Field Techniques-Primates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Inventory of Avian Species in Aldesa Valley, Saudi Arabia

14 5 LIST OF SPECIES Check List 14 (5): 743–750 https://doi.org/10.15560/14.5.743 An inventory of avian species in Aldesa Valley, Saudi Arabia Abdulaziz S. Alatawi1, Florent Bled1, Jerrold L. Belant2 1 Mississippi State University, Forest and Wildlife Research Center, Carnivore Ecology Laboratory, Box 9690, Mississippi State, MS, USA 39762. 2 State University of New York, College of Environmental Science and Forestry, 1 Forestry Drive, Syracuse, NY, USA 13210. Corresponding author: Abdulaziz S. Alatawi, [email protected] Abstract Conducting species inventories is important to provide baseline information essential for management and conserva- tion. Aldesa Valley lies in the Tabuk Province of northwest Saudi Arabia and because of the presence of permanent water, is thought to contain high avian richness. We conducted an inventory of avian species in Aldesa Valley, using timed area-searches during May 10–August 10 in 2014 and 2015 to detect species occurrence. We detected 6860 birds belonging to 19 species. We also noted high human use of this area including agriculture and recreational activities. Maintaining species diversity is important in areas receiving anthropogenic pressures, and we encourage additional surveys to further identify species occurrence in Aldesa Valley. Key words Arabian Peninsula; bird inventory; desert fauna. Academic editor: Mansour Aliabadian | Received 21 April 2016 | Accepted 27 May 2018 | Published 14 September 2018 Citation: Alatawi AS, Bled F, Belant JL (2018) An inventory of avian species in Aldesa Valley, Saudi Arabia. Check List 14 (5): 743–750. https:// doi.org/10.15560/14.5.743 Introduction living therein (Balvanera et al. -

Recording Some of Breeding Birds in Mehmedan Region of Republic Yemen

Available online a t www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library European Journal of Experimental Biology, 2014, 4(1):625-632 ISSN: 2248 –9215 CODEN (USA): EJEBAU Recording some of breeding birds in Mehmedan region of Republic Yemen Fadhl Adullah Nasser Balem and Mohamed Saleh Alzokary Biology Department, Aden University, Yaman _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Mehmedan region is always green and there are different trees, shrubs, herbs and a lot of land which cultivated by corn, millet and other monetary plants. The site has been identified by the authors as an important Bird Area and especially for passerines breeding birds. Aim of this paper is to recording of some breeding birds.Many field visits during the year (2012) were conducted and (13) breeding bird species were recoded, these birds relating to (5) Orders, (10) Families, and (11) Genera. Key words: Breeding birds, Mehmedan, Yemen. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION At present time about (432) bird species were recorded in avifauna of Yemen of which (1) is endemic, (2) have been introduced by humans, and (25) are rare or accidental, (14) species are globally threatened.Mehmedan region located in southern Tehama which defined as lying south of (21 0N) along the Saudi Arabian and Yemen Red Sea lowlands and east along the Gulf of Aden to approximately (46 0E).Temperatures and humidity greatly increase southwards and rainfall decreases but the area has many permanent water courses and much subsurface water due to the considerable rub-off of rainwater from the highlands. Consequently there is much more vegetation in the wadis and there is a good deal of traditional, small scale agriculture mostly of millet, sorghum and vegetables[1]. -

Cascading Ecological Effects from Local Extirpation of an Ecosystem Engineer in the Arava Desert

This is a repository copy of Cascading ecological effects from local extirpation of an ecosystem engineer in the Arava desert. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/132128/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Shanas, U, Gavish, Y orcid.org/0000-0002-6025-5668, Bernheim, M et al. (3 more authors) (2018) Cascading ecological effects from local extirpation of an ecosystem engineer in the Arava desert. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 96 (5). pp. 466-472. ISSN 0008-4301 https://doi.org/10.1139/cjz-2017-0114 Copyright remains with the author(s) or their institution(s). This is an author produced version of a paper published in the Canadian Journal of Zoology. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Cascading ecological effects from local extirpation of an ecosystem engineer in the Arava desert Uri Shanasa,b, Yoni Gavishc, Mai Bernheimb, Shacham Mittlerb, Yael Olekb, Alon Tald a Department of Biology and Environment, University of Haifa Oranim, Tivon 36006, Israel. -

Elena C. Berg

ELENA C. BERG Department of Computer Science, Mathematics & Environmental Science The American University of Paris 6, rue du Colonel Combes 75007 Paris France Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.aup.edu/profile/eberg http://www.ioe.ucla.edu/ctr/staff/Berg_Elena.html CURRENT/RECENT POSITIONS Associate Professor, Department of Computer Science, Mathematics & Environmental Science, The American University of Paris, France, August 2016 – Present Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science, Mathematics & Environmental Science, The American University of Paris, France, January 2014 – July 2016 Senior Research Fellow, Center for Tropical Research, University of California, Los Angeles October 2006 – Present EDUCATION Ph.D., Animal Behavior, University of California, Davis. GPA: 4.0. June 2004. Fully funded through numerous grants, scholarships, and teaching assistantships Dissertation: Parentage, Kinship, and Group Structure in the White-throated Magpie-Jay (Calocitta formosa), a Cooperative Breeder with Female Helpers. Advisor: Dr. John Eadie Master of Philosophy, BiologiCal Anthropology, University of Cambridge, England. September 1996. Recipient of 1995 British Marshall Fellowship Thesis: Patterns of Rank-related Mating Success and Female Choice in Baboons and Macaques. Advisor: Dr. Phyllis Lee BaChelor of Arts, Anthropology anD College SCholar (interdisciplinary independent major), Cornell University, Ithaca, NY. GPA 3.9. May 1995. Junior Year Abroad, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany. 1993-1994. TEACHING & RESEARCH INTERESTS -

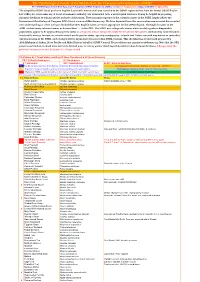

AERC Wplist July 2015

AERC Western Palearctic list, July 2015 About the list: 1) The limits of the Western Palearctic region follow for convenience the limits defined in the “Birds of the Western Palearctic” (BWP) series (Oxford University Press). 2) The AERC WP list follows the systematics of Voous (1973; 1977a; 1977b) modified by the changes listed in the AERC TAC systematic recommendations published online on the AERC web site. For species not in Voous (a few introduced or accidental species) the default systematics is the IOC world bird list. 3) Only species either admitted into an "official" national list (for countries with a national avifaunistic commission or national rarities committee) or whose occurrence in the WP has been published in detail (description or photo and circumstances allowing review of the evidence, usually in a journal) have been admitted on the list. Category D species have not been admitted. 4) The information in the "remarks" column is by no mean exhaustive. It is aimed at providing some supporting information for the species whose status on the WP list is less well known than average. This is obviously a subjective criterion. Citation: Crochet P.-A., Joynt G. (2015). AERC list of Western Palearctic birds. July 2015 version. Available at http://www.aerc.eu/tac.html Families Voous sequence 2015 INTERNATIONAL ENGLISH NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME remarks changes since last edition ORDER STRUTHIONIFORMES OSTRICHES Family Struthionidae Ostrich Struthio camelus ORDER ANSERIFORMES DUCKS, GEESE, SWANS Family Anatidae Fulvous Whistling Duck Dendrocygna bicolor cat. A/D in Morocco (flock of 11-12 suggesting natural vagrancy, hence accepted here) Lesser Whistling Duck Dendrocygna javanica cat. -

The Birds of the Highlands of South-West Saudi Arabia and Adjacent Parts of the Tihama: July 2010 (Abba Survey 42)

THE BIRDS OF THE HIGHLANDS OF SOUTH-WEST SAUDI ARABIA AND ADJACENT PARTS OF THE TIHAMA: JULY 2010 (ABBA SURVEY 42) by Michael C. Jennings, Amar R. H. Al-Momen and Jabr S. Y. Haresi December 2010 THE BIRDS OF THE HIGHLANDS OF SOUTH-WEST SAUDI ARABIA AND ADJACENT PARTS OF THE TIHAMA: JULY 2010 (ABBA SURVEY 42) by Michael C. Jennings1, Amar R. H. Al-Momen2 and Jabr S. Y. Haresi2 December 2010 SUMMARY The objective of the survey was to compare habitats and bird life in the Asir region, particularly Jebal Souda and the Raydah escarpment protected area of the Saudi Wildlife Commission, and adjacent regions of the tihama, with those observed in July 1987 (Jennings, et al., 1988). The two surveys were approximately the same length and equal amounts of time were spent in the highlands and on the tihama. A number of walked censuses were carried out during 2010 on Jebal Souda, using the same methodology as walked censuses in 1987, and the results are compared. Broadly speaking the comparison of censuses revealed that in 2010 there were less birds and reduced diversity on the Jebal Souda plateau, compared to 1987. However in the Raydah reserve the estimates of breeding bird populations compiled in the mid 1990s was little changed as far as could be assessed in 2010. The highland region of south-west Saudi Arabia, especially Jebal Souda, has been much developed since the 1987 survey and is now an important internal recreation and resort area. This has lead to a reduction in the region’s importance for terraced agriculture. -

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

Endocrine Correlates of Social and Reproductive Behaviours in a Group

ENDOCRINE CORRELATES OF SOCIAL AND REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOURS IN A GROUP-LIVING AUSTRALIAN PASSERINE, THE WHITE-BROWED BABBLER A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by Suzanne Oppenheimer B.A., M.A. Department of Biological Sciences 2005 i ABSTRACT To investigate the evolutionary rationale for the seemingly altruistic behaviours commonly seen in cooperatively breeding Australian passerines, I examined alloparental behaviour in the White-browed Babbler Pomatostomus superciliosus (WBBA). Toward this end, I analysed behavioural, hormonal, and genetic factors in both free-living and captive WBBAs. Studies of free-living birds examined social and reproductive behaviours and hormonal correlates to reproduction. With captive birds, I performed both observations and manipulative experiments focusing on intragroup social structure, social behaviours, and the endocrine correlates to such structure and behaviours. The WBBA was selected as a study species as they live in sedentary, year-round social groups that engage in cooperative breeding. Field work was conducted in Back Yamma State Forest, in the central west region of New South Wales, Australia. In this population of WBBAs, groups included many close genetic relatives, and neighboring groups also shared several related individuals. There were multiple breeding pairs within most groups, and reproductive behaviours between breeding pairs were similar to those of many biparentally breeding songbirds. However, nest defense and post- fledgling care were undertaken by large cooperative groups. In free-living WBBAs, plasma levels of testosterone (T), estradiol (E2), progesterone (P), prolactin (Prl), and corticosterone (B) were measured, and laparotomies were performed to ascertain gonadal condition. -

For Integrated Ecosystem Management in the Jordan Rift Valley

E1477 Public Disclosure Authorized The Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature Environmental and Social Assessment (ESA) and Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) for Integrated Ecosystem Management in the Jordan Rift Valley Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Final ESA and ESMP Report October 2nd, 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT (ESA) AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (ESMP) FOR INTEGRATED ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT IN THE JORDAN RIFT VALLEY PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Contents i List of Tables iv List of Figures vi Annexes vii Abbreviations viii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Project Background 1 1.2 Project and Environmental Assessment Objectives 2 1.3 Public Consultation 3 1.4 Supporting Maps 5 2 PROPOSED PROJECT 7 2.1 Project Location 8 2.2 Project Components 10 2.3 Sector Issues Addressed 20 2.4 Project Zones of Effect 21 2.5 Project Duration and Phases 23 2.6 Project Implementing Organization: Royal Society for Conservation of Nature 23 2.7 Project Benefits and Stakeholders 24 2.8 Project Sustainability 25 3 LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK 26 3.1 Introduction 26 3.2 Institutional Framework 27 3.2.1 Overview of Governmental Organizations 27 3.2.2 Universities and Research Institutes 37 3.2.3 Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) 39 3.3 National Agenda 41 3.4 Applicable National Environmental Legislations 42 3.4.1 Sources of Environmental Law in Jordan 42 3.4.2 Laws 51 3.4.3 Regulations (By-laws) 58 3.4.4 Strategies 62 3.4.5 Related Environmental -

Birdwatching in the United Arab Emirates

BIRDWATCHING IN THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES DIARY 961226 - 970109 Petter Haldén, Fredrik Malmaeus, Mikael Malmaeus, Mats Waern This is a try to write down the most important details of our trip to UAE. We had very good help from other people's travel reports made by Joakim Djerf, Tim Earl, Annika Forsten, Henk Hendriks and Erik Hirschfelt - we thank them. We hope that someone someday will have good help from this report. We also have to thank Colin Richardson who gave us useful information during the trip. Two books we used very much were Colin Richardson's "The Birds of the United Arab Emirates" and R F Porter, S Christensen and P Schiermacker-Hansen's "Field Guide to the Birds of the Middle East" (The excellent 1996 edition). Here follows a chronological view of what happened, which sites we visited, what birds we saw and perhaps some good advice. For a complete list of noted birds see the list of species at the end of the report. 961226. We arrived at Dubai airport around 4 p.m. At the airport we saw LAUGHING DOVE and PALLID SWIFT. We got our car, a little white Toyota, from Budget (195 dollars/week) immediatly at the airport and we drove to Dallas Hotel and checked in. Dallas Hotel was OK, situated in central Dubai. Most of the birding sites we visited during our trip were located one or two hours from Dubai, and therefore we found it suitable and convenient to stay at the same hotel during the whole trip. After checking in we took a walk down town. -

Intentional Presentation of Objects in Cooperatively Breeding Arabian Babblers (Turdoides Squamiceps)

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 09 April 2019 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2019.00087 Intentional Presentation of Objects in Cooperatively Breeding Arabian Babblers (Turdoides squamiceps) Yitzchak Ben Mocha 1,2,3* and Simone Pika 4,5 1 Research Group “Evolution of Communication”, Max Planck Institute for Ornithology, Seewiesen, Germany, 2 Department of Primatology, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany, 3 Centre for the Advanced Study of Collective Behaviour, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany, 4 Comparative BioCognition, Institute of Cognitive Science, University of Osnabrück, Osnabrück, Germany, 5 Center for Early Childhood Development and Education Research (CEDER), University of Osnabrück, Osnabrück, Germany The emergence of intentional communication and the intentional presentation of objects have been highlighted as important steps in the ontogeny of cooperative communication in humans. Furthermore, intentional object presentation has been suggested as an extremely rare form of communication evolutionarily. Research on comparable means of communication in non-human species may therefore shed light on the selection pressures that acted upon components of human communication. However, the functions and cognitive mechanisms that underlie object presentation in animals are poorly understood. Here, we addressed these issues by investigating Edited by: Elise Huchard, object presentations in wild, cooperative breeding Arabian babblers (Aves: Turdoides UMR5554 Institut des Sciences de squamiceps). Our results showed -

Mammal Diversity Survey in the Ibex Reserve, Saudi Arabia Tom Bruce

Mammal diversity survey in the Ibex Reserve, Saudi Arabia Final Report (2016) King Khalid Wildlife Research Centre (KKWRC), Saudi Wildlife Authority (SWA), Zoological Society of London (ZSL) Tom Bruce, Qais Saud al Hazzah, Othman Saad al Othman, Mohamed Hassan al Khairi, Torsten Wronski, Tim Wacher, Kevin Davey and Rajan Amin July 2016 Cover page images: Clockwise from top left: Nubian ibex Capra nubiana, Wadi Ghabah. Arabian gazelle Gazella arabica, Wadi Nukhailan. Arabian grey wolf Canis lupus arabs, Wadi Ghabah. Rüppell's fox Vulpes rueppellii, Wadi Nukhailan. Citation: Bruce, T1., Saud al Hazzah, Q2., Saad al Othman, O2., Hassan al Khairi, M3., Wronski, T3., Wacher, T1., Davey, K1. & Amin, R1. 2016. Mammal diversity survey in the Ibex Reserve, Saudi Arabia. Final report 2016. Zoological Society of London. ii + 52 pp. 1Zoological Society of London, Regents Park, London, NW1 4RY. 2Saudi Wildlife Authority, Riyadh 11575, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 3King Khalid Wildlife Research Center, Thumamah, P.O Box 61681, Riyadh 11575, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Contents Summary 1 1. Introduction 2 2. Methods 3-6 3. Results 7-11 4. Species Reports 12 Ungulates 1) Nubian ibex 12-13 2) Arabian gazelle 14-15 Carnivores 3) Arabian wolf 16-17 4) Blanford’s fox 18-19 5) Rüppell's fox 20-21 6) Arabian red fox 22-23 7) Vulpes sp. 24-25 8) Wild cat 26-27 Lagomorphs 9) Cape hare 28-29 Hyraciodea 10) Rock hyrax 30-31 Eulipotyphla 11) Desert hedgehog 32-33 Muridae 12) Bushy-tailed jird 34-35 13) Arabian spiny mouse 36-37 14) Rodent species 38-39 Domestic Ungulates 15) Dromedary camel 40-41 16) Donkey 42-43 17) Shoat 44-45 Mustiledae 18) Honey badger 46 5.