Biennial Budgeting: Options, Issues, and Previous Congressional Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programme Book COLOPHON

tolkien society UNQUENDOR lustrum day saturday 19 june 2021 celebrating unquendor's 40th anniversary theme: númenor 1 programme book COLOPHON This programme book is offered to you by the Lustrum committee 2021. Bram Lagendijk and Jan Groen editors Bram Lagendijk design and lay out For the benefit of the many international participants, this programme book is in English. However, of the activities, only the lectures are all in English. The other activities will be in Dutch, occasionally interspersed with English. tolkien society unquendor E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.unquendor.nl Instagram: www.instagram.com/unquendor Facebook: www.facebook.com/groups/unquendor Twitter: www.twitter.com/unquendor Youtube: www.youtube.com/user/tolkiengenootschap Discord: www.discord.gg/u3wwqHt9RE June 2021 CONTENTS Getting started ... 4 A short history of Unquendor 5 Things you need to know 6 Númenor: The very short story 7 Programme and timetable 8 y Lectures 9 Denis Bridoux Tall ships and tall kings Númenor: From Literary Conception y to Geographical Representation 9 Renée Vink Three times three, The Uncharted Consequences of y the Downfall of Númenor 9 What brought they from Hedwig SlembrouckThe Lord of the Rings Has the history of the Fall of Númenor y been told in ?? 9 the foundered land José Maria Miranda y Law in Númenor 9 Paul Corfield Godfrey, Simon Crosby Buttle Over the flowing sea? WorkshopsThe Second Age: A Beginning and an End 910 y Seven stars and seven stones Nathalie Kuijpers y Drabbles 10 QuizJonne Steen Redeker 10 And one white tree. Caroline en Irene van Houten y Jan Groen Gandalf – The Two Towers y Poem in many languages 10 Languages of Númenor 10 Peter Crijns, Harm Schelhaas, Dirk Trappers y Dirk Flikweert IntroducingLive cooking: the presentersNúmenórean fish pie 1011 Festive toast and … 14 Participants 15 Númenórean fish pie 16 Númenóreaanse vispastei 17 GETTING STARTED… p deze Lustrumdag vieren we het 40-jarig Obestaan van Unquendor! Natuurlijk, we had- den een groot Lustrumfeest voor ogen, ons achtste. -

Before the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission

BEFORE THE WASHINGTON UTILITIES AND TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION In the Matter of Puget Sound Energy DOCKET UE-171087 2018-2019 Biennial Conservation Plan ____________________________________ In the Matter of Avista Corporation 2018- DOCKET UE-171091 2019 Biennial Conservation Plan ____________________________________ In the Matter of Pacific Power and Light Company 2018-2019 Biennial DOCKET UE-171092 Conservation Plan COMMISSION STAFF COMMENTS REGARDING ELECTRIC UTILITY CONSERVATION PLANS UNDER THE ENERGY INDEPENDENCE ACT, RCW 19.285 and WAC 480-109 (2018-2019 BIENNIAL CONSERVATION PLANS) December 1, 2017 Dockets UE-171087, UE-171091, UE-171092 Staff Comments on 2018-2019 Biennial Conservation Plans Page i Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Target Setting and Implementation Plans ....................................................................................... 4 NEEA........................................................................................................................................... 4 Decoupling Calculation .............................................................................................................. 6 Rebate Incentive Level ................................................................................................................ 7 Hard to Reach Markets ............................................................................................................... 7 Additional -

Second Biennial Report of the European Union Under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change

© iStockphoto/ liewy Second Biennial Report of the European Union under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change Climate Action The Second Biennial Report of the European Union represents a compilation of the following documents: COM(2015)642 - REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION - Second Biennial Report of the European Union under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (required under Article 18(1) of Regulation (EU) No 525/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2013 on a mechanism for monitoring and reporting greenhouse gas emissions and for repor- ting other information at national and Union level relevant to climate change and repealing Decision No 280/2004/EC and Decision 2/CP.17 of the Conference of Parties of the UNFCCC) Accompanying Staff Working Document: SWD(2015)282 - COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT - Accompanying the document Report from the Commission Second Biennial Report of the European Union Under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (required under Article 18(1) of Regulation (EU) No 525/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2013 on a mechanism for monitoring and reporting greenhouse gas emissions and for reporting other information at national and Union level relevant to climate change and repealing Decision No 280/2004/EC and Decision 2/CP.17 of the Conference of Parties of the UNFCCC) Table of Contents SECOND BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE EUROPEAN UNION UNDER THE UN FRAMEWORK CONVENTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE ..................................... I 1. GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSION INVENTORIES .................................................. 1 1.1. Summary information on GHG emission trends ............................................... 1 1.2. -

HG 2005 Sumer

V The HourglassV The Semi-Annual Newsletter of the 7th Infantry Division Association Summer 2005 V 7th Infantry Division Association 8048 Rose Terrace Comments from your Largo, FL 33777-3020 President http://www.7th-inf-div-assn.com In this issue... Our 20th Biennial Reunion is slated for September 15th-18th, 2005 at the 1. Comments from your President Marriott Airport, in Atlanta, Georgia. After 2. We Get Letters my visit there in October 2004 I noted 7. Looking Back Through the Hourglass that although the hotel is very nice, the 9. New Veterans ID Cards food is very costly. There was a lengthy 10. The Quartermaster’s Store wait for the luggage at the airport but the 12. Seekers Page 12. 7th IDA Web Site Marriott shuttle runs about every 15 13. A Personal Journey minutes during the daytime hours. 13. Treasurer’s Report 14. War on the Kwajalein Atoll For those who are driving in, please advise the parking attendants 15. Memoirs of a Solder you are with the 7th Reunion group, otherwise parking is very 16. Poems from a Military View expensive. And make sure to reserve your room well in advance 17. Returning Soldiers Need Listeners to get the best choice. 18. Introducing Our New Editor 18. For Your Information My continued bad health leaves me in constant pain, and it is 19. Infantry Soldiers in Iraq very difficult for me to be your President, Secretary, Roster 20. Departing Troops Need Support and Membership person all in one. I need all the help I can get 21. -

The History of Time and Leap Seconds

The History of Time and Leap seconds P. Kenneth Seidelmann Department of Astronomy University of Virginia Some slides thanks to Dennis D. McCarthy Time Scales • Apparent Solar Time • Mean Solar Time • Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) • Ephemeris Time (ET) • Universal Time (UT) • International Atomic Time (TAI) • Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) • Terrestrial Time (TT) • Barycentric Coordinate Time (TCB) • Geocentric Coordinate Time (TCG) • Barycentric Dynamical Time (TDB) Apparent Solar Time Could be local or at some special place like Greenwich But So… Length of the • We need a Sun apparent solar that behaves day varies during the year because Earth's orbit is inclined and is really an ellipse. Ptolemy (150 AD) knew this Mean Solar Time 360 330 300 270 240 210 Equation of Time 180 150 Day of the Year Day 120 90 60 30 0 -20 -15 -10 -5 0 5 10 15 20 Mean minus Apparent Solar Time - minutes Astronomical Timekeeping Catalogs of Positions of Celestial Objects Predict Time of an Event, e.g. transit Determine Clock Corrections Observations Observational Residuals from de Sitter Left Scale Moon Longitude; Right Scale Corrections to Time Universal Time (UT) • Elementary conceptual definition based on the diurnal motion of the Sun – Mean solar time reckoned from midnight on the Greenwich meridian • Traditional definition of the second used in astronomy – Mean solar second = 1/86 400 mean solar day • UT1 is measure of Earth's rotation Celestial Intermediate Pole angle – Defined • By observed sidereal time using conventional expression – GMST= f1(UT1) • -

Twenty-Second Biennial Report 59

Twenty-Second Biennial Report 59 DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MARSHALL T. HUNTTING, Supervisor BIENNIAL REPORT NO. 10 P ART I ADMINISTRATION The following report applies to the organization and activities of the Division of Mines and Geology, Department of Conservation, for the period July l , 1962 to June 30, 1964. INTRODUCTION The Division of Mines and Geology is a service agency; its function is to promote maximum utiliza tion of the State's mineral resources. Its only regulatory activities are those in administering the Oil and Gas Conserva tion Act. It acts as a clearing house of information on the geology and mineral resources of the State. Known mineral deposits are evaluated through field and office research, and through geologic mapping the basic information is provided that is needed in the search for new ore deposits. The Division collects statistics concerning the occurrence and production of minerals economically important in Washington; publishes bulletins on the geology, mineral resources, and mineral statistics of the State; maintains a collection of rock and mineral samples (at least 5,200 specimens) with special emphasis on those of economic importance or potential; maintains a library (ap proximately 13,000 volumes) of books, reports, records, and maps on geology, mineralogy, and mining, with special emphasis on material that pertains to Washington; and makes them available to the public for reference in the Division office. The Division also identifies samples of ores and minerals sent in by the public. The Division is building up a collection of oil well cores and cuttings that are extensively used by oil companies in exploring, both in Washington and as far as 50 miles offshore. -

History of the International Atomic Energy Agency: First Forty Years, by David Fischer

IAEA_History.qxd 10.01.2003 11:01 Uhr Seite 1 HISTORY OF THE INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC Also available: ENERGY International Atomic Energy Agency: Personal Reflections (18 ✕ 24 cm; 311 pp.) AGENCY The reflections are written by a group of distinguished scientists and diplomats who were involved in the establishment or The First Forty Years subsequent work of the IAEA. It represents a collection of by ‘essays’ which offer a complementary and personal view on some of the topics considered in the full history. David Fischer A fortieth anniversary publication ISBN 92–0–102397–9 IAEA_History.qxd 10.01.2003 11:01 Uhr Seite 2 The ‘temporary’ In 1979, the Austrian headquarters of Government and the IAEA in the City of Vienna the Grand Hotel, on completed construction the Ringstrasse in of the Vienna central Vienna. International Centre The Agency remained (VIC), next to the there for some Donaupark, which twenty years, until 1979. became the permanent home of the IAEA and other UN organizations. Austria generously made the buildings and facilities at the VIC available at the ‘peppercorn’ rent of one Austrian Schilling a year. IAEA_History.qxd 10.01.2003 11:01 Uhr Seite 2 The ‘temporary’ In 1979, the Austrian headquarters of Government and the IAEA in the City of Vienna the Grand Hotel, on completed construction the Ringstrasse in of the Vienna central Vienna. International Centre The Agency remained (VIC), next to the there for some Donaupark, which twenty years, until 1979. became the permanent home of the IAEA and other UN organizations. Austria generously made the buildings and facilities at the VIC available at the ‘peppercorn’ rent of one Austrian Schilling a year. -

Biennial Report of Activities and Programs July 1, 2016 to June 30, 2018

Biennial Report of Activities and Programs July 1, 2016 to June 30, 2018 Photo by Tom Patton, who retired as Research Chief this biennium after 39 years with the MBMG. Contact us: Butte 1300 W. Park Street Butte, MT 59701 Phone: 406-496-4180 Fax: 406-496-4451 Billings 1300 N. 27th Street Billings, MT 59101 Phone: 406-657-2938 This mosaic of the geologic map of Montana is made up of hundreds of images of MBMG staff , Fax: 406-657-2633 photos, and publications. 2019 is the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology. This report was created and printed by Publications staff of the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology. A department of Montana Technological University Biennial Report 2016-2018 COMMITTEES The Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology endeavors to provide sound scientifi c maps and reports for use by many segments of society. An important component of our activities is the decision process to determine topics and geographic areas of our research; advisory groups and steering committees are critical to that process. The MBMG gratefully acknowledges the many individuals and agencies who participate on these committees. Advisory Committees Ground Water Assessment Program and Ground Water State Map Advisory Committee Investigation Program Steering Committee Mr. Tim Bartos, USGS VOTING MEMBERS Dr. John Childs, Childs Geoscience Mr. Attila Folnagy , Department of Natural Resources Mr. Steven J. Czehura, Montana Resources Mr. Chris Boe, Department of Environmental Quality Mr. James W. Halvorson, MT Board of Oil and Gas Conservation Mr. Brett Heitshusen, Department of Agriculture Dr. -

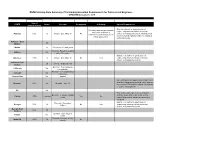

NSPE State-By-State Summary of Continuing Education Requirements for Professional Engineers - UPDATED January 21, 2015

NSPE State-by-State Summary of Continuing Education Requirements for Professional Engineers - UPDATED January 21, 2015 Year of STATE Hours Renewal Preapproval Self-study Special Requirement Implementation Must be relevant to the profession of Self-study and Internet courses: engineering and may include technical, must show evidence of Alabama 1991 15 Annual - December 31 No ethical, or managerial content. Management achievement and completion or courses must be sponsored by a recognized a final graded test. technical society. Alabama - Dual 20 PE/PLS Alaska 24 December 31 - odd years Triennial -Based on original Arizona No date of licensure Must be relevant to the profession of Arkansas 1998 15 Annual - December 31 No Yes engineering and may include technical, ethical, or managerial content. Arkansas Dual 20 Annual - September 30 PE/PLS Biennial - from assigned California No renewal date Biennial - from original date Colorado No of licensure Connecticut No Annual No less than 3 PDH and no more than 6 PDH shall be related to professional ethics, and no Delaware 2013 24 Biennial - June 30 more than 9 PDH shall be related to business or project mannagement DC No Four hours shall relate to areas of practice Biennial - February 28/Odd and four hours shall relate to rules of the Florida 2000 8 annual Yes No years board. No personal improvement courses accepted. Must be relevant to the profession of Biennial - December Georgia 1997 30 No Yes engineering and may include technical, 31/Even ethical, or managerial content. Georgia Dual 1997 30 PE/PLS Biennial - April 30/Even Hawaii No years Biennial - Last day of birth Idaho/PE 2009 30 No month Year of STATE Hours Renewal Preapproval Self-study Special Requirement Implementation Biennial-begin on day PDH units must come from two or more Idaho 1999 30 No Yes following birthdate activities listed on state board Web site. -

Climatology and Forcing of the Quasi-Biennial Oscillation in the MAECHAM5 Model

3882 JOURNAL OF CLIMATE—SPECIAL SECTION VOLUME 19 Climatology and Forcing of the Quasi-Biennial Oscillation in the MAECHAM5 Model M. A. GIORGETTA Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Hamburg, Germany E. MANZINI National Institute for Geophysics and Volcanology, Bologna, Italy E. ROECKNER AND M. ESCH Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Hamburg, Germany L. BENGTSSON Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Hamburg, Germany, and Environmental Systems Science Centre, University of Reading, Reading, United Kingdom (Manuscript received 23 January 2005, in final form 21 June 2005) ABSTRACT The quasi-biennial oscillation (QBO) in the equatorial zonal wind is an outstanding phenomenon of the atmosphere. The QBO is driven by a broad spectrum of waves excited in the tropical troposphere and modulates transport and mixing of chemical compounds in the whole middle atmosphere. Therefore, the simulation of the QBO in general circulation models and chemistry climate models is an important issue. Here, aspects of the climatology and forcing of a spontaneously occurring QBO in a middle-atmosphere model are evaluated, and its influence on the climate and variability of the tropical middle atmosphere is investigated. Westerly and easterly phases are considered separately, and 40-yr ECMWF Re-Analysis (ERA-40) data are used as a reference where appropriate. It is found that the simulated QBO is realistic in many details. Resolved large-scale waves are particularly important for the westerly phase, while pa- rameterized gravity wave drag is more important for the easterly phase. Advective zonal wind tendencies are important for asymmetries between westerly and easterly phases, as found for the suppression of the easterly phase downward propagation. -

Downloading Content Or Performing Intensive Calculations

Introduction: The Biennial Condition Joasia Krysa Lara Favaretto, Momentary Monument – The Stone, 2016. Installation view at Welsh Streets, Liverpool Biennial 2016. Photo: Mark McNulty. Liverpool, April 2017 This issue presents the proceedings from Liverpool Biennial’s 2016 conference The Biennial Condition: On Contemporaneity and the Episodic that took place in Liverpool in October 2016.[1] Drawing directly on the conference, it brings together the curatorial thinking behind the 2016 Biennial with ideas from Aarhus University’s research project The Contemporary Condition.[2] It aims to reflect on biennials both as the privileged site for the production of contemporaneity in art and exhibition making, and as episodic instances of contemporary art on a global scale. Liverpool Biennial 2016 was curated as a story in several episodes, with various fictional worlds sited in galleries, public spaces, disused buildings and online, taking the idea of simultaneity as opposed to linear narration as the grounding principle of the exhibition structure. Assembled by a Curatorial Faculty comprising Sally Tallant, Dominic Willsdon, Francesco Manacorda, Raimundas Malasauskas, Joasia Krysa, Rosie Cooper, Polly Brannan, Francesca Bertolotti-Bailey, Ying Tan, Sandeep Parmar and Steven Cairns, the exhibition took viewers on a series of expeditions through time and space, drawing on Liverpool’s past, present and future. These journeys took the form of six ‘episodes’ presented simultaneously across multiple sites in Liverpool: Ancient Greece, Chinatown, Children’s -

NC Insurance CE Licensee Hanbook

INSURANCE CONTINUING EDUCATION LICENSEE HANDBOOK Administrative Services Provided by Prometric Inc. January 2020 The information and requirements in this handbook are for resident agents and adjusters and certain non-resident adjusters with North Carolina CE requirements. Frequently Asked Questions 1. Who is required to take CE? Resident licensees who hold one or more of the following license types: Property, Casualty, Personal Lines, Life, Accident/Health/Sickness and Variable Life/Variable Annuity products and Adjusters (company/independent, public and self-employed) are required to take continuing education courses. Non-resident adjusters who qualified for licensure by passing the North Carolina exam, are also required to meet North Carolina CE requirements. (see Question #24) 2. How many CE credit hours are required each year? 24 credit hours of CE are required during each biennial compliance period (every two years). Twenty-four (24) credit hours are required regardless of how many licenses are held. 3. How do I determine my CE compliance date? An individual licensee’s compliance date is determined by the licensee’s birth month and birth year. CE is due by the last day of the birth month in either an odd or even year. If the birth year is odd, then CE is due by the last day of the birth month in the odd years. If the birth year is even, then CE is due by the last day of the birth month in the even years. 5. I am a new licensee. What are my CE requirements? If you are a new-licensee, you must earn 24 CE credits during each biennial compliance period (every 2 years).