall XENIA EGOROVA 56 Dutch and Flemish old master drawings in the Hermitage: a brief history of the collection ALEXEI LARIONOV 82 The perception of Rembrandt and his work in Russia IRINA SOKOLOVA 112 Dutch and Flemish paintings in Russian provincial museums: history and highlights VADIM SADKOV 120 Russian collections of Dutch and Flemish art in art history in the west RUDI EKKART 128 Epilogue 129 Bibliography of Russian collection catalogues of Dutch and Flemish art MARIJCKE VAN DONGEN-MATHLENER & BERNARD VERMET Introduction EGBERT HAVERKAMP-BEGEMANN CODART brings together museum curators from different institutions with different experiences and different interests. The organisation aims to foster discussions and an exchange of information and ideas, so that professional colleagues have an opportunity to learn from each other, an opportunity they often lack. -

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Faya Causey With technical analysis by Jeff Maish, Herant Khanjian, and Michael R. Schilling THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM, LOS ANGELES This catalogue was first published in 2012 at http: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data //museumcatalogues.getty.edu/amber. The present online version Names: Causey, Faya, author. | Maish, Jeffrey, contributor. | was migrated in 2019 to https://www.getty.edu/publications Khanjian, Herant, contributor. | Schilling, Michael (Michael Roy), /ambers; it features zoomable high-resolution photography; free contributor. | J. Paul Getty Museum, issuing body. PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads; and JPG downloads of the Title: Ancient carved ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum / Faya catalogue images. Causey ; with technical analysis by Jeff Maish, Herant Khanjian, and Michael Schilling. © 2012, 2019 J. Paul Getty Trust Description: Los Angeles : The J. Paul Getty Museum, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references. | Summary: “This catalogue provides a general introduction to amber in the ancient world followed by detailed catalogue entries for fifty-six Etruscan, Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Greek, and Italic carved ambers from the J. Paul Getty Museum. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a The volume concludes with technical notes about scientific copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4 investigations of these objects and Baltic amber”—Provided by .0/. Figures 3, 9–17, 22–24, 28, 32, 33, 36, 38, 40, 51, and 54 are publisher. reproduced with the permission of the rights holders Identifiers: LCCN 2019016671 (print) | LCCN 2019981057 (ebook) | acknowledged in captions and are expressly excluded from the CC ISBN 9781606066348 (paperback) | ISBN 9781606066355 (epub) BY license covering the rest of this publication. -

Bareiss Collection Attic Black-Figured Amphorae, Neck-Amphorae, Kraters, Stamnos, Hydriai, and Fragments of Undetermined Closed Shapes

CORPVS VASORVM ANTIQVORVM UNITED STATES OF AMERICA • FASCICULE 23 The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, Fascicule 1 This page intentionally left blank UNION ACADÉMIQUE INTERNATIONALE CORPVS VASORVM ANTIQVORVM THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM • MALIBU Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection Attic black-figured amphorae, neck-amphorae, kraters, stamnos, hydriai, and fragments of undetermined closed shapes ANDREW J. CLARK THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM FASCICULE 1 • [U.S.A. FASCICULE 23] 1988 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Corpus vasorum antiquorum. [United States of America.] The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu. (Corpus vasorum antiquorum. United States of America; fase. 23- ) Vol. i by Andrew J. Clark. At head of title : Union académique internationale. Includes index. Contents: v. i. Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection: Attic black-figured amphorae, neck-amphorae, kraters, stamnos, hydriai, and fragments of undetermined closed shapes. i. Vases, Greek—Catalogs. 2. Bareiss, Molly—Art collections—Catalogs. 3. Bareiss, Walter—Art collections—Catalogs. 4. Vases—Private collections— California—Malibu—Catalogs. 5. Vases—California— Malibu—Catalogs. 6. J. Paul Getty Museum—Catalogs. I. Clark, Andrew J., 1949- . II. J. Paul Getty Museum. III. Series: Corpus vasorum antiquorum. United States of America; fase. 23, etc. NK4640.C6.U5 fase. 23, etc. 73 8.3'82*0938074 s 88-12781 [NK4Ó24.B3 7] [73 8.3 '82J093 8074019493] ISBN 0-89236-134-4 © 1988 The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication -

Download Press Release

Exhibition facts Press conference 13 September 2012, 10:00am Opening 13 September 2012, 6:30pm Duration 14 September 2012 – 6 January 2013 Venue Bastion hall Curators Marie Luise Sternath and Eva Michel Catalogue Emperor Maximilian I and the Age of Dürer Edited by Eva Michel and Maria Luise Sternath, Prestel Publishing Autors: Manfred Hollegger, Eva Michel, Thomas Schauerte, Larry Silver, Werner Telesko, Elisabeth Thobois a.o. The catalogue is available in German and English at the Albertina Shop and at www.albertina.at for 32 € (German version) and 35 € (English version) Contact Albertinaplatz 1, A-1010 Vienna T +43 (0)1 534 83–0 [email protected] , www.albertina.at Museum hours daily 10:00am–6:00pm, Wednesdays 10:00am–9:00pm Press contact Mag. Verena Dahlitz (department head) T +43 (0)1 534 83-510, M +43 (0)699 121 78 720, [email protected] Mag. Barbara Simsa T +43 (0)1 534 83-512, M +43 (0)699 109 81 743, [email protected] Sarah Wulbrandt T +43 (0)1 534 83-511, M +43 (0)699 121 78 731, [email protected] The Albertina’s partners Exhibition sponsors Media partner Emperor Maximilian I and the Age of Dürer 14 September 2012 to 6 January 2013 Emperor Maximilian I was a "media emperor", who spared no efforts for the representation of his person and to secure his posthumous fame. He employed the best artists and made use of the most modern media of his time. Many of the most outstanding works produced for the propaganda and commemoration of Emperor Maximilian I are preserved in the Albertina. -

Art Concepts

ANCIENT ART - Greece Acropolis Greek, “high city.” In ancient Greece, usually the site of the city’s most important temple(s). Amphora A two-handled jar used for general storage purposes, usually to hold wine or oil. Archaic Smile In Archaic Greek sculpture, the smile sculptors represented on faces as a way of indicating that the person portrayed is alive. Atlant (Atlas) A male figure that functions as a supporting column. Black-Figure In early Greek pottery, the silhouetting of dark Painting figures against a light background of natural, reddish clay, with linear details incised through the silhouettes. Capital The uppermost member of a column, serving as a transition from the shaft to the lintel. In classical architecture, the form of the capital varies with the order. Caryatid A female figure that functions as a supporting column. Cella The chamber at the center of an ancient temple; in a classical temple, the room (Greek, naos) in which the cult statue usually stood. ANCIENT ART - Greece Centaur In ancient Greek mythology, a fantastical creature, with the front or top half of a human and the back or bottom half of a horse. Contrapposto The disposition of the human figure in which one part is turned in opposition to another part (usually hips and legs one way, shoulders and chest another), creating a counterpositioning of the body about its central axis. Sometimes called “weight shift” because the weight of the body tends to be thrown to one foot, creating tension on one side and relaxation on the other. Corinthian Corinthian columns are the latest of the three Greek styles and show the influence of Egyptian columns in their capitals, which are shaped like inverted bells.