Marco António Couto Sousa Star Wars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THX Room EQ Manual

Home THX Equalization Manual Rev. 1.5 Home THX Audio System Room Equalization Manual Rev. 1.5 This document is Copyright 1995 by Lucasfilm Ltd THX and Home THX are Registered Trademarks of Lucasfilm Ltd Dolby Stereo, Dolby Pro Logic, and Dolby AC-3 are trademarks of Dolby Laboratories Licensing Corporation 1 Home THX Equalization Manual Rev. 1.5 Table of Contents Introduction and Background: Why Room Equalization? ..................................... 3 Test Equipment Requirements ........................................................................... 4-5 The Home THX Equalizer ....................................................................................... 5 Equalization Procedures ................................................................................... 5-22 Section 1: EQ Procedure Using the THX R-2 Audio Analyzer ............................ 6-13 1.1 - 1.3 Test Equipment Set-Up ................................................................... 6-9 1.4 - 1.7 LCR Equalization ......................................................................... 10-11 1.8 - 1.10 Subwoofer Equalization ............................................................... 11-13 1.11 Listening Tests ................................................................................. 13 Section 2: EQ Procedure Using a Conventional RTA ...................................... 14-21 2.1 - 2.3 Test Equipment Set-Up ................................................................ 14-17 2.4 - 2.6 LCR Equalization ........................................................................ -

Digital Dialectics: the Paradox of Cinema in a Studio Without Walls', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television , Vol

Scott McQuire, ‘Digital dialectics: the paradox of cinema in a studio without walls', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television , vol. 19, no. 3 (1999), pp. 379 – 397. This is an electronic, pre-publication version of an article published in Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television is available online at http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=g713423963~db=all. Digital dialectics: the paradox of cinema in a studio without walls Scott McQuire There’s a scene in Forrest Gump (Robert Zemeckis, Paramount Pictures; USA, 1994) which encapsulates the novel potential of the digital threshold. The scene itself is nothing spectacular. It involves neither exploding spaceships, marauding dinosaurs, nor even the apocalyptic destruction of a postmodern cityscape. Rather, it depends entirely on what has been made invisible within the image. The scene, in which actor Gary Sinise is shown in hospital after having his legs blown off in battle, is noteworthy partly because of the way that director Robert Zemeckis handles it. Sinise has been clearly established as a full-bodied character in earlier scenes. When we first see him in hospital, he is seated on a bed with the stumps of his legs resting at its edge. The assumption made by most spectators, whether consciously or unconsciously, is that the shot is tricked up; that Sinise’s legs are hidden beneath the bed, concealed by a hole cut through the mattress. This would follow a long line of film practice in faking amputations, inaugurated by the famous stop-motion beheading in the Edison Company’s Death of Mary Queen of Scots (aka The Execution of Mary Stuart, Thomas A. -

Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB

Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB By Matthew Holtmeier Considering at least one “Star Wars” film has been released every decade since the 1970’s, this epic science fic- tion franchise likely jumps to mind upon hearing the name George Lucas. Avid filmgoers might think, instead, ‘Industrial Light and Magic,’ which has contributed to the special effects of over 275 feature films since it was founded by Lucas in 1975. Either way, Lucas’s penchant for the creation of fantastic worlds has radi- cally shaped the cinematic landscape of the past 40 years, particularly where big Dan Natchsheim as a character known simply as 1138 attempts budget films are concerned. Like many to escape a dystopian future society. Courtesy Library of filmmakers since the growth of film schools Congress Collection. in the 60’s, he started with a student film, however: “Electronic Labyrinth: THX1138 The Yardbirds, “I know. I know.” As the Gregorian 4EB” (1967). “Electronic Labyrinth” provides a strik- chant of The Yardbirds track begins, the camera ingly different vision of what the cinematic medium is tracks across an extreme close up of electronics capable of, particularly when compared to the mod- equipment, revealing the technocracy of the future. ern fairytales of the “Star Wars” films. It too has a The rest of the film will oscillate between the ‘operators’ science fictional setting, but one without heroes or of this technocracy, and THX 1138’s attempted escape princesses, and instead delves into the dystopian from the smooth, featureless white walls of a com- potential of technology itself. Giving vision to a world pound, presumably a world without desire. -

Ted Costas Press Release

TED COSTAS, FOUNDER AND PARTNER, SGI QC, TO RECEIVE INTER-SOCIETY’S KEN MASON AWARD Recognizes Contributions to Overall Motion Picture Experience In his current role as Founder/Partner at SGI QC, Ted oversees Domestic and International QC for several of the top studios. SGI has worked on major releases such as Transformers, The Avengers, and recently, Star Wars: The Force Awakens. SGI also helps on innovative engineering projects like the recent 35mm film release of InterStellar, and the 70mm film release of Hateful Eight, with installs and alignments. Ted was the only two-term President in the history of the Inter-Society, serving from 2004 to 2007. While President, Ted successfully worked to increase movie studio participation in the Inter-Society. Ted started the ISEC (Inter-Society Environmental Committee), which instituted both the Film Trailer Recycling Program and 3D Glasses recycling at a time when the 3D glasses were called “disposable.” Yet the most significant committee Ted started while President of the Inter-Society was the ISDCF (Inter-Society Digital Cinema Forum). No other committee or group has done more to “tame the Wild West of Digital Cinema” than the ISDCF and it’s seven years of successful monthly meetings. In 2007, Ted was named on the Sci-Tech Academy Award for the Cyan Dye Track Committee. Ted started his career at Lucasfilm, THX, where he spent fifteen years with the Theatre Alignment Program (TAP). At TAP, Ted started the Academy Award winning TASA Program (Trailer Audio Standards Association), to help limit volume levels in trailers domestically. Ted also oversaw the very first four Digital Cinema installations ever, for Star Wars Episode 1, in Los Angeles and New York. -

George Lucas and the Impact Star Wars Had on Modern Society

George Lucas And The Impact Star Wars Had On Modern Society. By: Rahmon Garcia George Lucas was a very famous director, and made many different films in his time as a director, but his most famous film he ever produced was Star Wars. The effect Star Wars had on modern society was pretty incredible; the way he could create an amazing story from a very abstract idea; If you walked up to any person and asked them if they knew the movie series Star Wars, their answer would definitely be yes. His movies changed our modern society and the way we look at aspects of life. George Walton Lucas Jr. was born May 14 1944, in Modesto, California. In his youth he attended the Southern California University for film. He was the Screenwriter and director of his school project and first major film, THX 1138 4EB, which was his first step on the path to becoming a great director. Although George Lucas was mostly known for being the director of movies such as ‘Star Wars’ and ‘Indiana Jones’, he also made many other films, such as ‘Twice Upon A Time’, ‘The Land Before Time’, ‘Willow’, ‘Strange Magic’, ect. Even though we now think of Star Wars as a great movie series, when it was in the making it was very hard to picture it would turn into such an incredible saga. Ever since George Lucas was in High School, he was obsessed with Car Racing, and would often try to repair or create a new engine for his car, until one day when he was racing he got into a really bad accident and was nearly killed, if it wasn't for his seat which ejected him after his seat belt broke. -

May the Fourth Awards Mercs Council

Mandalorian Mercs ISSUE 2 MERCS COUNCIL RESHUFFLE We introduce you to your new Council members. BUILDING A CLAN Dana Black’s mission to form a Dutch Clan. REGIONAL LOGOS Why Euro RC, Niabi, re-introduced an old tradition. MAY THE FOURTH AWARDS Mercs CAO discusses what’s up for grabs! PLANNING FOR The Mandalorian Mercs is a worldwide Star Wars costuming organization comprised of and operated by Star Wars fans and volunteers. It is the elite Mandalorian cos- tuming organization. Star Wars, its characters, costumes, and all associated items are the intellectual property of Lucasfilm. ©2013 Lucasfilm Ltd. & ™ All rights reserved. Used under authorization. welcome Greetings Mando Mercs members, friends, and fans, It seems like yesterday we were putting the finishing touches to issue #1, and now we’re releasing issue #2. We’ve had many developments in the Mercs and Star Wars since last issue; Episode VII director announce- ment, ‘3D Episodes on hold’ announcement, Membership Tiers, Verd’ika Corps kids club, Celebration Europe...the list could go on. 6 years ago this March, a small website and forum was launched to bring existing Mandalorian costumers into an organized and represent- ed group among the Star Wars community. From that small handful of people, Mandalorian Mercs has become home to thousands of mem- bers and fans around the world. My goal is to ensure that your Mercs family is here for your benefit, and that our home is a fixture in the Star Wars Universe. With your help, and the tireless help of others...we’ve been able to accomplish that goal thus far. -

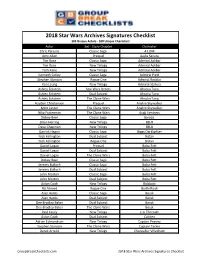

2018 Star Wars Archives Signatures Checklist

2018 Star Wars Archives Signatures Checklist 103 Unique Actors - 108 Unique Characters Actor Set - Story Chapter Character Chris Parsons Classic Saga 4-LOM Amy Allen Prequel Aayla Secura Tim Rose Classic Saga Admiral Ackbar Tim Rose New Trilogy Admiral Ackbar Tom Kane New Trilogy Admiral Ackbar Kenneth Colley Classic Saga Admiral Piett Stephen Stanton Rogue One Admiral Raddus Ken Leung New Trilogy Admiral Statura Ashley Eckstein Star Wars Rebels Ahsoka Tano Ashley Eckstein Dual Subject Ahsoka Tano Ashley Eckstein The Clone Wars Ahsoka Tano Hayden Christensen Prequel Anakin Skywalker Matt Lanter The Clone Wars Anakin Skywalker Nika Futterman The Clone Wars Asajj Ventress Dickey Beer Classic Saga Barada Brian Herring New Trilogy BB-8 Dave Chapman New Trilogy BB-8 Garrick Hagon Classic Saga Biggs Darklighter Nick Kellington Dual Subject Bistan Nick Kellington Rogue One Bistan Daniel Logan Prequel Boba Fett Daniel Logan Dual Subject Boba Fett Daniel Logan The Clone Wars Boba Fett Dickey Beer Classic Saga Boba Fett Jeremy Bulloch Classic Saga Boba Fett Jeremy Bulloch Dual Subject Boba Fett John Morton Classic Saga Boba Fett John Morton Dual Subject Boba Fett Aidan Cook New Trilogy Bobbajo Riz Ahmed Rogue One Bodhi Rook Alan Harris Classic Saga Bossk Alan Harris Dual Subject Bossk Dee Bradley Baker Dual Subject Bossk Dee Bradley Baker The Clone Wars Bossk Paul Kasey New Trilogy C'ai Threnalli Aidan Cook Dual Subject Caitken Adrian Edmondson New Trilogy Captain Peevey Stephen Stanton The Clone Wars Captain Tarkin Derek Arnold New Trilogy Chancellor -

A Nomadology of Inamoramento De Orlando and Star Wars

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-19-2018 2:00 PM Romance, Politics and Minor Art: A Nomadology of Inamoramento de Orlando and Star Wars Andrea Privitera The University of Western Ontario / Università degli studi di Padova Supervisor Boulter, Jonathan The University of Western Ontario Joint Supervisor Baldassarri, Guido University of Padova Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Andrea Privitera 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Italian Literature Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Privitera, Andrea, "Romance, Politics and Minor Art: A Nomadology of Inamoramento de Orlando and Star Wars" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5921. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5921 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstracts English While existing theories of romance (in particular, those formulated by Northrop Frye and Fredric Jameson) accurately characterize this literary mode as a highly politicized example of art, this thesis contends that the political nature of romance is broader and more complex than discussed so far. In order to offer a new and comprehensive political theory of romance, this work proposes a comparison between two historically and culturally diverse examples of romance, that is Matteo Maria Boiardo’s chivalric poem Inamoramento de Orlando and George Lucas’ space opera film Star Wars. -

CNN.Com Search

International Edition | MEMBER SERVICES The Web CNN.com Search Home Page World U.S. Weather Business The Lucas world, pre-'Star Wars' Sports Enter Keywords Politics A return to 'THX 1138' Enter City ALL Law Monday, September 13, 2004 Posted: 10:28 AM EDT (1428 GMT) Technology Science & Space SAN RAFAEL, California (AP) -- In Health his most soothing voice, George Entertainment Lucas has these important Travel messages to share: Work hard. Education Prevent accidents. Increase Special Reports production. Buy more. And most important, be happy. Those mantras come from 1971's "THX 1138," Lucas' comparatively unknown first film, which he reintroduced to audiences with a limited theatrical release Friday, to "THX 1138" was based on a student film be followed by its DVD debut Tuesday. George Lucas made at USC. SERVICES Video In a way, Lucas views this as the true E-mail Newsletters premiere of "THX 1138," a dark sci-fi satire Refinance Rates Just Got Lower Your E-mail Alerts starring Robert Duvall as the title Lock in the lowest rates of the character, struggling to escape a summer. Get up to 4 free refinance CNNtoGO dehumanized society whose inhabitants quotes. Contact Us are mere numbers to a government that www.lowermybills.com SEARCH preaches boundless consumerism and Home Equity Loans-4.25% APR Web CNN.com keeps the population happy through mandatory sedatives. Receive up to 4 free loan quotes from trusted lenders and get the cash you... "It's almost like it's a new movie, because a www.lowermybills.com Search lot of people don't know about it," Lucas told The Associated Press over lunch at his LendingTree.com - Official Site 2,600-acre Skywalker Ranch. -

"It's Aimed at Kids - the Kid in Everybody": George Lucas, Star Wars and Children's Entertainment by Peter Krämer, University of East Anglia, UK

"It's aimed at kids - the kid in everybody": George Lucas, Star Wars and Children's Entertainment By Peter Krämer, University of East Anglia, UK When Star Wars was released in May 1977, Time magazine hailed it as "The Year's Best Movie" and characterised the special quality of the film with the statement: "It's aimed at kids - the kid in everybody" (Anon., 1977). Many film scholars, highly critical of the aesthetic and ideological preoccupations of Star Wars and of contemporary Hollywood cinema in general, have elaborated on the second part in Time magazine's formula. They have argued that Star Wars is indeed aimed at "the kid in everybody", that is it invites adult spectators to regress to an earlier phase in their social and psychic development and to indulge in infantile fantasies of omnipotence and oedipal strife as well as nostalgically returning to an earlier period in history (the 1950s) when they were kids and the world around them could be imagined as a better place. For these scholars, much of post-1977 Hollywood cinema is characterised by such infantilisation, regression and nostalgia (see, for example, Wood, 1985). I will return to this ideological critique at the end of this essay. For now, however, I want to address a different set of questions about production and marketing strategies as well as actual audiences: What about the first part of Time magazine's formula? Was Star Wars aimed at children? If it was, how did it try to appeal to them, and did it succeed? I am going to address these questions first of all by looking forward from 1977 to the status Star Wars has achieved in the popular culture of the late 1990s. -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

"Design of the THX Deep Note" — Excerpt from Artful Design

"Design of the THX Deep Note" excerpt (pp. 176-181) from Artful Design, Chapter 4 "Programability and Sound Design" ARTFUL DESIGNTECHNOLOGY IN SEARCH OF THE SUBLIME A MusiComic Manifesto! 人 GE WANG https://artful.design/ © 2018 by Ge Wang. All rights reserved. the "ORDER + resolution" THX We can i%ustrate the program 3 (and a big CHORD!) graphica$y -- 30 lines To i!ustrate sound synthesis by way of parametric D!P represent the frequencies The target frequencies stack evolution, we are going to recreate one of the of the 30 voices over time. up to a big chord spa&ing NOTE! most recognizable pieces of computer-generated Observe the thr% stages multiple octaves and giving a sound ever designed: The THX D#p Note! the sound goes through! sense of epic resolution and a#ival -- whoa. Designed and progra(ed in 1982 by James Andy M&rer (also a founding member of )RMA), the D#p Note was first introduced 2 "CONVERGENCE" 1800 Hz with the 1983 premier of Return of the Jedi and has b#n heard in countle' THX The voices sm$thly glide toward trailers for movies and video games! their respective target frequencies. Overa%, 30 voices converge on 9 When Andy created the D#p Note, he was an employ# target frequencies in a giant 30-way of Lucasfilm's Computer Division (which not only led to gli"ando, building a sense of 1500 Hz THX but eventua!y Pixar). THX creator TOM Holman intense motion -- "it's ha#ening!" asked Andy to create a sound logo that "Comes out of nowhere and gets rea$y, rea$y big." in 1982, it t"k Andy M"rer 325 lines of C code ru&ing on a specialized hardware and software audio signal proce%or.