Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dedication Donald Perrin De Sylva

Dedication The Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Mangroves as Fish Habitat are dedicated to the memory of University of Miami Professors Samuel C. Snedaker and Donald Perrin de Sylva. Samuel C. Snedaker Donald Perrin de Sylva (1938–2005) (1929–2004) Professor Samuel Curry Snedaker Our longtime collaborator and dear passed away on March 21, 2005 in friend, University of Miami Professor Yakima, Washington, after an eminent Donald P. de Sylva, passed away in career on the faculty of the University Brooksville, Florida on January 28, of Florida and the University of Miami. 2004. Over the course of his diverse A world authority on mangrove eco- and productive career, he worked systems, he authored numerous books closely with mangrove expert and and publications on topics as diverse colleague Professor Samuel Snedaker as tropical ecology, global climate on relationships between mangrove change, and wetlands and fish communities. Don pollutants made major scientific contributions in marine to this area of research close to home organisms in south and sedi- Florida ments. One and as far of his most afield as enduring Southeast contributions Asia. He to marine sci- was the ences was the world’s publication leading authority on one of the most in 1974 of ecologically important inhabitants of “The ecology coastal mangrove habitats—the great of mangroves” (coauthored with Ariel barracuda. His 1963 book Systematics Lugo), a paper that set the high stan- and Life History of the Great Barracuda dard by which contemporary mangrove continues to be an essential reference ecology continues to be measured. for those interested in the taxonomy, Sam’s studies laid the scientific bases biology, and ecology of this species. -

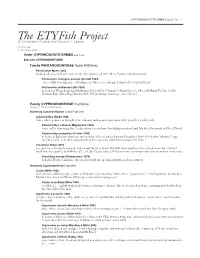

The Etyfish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J

CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3) · 1 The ETYFish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara COMMENTS: v. 3.0 - 13 Nov. 2020 Order CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3 of 4) Suborder CYPRINODONTOIDEI Family PANTANODONTIDAE Spine Killifishes Pantanodon Myers 1955 pan(tos), all; ano-, without; odon, tooth, referring to lack of teeth in P. podoxys (=stuhlmanni) Pantanodon madagascariensis (Arnoult 1963) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Madagascar, where it is endemic [extinct due to habitat loss] Pantanodon stuhlmanni (Ahl 1924) in honor of Franz Ludwig Stuhlmann (1863-1928), German Colonial Service, who, with Emin Pascha, led the German East Africa Expedition (1889-1892), during which type was collected Family CYPRINODONTIDAE Pupfishes 10 genera · 112 species/subspecies Subfamily Cubanichthyinae Island Pupfishes Cubanichthys Hubbs 1926 Cuba, where genus was thought to be endemic until generic placement of C. pengelleyi; ichthys, fish Cubanichthys cubensis (Eigenmann 1903) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Cuba, where it is endemic (including mainland and Isla de la Juventud, or Isle of Pines) Cubanichthys pengelleyi (Fowler 1939) in honor of Jamaican physician and medical officer Charles Edward Pengelley (1888-1966), who “obtained” type specimens and “sent interesting details of his experience with them as aquarium fishes” Yssolebias Huber 2012 yssos, javelin, referring to elongate and narrow dorsal and anal fins with sharp borders; lebias, Greek name for a kind of small fish, first applied to killifishes (“Les Lebias”) by Cuvier (1816) and now a -

George Brown Goode Collection, Circa 1814-1897 and Undated, with Related Materials to 1925

George Brown Goode Collection, circa 1814-1897 and undated, with related materials to 1925 Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Chronology....................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 4 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: AUTOGRAPH LETTERS, 1814-1895, AND UNDATED. ARRANGED ALPHABETICALLY................................................................................................... 6 Series 2: GENERAL CORRESPONDENCE, 1871-1896, AND UNDATED, with related materials to 1904. ARRANGED ALPHABETICALLY -

Fish Bulletin 161. California Marine Fish Landings for 1972 and Designated Common Names of Certain Marine Organisms of California

UC San Diego Fish Bulletin Title Fish Bulletin 161. California Marine Fish Landings For 1972 and Designated Common Names of Certain Marine Organisms of California Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/93g734v0 Authors Pinkas, Leo Gates, Doyle E Frey, Herbert W Publication Date 1974 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California STATE OF CALIFORNIA THE RESOURCES AGENCY OF CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME FISH BULLETIN 161 California Marine Fish Landings For 1972 and Designated Common Names of Certain Marine Organisms of California By Leo Pinkas Marine Resources Region and By Doyle E. Gates and Herbert W. Frey > Marine Resources Region 1974 1 Figure 1. Geographical areas used to summarize California Fisheries statistics. 2 3 1. CALIFORNIA MARINE FISH LANDINGS FOR 1972 LEO PINKAS Marine Resources Region 1.1. INTRODUCTION The protection, propagation, and wise utilization of California's living marine resources (established as common property by statute, Section 1600, Fish and Game Code) is dependent upon the welding of biological, environment- al, economic, and sociological factors. Fundamental to each of these factors, as well as the entire management pro- cess, are harvest records. The California Department of Fish and Game began gathering commercial fisheries land- ing data in 1916. Commercial fish catches were first published in 1929 for the years 1926 and 1927. This report, the 32nd in the landing series, is for the calendar year 1972. It summarizes commercial fishing activities in marine as well as fresh waters and includes the catches of the sportfishing partyboat fleet. Preliminary landing data are published annually in the circular series which also enumerates certain fishery products produced from the catch. -

The Surfperches)

UC San Diego Fish Bulletin Title Fish Bulletin No. 88. A Revision of the Family Embiotocidae (The Surfperches) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3qx7s3cn Author Tarp, Fred Harald Publication Date 1952-10-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California STATE OF CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME BUREAU OF MARINE FISHERIES FISH BULLETIN No. 88 A Revision of the Family Embiotocidae (The Surfperches) By FRED HARALD TARP October, 1952 1 2 3 4 1. INTRODUCTION* The viviparous surfperches (family Embiotocidae) are familiar to anglers and commercial fishermen alike, along the Pacific Coast of the United States. Until the present, 21 species have been recognized in the world. Two additional forms are herein described as new. Twenty species are found in California alone, although not all are restricted to that area. The family, because of its surf-loving nature, is characteristic of inshore areas, although by no means restricted to this niche. Two species are generally found in tidepools, while one, Zalembius rosaceus, occurs in fairly deep waters along the continental shelf. Because of their rather close relationships, the Embiotocidae have been a problem for the angler, the ecologist, the parasitologist, and others, to identify and even, occasionally, have proved to be difficult for the professional ichthy- ologist to determine. An attempt has been made in this revision, to remedy this situation by including full descrip- tions based on populations, rather than on individual specimens, and by including a key which, it is hoped, will prove adequate for juvenile specimens, as well as for adults. -

Inventory and Atlas of Corals and Coral Reefs, with Emphasis on Deep-Water Coral Reefs from the U

Inventory and Atlas of Corals and Coral Reefs, with Emphasis on Deep-Water Coral Reefs from the U. S. Caribbean EEZ Jorge R. García Sais SEDAR26-RD-02 FINAL REPORT Inventory and Atlas of Corals and Coral Reefs, with Emphasis on Deep-Water Coral Reefs from the U. S. Caribbean EEZ Submitted to the: Caribbean Fishery Management Council San Juan, Puerto Rico By: Dr. Jorge R. García Sais dba Reef Surveys P. O. Box 3015;Lajas, P. R. 00667 [email protected] December, 2005 i Table of Contents Page I. Executive Summary 1 II. Introduction 4 III. Study Objectives 7 IV. Methods 8 A. Recuperation of Historical Data 8 B. Atlas map of deep reefs of PR and the USVI 11 C. Field Study at Isla Desecheo, PR 12 1. Sessile-Benthic Communities 12 2. Fishes and Motile Megabenthic Invertebrates 13 3. Statistical Analyses 15 V. Results and Discussion 15 A. Literature Review 15 1. Historical Overview 15 2. Recent Investigations 22 B. Geographical Distribution and Physical Characteristics 36 of Deep Reef Systems of Puerto Rico and the U. S. Virgin Islands C. Taxonomic Characterization of Sessile-Benthic 49 Communities Associated With Deep Sea Habitats of Puerto Rico and the U. S. Virgin Islands 1. Benthic Algae 49 2. Sponges (Phylum Porifera) 53 3. Corals (Phylum Cnidaria: Scleractinia 57 and Antipatharia) 4. Gorgonians (Sub-Class Octocorallia 65 D. Taxonomic Characterization of Sessile-Benthic Communities 68 Associated with Deep Sea Habitats of Puerto Rico and the U. S. Virgin Islands 1. Echinoderms 68 2. Decapod Crustaceans 72 3. Mollusks 78 E. -

Anguilliformes, Saccopharyngiformes, and Notacanthiformes (Teleostei: Elopomorpha)

* Catalog of Type Specimens of Recent Fishes in the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 6: Anguilliformes, Saccopharyngiformes, and Notacanthiformes (Teleostei: Elopomorpha) DAVID G. SMITH I SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY • NUMBER 566 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs'submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

A List of the Publications of the United States National Museum (1875

A SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM. BULLETIN OF THE UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM. N^o. 51. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 19 2. ADVERTISEMENT. This work (Bulletin No, 51) is one of a series of papers intended to illustrate the collections belonging to or placed under the charge of the Smithsonian Institution and deposited in the United States National Museum. The publications of the National Museum consist of two series — the BuUetin and the Proceedings. The BuUetin., publication of which was commenced in 1875, is a series of elaborate papers issued separately and based for the most part upon collections in the National Museum. The}^ are monographic in scope and are devoted principalh' to the discussion of large zoolog- ical groups, bibliographies of eminent naturalists, reports of expedi- tions, etc. The bulletins, issued onl}^ as volumes with one exception, are of octavo size, although a quarto form, known as the Special Bul- letin, has been adopted in a few instances in which a larger page was deemed indispensable. The Proceedings (octavo), the first volume of which was issued in [878, are intended primarily as a medium of publication for newly acquired facts in biolog}", anthropology, and geology, descriptions of new forms of animals and plants, discussions of nomenclature, etc. A volume of about 1,000 pages is issued annuall}^ for distribution to libraries, while a limited edition of each paper in the volume is printed and distributed in pamphlet form in advance. In addition, there are printed each j^ear in the second volume of the Smithsonian Report (known as the Report of the National Museum) papers, chiefly of an ethnological character, describing collections in the National Museum. -

View/Download P

GOBIIFORMES (part 2) · 1 The ETYFish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara COMMENTS: v. 6.0 - 5 May 2020 Order GOBIIFORMES (part 2 of 7) Family OXUDERCIDAE Mudskipper Gobies (Acanthogobius through Oxyurichthys) Taxonomic note: includes taxa previously placed in the gobiid subfamilies Amblyopinae, Gobionellinae and Sicydiinae. Acanthogobius Gill 1859 acanthus, spine, allusion not explained, probably referring to 8-9 spines on first dorsal fin of A. flavimanus; gobius, goby Acanthogobius elongatus Fang 1942 referring to its more elongate body compared to congeners (then placed in Aboma) in China and Japan [A. elongata (Ni & Wu 1985) from Nanhui, Shanghai, China, is a junior primary homonym treated as valid by some authors but needs to be renamed] Acanthogobius flavimanus (Temminck & Schlegel 1845) flavus, yellow; manus, hand, referring to its yellow ventral fins Acanthogobius hasta (Temminck & Schlegel 1845) spear or dart, allusion not explained, perhaps referring to its very elongate, tapered body and lanceolate caudal fin Acanthogobius insularis Shibukawa & Taki 1996 of islands, referring to its only being known from island habitats Acanthogobius lactipes (Hilgendorf 1879) lacteus, milky; pes, foot, referring to milky white stripe in middle of fused ventral fins Acanthogobius luridus Ni & Wu 1985 pale yellow, allusion not explained, perhaps referring to body coloration and/or orange-brown tail Akihito Watson, Keith & Marquet 2007 in honor of Emperor Akihito of Japan (b. 1933), for his many contributions to goby systematics and phylogenetic research Akihito futuna Keith, Marquet & Watson 2008 named for the Pacific island of Futuna, where it appears to be endemic Akihito vanuatu Watson, Keith & Marquet 2007 named for the island nation of Vanuatu, only known area of occurrence Amblychaeturichthys Bleeker 1874 amblys, blunt, presumably referring to blunt head and snout of type species, A. -

List of Fish Found in the Freshwaters of Nova Scotia a Review of Common

CURATORIAL REPORT NUMBER 10 8 List of Fish found in the Freshwaters of Nova Scotia A review of Common Names and the taxonomy applied to these species with synonyms used in the literature relating to Nova Scotia, including Mi’kmaw names for fish by Andrew J Hebda CURATORIAL REPORTS The Reports of the Nova Scotia Museum make technical information on museum collections, programs, procedures, and research accessible to interested readers. This report contains the preliminary results of an on-going research program of the Museum. It may be cited in publications, but its manuscript status should be noted. _________________________________________________________________ © Crown Copyright 2019 Province of Nova Scotia Information in this report has been provided with the intent that it be readily available for research, personal and public non- commercial use and may be reproduced in part or in whole and by any means, without charge or further permission so long as credit is given to the Nova Scotia Museum. ISBN 978-1-55457-901-3 The correct citation for this publication is: Hebda, A.J., 2019, List of Fish found in the Freshwaters of Nova Scotia: A review of the taxonomy applied to these species with synonyms used in the literature relating to Nova Scotia including Mi’kmaw names for fish, Curatorial Report No. 108, Nova Scotia Museum, Halifax, 100 pages Cover image by Adam Cochrane – Lake Trout. Page | 2 Acknowledgements The author wishes to acknowledge the assistance of several individuals who have contributed to this manuscript in a number of ways. The author wishes to thank John Gilhen for reviewing versions of the manuscript, Maggie MacIntyre for insightful review of early drafts and Laura Bennett for suggestions and edits of the final document. -

Biographical Sketch of Spencer Fullerton Baird1

Biographical Sketch of Spencer Fullerton Baird Item Type article Authors Goode, George Brown Download date 25/09/2021 06:32:47 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/26460 Biographical Sketch of Spencer Fullerton Baird 1 University. He was, in 1878, awarded the silver medal of the Acclimatization Society of Melbourne; in 1879 the gold GEORGE BROWN GOODE medal of the Societe d'Acclimatation of France, and in 1880 the Erster Ehren preiz of the Internationale Fischerei I. Outline of His Public Career. tered upon his life work in connection Aussteilung at Berlin, the gift of the Em with that foundation-"the increase and peror of Germany. In 1875 he received Spencer Fullerton Baird was born in diffusion of useful knowledge among from the King of Norway and Sweden Reading, Pennsylvania, February 3, men."* His work as an officer of the the decoration of "Knight of the Royal 1823. In 1834 he was sent to a Quaker Institution will be discussed more fully Norwegian Order of St. Olaf." He was boarding-school kept by Dr. McGraw, below. It was constant and arduous, but one of the early members of the National at Port Deposit, Maryland, and the year did not prevent the publication of many Academy of Sciences, and ever since the following to the Reading Grammar original memoirs, among the most organization has been a member of its School. In 1836 he entered Dickinson elaborate of which are the "Catalogue council. In 1850 and 1851 he served as College, and was graduated at the age of North American Serpents" (1853); the permanent secretary of the American of seventeen. -

Spencer Baird and the Scientific Investigation of the Northwest Atlantic, 1871-1887

Spencer Baird and the Scientific Investigation of the Northwest Atlantic, 1871-1887 Dean C. Allard Between 1871 and 1887, Spencer Fullerton Baird organized and led a pioneering biological and physical investigation of the Northwest Atlantic oceanic region. Born in Pennsylvania in 1823, Baird was largely self-educated as a scientist in the era preceding the rise of major U.S. universities.1 Nevertheless, he became a major authority on the birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and fishes of North America. After 1850, as the Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC (in 1878 he became head of that organization), Baird used the numerous exploratory expeditions that the US government sent to the far reaches of the North American continent to gather enormous collections of scientific specimens and data. Those collections were a major impetus for the National Museum that Baird was developing within the Smithsonian, and were also the basis for a number of scientific publications on the biology of North America. By the early 1870s, in addition to his long-standing concern with terrestrial biology, Baird became increasingly interested in the oceanic environment. This new emphasis apparently grew out of the summers that Baird and his family spent at various locations along the Atlantic seaboard. In addition to offering a refuge from the oppressive heat of Washington, the sea shore offered ample opportunity for Baird to study oceanic life. He also was well aware that in this era Anton Dohrn, Charles Wyville Thomson, and other scientists throughout the world were turning their attention to the sea. All these investigators recognized that the study of the maritime environment was in its infancy.