A Case Study of the Weinstein Company, Harvey Weinstein, and the #Metoo Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexual Harassment Confession by Marianne M. Jennings

nepe-37-02-03 Page 7 PDF Created: 2018-5-31: 9:14:AM Ethics at Work Sexual Harassment Confession Silent bystanders extend the problem By Marianne M. Jennings, JD ©iStockphoto.com/jvannice knew enough to do more than I did" was the Power confession offered by Hollywood director Quentin The Weinstein type of behavior cannot continue unless the “ Tarantino to a New York Times reporter. He then gave individual involved is powerful. The most likely source of I specific examples of producer Harvey Weinstein’s that power is the ability to control employment. Employees behavior with named actresses and offered his assurance allow bad or illegal behaviors to happen or continue that he was not speaking of knowledge through gossip or without reporting or disclosing them because of their fear of secondhand information. In fact, his one-time girlfriend Mira retaliation. Sorvino had told him about Mr. Weinstein’s advances with her. An employee at a company once remarked to me that he He added that if he had done something, he would not have was unwilling to report issues of noncompliance because been able to work with Mr. Weinstein. Mr. Weinstein and Mr. “the first whale to the surface always gets harpooned.” When Tarantino had a close business relationship that brought a subordinate engages in illegal or inappropriate behavior, both financial success and critical acclaim. Mr. Weinstein we disclose the actions and take appropriate steps. When had referred to his production company as “the house that someone above us in the organization, political world, or Quentin built” with Pulp Fiction, Inglourious Basterds, and industry engages in illegal or inappropriate behavior, we note Django Unchained being their biggest hits. -

SHIRCORE Jenny

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd JENNY SHIRCORE - Make-Up and Hair Designer 2003 Women in Film Award for Best Technical Achievement Member of The Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences THE DIG Director: Simon Stone. Producers: Murray Ferguson, Gabrielle Tana and Ellie Wood. Starring: Lily James, Ralph Fiennes and Carey Mulligan. BBC Films. BAFTA Nomination 2021 - Best Make-Up & Hair KINGSMAN: THE GREAT GAME Director: Matthew Vaughn. Producer: Matthew Vaughn. Starring: Ralph Fiennes and Tom Holland. Marv Films / Twentieth Century Fox. THE AERONAUTS Director: Tom Harper. Producers: Tom Harper, David Hoberman and Todd Lieberman. Starring: Felicity Jones and Eddie Redmayne. Amazon Studios. MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS Director: Josie Rourke. Producers: Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner and Debra Hayward. Starring: Margot Robbie, Saoirse Ronan and Joe Alwyn. Focus Features / Working Title Films. Academy Award Nomination 2019 - Best Make-Up & Hairstyling BAFTA Nomination 2019 - Best Make-Up & Hair THE NUTCRACKER & THE FOUR REALMS Director: Lasse Hallström. Producers: Mark Gordon, Larry J. Franco and Lindy Goldstein. Starring: Keira Knightley, Morgan Freeman, Helen Mirren and Misty Copeland. The Walt Disney Studios / The Mark Gordon Company. WILL Director: Shekhar Kapur. Exec. Producers: Alison Owen and Debra Hayward. Starring: Laurie Davidson, Colm Meaney and Mattias Inwood. TNT / Ninth Floor UK Productions. Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 JENNY SHIRCORE Contd … 2 BEAUTY & THE BEAST Director: Bill Condon. Producers: Don Hahn, David Hoberman and Todd Lieberman. Starring: Emma Watson, Dan Stevens, Emma Thompson and Ian McKellen. Disney / Mandeville Films. -

136 NINE Der Regisseur Guido Contini Ist Ganz Oben

Berlinale 2010 Rob Marshall Birthday Special NINE NINE NINE USA 2009 Darsteller Guido Contini Daniel Day-Lewis Länge 118 Min. Carla Penélope Cruz Format 35 mm, Luisa Marion Cotillard Cinemascope Claudia Jenssen Nicole Kidman Farbe Lilli Judi Dench Mamma Sophia Loren Stabliste Stephanie Kate Hudson Regie Rob Marshall Saraghina Stacy Ferguson Buch Michael Tolkin Dante Ricky Tognazzi Anthony Fausto Giuseppe Cederna Minghella, Pierpaolo Elio Germano nach dem Musical Benito Andrea Di Stefano von Arthur Kopit Jaconelli Roberto Nobile und Maury Yeston, Assistenten Romina Carancini basierend auf Alessandro Federico Fellinis Denipotti Film 8 ½ Kamera Dion Beebe Schnitt Claire Simpson Wyatt Smith Judi Dench, Daniel Day-Lewis Ton Jim Greenhorn Musik Maury Yeston Musik-Supervision Matt Sullivan NINE Chroreografie Rob Marshall Der Regisseur Guido Contini ist ganz oben angekommen: Er gilt in den 60er John DeLuca Jahren als bester Filmemacher der Welt, hat dem italienischen Kino zu inter- Production Design John Myhre nationalem Glanz verholfen und wird von den schönsten Frauen der Welt Art Directors Peter Findley begehrt. Doch gerade, als er mit der Arbeit an seinem mit Span nung erwar- Phil Harvey Simon Lomont teten neuen Film beginnen will, stürzt er plötzlich tief in eine krea tive Le - Kostüm Colleen Atwood bens krise. Gleichermaßen verwirrt, verführt und angeregt von den Frauen Maske Peter King in seinem Leben – seiner Ehefrau Luisa, seiner Geliebten Carla, der amerika- Produzenten Rob Marshall nischen Mode-Journalistin Stephanie, seiner Kostüm de sig nerin Lilli, einer John DeLuca blonden Muse namens Claudia Jenssen, einer Jugendgeliebten und seiner Marc Platt Harvey Weinstein verstorbenen Mutter –, ringt er um Inspiration und Rettung. -

Nomination Press Release

Brian Boyle, Supervising Producer Outstanding Voice-Over Nahnatchka Khan, Supervising Producer Performance Kara Vallow, Producer American Masters • Jerome Robbins: Diana Ritchey, Animation Producer Something To Dance About • PBS • Caleb Meurer, Director Thirteen/WNET American Masters Ron Hughart, Supervising Director Ron Rifkin as Narrator Anthony Lioi, Supervising Director Family Guy • I Dream of Jesus • FOX • Fox Mike Mayfield, Assistant Director/Timer Television Animation Seth MacFarlane as Peter Griffin Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken: Star Wars Episode II • Cartoon Network • Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken: Star Wars ShadowMachine Episode II • Cartoon Network • Seth Green, Executive Producer/Written ShadowMachine by/Directed by Seth Green as Robot Chicken Nerd, Bob Matthew Senreich, Executive Producer/Written by Goldstein, Ponda Baba, Anakin Skywalker, Keith Crofford, Executive Producer Imperial Officer Mike Lazzo, Executive Producer The Simpsons • Eeny Teeny Maya, Moe • Alex Bulkley, Producer FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Corey Campodonico, Producer Century Fox Television Hank Azaria as Moe Syzlak Ollie Green, Producer Douglas Goldstein, Head Writer The Simpsons • The Burns And The Bees • Tom Root, Head Writer FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Hugh Davidson, Written by Century Fox Television Harry Shearer as Mr. Burns, Smithers, Kent Mike Fasolo, Written by Brockman, Lenny Breckin Meyer, Written by Dan Milano, Written by The Simpsons • Father Knows Worst • FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Kevin Shinick, -

Something Interesting Is Happening. Harvey Weinstein Was the King of Hollywood

Something interesting is happening. Harvey Weinstein was the king of Hollywood. The King. He was also a bully that used his male power and privilege to harass and abuse women. His behavior was allowed to persist for years. Until now. Someone said something, and then someone else said something. Suddenly, a bigger conversation is happening. Why did it take years, decades, so many women impacted? Why are there so many examples, just like this one, in the worlds of politics, sports, families, and corporate environments? Let's make sure we keep this conversation going. Meet the boys and girls from Maine. Thousands of young people in Maine have worked with Maine Boys to Men and could talk with Harvey about the realities of male power and privilege, what empathy and emotional connectedness with others means, why gender equity in relationships is a good thing for everybody. They could talk with The Men Who Kept Harvey Weinstein Safe about what it means to be an ally; to stand up with women and girls to stop these actions before they become violent. They could explain the power that bystanders have and describe specific ways to disrupt sexist, disrespectful, and abusive behaviors long before they get to this point. In short, Harvey and so many others could learn a lot from the boys and girls from Maine! The Proof. A recent evaluation of our middle school Reducing Sexism and Violence Program (RSVP), led by the University of New Hampshire, demonstrated a significant decrease in the endorsement of attitudes supporting male power and privilege, a self- reported increase in emotional awareness, and a significant increase in the endorsement of gender equity in relationships! Multiple 3rd party evaluations of RSVP for High School, including a two- year study by the Maine Center for Public Health, showed that RSVP changes attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs about sexism, sexual harassment, and gender-based violence. -

New York Women in Film & Television (Nywift)

NEW YORK WOMEN IN FILM & TELEVISION (NYWIFT) TO CELEBRATE EXCEPTIONAL WOMEN AT ST TH THE 41 ANNUAL NYWIFT MUSE AWARDS VIRTUALLY ON THURSDAY, DECEMBER 17 , 2020 GOLDEN GLOBE WINNING ACTRESS AWKWAFINA, TWO TIME GOLDEN GLOBE WINNING ACTRESS RACHEL BROSNAHAN, GRAMMY AWARD WINNING ACTRESS RASHIDA JONES, PULITZER PRIZE WINNING NEW YORK TIMES JOURNALISTS JODI KANTOR & MEGAN TWOHEY, PRESIDENT OF ORION PICTURES ALANA MAYO, AWARD-WINNING DIRECTOR GINA PRINCE-BYTHEWOOD, AND TONY AWARD-WINNING ACTRESS ALI STROKER TO RECEIVE HONORS NEW YORK, NY – NOVEMBER 30, 2020 – New York Women in Film & Television (NYWIFT) is proud to present ST the 41 Annual NYWIFT Muse Awards virtual event on Thursday, December 17, 2020. The event will be held virtually beginning at 1:00 PM ET and available for all those who register to watch on online at nywift.org/muse. This year’s theme is “Art & Advocacy,” as NYWIFT recognizes the role of the creative community in advancing positive social change. CBS Sunday Morning contributor, comedian, actress, and self-described “Accidental Pundette” Nancy Giles will again emcee the afternoon’s event, which celebrates women of outstanding vision and achievement both in front of and behind the camera in film, television, the music industry, and digital media. The honorees for this year’s Muse Awards are some of the most extraordinary women in the business: Awkwafina will receive a “Made in New York” Award from the Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment, for her contributions to NYC’s entertainment industry. She is a Golden Globe-winning actress from Queens, New York, who has used her trademark comedic style and signature flair to become a breakout talent. -

Discoveries, the Weinstein Company and Genius Products Debut an Adorable Story of Friendship, Love and Courage

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE JIM HENSON COMPANY: DISCOVERIES, THE WEINSTEIN COMPANY AND GENIUS PRODUCTS DEBUT AN ADORABLE STORY OF FRIENDSHIP, LOVE AND COURAGE Arriving on DVD September 2nd, Animated Family Adventure Features An All-Star Cast Of Voices Including Martin Short And Carl Reiner SANTA MONICA, CA – A lovable young elephant journeys into the big world when the CGI animated tale The Blue Elephant arrives on DVD September 2nd presented by The Weinstein Company, Genius Products and The Jim Henson Company: Discoveries, the newly formed acquisitions banner that presents third party produced titles that reflect the Company’s long-standing tradition of creative excellence. Produced in Thailand by Kantana Group Public Co. Ltd., The Blue Elephant features all-star voice talent including Emmy® Award winner* Martin Short (Spiderwick Chronicles, Santa Claus 3), eight time Emmy® Award winner** Carl Reiner (“Father of the Pride,” Ocean’s Thirteen) and Miranda Cosgrove (“iCarly,” “Drake & Josh”). A heartwarming film brimming with thrilling adventure, The Blue Elephant is a touching story with valuable life lessons as a young elephant encounters new friends, first love, and unexpected challenges. Fun for parents and kids alike, The Blue Elephant DVD will be available for the suggested retail price of $19.97. * 1983 – “SCTV” – Outstanding Writing in a Variety or Music Program ** 1957 & 1958 – “Caesar’s Hour” – Best Supporting Actor; 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966 – “The Dick Van Dyke Show” – Outstanding Writing Achievement in Comedy; 1995 – “Mad About You” – Outstanding Guest Actor in a Comedy Series Page 1 of 2 Synopsis: A young elephant goes on an extraordinary adventure and learns important lessons along the way about friendship, love and courage. -

Scandal, Social Movement, and Change: Evidence from #Metoo in Hollywood∗

Scandal, Social Movement, and Change: Evidence from #MeToo in Hollywood∗ Hong Luo† Laurina Zhang‡ First draft: April 24, 2020 Revised version: December 2, 2020 Abstract Social movements have the potential to effect change in strategic decision making. In this paper, we examine whether the #MeToo movement, spurred by the Harvey Weinstein scandal, leads to changes in the likelihood of Hollywood producers working with female writers on new movie projects. Since #MeToo affected the entire industry, we use variation in whether producers had past collaborations with Weinstein to investigate whether and how #MeToo may spur change. We find that producers previously associated with Weinstein are, on average, about 35-percent more likely to work with female writers after the scandal than they were before, relative to non-associated producers; and the size of this effect increases with the intensity of the association. Female producers are the main drivers of our results, perhaps because they are more likely than male producers to resonate with the movement’s cause and face relatively low costs of enacting change. Changes made by other groups, such as production teams with the most intense association with Weinstein and less-experienced all-male teams, may be better explained by motivations to mitigate risk. We also find that producers do not sacrifice writer experience by hiring more female writers and that both experienced and novice female writers have benefited from the increased demand. Our study shows that social movements that seek to address gender inequality can, indeed, lead to meaningful change. It also provides perspective for thinking about whether, and to what extent, changes may occur in broader settings. -

The Kings Speech: Based on the Recently Discovered Diaries of Lionel Logue Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE KINGS SPEECH: BASED ON THE RECENTLY DISCOVERED DIARIES OF LIONEL LOGUE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mark Logue,Peter J. Conradi | 352 pages | 01 May 2011 | Quercus Publishing | 9780857381118 | English | London, United Kingdom The Kings Speech: Based on the Recently Discovered Diaries of Lionel Logue PDF Book As the new king, Bertie is in a crisis when he must broadcast to Britain and the Empire following the declaration of war on Nazi Germany in For other uses, see King's speech. To achieve the effect, the lighting team erected huge blackout tents over the Georgian buildings and used large lights filtered through Egyptian cotton. May Data Protection Stupity - I normally desperately try to avoid any contact with any call centre unless I really have to and today's experiences remind me why. Danny Cohen. Music has to deal with time. Hooper employed a number of cinematic techniques to evoke the King's feelings of constriction. It isn't at all gossipy. Thomas J. California Chronicle. She asked him not to do so in her lifetime, and Seidler halted the project. Information Is Beautiful. Jersey election statistics - On 19 October Jersey will go to the polls to vote for Constables, Deputies and Senators on the same day for the first time. Jersey Blog. SophosLabs blog. What an excellent account of what Mr Logue achieved and how he helped with the kings speech problem. Logue wasn't a British aristocrat or even an Englishman - he was a commoner and an Australian to boot. The Daily Telegraph. All tracks are written by Alexandre Desplat , except where noted. -

Miramax's Asian Experiment: Creating a Model for Crossover Hits Lisa Dombrowski , Wesleyan University, US

Miramax's Asian Experiment: Creating a Model for Crossover Hits Lisa Dombrowski , Wesleyan University, US Prior to 1996, no commercial Chinese-language film had scored a breakout hit in the United States since the end of the 1970s kung fu craze. In the intervening period, the dominant distribution model for Asian films in America involved showcasing subtitled, auteur-driven art cinema in a handful of theaters in New York and Los Angeles, then building to ever more screens in a platform fashion, targeting college towns and urban theaters near affluent, older audiences. With the American fan base for Hong Kong action films steadily growing through video and specialized exhibition during the 1980s, Miramax chieftain Harvey Weinstein recognized the opportunity to market more commercial Chinese-language films to a wider audience outside the art cinema model as a means of generating crossover hits. Beginning in 1995, Weinstein positioned Miramax to become the primary distributor of Hong Kong action films in the United States. Miramax's acquisition and distribution strategy for Hong Kong action films was grounded in a specific set of assumptions regarding how to appeal to mass-market American tastes. The company targeted action-oriented films featuring recognizable genre conventions and brand- name stars, considering such titles both favorites of hardcore Hong Kong film fans and accessible enough to attract new viewers. Rather than booking its Hong Kong theatrical acquisitions into art cinemas, Miramax favored wide releases to multiplexes accompanied by marketing campaigns designed to highlight the action and hide the "foreignness" of the films. Miramax initially adopted a strategy of dubbing, re-scoring, re-editing, and often re-titling its Hong Kong theatrical and video/DVD releases in order to make them more appealing to mainstream American audiences. -

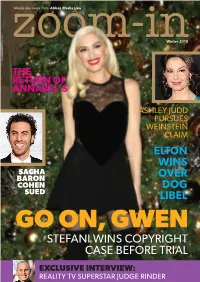

Zoom-In Issue 12

Media law news from Abbas Media Law zoom-inWinter 2018 THE RETURN OF ANNABEL’S ASHLEY JUDD PURSUES WEINSTEIN CLAIM ELTON WINS SACHA BARON OVER COHEN DOG SUED LIBEL GO ON, GWEN STEFANI WINS COPYRIGHT CASE BEFORE TRIAL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: REALITY TV SUPERSTAR JUDGE RINDER IN THIS ISSUE Geoffrey Rush gives evidence .........14 20 QUESTIONS Labour chief whip settles libel claim .14 Rob Rinder on how he brought his legal skills to TV ............................ 22 Mirror fails to strike out claim ..........15 Public interest defence wins on appeal .15 BUSINESS AFFAIRS & RIGHTS Abbas Media Law’s production legal schedule, setting out the five key stages of TV production and the legal issues producers must consider. In this issue, we focus on ‘fixer’ agreements ....... 16 COPYRIGHT & IP RIGHTS Rod Stewart sued over photo of WINNERS & LOSERS himself .........................................18 No trial for Stefani and Williams ........ 4 EU approves controversial directive .18 MEDIA HAUNTS Rebel Wilson damages appeal fails ... 4 It used to be THE place in London – is Netflix facing claim over Easy .........19 fabulous nightclub Annabel’s now back Payout for Elton John ...................... 4 New trial in Stairway to Heaven case ..20 on top? ...................................... 24 Property developer gets libel payout ... 6 Tracy Chapman sues Nicki Minaj ..... 20 Setback for Kendrick Lamar in video PRIVACY & DATA PROTECTION REGULATION – OFCOM, battle ..........................................21 Morrisons liable for data breach ..... 26 ASA & -

CINEMA the SHAPE of WATER: DREAMY DELIGHT Reelnews with GIRL-MEETS-FISHMAN ROMANCE

1 March 2018 DUBLIN GAZETTE 27 GAZETTE CINEMA THE SHAPE OF WATER: DREAMY DELIGHT ReelNews WITH GIRL-MEETS-FISHMAN ROMANCE WEINSTEIN WITHERS Studio facing bankruptcy It deserves AFTER weeks of turmoil and frantic behind the scenes efforts to save the studio, the Weinstein Co. is filing for bankruptcy. Ever since the infamous Harvey Weinstein scandal monstrous first emerged barely a blink ago, Weinstein Co. has been busy firefighting on all fronts, desperately trying to salvage the future of the previously respected New York film studio. success at The studio was already in some choppy waters – a series of underperfoming duds in recent years had tarnished its image, but the Weinstein scandal – and the the cinema explosion of the #MeToo movement – delivered a WITH the entire country ever stranger narrative crushing blow. currently going into near waters, twisting the narra- With lawsuits, criticisms meltdown over ‘The Beast tive into something darker of the board, firings and from The East’, why not and stranger than conven- Mute Elisa (Sally Hawkins) may seem a little eccentric, but her quiet demeanour restructuring, failures to take a break to consider tional film fare, yet in the masks a big heart, and an immutable determination to do what’s right – something secure financial lifelines The What-The in The process finding a deeply that an unlikely romance with a mysterious creature brings to the surface and so on, things looked Water instead? SHANE DILLON humane story, like a pearl increasingly bleak for the [email protected] I refer, of course, to the lost in the murk.