Field Verification of the Piscassic and Lower Lamprey River Watersheds Wildlife Habitat GIS Modeling Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Restored Access Leads to Record by Runs up the Lamprey River Michael Dionne

RETURN OF THE RIVER HERRING RESTORED ACCESS LEADS TO RECORD BY RUNS UP THE LAMPREY RIVER MICHAEL DIONNE ate one afternoon in mid-April, I decided to check on the fish ladder, I was astonished at what I saw. River herring, lots of newly constructed fish ladder at Wiswall Dam in Durham, river herring! In the 10 short minutes I visited the fish ladder, I to be sure it was ready to pass any river herring that made witnessed at least 60 river herring emerging from the fish ladder the journey upstream. The annual migration of river her- exit on their way to their historic spawning grounds. And to think L ring to New Hampshire’s seacoast had started just the day these remarkable fish made the 3.6-mile journey from Newmarket before, with about 2,400 fish ascending the fish ladder at the head- in just one day! Even more astounding, these are the first fish to of-tide dam on the Lamprey River in Newmarket. As I approached swim past this location since a dam was first built here in 1830. the top of the fish ladder on that sunny afternoon, I saw two dark fish dart into the impoundment. Alewives and Bluebacks “Could it be?” I thought to myself. “Are river herring already River herring are actually comprised of two species of fish, the here?” As I quickly stepped up to the fence next to the dam and alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus) and the blueback herring (Alosa © ERIC ENGBRETSON 8 July/August 2013 • aestivalis). The appearance and life history of these two species while the juveniles spend the remainder of spring and a good are so similar that we group them together as “river herring” and portion of the summer in freshwater, feeding and growing. -

New Hampshire Rivers Management and Protection Program Biennial Report: Fiscal Years 2016-2017

New Hampshire Rivers Management and Protection Program Biennial Report: Fiscal Years 2016-2017 DRAFT The purpose of the Rivers Management and Protection Program (RMPP), established in 1988 and defined in RSA 483, is to protect certain New Hampshire rivers, called designated rivers, for their outstanding natural and cultural resources. The program is administered by the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services (NHDES) and uses a two-tier approach to manage and protect rivers at the state and local levels through the advisement of the state Rivers Management Advisory Committee (RMAC) and the Local River Management Advisory Committees (LACs). As of June 30, 2017, there were 18 rivers or river segments designated under RSA 483 totaling 990 river miles and representing 126 towns, places, and State Parks. These 18 rivers had over 200 volunteers in 21 LACs overseeing their management (the Connecticut River has multiple LACs due to its length). One full time and one part-time staff administer the Rivers Program, with an additional full-time staff administering the Instream Flow Program. The RMPP is primarily a volunteer-based program, and most of its achievements are the result of the work of the volunteer members of the RMAC and the LACs. The Governor and Council appointed RMAC is composed of seventeen members representing various business, conservation, public service, and state agency interests. LAC members are nominated by their local communities and appointed by the NHDES Commissioner, and represent interests including local government, business, conservation, recreation, agriculture, and riparian landowners. The time spent by RMAC and LAC volunteers on river protection efforts during Fiscal Years 2016-2017 totals approximately 37,262 hours, and is valued at $927,830.1 RMPP Accomplishments Warner River Nominated to the RMPP: The nomination of the Warner River, flowing through the towns of Bradford, Warner, Sutton, Webster, and Hopkinton, was submitted on June 1, 1 Calculated using the 2016 New Hampshire volunteer rate of $24.90 per hour. -

Our Maritime Heritage a Piscataqua Region Timeline

OUR MARITIME HERITAGE A PISCATAQUA REGION TIMELINE 14,000 years ago Glaciers melted 8,000 years ago Evidence of seasonal human activity along the Lamprey River 2,000 years ago Sea level reached today’s current levels 9approximately) Before 1600 Native Americans had been in area for thousands of years Early 1400s Evidence of farming by Natives in Eliot 1500s European explorers and fishermen visiting and trading in region 1524 Verrazano became first European to describe the Maine coast Early 1600s English settlements at Exeter, Dover, Hampton, and Kittery Early 1600s Native population devastated by European diseases 1602 Earliest landfall on the coast in York (claimed) 1607 Popham Colony established at Maine’s Kennebec River; lasts barely a year 1603 Martin Pring arrived, looking for sassafras FISHING, BEAVER TRADE 1614 Captain John Smith created the first map of the region 1620 Pilgrims from the MAYFLOWER settled at Plimoth in Massachusetts Bay 1622-23 King James granted charters to Mason and Georges for Piscataqua Plantations 1623 Fishing settlements established at Odiorne Point and Dover (Hilton) Point 1623 Kittery area is settled; incorporated in 1647, billed as oldest town in Maine 1623 Simple earthen defense was built at Fort Point (later Fort William and Mary) 1624 Captain Christopher Levitt sailed up the York River 1630 Strawbery Banke settled by Captain Neal and band of Englishmen 1630 Europeans first settle below the falls on the Salmon Falls River 1631 Stratham settled by Europeans under Captain Thomas Wiggin 1632 Fort William -

Stocking Report, May 14, 2021

Week Ending May 14, 2021 Town Waterbody Acworth Cold River Alstead Cold River Amherst Souhegan River Andover Morey Pond Antrim North Branch Ashland Squam River Auburn Massabesic Lake Barnstead Big River Barnstead Crooked Run Barnstead Little River Barrington Nippo Brook Barrington Stonehouse Pond Bath Ammonoosuc River Bath Wild Ammonoosuc River Belmont Pout Pond Belmont Tioga River Benton Glencliff Home Pond Bethlehem Ammonoosuc River Bristol Newfound River Brookline Nissitissit River Brookline Spaulding Brook Campton Bog Pond Carroll Ammonoosuc River Columbia Fish Pond Concord Merrimack River Danbury Walker Brook Danbury Waukeena Lake Derry Hoods Pond Dorchester South Branch Baker River Dover Cocheco River Durham Lamprey River Week Ending May 14, 2021 Town Waterbody East Kingston York Brook Eaton Conway Lake Epping Lamprey River Errol Clear Stream Errol Kids Pond Exeter Exeter Reservoir Exeter Exeter River Exeter Little River Fitzwilliam Scott Brook Franconia Echo Lake Franconia Profile Lake Franklin Winnipesaukee River Gilford Gunstock River Gilsum Ashuelot River Goffstown Piscataquog River Gorham Peabody River Grafton Mill Brook Grafton Smith Brook Grafton Smith River Greenland Winnicut River Greenville Souhegan River Groton Cockermouth River Groton Spectacle Pond Hampton Batchelders Pond Hampton Taylor River Hampton Falls Winkley Brook Hebron Cockermouth River Hill Needle Shop Brook Hill Smith River Hillsborough Franklin Pierce Lake Kensington Great Brook Week Ending May 14, 2021 Town Waterbody Langdon Cold River Lee Lamprey River -

Appendix A: Fish

Appendix A: Fish Alewife Alosa pseudoharengus Federal Listing State Listing SC Global Rank G5 State Rank S5 High Regional Status Photo by NHFG Justification (Reason for Concern in NH) Alewife numbers have declined significantly throughout their range. Commercial landings of river herring, a collective term for alewives and blueback herring, have declined by 93% since 1985 (ASMFC 2009). Dams severely limit accessible anadromous fish spawning habitat, and alewives must use fish ladders for access to most spawning habitat in New Hampshire during spring spawning runs. River herring are a key component of freshwater, estuarine, and marine food webs (Bigelow and Schroeder 1953). They are an important source of prey for many predators, and they contribute nutrients to freshwater ecosystems (Macavoy et al. 2000). Distribution The alewife is found in Atlantic coastal rivers from Newfoundland to North Carolina. It has been introduced into a number of inland waterbodies (Scott and Crossman 1973). In New Hampshire, alewives migrate into the Merrimack River and the seacoast drainages (Scarola 1987). Habitat Adult alewives migrate from the ocean into freshwater spawning habitats with slow moving water, including riverine oxbows, lakes, ponds, and mid‐river sites (Scott and Crossman 1973). Juveniles remain in freshwater until late summer and early fall when they migrate downstream into estuaries and eventually to the ocean. There is little information available on alewife movement and habitat use in the ocean. New Hampshire Wildlife Action Plan Appendix A Fish-21 Appendix A: Fish NH Wildlife Action Plan Habitats ● Large Warmwater Rivers ● Warmwater Lakes and Ponds ● Warmwater Rivers and Streams Distribution Map Current Species and Habitat Condition in New Hampshire Coastal Watersheds: Alewife populations in the coastal watersheds are generally stable or increasing in recent years at fish ladders where river herring and other diadromous species have been monitored since 1979. -

Lamprey River Water Management Plan

NHDES-R-WD-11-9 Lamprey River Water Management Plan 28 August 2013 This Page Intentionally Blank Lamprey River Water Management Plan Prepared by Watershed Management Bureau NH Department of Environmental Services With contractor assistance from Normandeau Associates, Inc., University of New Hampshire, and Rushing Rivers Institute NHDES PO Box 95 - 29 Hazen Drive Concord, NH 03302-0095 http://www.des.state.nh.us/rivers/instream/ Thomas S. Burack Commissioner Vicki V. Quiram Assistant Commissioner Harry T. Stewart. P. E., Director Water Division iii This Page Intentionally Blank iv Table of Contents Page Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ ix LAMPREY RIVER WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN .................................................................. 1 I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 A. Definition of Protected Instream Flows and Identification of Protected Entities 2 B. Natural Flow Paradigm 3 C. Protected Flow Assessment for Flow-Dependent, Instream Public Uses 4 D. Lamprey River Protected Instream Flows 5 1. Protected Instream Flow for Boating ....................................................................................................................... 5 2. Protected Instream Flows for Fish and Aquatic Life ............................................................................................... 6 3. Protected Instream -

THE FLOODS of MARCH 1936 Part 1

If you do jno*-Be <l this report after it has served your purpose, please return it to the Geolocical -"" Survey, using the official mailing label at the end UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR THE FLOODS OF MARCH 1936 Part 1. NEW ENGLAND RIVERS Prepared in cooperation withihe FEDERAL EMERGENCY ADMINISTRATION OF PUBLIC WORKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 798 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Water-Supply Paper 798 THS^LOODS OF MARCH 1936 PART 1. NEW ENGLAND RIVERS NATHAN C. GROVER Chief Hydraulic Engineer Prepared in cooperation with the FEDERAL EMERGENCY ADMINISTRATION OF PUBLIC WORKS UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1937 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 70 cents CONTENTS Page Abstract............................................................. 1 Introduction......................................................... 2 Authorization........................................................ 5 Administration and personnel......................................... 5 Acknowledgments...................................................... 6 General features of the storms....................................... 7 Floods of the New England rivers....................................o 12 Meteorologic and hydrologic conditions............................... 25 Precipitation records............................................ 25 General f>!-................................................... 25 Distr<* '-utlon -

Piscataqua Area Place Names and History

PISCATAQUA AREA PLACE NAMES AND HISTORY by Sylvia Fitts Getchell Adams Point. Formerly known as Matthews Neck, q.v. Agamenticus. York. Originally the name applied by the Indians to what is now called York River. Early settlers used the term for the area about the river. [Used today only for Mount Agamenticus (in York)] Ambler’s Islands. Three small islands off Durham Point near the mouth of Oyster River. Ambush Rock. In Eliot. Where Maj. Chas. Frost was killed by Indians July 4, 1697 (about a mile N. of his garrison on his way home from Church at Great Works). Appledore Island. Named for a Parish in Northam, England. Early named Hog Island. Largest of the Isles of Shoals. Now in ME. [Name Appledore was used 1661-1679 for all the islands when they were briefly a township under Mass. Gov’t.] Arundel. See Cape Porpus. Acbenbedick River. Sometimes called the Little Newichawannock. Now known as Great Works River. First mills (saw mill and stamping mill) in New England using water power built here 1634 by carpenters sent to the colony by Mason. [Leader brothers took over the site (1651) for their mills. See also Great Works.] Ass Brook. Flows from Exeter into Taylor’s River. Atkinson’s Hill. In SW part of Back River District of Dover. Part in Dover, part in Madbury. Also known as Laighton’s Hill (Leighton’s). Back River. Tidal river W of Dover Neck. Back River District. Lands between Back River & Durham line from Cedar Point to Johnson’s Creek Bridge. Part now in Madbury, part in Dover. -

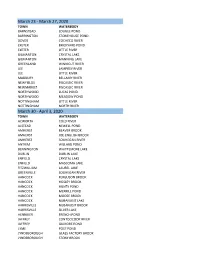

Stocking Report Through June 12, 2020

March 23 ‐ March 27, 2020 TOWN WATERBODY BARNSTEAD LOUGEE POND BARRINGTON STONEHOUSE POND DOVER COCHECO RIVER EXETER BRICKYARD POND EXETER LITTLE RIVER GILMANTON CRYSTAL LAKE GILMANTON MANNING LAKE GREENLAND WINNICUT RIVER LEE LAMPREY RIVER LEE LITTLE RIVER MADBURY BELLAMY RIVER NEWFIELDS PISCASSIC RIVER NEWMARKET PISCASSIC RIVER NORTHWOOD LUCAS POND NORTHWOOD MEADOW POND NOTTINGHAM LITTLE RIVER NOTTINGHAM NORTH RIVER March 30 ‐ April 3, 2020 TOWN WATERBODY ACWORTH COLD RIVER ALSTEAD NEWELL POND AMHERST BEAVER BROOK AMHERST JOE ENGLISH BROOK AMHERST SOUHEGAN RIVER ANTRIM WILLARD POND BENNINGTON WHITTEMORE LAKE DUBLIN DUBLIN LAKE ENFIELD CRYSTAL LAKE ENFIELD MASCOMA LAKE FITZWILLIAM LAUREL LAKE GREENVILLE SOUHEGAN RIVER HANCOCK FERGUSON BROOK HANCOCK HOSLEY BROOK HANCOCK HUNTS POND HANCOCK MERRILL POND HANCOCK MOOSE BROOK HANCOCK NUBANUSIT LAKE HARRISVILLE NUBANUSIT BROOK HARRISVILLE SILVER LAKE HENNIKER FRENCH POND JAFFREY CONTOOCOOK RIVER JAFFREY GILMORE POND LYME POST POND LYNDEBOROUGH GLASS FACTORY BROOK LYNDEBOROUGH STONY BROOK MARLBOROUGH STONE POND MARLOW GUSTIN POND MASON MASON BROOK MERRIMACK SOUHEGAN RIVER MILFORD OSGOOD BROOK MILFORD PURGATORY BROOK MILFORD SOUHEGAN RIVER NELSON CENTER POND NEW LONDON SUNAPEE LAKE, LITTLE PETERBOROUGH CONTOOCOOK RIVER PETERBOROUGH NUBANUSIT BROOK STODDARD COLD SPRING POND STODDARD GRANITE LAKE SULLIVAN CHAPMAN POND SULLIVAN OTTER BROOK SUTTON KEZAR LAKE SWANZEY SWANZEY LAKE WALPOLE CONNECTICUT RIVER WARNER STEVENS BROOK WARNER WARNER RIVER WEARE MT WILLIAM POND WEARE PERKINS POND WEBSTER WINNEPOCKET -

Fish Surveys

Lamprey River Watershed Fish Surveys Report to the Lamprey River Local Advisory Committee New Hampshire Fish and Game Inland Fisheries Fish Conservation Program July 30, 2012 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 4 METHODS ......................................................................................................................... 5 Study Area ...................................................................................................................... 5 Fish surveys .................................................................................................................... 6 RESULTS / DISCUSSION................................................................................................. 9 Habitat Summary .......................................................................................................... 13 Comparison to previous surveys ................................................................................... 14 Species of Concern ....................................................................................................... 15 Eastern Brook Trout ................................................................................................. 15 Bridle shiner .............................................................................................................. 18 Banded sunfish, Redfin Pickerel, and Swamp Darter ............................................... 22 Diadromous -

American Shad Habitat Plan for New Hampshire Coastal Rivers

New Hampshire Fish and Game Department Marine Fisheries Division American Shad Habitat Plan for New Hampshire Coastal Rivers Submitted to the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission as a requirement of Amendment 3 to the Interstate Management Plan for Shad and River Herring Approved February 6, 2014 American Shad Habitat Plan for New Hampshire Coastal Rivers New Hampshire Fish & Game Department Marine Fisheries Division September 2013 This habitat plan is submitted by the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department as a requirement of Amendment 3 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Shad and River Herring. Historically populations of American shad have been present in the coastal waters of New Hampshire including the Merrimack River, Connecticut River, and major tributaries of Great Bay Estuary. However, over the past 30 years of monitoring by the Department the number of returning American shad adults has been highly variable and in significant decline over the past 10 years. This plan outlines the current and historic habitat for American shad within the state. The greatest threat identified to the successful restoration of the species is the presence of dams along the rivers. Dams fragment the habitat and may further reduce the numbers entering fresh water due to the absence of a fish passage structure or poor passage efficacy for American shad of the existing structure. 1) Habitat Assessment a) Spawning Habitat Exeter River: i) Amount of historical in-river and estuarine spawning habitat: The headwaters of the Exeter River are in Chester, NH and the river flows approximately 75.7 rkm into Great Bay in Newfields, NH. -

The Lamprey River Flows 47 Miles from the Hills of Northwood to The

The Richard Schanda Conservation Park WHERE THE LAMPREY RIVER MEETS GREAT BAY The Lamprey River flows Three-masted schooners were sailed to Newmarket 47 miles from the hills of and other river towns to take on fresh water and Northwood to the McCallen Dam to transport supplies and manufactured goods and continues as a tidal river to along the coast and across the ocean. Great Bay and eventually to the Atlantic Today, Newmarket’s mill buildings Ocean. Varied habitats define the river and have new uses: housing, the land that surrounds it: forests, open fields, businesses, and the arts. quiet backwaters, flood plains, rushing rapids, and wetlands. The Lamprey and five smaller rivers (Cocheco, Bellamy, Oyster, Exeter/Squamscot, and Winnicut) flow into the Great Bay Estuary, where fresh, inland water meets the salty sea. The Lamprey’s water continues to Little Bay, down the fast Piscataqua River, past Portsmouth and finally into Waterways were the major transportation routes the Gulf of Maine, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. of the 1600s through the 1800s. Piscataqua (Above) Map of Newmarket Conservation Lands Water always connects places and people. gundalows, unique to this area, carried bulk goods (To the right) Lamprey River Watershed and occasionally passengers through the shallower For thousands of years, regions of the Great Bay Estuary and the coast. the Squamscot and Wampanoeg tribes gathered at the river to harvest oysters and clams, plant gardens, and catch fish with their weirs. Newmarket is conserving land along the Lamprey and elsewhere in the Not long after their arrival, European colonists town to help keep the river’s water clean for today and future generations.