Evidence-Based Strategies to Combat Scientific Misinformation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tracing Climate Change Denial in the United States and Looking for Impacts on the United States’ Science Diplomacy

CENTRE INTERNATIONAL DE FORMATION EUROPEENNE SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT INSTITUT EUROPEEN · EUROPEAN INSTITUTE Tracing Climate Change Denial in the United States and Looking for Impacts on the United States’ Science Diplomacy By Stephanie Baima A thesis submitted for the Joint Master degree in Global Economic Governance & Public Affairs (GEGPA) Academic year 2019 – 2020 July 2020 Supervisor: Hartmut Marhold Reviewer: Christian Blasberg PLAGIARISM STATEMENT I certify that this thesis is my own work, based on my personal study and/or research and that I have acknowledged all material and sources used in its preparation. I further certify that I have not copied or used any ideas or formulations from any book, article or thesis, in printed or electronic form, without specifically mentioning their origin, and that the complete citations are indicated in quotation marks. I also certify that this thesis has not previously been submitted for assessment in any other unit, except where specific permission has been granted from all unit coordinators involved, and that I have not copied in part or whole or otherwise plagiarized the work of other students and/or persons. In accordance with the law, failure to comply with these regulations makes me liable to prosecution by the disciplinary commission and the courts of the French Republic for university plagiarism. Stephanie Baima 10 July 2020 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................ 3 Abstract -

Global Warming 101: Science | Globalwarming.Org Page 1 of 11

Global Warming 101: Science | GlobalWarming.org Page 1 of 11 OpenMarket.org Podcast GlobalWarming.org Facts About Ethanol Control Abuse of Power Enter your search keywords here... Blog Features Kyoto Negotiations Politics Science Small business Students videos Cooler Heads Digest Events Global Warming 101 Categorized | Global Warming 101 Global Warming 101: Science by William Yeatman February 03, 2009 @ 3:46 pm ShareThis PrintThis EmailThis Global Warming 101: Science A “planetary emergency—a crisis that threatens the survival of our civilization and the habitability of the Earth ”—that is how former Vice President Al Gore describes global warming. Most environmental http://www.globalwarming.org/2009/02/03/global -warming -101 -science/ 2/22/2010 Global Warming 101: Science | GlobalWarming.org Page 2 of 11 groups preach the same message. So do many journalists. So do some scientists. In fact, at the 2008 annual meeting of Nobel Prize winners in Lindau, Germany , half the laureates on the climate change panel disputed the so-called consensus on global warming. greenhouseeffectpreview The Greenhouse Effect You have probably heard the dire warnings many times. Carbon dioxide (CO2) from mankind’s use of fossil fuels like coal, oil, and natural gas is building up in the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas—it traps heat that would otherwise escape into outer space. Al Gore warns that global warming caused by carbon dioxide emissions could increase sea levels by 20 feet, spin up deadly hurricanes. It could even plunge Europe into an ice age. Science does not support these and other scary predictions, which Gore and his allies repeatedly tout as a “scientific consensus.” Global warming is real and carbon dioxide emissions are contributing to it, but it is not a crisis. -

The Informational Context of Climate Change Polarization

1 Supplementary Materials for Party Elites or Manufactured Doubt? The Informational Context of Climate Change Polarization Sample Construction and Dictionaries We downloaded transcripts and articles if they had reference to either global warming or climate change in both the body of the text and Lexis’s or Factiva’s subject tags. They were further limited to those that had a geography tag indicating that the story contains some focus on the United States. Unfortunately, the subject tags are error prone, so we used a combination of manual coding and machine learning to ensure the sample only included relevant articles and transcripts We manually coded the sample of broadcast transcripts identified as having Republican and Democratic cues for relevance. We also coded a sample of 500 articles each from three time periods: 1980-1997, 1998-2005, and 2006-2014. Coders marked a story as relevant if a segment of the transcript or article was about climate science, climate change impacts, or policy aimed at addressing climate change. This excluded articles that made only passing references to climate change. We then used R Text Tools, an R package that assembles nine machine learning algorithms, to code the remaining articles for relevance. Algorithms were trained on each time period sample independently, and applied to the remaining articles for a given period. In doing so, we hoped to maintain algorithm accuracy over time as the salience of climate change and the nature of its coverage changed over time. Agreement on topic relevance between the machine results and manual coding for validation was approximately 90 percent for newspapers across all three time periods, and between 84 and 96 percent for broadcast transcripts that lacked the presence of party cues. -

Senate Media Advisory and Schedule

July 11, 2016 Contact: Rich Davidson (202) 228-6291 (press office) *** MEDIA ADVISORY *** Senators to Expose Web of Denial Blocking Action on Climate Follow #WebOfDenial and #TimeToCallOut Washington, DC – Today, Monday, from 4:45 p.m. to 6:45 p.m., tomorrow, Tuesday, from 5 p.m. to 7:30 p.m., and throughout the week,* 19 Senators will take to the Senate floor to call out Koch brothers- and fossil fuel industry-funded groups that have fashioned a web of denial to block action on climate change. Despite polling that shows over 80 percent of Americans favor action to reduce carbon pollution, Congress has failed to pass comprehensive climate legislation. The Senators will each deliver remarks detailing how interconnected groups – funded by the Koch brothers, major fossil fuel companies like ExxonMobil and Peabody Coal, identity-scrubbing groups like Donors Trust and Donors Capital, and their allies – developed and executed a massive campaign to deceive the public about climate change to halt climate action and protect their bottom lines. As part of their effort to draw attention to the web of denial, Senators Whitehouse, Markey, Schatz, Boxer, Merkley, Warren, Sanders, and Franken are introducing a resolution describing and condemning the efforts of corporations and groups to mislead the public about the harmful effects of tobacco, lead, and climate. The resolution also urges fossil fuel corporations and their allies to cooperate with investigations into their climate-related activities. Congressman Ted Lieu (D-CA) is introducing the resolution in the House this week. Use #WebOfDenial and #TimetoCallOut to follow the speeches on Twitter. -

Supplementary Online Material Table of Contents S-1

Supplementary Online Material Table of Contents S-1 Coding Instructions – U.S. National Climate Counter-movement Organizations 2 S-2 Coding Sheet – U.S. National Climate Counter-movement Organizations 3 S-3 U.S. National Climate Counter-movement Organizations 4 S-4 U.S. National Climate Change Counter-movement Income Data 2003 – 2010 5 S-5 U.S. National Climate Change Counter-movement Income Distribution 2003 – 2010 36 S-6 Foundation Funding of U.S. National Climate Counter-movement By Foundation and Year 39 S-7 .Foundation Funding of U.S. National Climate Counter-movement By Organization and Year 43 S-8 Foundation Funding of U.S. National Climate Counter-movement Organizations – By Foundation 45 S-9 Foundation Funding of U.S. National Climate Counter-movement Organizations – By Recipient 79 S 10 Climate Change Counter-movement Network Dimensions 113 S 11 Climate Change Counter-movement Network - Relative Node Strength 114 S 12 Climate Change Counter-movement Network - Relative Node Degree 115 Figure S-1 116 Methods Appendix 117 1 S-1 Coding Instructions – U.S. National Climate Counter-movement Organizations The purpose of this organizational coding is to identify the organizations that make up the climate counter-movement in the United States. Definition of climate counter-movement – organizations that advocate against government policies to take substantive action to mitigate climate change. Specifically, this movement opposes mandatory restrictions on GHG emissions, either through regulations or a carbon fee. The advocacy of this community contains several different arguments, such as: 1. Climate change is not occurring. 2. Climate change is occurring, but it is not due to humans. -

Climate Change

2 0 0 8 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CLIMATE CHANGE THE 2008 INTERNATIONAL C O N F E R E N C E O N CLIMATE CHANGE Can you hear us now? Global Warming is not a crisis! SPONSORED BY THE HEARTLAND INSTITUTE March 2 - 4, 2008 · New York1 City · The Marriott Marquis 2 0 0 8 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CLIMATE CHANGE HOST COSPONSORS Alternate Solutions Institute Committee for a Constructive Tomorrow Instituto Liberdade Pakistan United States Brazil Americans for Prosperity Competitive Enterprise Institute International Climate Science Coalition United States United States Canada - Australia - New Zealand Americans for Tax Reform Congress of Racial Equality International Policy Network United States United States United Kingdom Asociacion de Consumidores Libres Discovery Institute Istituto Bruno Leoni Costa Rica United States Italy Association for Liberal Thinking Doctors for Disaster Preparedness JunkScience.com Turkey United States United States Business & Media Institute Economic Thinking Liberty Institute United States United States India Carbon Sense Coalition European Center for Economic Growth Lion Rock Institute Australia United Kingdom Hong Kong Capital Research Center Freedom Foundation of Minnesota John Locke Foundation United States United States United States Cascade Policy Institute Free Enterprise Action Fund George C. Marshall Institute United States United States United States Cathay Institute for Public Affairs Free Market Foundation Minimal Government Institute China South Africa Philippines Center for the Defense of Free Enterprise -

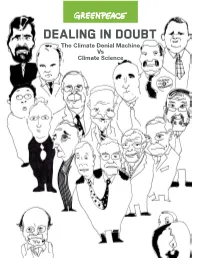

DEALING in DOUBT the Climate Denial Machine Vs Climate Science Dealing in Doubt Greenpeace USA, 2013 Page 2

DEALING IN DOUBT The Climate Denial Machine Vs Climate Science Dealing in Doubt Greenpeace USA, 2013 page 2 Dealing in Doubt The climate denial machine vs climate science a brief history of attacks on climate science, climate scientists and the IPCC Published by: Greenpeace USA September 2013 All Illustrations: © Greenpeace USA “Doubt is our product, since it is the best means of competing with the ‘body of fact’ [linking smoking with disease] that exists in the mind of the general public. It is also the means of establishing a controversy...” Tobacco company Brown and Williamson internal document, 19691 “Skepticism is not believing what someone tells you, investigating all the information before coming to a conclusion. Skepticism is a good thing. Global warming skepticism is not that. It’s the complete opposite of that. It’s coming to a preconceived conclusion and cherry-picking the information that backs up your opinion. Global warming skepticism isn’t skepticism at all.” —John Cook of Skepticalscience.com2 1 http://tobaccodocuments.org/landman/332506.html 2 http://news.discovery.com/earth/a-conversation-with-a-genuine-skeptic.html Dealing in Doubt Greenpeace USA, 2013 page 3 DEALING in doubt DEALING IN DOUBT Introduction 6 Meanwhile the consensus – and evidence – continues to grow 7 Part 1: A brief history of denial 8 The 1990s: a network of denial is created 8 The funders: 9 ExxonMobil 9 The Koch Brothers 9 Donors Trust & Donors Capital: The ATM of Climate Denial 10 The Players 11 Climate denial’s “continental army” 11 The think tanks -

Climate Change Counter Movement Neutralization Techniques: a Typology to Examine the Climate Change Counter Movement*

Climate Change Counter Movement Neutralization Techniques: A Typology to Examine the Climate Change Counter Movement* Ruth E. McKie , De Montfort University The Climate Change Counter Movement has been a topic of interest for social sci- entists and environmentalists for the past 25 years (Dunlap and McCright, 2015). This research uses the sociology of crime and deviance to analyze the numerous arguments used by climate change counter movement organizations. Content analysis of 805 state- ments made by climate change counter movement organizations reveals that the theory Techniques of Neutralization (Sykes and Matza, American Sociological Review 22 (6):664, 1957) can help us better understand the arguments adopted by these organiza- tions. Taking two observations from two time points, the author examine not only the composition of the messaging adopted by Climate Change Counter Movement (CCCM) organization, but how these messages have changed over time. In all, there were 1,435 examples of CCCM neutralization techniques adopted by CCCM organizations across these two points in time. This examination of the movement provides valuable insight into the CCCM and the subsequent environmental harm that is partly facilitated by their actions. Introduction Climate change is one of the most pressing issues facing the world (Pachauri et al. 2014). Industrial and technological developments have increased the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases (GHGs) creating what scientists have documented as a warming of the Earth’s atmosphere (e.g., Mann et al. 2017). The adverse effects of climate change will likely cause mass victimization of varying forms (Popovski and Mundy 2012), including public health effects such as heat-related illnesses, waterborne and foodborne diseases (Patz et al.