Honthorst, Gerrit Van Also Known As Honthorst, Gerard Van Gherardo Della Notte Dutch, 1590 - 1656

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![1622] Bartolomeo Manfredi](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4679/1622-bartolomeo-manfredi-824679.webp)

1622] Bartolomeo Manfredi

動としてのカラヴァジズムがローマに成 立したのである。註1) バルトロメオ・マンフレーディ[オスティアーノ、 1582 ― ローマ、1622] 本作品は2002年にウィーンで「マンフレーディの周辺の画家」の 《 キリスト捕 縛 》 作として競売にかけられ世に出た。註 2) その後修復を経て2004年、 1613–15 年頃 油 彩 、カ ン ヴ ァ ス 研究者ジャンニ・パピによって「マンフレーディの最も重要な作品の 120×174 cm ひ と つ 」と し て 紹 介 さ れ ( Papi 2004)、 ハ ー テ ィ エ ( Hartje 2004)お よ Bartolomeo Manfredi [Ostiano, 1582–Rome, 1622] The Capture of Christ び パ ピ( Papi 2013)のレゾネに真筆として掲載されたほか、2005–06 c. 1613–15 年にミラノとウィーンで開かれた「カラヴァッジョとヨーロッパ」展など Oil on canvas 註 3) 120×174 cm にも出 品された。 P.2015–0001 キリストがオリーヴ山で祈りをささげた後、ユダの裏切りによって 来歴/ Provenance: James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton (1606–1649), Scotland, listed in Inventories of 1638, 1643 and 1649; Archduke Leopold 捕縛されるという主題は、四福音書すべてに記されている(たとえば Wilhelm (1614–1662) from 1649, Brussels, then Vienna, listed in Inventories マタイ 26:47–56)。 銀 貨 30枚で買収されたユダは、闇夜の中誰がイ of 1659, 1660; Emperor Leopold I, Vienna, listed in Inventory of 1705; Emperor Charles VI, Stallburg, Vienna, listed in List of 1735; Anton Schiestl, エス・キリストであるかをユダヤの祭司長に知らせる合図としてイエ Curate of St. Peter’s Church, before 1877, Vienna; Church of St. Stephen, Baden, Donated by Anton Schiestl in 1877; Sold by them to a Private スに接吻をしたのである。マンフレーディの作品では、甲冑をまとった Collection, Austria in 1920 and by descent; Sold at Dorotheum, Vienna, 2 兵士たちに囲まれ、赤い衣をまとったキリストが、ユダから今にも裏 October 2002, lot 267; Koelliker Collection, Milan; purchased by NMWA in 2015. 切りの接吻を受けようとしている。キリストは僅かに視線を下に落と 展覧会歴/ Exhibitions: Milan, Palazzo Reale / Vienna, Liechtenstein し、抵抗するでもなく自らの運 命を受け入 れるかのように静 かに両 手 Museum, Caravaggio e l’Europa: Il movimento caravaggesco internazionale da Caravaggio a Mattia Preti, 15 October 2005–6 February 2006 / 5 を広げている。 March 2006–9 July 2006, no. -

Honthorst, Gerrit Van Also Known As Honthorst, Gerard Van Gherardo Della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Honthorst, Gerrit van Also known as Honthorst, Gerard van Gherardo della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656 BIOGRAPHY Gerrit van Honthorst was born in Utrecht in 1592 to a large Catholic family. His father, Herman van Honthorst, was a tapestry designer and a founding member of the Utrecht Guild of St. Luke in 1611. After training with the Utrecht painter Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), Honthorst traveled to Rome, where he is first documented in 1616.[1] Honthorst’s trip to Rome had an indelible impact on his painting style. In particular, Honthorst looked to the radical stylistic and thematic innovations of Caravaggio (Roman, 1571 - 1610), adopting the Italian painter’s realism, dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, bold colors, and cropped compositions. Honthorst’s distinctive nocturnal settings and artificial lighting effects attracted commissions from prominent patrons such as Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577–1633), Cosimo II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany (1590–1621), and the Marcheses Benedetto and Vincenzo Giustiniani (1554–1621 and 1564–1637). He lived for a time in the Palazzo Giustiniani in Rome, where he would have seen paintings by Caravaggio, and works by Annibale Carracci (Bolognese, 1560 - 1609) and Domenichino (1581–-1641), artists whose classicizing tendencies would also inform Honthorst’s style. The contemporary Italian art critic Giulio Mancini noted that Honthorst was able to command high prices for his striking paintings, which decorated -

Mise En Page 1

Nobiltà e bassezze mai potuto ricevere un tale riconoscimento a causa dei suoi trascorsi criminali, ricorse all’espediente di farsi chiamare cava - nella biografia liere dai propri associati, anche se non lo era affatto. Inoltre affittò una lussuosa dimora nelle immediate vicinanze di piazza del dei pittori di genere Popolo e girava in carrozza, perché a Roma l’apparire era impor - tante per la carriera. Da Roma, infatti, Artemisia Gentileschi e il Patrizia Cavazzini marito sollecitarono a più riprese la spedizione dei corami d’oro, abbandonati dalla coppia a Firenze quando erano fuggiti per debiti, “perché qua bisogna stare con gran decoro.” Il desiderio di riconoscimento sociale da parte degli artisti era esplicitamente dichiarato in una commedia, recitata da vari di loro a casa dei conti Soderini durante il carnevale del 1634 e intitolata La pittura esaltata, in cui si narrava di un principe che sceglieva un pittore come sposo per la figlia. In realtà molti artisti si muovevano tra due mondi, quello dei raffinati committenti, ma anche uno fatto di taverne, giochi di carte, risse di strada e ubriacature, in cui i protagonisti erano osti e prostitute, non certo nobili e cardinali. Giovanni Lanfranco da Napoli, nel 1637, scri - Spesso i biografi degli artisti tendono a raccontarci gli aspetti più veva con un certo rammarico a Ferrante Carlo che nella città edificanti della loro vita, a cominciare dai loro rapporti con i partenopea non frequentava osterie e neppure si incontrava committenti di più alto livello sociale. Ad esempio Filippo sovente con amici e colleghi “perché costì non usa”, evidente - Baldinucci sottolinea come Gian Lorenzo Bernini, il vero artista mente al contrario di Roma. -

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 09, Issue 06, 2020: 01-11 Article Received: 26-04-2020 Accepted: 05-06-2020 Available Online: 13-06-2020 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v9i6.1920 Caravaggio and Tenebrism—Beauty of light and shadow in baroque paintings Andy Xu1 ABSTRACT The following paper examines the reasons behind the use of tenebrism by Caravaggio under the special context of Counter-Reformation and its influence on later artists during the Baroque in Northern Europe. As Protestantism expanded throughout the entire Europe, the Catholic Church was seeking artistic methods to reattract believers. Being the precursor of Counter-Reformation art, Caravaggio incorporated tenebrism in his paintings. Art historians mostly correlate the use of tenebrism with religion, but there have also been scholars proposing how tenebrism reflects a unique naturalism that only belongs to Caravaggio. The paper will thus start with the introduction of tenebrism, discuss the two major uses of this artistic technique and will finally discuss Caravaggio’s legacy until today. Keywords: Caravaggio, Tenebrism, Counter-Reformation, Baroque, Painting, Religion. This is an open access article under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. 1. Introduction Most scholars agree that the Baroque range approximately from 1600 to 1750. There are mainly four aspects that led to the Baroque: scientific experimentation, free-market economies in Northern Europe, new philosophical and political ideas, and the division in the Catholic Church due to criticism of its corruption. Despite the fact that Galileo's discovery in astronomy, the Tulip bulb craze in Amsterdam, the diplomatic artworks by Peter Paul Rubens, the music by Johann Sebastian Bach, the Mercantilist economic theories of Colbert, the Absolutism in France are all fascinating, this paper will focus on the sophisticated and dramatic production of Catholic art during the Counter-Reformation ("Baroque Art and Architecture," n.d.). -

1 Caravaggio and a Neuroarthistory Of

CARAVAGGIO AND A NEUROARTHISTORY OF ENGAGEMENT Kajsa Berg A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia September 2009 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior written consent. 1 Abstract ABSTRACT John Onians, David Freedberg and Norman Bryson have all suggested that neuroscience may be particularly useful in examining emotional responses to art. This thesis presents a neuroarthistorical approach to viewer engagement in order to examine Caravaggio’s paintings and the responses of early-seventeenth-century viewers in Rome. Data concerning mirror neurons suggests that people engaged empathetically with Caravaggio’s paintings because of his innovative use of movement. While spiritual exercises have been connected to Caravaggio’s interpretation of subject matter, knowledge about neural plasticity (how the brain changes as a result of experience and training), indicates that people who continually practiced these exercises would be more susceptible to emotionally engaging imagery. The thesis develops Baxandall’s concept of the ‘period eye’ in order to demonstrate that neuroscience is useful in context specific art-historical queries. Applying data concerning the ‘contextual brain’ facilitates the examination of both the cognitive skills and the emotional factors involved in viewer engagement. The skilful rendering of gestures and expressions was a part of the artist’s repertoire and Artemisia Gentileschi’s adaptation of the violent action emphasised in Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes testifies to her engagement with his painting. -

TASTE and PRUDENCE in the ART of JUSEPE DE RIBERA by Hannah Joy Friedman a Dissertation Submitted to the Johns Hopkins Universit

TASTE AND PRUDENCE IN THE ART OF JUSEPE DE RIBERA by Hannah Joy Friedman A dissertation submitted to the Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland May, 2016 Copyright Hannah Joy Friedman, 2016 (c) Abstract: Throughout his long career in southern Italy, the Spanish artist Jusepe de Ribera (1591- 1652) showed a vested interest in the shifting practices and expectations that went into looking at pictures. As I argue, the artist’s evident preoccupation with sensory experience is inseparable from his attention to the ways in which people evaluated and spoke about art. Ribera’s depictions of sensory experience, in works such as the circa 1615 Five Senses, the circa 1622 Studies of Features, and the 1637 Isaac Blessing Jacob, approach the subject of the bodily senses in terms of evaluation and questioning, emphasizing the link between sensory experience and prudence. Ribera worked at a time and place when practices of connoisseurship were not, as they are today, a narrow set of preoccupations with attribution and chronology but a wide range of qualitative evaluations, and early sources describe him as a tasteful participant in a spoken connoisseurial culture. In these texts, the usage of the term “taste,” gusto, links the assessment of Ribera’s work to his own capacity to judge the works of other artists. Both taste and prudence were crucial social skills within the courtly culture that composed the upper tier of Ribera’s audience, and his pictures respond to the tensions surrounding sincerity of expression or acceptance of sensory experience in a novel and often satirical vein. -

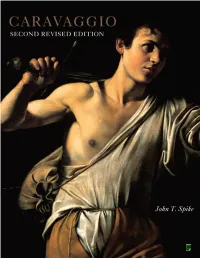

Caravaggio, Second Revised Edition

CARAVAGGIO second revised edition John T. Spike with the assistance of Michèle K. Spike cd-rom catalogue Note to the Reader 2 Abbreviations 3 How to Use this CD-ROM 3 Autograph Works 6 Other Works Attributed 412 Lost Works 452 Bibliography 510 Exhibition Catalogues 607 Copyright Notice 624 abbeville press publishers new york london Note to the Reader This CD-ROM contains searchable catalogues of all of the known paintings of Caravaggio, including attributed and lost works. In the autograph works are included all paintings which on documentary or stylistic evidence appear to be by, or partly by, the hand of Caravaggio. The attributed works include all paintings that have been associated with Caravaggio’s name in critical writings but which, in the opinion of the present writer, cannot be fully accepted as his, and those of uncertain attribution which he has not been able to examine personally. Some works listed here as copies are regarded as autograph by other authorities. Lost works, whose catalogue numbers are preceded by “L,” are paintings whose current whereabouts are unknown which are ascribed to Caravaggio in seventeenth-century documents, inventories, and in other sources. The catalogue of lost works describes a wide variety of material, including paintings considered copies of lost originals. Entries for untraced paintings include the city where they were identified in either a seventeenth-century source or inventory (“Inv.”). Most of the inventories have been published in the Getty Provenance Index, Los Angeles. Provenance, documents and sources, inventories and selective bibliographies are provided for the paintings by, after, and attributed to Caravaggio. -

Dirck Van Baburen and the “Self-Taught” Master, Angelo Caroselli

Volume 5, Issue 2 (Summer 2013) Dirck van Baburen and the “Self-Taught” Master, Angelo Caroselli Wayne Franits Recommended Citation: Wayne Franits, “Dirck van Baburen and the “Self-Taught” Master, Angelo Caroselli” JHNA 5:2 (Summer 2013), DOI:10.5092/jhna.2013.5.2.5 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/dirck-van-baburen-self-taught-master-angelo-caroselli/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This is a revised PDF that may contain different page numbers from the previous version. Use electronic searching to locate passages. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 5:2 (Summer 2013) 1 DIRCK VAN BABUREN AND THE “SELF-TAUGHT” MASTER, ANGELO CAROSELI Wayne Franits During his approximately eight-year stay in Rome, the noted Utrecht Caravaggist, Dirck van Baburen, responded to the work of some of the Eternal City’s most influential painters. It has long been known, for example, that Van Baburen appropriated motifs and pictorial devices from such eminent Italian artists as Caravaggio and Bartolomeo Manfredi as well as the Spaniard, Jusepe de Ribera. The present essay argues that the art of the little-known Italian master, Angelo Caroselli, also exerted a formidable impact upon the Dutchman, particularly the latter’s portrayal of genre subjects produced after his return to his native Utrecht. 10.5092/jhna.2013.5.2.5 1 n the course of conducting research for my recent monograph on Dirck van Baburen (ca. -

Two Netherlandish Painters in Naples Between 1598 and 1612: Louis Finson and Abraham Vinck

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Netherlandish immigrant painters in Naples (1575-1654): Aert Mytens, Louis Finson, Abraham Vinck, Hendrick De Somer and Matthias Stom Osnabrugge, M.G.C. Publication date 2015 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Osnabrugge, M. G. C. (2015). Netherlandish immigrant painters in Naples (1575-1654): Aert Mytens, Louis Finson, Abraham Vinck, Hendrick De Somer and Matthias Stom. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:02 Oct 2021 CHAPTER TWO TWO NETHERLANDISH PAINTERS IN NAPLES BETWEEN 1598 AND 1612: LOUIS FINSON AND ABRAHAM VINCK The previous chapter offered an account of an individual career, to nuance Van Mander’s ideas about the Italian journey. -

Some Seventeenth-Century Appraisals of Caravaggio's Coloring Author(S): Janis C

Some Seventeenth-Century Appraisals of Caravaggio's Coloring Author(s): Janis C. Bell Source: Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 14, No. 27 (1993), pp. 103-129 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483447 Accessed: 01-04-2019 18:32 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae This content downloaded from 79.131.76.118 on Mon, 01 Apr 2019 18:32:01 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JANIS C. BELL Some Seventeenth-Century Appraisals of Caravaggio's Coloring Introduction the history of painting in Rome in the late Cinquecento, he contrasted the "weak and whitewashed" coloring of the Writing less than a decade after Caravaggio's death, Giulio Mannerists and the "immaginary and faint" colors of Giuseppe Mancini opened his biography of the artist with a statement Cesari d'Arpino with Caravaggio's "real and true-to-life" colo- about the importance of Caravaggio's color: "Our age owes ration (reale e vero).5 Clearly, Caravaggio's coloring was one much to Michelangelo da Caravaggio for the coloring (colorir) of the principal features of his art, perhaps the most signifi- that he introduced, which is now widely followed."' While the cant. -

Copp Catherine E 201405

“THE CARRACCI AND VENICE: ANNIBALE CARRACCI’S STYLISTIC RESPONSE TO VENETIAN ART, AND THE INTERMEDIATE ROLES OF LUDOVICO AND AGOSTINO CARRACCI by Catherine E. Copp A thesis submitted to the Department of Art History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (May, 2014) Copyright © Catherine E. Copp, 2014 Abstract It has always been acknowledged that Venetian art was one of the components from which Annibale Carracci formed his painting style. There is little documentary evidence concerning Annibale’s career and no Venetian sources to inform us of his contact with Venice. Taking his art as the primary source, this study examines the timing and nature of Annibale’s contact with Venetian art and artists. It also investigates the works of his brother Agostino and his cousin Ludovico to discover their roles in directing Annibale towards Venetian art and communicating its qualities to him. The working method used is comparative analysis between Annibale’s art and key paintings he could have seen in Venice and North Italian collections. Sources such as the early biographies and the marginal comments in the Carracci’s copy of Vasari’s Vite supplement the primary artistic evidence. This study compiles and critically engages with analyses from previous scholarship. The thesis investigates the role of prints in the early orientation of the Carracci in Bologna, particularly those reproducing Titian’s work, and how these affected Annibale’s ideas about composition and the representation of figures and landscape. It reconsiders Agostino’s role as an engraver of Venetian paintings in transmitting ideas about Venetian art to Annibale.