The 1920S and 1930S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Former Pyree School Pyree Nsw

FORMER PYREE SCHOOL PYREE NSW CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN PREPARED FOR SHOALHAVEN CITY COUNCIL BRIDGE ROAD NOWRA NSW AUGUST 2001 REF: 0101: CMP TROPMAN & TROPMAN ARCHITECTS Architecture Conservation Landscape Interiors Urban Design Interpretation 55 LOWER FORT STREET SYDNEY NSW 2000 FAX (02) 9251 6109 PHONE (02) 9251 3250 Tropman Australia Pty Ltd ABN 71 088 542 885 ACN 088 542 885 Incorporated in New South Wales TROPMAN & TROPMAN ARCHITECTS Former Pyree School, Pyree Ref: 0101:CMP Conservation Management Plan August 2001 Contents 1.0 Executive Summary 1 2.0 Introduction 2 2.1 Brief 2 2.2 Study Area 3 2.3 Methodology 5 2.4 Limitations 5 2.5 Author Identification 6 3.0 Documentary Evidence 7 4.0 Physical Evidence 26 4.1 Identification of existing fabric 26 5.0 Analysis of Documentary and Physical Evidence 31 5.1 Analysis of Documentary Evidence 31 5.2 Analysis of Physical Evidence 31 6.0 Assessment of Cultural Significance 32 6.1 NSW Heritage Assessment Criteria 32 6.2 Statement of heritage significance 33 6.3 Nature of significance 34 6.4 Items of significance 34 6.5 Heritage Assessment Matrix 35 6.6 Grading of significance 35 6.7 Definition of curtilage 39 7.0 Constraints and Opportunities 40 7.1 Physical constraints and requirements arising from 40 the statement of significance 7.2 Procedural requirements (conservation methodology) 41 7.3 Constraints and requirements arising from 42 the physical and documentary evidence 7.4 Constraints and requirements arising from 42 the physical condition 7.5 External constraints 43 7.6 Opportunities -

Agenda of Shoalhaven Tourism Advisory Group

Meeting Agenda Shoalhaven Tourism Advisory Group Meeting Date: Monday, 10 May, 2021 Location: Council Chambers, City Administrative Centre, Bridge Road, Nowra Time: 5.00pm Please note: Council’s Code of Meeting Practice permits the electronic recording and broadcast of the proceedings of meetings of the Council which are open to the public. Your attendance at this meeting is taken as consent to the possibility that your image and/or voice may be recorded and broadcast to the public. Agenda 1. Apologies 2. Confirmation of Minutes • Shoalhaven Tourism Advisory Group - 24 March 2021 ............................................. 1 3. Presentations TA21.11 Rockclimbing - Rob Crow (Owner) - Climb Nowra A space in the agenda for Rob Crow to present on Climbing in the region as requested by STAG. 4. Reports TA21.12 Tourism Manager Update ............................................................................ 3 TA21.13 Election of Office Bearers............................................................................ 6 TA21.14 Visitor Services Update ............................................................................. 13 TA21.15 Destination Marketing ............................................................................... 17 TA21.16 Chair's Report ........................................................................................... 48 TA21.17 River Festival Update ................................................................................ 50 TA21.18 Event and Investment Report ................................................................... -

Discovering Bawley Point

Discovering Bawley Point A paradise on the NSW south coast 2 The Bawley Coast Contents Introduction page 3 Our history page 4 Wildlife page 6 Activities pages 8 Shopping page 14 Cafes and restaurants page 15 Vineyards and berry farms page 16 This e-book was written and published by Bill Powell, Bawley Bush Cottages, February 2011. Web: bawleybushcottages.com.au Email: [email protected] 101 Willinga Rd, Bawley Point, NSW 2539, Australia Tel: (61) 2 4457 1580 Bookings: (61) 2 4480 6754 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- sa/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Fran- cisco, California, 94105, USA. 3 Introduction A holiday on the Bawley Coast is still just like it was for our grandparents in their youth. Simple, sunny, lazy, memorable. Regenerating. This publication gives an over- view of the Bawley Coast area, its history and its present. There is also information about our coastal retreat, Bawley Bush Cottages. We hope this guide improves your ex- perience of this beautiful piece of Australian coast and hinterland. Here on the Bawley Coast geological history, evidence of aboriginal occupation and the more recent settler past are as easily visible as our beaches, lakes and cafes. Our coast remains relatively unspoiled by many of the trappings of town life. Recreation, sustain- ability and environmental protection are our high priorities. Landcare, dunecare and the protection of endangered species are examples of environ- mental activities important to our community. -

Agenda of Development & Environment Committee

Shoalhaven City Council Development & Environment Committee Meeting Date: Monday, 20 July, 2020 Location: Council Chambers, City Administrative Building, Bridge Road, Nowra Time: 5.00pm Membership (Quorum - 5) Clr Joanna Gash - Chairperson Clr Greg Watson All Councillors Chief Executive Officer or nominee Please note: The proceedings of this meeting (including presentations, deputations and debate) will be webcast and may be recorded and broadcast under the provisions of the Code of Meeting Practice. Your attendance at this meeting is taken as consent to the possibility that your image and/or voice may be recorded and broadcast to the public. Agenda 1. Apologies / Leave of Absence 2. Confirmation of Minutes • Development & Environment Committee - 2 June 2020 ............................................ 1 3. Declarations of Interest 4. Call Over of the Business Paper 5. Mayoral Minute 6. Deputations and Presentations 7. Notices of Motion / Questions on Notice Notices of Motion / Questions on Notice DE20.59 Notice of Motion - Call in DA20/1358 - Wilfords Lane MILTON - Lot 1 DP 1082590 .............................................................................................. 10 8. Reports Assets & Works DE20.60 Tomra Recycling Centre - Greenwell Point ............................................... 11 DE20.61 Road Closure - Unformed Road UPN102284 Separating Lot 28 & 14 DP 755927 - Conjola ................................................................................. 13 Development & Environment Committee – Monday 20 July 2020 Page -

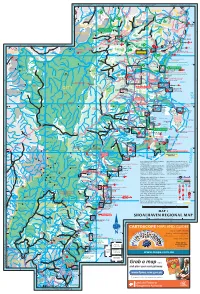

Shaolhaven Region

For adjoining map see Cartoscope's For adjoining map see Cartoscope's TO ALBION B Capital Country Tourist Map TO MOSS VALE 10km TO ROBERTSON 6km C Illawarra Region Tourist Map D PARK 5km TO SHELLHARBOUR 5km MOSS RD RD 150º30'E 150º20'E 150º40'E 150º50'E O Fitzroy Creek O RD R E Bundanoon Falls KIAMA B TD 15 Carrington Reservoir M AM Creek 79 in J Minnamurra Falls nam Dam urr Minnamurra a VALE Belmore River RIVER Falls Y Falls A 31km Creek Jamberoo MERYLA TD 8 BUDDEROO 9 W MERYLA Fitzroy MYRA H G Falls y I r n H o r o SF 907 a n Gerringong TD 9 34º40'S a g TRACK d n Falls n RD e u r NATIONAL B r Upper TO MARULAN Kiama River a Kangaroo B Valley BARRENCOUNCIL WINGECARRIBEE VALE Barrengarry PARK GROUNDS Saddleback TOURIST DRIVE Mt 7 8 Hampden Bridge: Mt 14 Built 1898, Saddleback 1 RD NR Lookout 1 oldest suspension BUDDEROO Foxground Mt Carrialoo bridge in Australia COUNCIL Mt CK Moollatoo Kangaroo Valley Creek Mt Pleasant Power Station Lookout Bendeela B Pondage For detail see ro WOODHILL ge Wattamolla RD Bendeela Map 10 rs MTN Werri Beach Bendeela Campground RD 3 LA Proposed RD OL RODWAY PRINCES Power TAM Upgrade Station Kangaroo WAT NR RD KAN 18 Gerringong Valley GA DR 13 RO BLACK For adjoining map see Cartoscope's 15 O ASH TD 7 A TO MARULAN 8km Capital Country Tourist Map Broughton NR 11 MT DEVILS CAOURA VALLEY GLEN NR RD Village Mt Skanzi 79 DAM Gerroa RD 9 For detail Berry Ck Marulan TALLOWA CAMBERWARRA RAILWAY 150º00'E 150º10'E Mt Phillips RANGE NR TD 7/8 see Map 15 Quarry FIRE Tallowa Dam Steep and very windy road, BEACH RD Black Head -

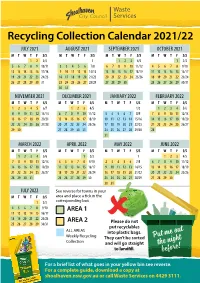

For a Brief List of What Goes in Your Yellow Bin See Reverse. for a Complete Guide, Download a Copy at Shoalhaven.Nsw.Gov.Au Or Call Waste Services on 4429 3111

For a brief list of what goes in your yellow bin see reverse. For a complete guide, download a copy at shoalhaven.nsw.gov.au or call Waste Services on 4429 3111. Calendar pick-up dates are colour coded to correspond with your area. AREA 1 Hyams Beach AREA 2 Mollymook Basin View Illaroo Back Forest Morton Bawley Point Jaspers Brush Bamarang Mundamia Beaumont Kings Point Bangalee Narrawallee Bellawongarah Kioloa Barrengarry North Nowra Berry Lake Tabourie Bendalong Nowra Bewong Meroo Meadow* Berrara Nowra Hill* Bomaderry Milton* Berringer Lake Numbaa Broughton Mollymook Beach* Bolong Pointer Mountain Budgong Myola Brundee* Pyree* Bundewallah Old Erowal Bay Cambewarra Sanctuary Point Burrill Lake Orient Point Comerong Island Shoalhaven Heads Callala Bay Parma Conjola South Nowra Callala Beach Termeil* Conjola Park St Georges Basin Croobyar* Tomerong* Coolangatta Sussex Inlet Culburra Beach Vincentia Cudmirrah Swanhaven Currarong Wandandian Cunjurong Point Tapitallee* Depot Beach Watersleigh Far Meadow* Terara Dolphin Point Wattamolla Fishermans Paradise Ulladulla Durras North Woodhill Jerrawangala West Nowra East Lynne Woollamia Kangaroo Valley Wollumboola Erowal Bay Worrigee* Lake Conjola Woodburn Falls Creek Worrowing Heights Little Forest Woodstock Greenwell Point Wrights Beach Longreach Yatte Yattah Huskisson Yerriyong Manyana * Please note: A small number of properties in these towns have their recycling collected on the alternate week indicated on this calendar schedule. Please go to shoalhaven.nsw.gov.au/my-area and search your address or call Waste Services on 4429 3111. What goes in your yellow bin Get the Guide! • Glass Bottles and Jars Download a copy at • Paper and Flattened Cardboard shoalhaven.nsw.gov.au • Milk and Juice Containers or call Waste Services • Rigid Plastic Containers (eg detergent, sauce, on 4429 3111. -

Planning Proposal for North Manyana

Planning Proposal for North Manyana Prepared for Kylor Pty Ltd October 2013 Planning Proposal for North Manyana Prepared for Kylor Pty Ltd | 31 October 2013 Ground Floor, Suite 01, 20 Chandos Street St Leonards, NSW, 2065 T +61 2 9493 9500 F +61 2 9493 9599 E [email protected] emgamm.com Planning proposal for North Manyana Final Report Version 3 Report J12075RP1 | Prepared for Kylor Pty Ltd | 31 October 2013 Prepared by Verity Blair Approved by Paul Mitchell Position Senior Environmental Planner Position Director Signature Signature Date 31 October 2013 Date 31 October 2013 This report has been prepared in accordance with the brief provided by the client and has relied upon the information collected at or under the times and conditions specified in the report. All findings, conclusions or recommendations contained in the report are based on the aforementioned circumstances. The report is for the use of the client and no responsibility will be taken for its use by other parties. The client may, at its discretion, use the report to inform regulators and the public. © Reproduction of this report for educational or other non‐commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from EMM provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this report for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without EMM’s prior written permission. Document Control Version Date Prepared by Reviewed by V1 1 November 2012 Verity Blair Paul Mitchell V2 12 February 2013 Verity Blair Paul Mitchell V3 31 October 2013 Verity Blair Paul -

Illawarra and South Coast Aborigines 1770-1900

University of Wollongong Research Online Senior Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Deputy Vice- Senior Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Deputy Vice- Chancellor (Education) - Papers Chancellor (Education) 1993 Illawarra and South Coast Aborigines 1770-1900 Michael K. Organ University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Organ, Michael K.: Illawarra and South Coast Aborigines 1770-1900 1993. https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers/118 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Illawarra and South Coast Aborigines 1770-1900 Abstract The following compilation of historical manuscript and published material relating to the Illawarra and South Coast Aborigines for the approximate period 1770 to 1900 aims to supplement that contained in the author's Illawarra and South Coast Aborigines 1770- 1850 (Wollongong University, 1990). The latter was compiled in a relatively short 18 month period between 1988 and 1989, and since then a great deal of new material has been discovered, with more undoubtedly yet to be unearthed of relevance to this study. As a result the present document contains material of a similar nature to that in the 1990 work, with an added emphasis on items from the period 1850 to 1900. Also included are bibliographic references which bring up to date those contained in the previous work. All told, some 1000 pages of primary sources and references to published works are now available on the Illawarra and South Coast Aborigines for the approximate period 1770 to 1900, though an attempt has been made to include items from this century which outline some of the history of the central Illawarra and Shoalhaven Aboriginal communities. -

South Coast T

SOUTH COAST T S d Ro CAMBEWARRA oa A wa Dam ad R Tallo RANGE N R Berry B KIAMA r O A e ive g ach R C Y a R A rs o d ad ke H d BUNGONIA d W o a LAKE a H L ro T o o G a C N P R I n R YARRUNGA t U d a ris H e o ou O R T a S r E C S EN RIVER C d a ALHAV RIN o a r SHO P o r n M o la e w n R o o S J g d SHO s H A k LHA a a VE s t o N M t o O a a o RIV in r L E Ro r A R a d e L R e BUGONG V G Th H a o le a A N P Bu d V g on R E g o a BUNGONIA N R d SEVEN MILE I o n a Il R d la v r BEACH N P d S C A o e I o a V r R B o a E o Shoalhaven o lo R r R a VEN RIVE n y ALHA R g MORTON d SHO Heads d R r S C A o R Bomaderry ad o o F a d Comerong I n sl Nowra a e e n l l d n a a R L o O ad B y ur d rie R Yalwa ad n r oa l Ro d A d a o y COMERONG KIAMA d R n G i ISLAND N R s r J s ee GOULBURN o nw tr e a ll P lb o in MORTON A WORRIGEE t R N P N R oad CURLEYS BAY R COLYMEA U E T V S C A B R RI Culburra oad EN AV KH d ROO oa CC SALTWATER rra R GOULBURN o Culbu o SWAMP N R WOLLUMBOOLA n R P e LAKE MULWAREE E a CURRAMBENE r m V m I a d Roa NOWRA i S F a R a d o R S F N JERVIS R E d o o BAY N P ng R a o V o Forest rar oa F d r d A w a Roa Cu id ll d H a s L r A B R PARMA o O a H CREEK d S J e N R r v is B a BEES y Wool NEST N R lamia TOMERONG R R o S F o a a d d Turpe R ntine oad Currarong WOOLLAMIA EN N R D R N Huskisson IC a K JERRAWANGALA d v a a R Ro l L I Y V N P Tomerong t i E SHOALHAVEN A s g R re h W t Br o C h H F aidwo Pine o JERVIS o od R l u o CITY G le ad I s g BAY e H e R S R ES o o H C a N ad I d O R P N A a L v H a A l VE R T ol R N RIVE he o -

Agenda of Extra Ordinary Meeting

Shoalhaven City Council Extra Ordinary Meeting Meeting Date: Tuesday, 12 May, 2020 Location: Council Chambers, City Administrative Building, Bridge Road, Nowra Time: At the conclusion of Strategy & Assets Committee Membership (Quorum - 7) All Councillors Please note: The proceedings of this meeting (including presentations, deputations and debate) will be webcast and may be recorded and broadcast under the provisions of the Code of Meeting Practice. Your attendance at this meeting is taken as consent to the possibility that your image and/or voice may be recorded and broadcast to the public. Agenda 1. Apologies / Leave of Absence 2. Declarations of Interest 3. Notices of Motion / Questions on Notice Notices of Motion / Questions on Notice CL20.104 Rescission Motion - CL20.102 Independent Legal Advice - Development Application - Lake View Drive Burrill Lake - Lot A DP21307 ..................................................................................................... 1 CL20.105 Notice of Motion - CL20.102 Independent Legal Advice - Development Application - Lake View Drive Burrill Lake - Lot A DP21307 ..................................................................................................... 9 4. Reports Planning Environment & Development CL20.106 NSW Coast & Estuary Grants - Bushfire Affected Waterways ................... 10 CL20.107 Proposed Subdivision of Land, Approved by NSW State Government - Manyana ................................................................................................. 18 Extra Ordinary -

Shallow Water Fish Communities of New South Wales South Coast Estuaries

FRDC Project 97/204: Shallow Water Fish Communities of New South Wales South Coast Estuaries R.J. West and M.V. Jones University of Wollongong Ocean and Coastal Research Centre Report Series Nos. 2001/1 January 2001 ISBN: 0 86418 739 4 FRDC Project 97/204 HISTORICAL NOTE Extracts from H.C. Dannevig (1906): “Correlation between our Home Fisheries and the Salt Water Lakes on the South Coast” “When visiting the Lakes district on the South Coast some little time ago, in company with the Hon. J.H. Want, a member of the Board, I had an opportunity of inspecting the principal nurseries from which our fish mainly migrate, and we also got a fair insight into the manner in which these waters are being worked. There are over forty salt-water lakes from St. Georges Basin to the border, with an area each of 30 acres or more, the total expanse being about 32,000 acres. Some of these waters are constantly open to the sea, others occasionally closed, while a few are only connected to the sea for a few weeks at a time, and then only at long intervals. It follows that the first-mentioned only are available to their full extent as natural nurseries, and the others with a closing entrance are more or less handicapped." Shallow water fishing method. Citation: West, R.J. and Jones, M.V. 2001. FRDC 97/204 Final Report: Shallow water fish communities of New South Wales south coast estuaries. Report Series Nos. 2001/1. Ocean and Coastal Research Centre, University of Wollongong, Australia. -

Dog Off-Leash Guide

Dog Off-Leash Guide Dogs in the Shoalhaven are required to be “on leash” at all times EXCEPT when in an “off leash area” Information accurate 01.08.2016 A Contents 4 Off-Leash areas 5 Dog prohibited areas 6-7 Shorebird Nesting Sites 8 Off-Leash Maps: 8 Shoalhaven Heads 9 Berry 10 Bomaderry 11 Nowra Showground 12 Worrigee 13 Culburra 14 Currarong 15 Callala Beach 16 Huskisson 17 Vincentia 18 Sanctuary Point Key to Off-leash Maps 19 Basin View 20 Swan Lake 21 Berrara 24 Hour off-leash exercise area 22 Bendalong 23 Lake Conjola 24 Milton Off-leash exercise area 25 Narrawallee restricted times 26 Mollymook 27 Mollymook/Ulladulla 28 Lake Tabourie Dogs Prohibited 29 Bawley Point 30 Useful Contacts 3 Off-Leash Areas Shoalhaven City Council promotes the benefits of pets and encourages responsible pet ownership through the provision of harmonious and equitable access to parks and open space for dogs and their owners. This guide provides information for pet owners on the location and use requirements of Off-Leash areas in the Shoalhaven Local Government Area. Dogs are required to be “on leash” at all times EXCEPT when in an Off-Leash Area. Dogs are only permitted to be “off-leash” in designated Council managed areas and must be under the control of a competent person at all times. Pet owners also need to be aware of the following: • Restricted breed dogs; dogs declared dangerous or menacing; or nuisance dogs are not permitted in off-leash areas; • Person in charge of the dog must immediately remove the dog’s faeces and properly dispose of them; • A dog must have a collar around its neck and there must be attached to the collar a name tag that shows the name of the dog and the address or telephone number of the owner of the dog; • All off-leash areas are regularly patrolled and all regulations enforced On the spot penalties apply for non-compliance Scan the QR code Information in this document is accurate at the time of printing below with your however may subsequently be updated.