Report | Volume 2 Volume 2 Margaret Cunneen SC 30 May 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

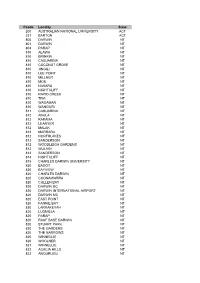

Pcode Locality State 200 AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL

Pcode Locality State 200 AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY ACT 221 BARTON ACT 800 DARWIN NT 801 DARWIN NT 804 PARAP NT 810 ALAWA NT 810 BRINKIN NT 810 CASUARINA NT 810 COCONUT GROVE NT 810 JINGILI NT 810 LEE POINT NT 810 MILLNER NT 810 MOIL NT 810 NAKARA NT 810 NIGHTCLIFF NT 810 RAPID CREEK NT 810 TIWI NT 810 WAGAMAN NT 810 WANGURI NT 811 CASUARINA NT 812 ANULA NT 812 KARAMA NT 812 LEANYER NT 812 MALAK NT 812 MARRARA NT 812 NORTHLAKES NT 812 SANDERSON NT 812 WOODLEIGH GARDENS NT 812 WULAGI NT 813 SANDERSON NT 814 NIGHTCLIFF NT 815 CHARLES DARWIN UNIVERSITY NT 820 BAGOT NT 820 BAYVIEW NT 820 CHARLES DARWIN NT 820 COONAWARRA NT 820 CULLEN BAY NT 820 DARWIN DC NT 820 DARWIN INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT NT 820 DARWIN MC NT 820 EAST POINT NT 820 FANNIE BAY NT 820 LARRAKEYAH NT 820 LUDMILLA NT 820 PARAP NT 820 RAAF BASE DARWIN NT 820 STUART PARK NT 820 THE GARDENS NT 820 THE NARROWS NT 820 WINNELLIE NT 820 WOOLNER NT 821 WINNELLIE NT 822 ACACIA HILLS NT 822 ANGURUGU NT 822 ANNIE RIVER NT 822 BATHURST ISLAND NT 822 BEES CREEK NT 822 BORDER STORE NT 822 COX PENINSULA NT 822 CROKER ISLAND NT 822 DALY RIVER NT 822 DARWIN MC NT 822 DELISSAVILLE NT 822 FLY CREEK NT 822 GALIWINKU NT 822 GOULBOURN ISLAND NT 822 GUNN POINT NT 822 HAYES CREEK NT 822 LAKE BENNETT NT 822 LAMBELLS LAGOON NT 822 LIVINGSTONE NT 822 MANINGRIDA NT 822 MCMINNS LAGOON NT 822 MIDDLE POINT NT 822 MILIKAPITI NT 822 MILINGIMBI NT 822 MILLWOOD NT 822 MINJILANG NT 822 NGUIU NT 822 OENPELLI NT 822 PALUMPA NT 822 POINT STEPHENS NT 822 PULARUMPI NT 822 RAMINGINING NT 822 SOUTHPORT NT 822 TORTILLA -

The University News, Vol. 6, No. 3, March 20, 1980

'f\.-~\r.,v-eo VOL 6 NO 3 20 MARCH 80 Newsletter for ( The University of Newcastle U /G PASS RATES a ""mber of ho"" per week that a REPRODU CTIVE M EDICIN E full-time student is advised to The Vice-Chancellor. Professor At its meeting on March 5, the spend on study. Members of staff . Don George, has announced the Senate considered the Report of will be advised to take reasonable appOintment of Dr. Jeffrey the Committee to Consider Under care to ensure that attendance at Robfnson of Oxford UniYersity to graduate Pass Rates. classes, set work and required the Foundation Chair of Reproduct- Senate recognised the com reading for each subject can be iye Medicine in the. Faculty of plexity of the problems. which accomplished within the appropriate Medicine in the University. are by no means confined to this fraction of the total number of Dr. Robinson. who 1s 37 years University alone. Senate was an hours recommended. of age. was educated at Queen's xious to treat the matter serious The Senate also supported the University. Belfast, where he ly. whilst keeping the issues in appointment of external examiners graduated in 1967 as· B.Sc. (Anat- proportion. It considered that for all Departments. An examin-- omy) with 1st Class Honours and positive action could be taken on ation result "terminating pass" in 1967 as M.B., B.A .• B.A.O. In 'several levels. In principle, was approved for introduction at 1970 he took up a Nufffeld Fellow- the Senate believes that the pro the discretion of Faculty and ship in the Nuffield Institute blems can only be solved at Departmental Boards. -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 73 Friday, 15 May 2009 Published Under Authority by Government Advertising

2233 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 73 Friday, 15 May 2009 Published under authority by Government Advertising LEGISLATION Online notification of the making of statutory instruments Week beginning 4 May 2009 THE following instruments were officially notified on the NSW legislation website (www.legislation.nsw.gov.au) on the dates indicated: Regulations and other statutory instruments Supreme Court Rules (Amendment No. 416) 2009 (2009-165) — published LW 8 May 2009 Uniform Civil Procedure Rules (Amendment No. 26) 2009 (2009-166) — published LW 8 May 2009 Environmental Planning Instruments Hornsby Shire Local Environmental Plan 1994 (Amendment No. 96) (2009-167) – published LW 8 May 2009 Lake Macquarie Local Environmental Plan 2004 (Amendment No. 34) (2009-168) – published LW 8 May 2009 Penrith Local Environmental Plan (Glenmore Park Stage 2) 2009 (2009-170) — published LW 8 May 2009 Penrith Local Environmental Plan No. 188 (Amendment No. 6) (2009-169) — published LW 8 May 2009 2234 LEGISLATION 15 May 2009 Acts of Parliament Assented To Legislative Assembly Office, Sydney 13 May 2009 IT is hereby notified, for general information, that Her Excellency the Governor has, in the name and on behalf of Her Majesty, this day assented to the undermentioned Acts passed by the Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council of New South Wales in Parliament assembled, viz.: Act No. 15 2009 – An Act to make miscellaneous amendments to various Acts administered by the Minister for Health; and for other purposes. [Health Legislation Amendment Bill] Act No. 16 2009 – An Act to amend the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) (New South Wales) Act 1987 to harmonise its provisions with those of the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 of the Commonwealth; and for other purposes. -

ASIC Gazette

Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No. UM4/11, Friday, 6 May 2011 Published by ASIC ASIC Gazette Contents Banking Act Unclaimed Money as at 31 December 2010 Specific disclaimer for Special Gazette relating to Banking Unclaimed Monies The information in this Gazette is provided by Authorised Deposit-taking Institutions to ASIC pursuant to the Banking Act (Commonwealth) 1959. The information is published by ASIC as supplied by the relevant Authorised Deposit-taking Institution and ASIC does not add to the information. ASIC does not verify or accept responsibility in respect of the accuracy, currency or completeness of the information, and, if there are any queries or enquiries, these should be made direct to the Authorised Deposit-taking Institution. RIGHTS OF REVIEW Persons affected by certain decisions made by ASIC under the Corporations Act 2001 and the other legislation administered by ASIC may have rights of review. ASIC has published Regulatory Guide 57 Notification of rights of review (RG57) and Information Sheet ASIC decisions – your rights (INFO 9) to assist you to determine whether you have a right of review. You can obtain a copy of these documents from the ASIC Digest, the ASIC website at www.asic.gov.au or from the Administrative Law Co-ordinator in the ASIC office with which you have been dealing. ISSN 1445-6060 (Online version) Available from www.asic.gov.au ISSN 1445-6079 (CD-ROM version) Email [email protected] © Commonwealth of Australia, 2010 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all rights are reserved. -

2018-2019 Annual Report

Annual 2018/19 Report newcastle.nsw.gov.au Acknowledgment Contents City of Newcastle acknowledges that we operate on Welcome the grounds of the traditional country of the Awabakal and Worimi peoples. Lord Mayor message 6 We recognise and respect their cultural heritage, beliefs CEO message 7 and continuing relationship with the land, and that they Year in review 8 are the proud survivors of more than two hundred years of dispossession. Our City CN reiterates its commitment to address disadvantages Newcastle at a glance 28 and attain justice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this community. Our people, our city 30 Our vision 32 Governing our city 35 Our organisation 51 Why we do an Annual Report 68 Our stakeholders 70 Our Performance 2018/19 highlights 74 Strategic directions Integrated and Accessible Transport 77 Protected Environment 87 Vibrant, Safe and Active Public Places 97 Inclusive Community 107 Liveable Built Environment 119 Smart and Innovative 129 Open and Collaborative Leadership 139 Financial performance 158 Sustainable Development Goal performance 170 Enquiries Our Statutory Reporting For information contact Our accountability 178 Corporate Strategist Appendix Phone 4974 2000 Legislative checklist 200 Published by Glossary 201 City of Newcastle PO Box 489, Newcastle NSW 2300 Phone 4974 2000 Fax 4974 2222 [email protected] newcastle.nsw.gov.au © 2019 City of Newcastle Welcome City of Newcastle City of 4 Bathers way walk, AnnualBar Beach Report 2018/19 5 A message from A message from our our Lord Mayor Chief Executive Officer As a United Nations city we are committed to infrastructure renewal with revitalisation projects to City of Newcastle (CN) had a record-setting A variety of projects to improve the city’s newly contributing towards the achievement of the United meet the higher community expectations that come 2018/19 for all the right reasons, not least because emerging CBD are included in the West End Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). -

Annual Report

ANZBCTG Annual Report Research for a world without breast cancer. Annual Report 1 April 2012 - 31 March 2013 1 April 2012 - 31 Mar ch 2013 The Australia and New Zealand Breast Cancer Trials Group is supported by its fundraising department the Breast Cancer Institute of Australia. Australia & New Zealand Breast Cancer Trials Group Email: [email protected] Web: www.anzbctg.org or scan the following QR code: Trials Coordination Department Australia & New Zealand Breast Cancer Trials Group PO Box 155 Hunter Region Mail Centre NSW 2310 Australia Ph: (+61) 2 4985 0136 Fax: (+61) 2 4985 0141 Business Administration Department Australia & New Zealand Breast Cancer Trials Group PO Box 283 The Junction NSW 2291 Australia Ph: (+61) 2 4925 5255 Fax: (+61) 2 4925 3068 Fundraising & Education Department Breast Cancer Institute of Australia PO Box 283 The Junction NSW 2291 Australia Ph: (+61) 2 4925 3022 Fax: (+61) 2 4925 3068 Email: [email protected] Web: www.bcia.org.au ANZ Breast Cancer Trials Group Limited ACN 051 369 496 ABN 64 051 369 496 ATO N0939 ©2013. This report cannot be reproduced without the permission of the ANZ Breast Cancer Trials Group Ltd. All rights reserved. Contents Contents 1 About Us 2 Chair’s Report 4 Chief Operating Officer’s Report 6 Research Report 8 Clinical Trials Open for Participant Entry 20 Clinical Trials Accrual Completed 30 Communication Report 36 Consumer Advisory Panel Report 38 Fundraising Report 40 Fundraising Results and Highlights 42 Governance 56 Contributors and Supporters 62 Financial Report 66 Publications 70 Glossary of Terms 72 ANZBCTG Annual Report 2012-2013 1 About Us Our Mission: To eradicate all suffering from breast cancer through the highest quality clinical trials research. -

Pubuc Immf

4^ INDEX TO THE NEWCASTLE MORNING HERALD AND MINERS' ADVOCATE 197b Compile(d by The Newcastle Morning Herald Library NEWCASTLE puBuc immf ^^^ APR 1977w4o<:iVfc , (i^ v>^^^<) Published by NEWCASTLK PUBLIC LIBRARY The Council of the City of Newcastle New South Wales, Australia 1977 N.M.H. INDEX 1976 ABATTOIRS ABORIGINES (O'td) Beef slaughtering halt at Himebush 3.1:21 "Demon" bust of artist sou^t 20.4:12 Men go back at abattoir (Taree) 9.2:10 "Embassy" looks to overaeas 21.4:3 Dispute threatens meat supply 28.2:3 Aborigines arrest "Not Justified 30.4:7 Strike at abattoir 2.3:8 Truganini rests 1.5:3 New strike at abattoir 5.3:5 Truganini at rest 3.5:13 Abattoir talks fail. 9.3:6 National policy likely on police, Aborigines Meatworkers' strike threatens auppliea 10,3:5 6.5:9 Abattoir strikers to meet 11.3:7 Judge saw Aborigines refused hotel service ||1,35M loan allocation does not cov6r planned 7,5:4 abattoir 11.3:7 Publican gets away from Moree 8.5:5 Meat workers back Monday 12,3:7 Ear defects high for Aborigines 11.5:7 |25M Abattoir for ferley approved 6,5:1 Women barred from trial to keep Aboriginal rites Abattoir, a |30M Taj Mahal, butchers 7.5:3 aocret (Adelaide) 12.5:3 Abattoir site "put to use" 11.5:7 Aborigine to face tribal law, 15.5:3 Regional abattoir supported 19,5:14 Aboriginal girl is master of crafts 17.5:6 MLA'S bid for abattoir site awitoh 22.5:5 Aborigine mine council urged 17.5:7 Abattoir cost likened to Opera Hjuse 29.5:9 Aborigine speared by tribal elder for death Abattoir delegates to meet 9,6:15 19.5:1 Killing at abattoirs reduced 22,6:3 Opinions conflict on tribal spearing 20.5:3 Abattoirs strike may end 23,6:7 Aboriginal art show in U.S. -

Indigenous and Minority Placenames

Indigenous and Minority Placenames Indigenous and Minority Placenames Australian and International Perspectives Edited by Ian D. Clark, Luise Hercus and Laura Kostanski Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Clark, Ian D., 1958- author. Title: Indigenous and minority placenames : Australian and international perspectives Ian D. Clark, Luise Hercus and Laura Kostanski. Series: Aboriginal history monograph; ISBN: 9781925021622 (paperback) 9781925021639 (ebook) Subjects: Names, Geographical--Aboriginal Australian. Names, Geographical--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hercus, Luise, author. Kostanski, Laura, author. Dewey Number: 919.4003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Nic Welbourn and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Notes on Contributors . .vii 1 . Introduction: Indigenous and Minority Placenames – Australian and International Perspectives . 1 Ian D. Clark, Luise Hercus, and Laura Kostanski 2 . Comitative placenames in central NSW . 11 David Nash 3. The diminutive suffix dool- in placenames of central north NSW 39 David Nash 4 . Placenames as a guide to language distribution in the Upper Hunter, and the landnám problem in Australian toponomastics . 57 Jim Wafer 5 . Illuminating the cave names of Gundungurra country . 83 Jim Smith 6 . Doing things with toponyms: the pragmatics of placenames in Western Arnhem Land . -

Calvary Mater Newcastle Review of Operations 2015-2016

Review of Operations 2015/2016 Continuing the Mission of the Sisters of the Little Company of Mary Contents Report from the Chief Executive Officer 6 Department Reports 8 Activity and Statistical Information 53 Year in Review 54 A Snapshot of our Year 57 Research and Teaching Reports 59 Financial Report 2015/2016 80 Acknowledgement of Land and Traditional Owners Calvary Mater Newcastle acknowledges the Traditional Custodians and Owners of the lands of the Awabakal Nation on which our service operates. We acknowledge that these Custodians have walked upon and cared for these lands for thousands of years. We acknowledge the continued deep spiritual attachment and relationship of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to this country and commit ourselves to the ongoing journey of Reconciliation. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are respectfully advised that this publication may contain the words, names, images and/or descriptions of people who have passed away. 2015/2016 Calvary Mater Newcastle Review of Operations | 1 The Spirit of Calvary Calvary Mater Newcastle is a service of the Calvary group that operates public and private hospitals, retirement communities, and community care services in four states and two territories in Australia. Our Mission identifies why we exist We strive to bring the healing ministry of Jesus to those who are sick, dying and in need through ‘being for others’: • In the Spirit of Mary standing by her Son on Calvary. • Through the provision of quality, responsive and compassionate health, community and aged care services based on Gospel values, and • In celebration of the rich heritage and story of the Sisters of the Little Company of Mary. -

Discount Tarps Freight Zones

Legend Discount Tarps Yes = we deliver for the quoted freight shown in the listing *Limited = some suburbs in this zone may be covered additional Freight Zones freight charges may apply *Quote Only = we may be able to obtain a special quote additional freight charges will apply * email us to confirm shipping before bidding Suburb Pcode State Service ADELAIDE LEAD 3465 VIC Yes ADELAIDE PARK 4703 QLD Yes AARONS PASS 2850 NSW Yes ADELAIDE RIVER 846 NT Quote Only ABBA RIVER 6280 WA Limited ADELONG 2729 NSW Yes ABBEY 6280 WA Limited ADJUNGBILLY 2727 NSW Yes ABBEYARD 3737 VIC Yes ADVANCETOWN 4211 QLD Yes ABBEYWOOD 4613 QLD Yes ADVENTURE BAY 7150 TAS Quote Only ABBOTSBURY 2176 NSW Yes AEROGLEN 4870 QLD Yes ABBOTSFORD 2046 NSW Yes AFTERLEE 2474 NSW Yes ABBOTSFORD 3067 VIC Yes AGERY 5558 SA Yes ABBOTSFORD 4670 QLD Yes AGNES 3962 VIC Yes ABBOTSHAM 7315 TAS Quote Only AGNES BANKS 2753 NSW Yes ABELS BAY 7112 TAS Quote Only AGNES WATER 4677 QLD Yes ABERCORN 4627 QLD Yes AHERRENGE 872 NT Quote Only ABERCROMBIE 2795 NSW Yes AILSA 3393 VIC Limited ABERCROMBIE RIVER 2795 NSW Yes AINSLIE 2602 ACT Yes ABERDARE 2325 NSW Yes AIRDMILLAN 4807 QLD Yes ABERDEEN 2336 NSW Yes AIRDS 2560 NSW Yes ABERDEEN 2359 NSW Yes AIRE VALLEY 3237 VIC Yes ABERDEEN 7310 TAS Quote Only AIREYS INLET 3231 VIC Yes ABERFELDIE 3040 VIC Yes AIRLIE BEACH 4802 QLD Yes ABERFELDY 3825 VIC Yes AIRLY 3851 VIC Yes ABERFOYLE 2350 NSW Yes AIRPORT WEST 3042 VIC Yes ABERFOYLE PARK 5159 SA Yes AIRVILLE 4807 QLD Yes ABERGLASSLYN 2320 NSW Yes AITKENVALE 4814 QLD Yes ABERGOWRIE 4850 QLD Yes AITKENVALE -

The University News, Vol. 9, No. 16, September 15-29, 1983

NEW'DEAN Sculpture Exhibition The Vlce-Olancellor, Professor D.W. George, has announced the appolnt... nt of Dr. John HamIl ton, M.S., B.S., FR~ (ClInada), FRCP "( London), as the next Dean ,of tledlclne at the Unlver- ~Ity. Dr. Hamilton will succeed Professor Geoffrey Kal ferman, who has been Dean since the death In November, 1981 of the Foundation Dean, 'frofessor David Maddison. Or. Hamilton, who Is 45 years of age, Is currently public Health Specialist of the World Bank, based In washington D.C .. with project responslbll I ty for East and Southern Africa and South Asia. Orlgln a Ily a graduate of the MI dd I e sex Hosp I ta I tied I ca I Schoo I , London, Dr. Hamilton Joined the Scu I ptures made by Second Year Arch Itecture students have been staff of the McMoster Un I ver mounted between the Auchmuty LI brary and the un Ion Ell II dl ng to make slty tied I cal School In Canada a delightful outdoor exhibition. The sculpture project Is part of )In 1969 and was closely assoc the students' VIsual Studies course work. The sculptures were mede Iated with the Innovations In In the Depar1ment of Architecture with the assistance of Depart ...dlcal education there which ...nta I Graftsman Jeff RI chards. were the subject of close exam Ination at the tl ... the New The group of 40 students Initially selected the area for the exhibition and then Individually developed their sculptures In castle OJrrlQJlum was being various materials, attempting at the same time to maintain the ,~eve loped. -

Indigenous and Minority Placenames: Australian

Indigenous and Minority Placenames Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), Acton, ANU, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. Indigenous and Minority Placenames Australian and International Perspectives Edited by Ian D. Clark, Luise Hercus and Laura Kostanski Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Clark, Ian D., 1958- author. Title: Indigenous and minority placenames : Australian and international perspectives Ian D. Clark, Luise Hercus and Laura Kostanski. Series: Aboriginal history monograph; ISBN: 9781925021622 (paperback) 9781925021639 (ebook) Subjects: Names, Geographical--Aboriginal Australian. Names, Geographical--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hercus, Luise, author. Kostanski, Laura, author. Dewey Number: 919.4003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.