Pacific and Winter Wrens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terrestrial Ecology Enhancement

PROTECTING NESTING BIRDS BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES FOR VEGETATION AND CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS Version 3.0 May 2017 1 CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 3 2.0 BIRDS IN PORTLAND 4 3.0 NESTING BEHAVIOR OF PORTLAND BIRDS 4 3.1 Timing 4 3.2 Nesting Habitats 5 4.0 GENERAL GUIDELINES 9 4.1 What if Work Must Occur During Avoidance Periods? 10 4.2 Who Conducts a Nesting Bird Survey? 10 5.0 SPECIFIC GUIDELINES 10 5.1 Stream Enhancement Construction Projects 10 5.2 Invasive Species Management 10 - Blackberry - Clematis - Garlic Mustard - Hawthorne - Holly and Laurel - Ivy: Ground Ivy - Ivy: Tree Ivy - Knapweed, Tansy and Thistle - Knotweed - Purple Loosestrife - Reed Canarygrass - Yellow Flag Iris 5.3 Other Vegetation Management 14 - Live Tree Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Snag Removal - Shrub Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Grassland Mowing and Ground Cover Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Controlled Burn 5.4 Other Management Activities 16 - Removing Structures - Manipulating Water Levels 6.0 SENSITIVE AREAS 17 7.0 SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS 17 7.1 Species 17 7.2 Other Things to Keep in Mind 19 Best Management Practices: Avoiding Impacts on Nesting Birds Version 3.0 –May 2017 2 8.0 WHAT IF YOU FIND AN ACTIVE NEST ON A PROJECT SITE 19 DURING PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION? 9.0 WHAT IF YOU FIND A BABY BIRD OUT OF ITS NEST? 19 10.0 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS FOR AVOIDING 20 IMPACTS ON NESTING BIRDS DURING CONSTRUCTION AND REVEGETATION PROJECTS APPENDICES A—Average Arrival Dates for Birds in the Portland Metro Area 21 B—Nesting Birds by Habitat in Portland 22 C—Bird Nesting Season and Work Windows 25 D—Nest Buffer Best Management Practices: 26 Protocol for Bird Nest Surveys, Buffers and Monitoring E—Vegetation and Other Management Recommendations 38 F—Special Status Bird Species Most Closely Associated with Special 45 Status Habitats G— If You Find a Baby Bird Out of its Nest on a Project Site 48 H—Additional Things You Can Do To Help Native Birds 49 FIGURES AND TABLES Figure 1. -

IMBCR Report

Integrated Monitoring in Bird Conservation Regions (IMBCR): 2015 Field Season Report June 2016 Bird Conservancy of the Rockies 14500 Lark Bunting Lane Brighton, CO 80603 303-659-4348 www.birdconservancy.org Tech. Report # SC-IMBCR-06 Bird Conservancy of the Rockies Connecting people, birds and land Mission: Conserving birds and their habitats through science, education and land stewardship Vision: Native bird populations are sustained in healthy ecosystems Bird Conservancy of the Rockies conserves birds and their habitats through an integrated approach of science, education and land stewardship. Our work radiates from the Rockies to the Great Plains, Mexico and beyond. Our mission is advanced through sound science, achieved through empowering people, realized through stewardship and sustained through partnerships. Together, we are improving native bird populations, the land and the lives of people. Core Values: 1. Science provides the foundation for effective bird conservation. 2. Education is critical to the success of bird conservation. 3. Stewardship of birds and their habitats is a shared responsibility. Goals: 1. Guide conservation action where it is needed most by conducting scientifically rigorous monitoring and research on birds and their habitats within the context of their full annual cycle. 2. Inspire conservation action in people by developing relationships through community outreach and science-based, experiential education programs. 3. Contribute to bird population viability and help sustain working lands by partnering with landowners and managers to enhance wildlife habitat. 4. Promote conservation and inform land management decisions by disseminating scientific knowledge and developing tools and recommendations. Suggested Citation: White, C. M., M. F. McLaren, N. J. -

Comprehensive Conservation Plan Benton Lake National Wildlife

Glossary accessible—Pertaining to physical access to areas breeding habitat—Environment used by migratory and activities for people of different abilities, es- birds or other animals during the breeding sea- pecially those with physical impairments. son. A.D.—Anno Domini, “in the year of the Lord.” canopy—Layer of foliage, generally the uppermost adaptive resource management (ARM)—The rigorous layer, in a vegetative stand; mid-level or under- application of management, research, and moni- story vegetation in multilayered stands. Canopy toring to gain information and experience neces- closure (also canopy cover) is an estimate of the sary to assess and change management activities. amount of overhead vegetative cover. It is a process that uses feedback from research, CCP—See comprehensive conservation plan. monitoring, and evaluation of management ac- CFR—See Code of Federal Regulations. tions to support or change objectives and strate- CO2—Carbon dioxide. gies at all planning levels. It is also a process in Code of Federal Regulations (CFR)—Codification of which the Service carries out policy decisions the general and permanent rules published in the within a framework of scientifically driven ex- Federal Register by the Executive departments periments to test predictions and assumptions and agencies of the Federal Government. Each inherent in management plans. Analysis of re- volume of the CFR is updated once each calendar sults helps managers decide whether current year. management should continue as is or whether it compact—Montana House bill 717–Bill to Ratify should be modified to achieve desired conditions. Water Rights Compact. alternative—Reasonable way to solve an identi- compatibility determination—See compatible use. -

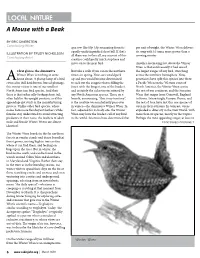

A Mouse with a Beak

LOCAL NATURE A Mouse with a Beak BY ERIC DINERSTEIN Contributing Writer sparrow-like klip-klip emanating from its per unit of weight, the Winter Wren delivers equally undistinguished short bill. If that’s its song with 10 times more power than a ILLUSTRATION BY TRUDY NICHOLSON all there was to the call, my account of this crowing rooster. Contributing Artist creature could pretty much stop here and move on to the next bird. Another fascinating fact about the Winter Wren is that until recently it had one of t frst glance, the diminutive But take a walk if you can in the northern the largest ranges of any bird, stretching Winter Wren is nothing to write forests in spring. Your ears would perk across the northern hemisphere. Now, home about. A plump lump of a bird up and you would become determined geneticists have split this species into three: Acovered in dull dark brown, barred plumage, to seek out the songster that is flling the a Pacifc Wren on the Western coast of this winter visitor is one of our smallest forest with the longest, one of the loudest, North America, the Winter Wren across North American bird species. And then and certainly the richest notes uttered by the rest of our continent, and the Eurasian there is that rather silly-looking short tail, any North American species. Tere on a Wren that ranges from Cornwall, England ofen held in the upright position, as if this branch, announcing, “this is my territory”, to Korea. Interestingly, Europe, Russia, and appendage got stuck in the manufacturing is the creature we nonchalantly pass over the rest of Asia have just this one species of process. -

Troglodytes Troglodytes

Troglodytes troglodytes -- (Linnaeus, 1758) ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- PASSERIFORMES -- TROGLODYTIDAE Common names: Winter Wren; Wren European Red List Assessment European Red List Status LC -- Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) EU27 regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) In Europe this species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). The population trend appears to be stable, and hence the species does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern in Europe. Within the EU27 this species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). Despite the fact that the population trend appears to be decreasing, the decline is not believed to be sufficiently rapid to approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern in the EU27. Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Albania; Andorra; Armenia; Austria; Azerbaijan; Belarus; Belgium; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bulgaria; Croatia; Cyprus; Czech Republic; Denmark; Faroe Islands (to DK); Estonia; Finland; France; Georgia; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Iceland; Ireland, Rep. -

Highland Lakes Steward

Highland Lakes Steward HIGHLAND LAKES CHAPTER August 2011 Volume 2, Issue 8 MISSION CORK TREES by Billy Hutson The Texas Master Naturalist program is Undoubtedly you are think- a natural resource- ing of other more important based volunteer train- things when you uncork a bot- ing and development tle of wine but have you ever program sponsored statewide by Texas wondered where corks come AgriLife Extension from? Well they come from the and the Texas Parks cork tree "Quercus Suber" and Wildlife Depart- which means slow growing. The ment. The mission of the cork trees I am talking about program is to develop grow in SW Europe and NW a corps of well- Africa but in the Spain and Por- informed volunteers tugal area they are carefully who provide educa- cared for by the cork producing tion, outreach, and service dedicated to industry. I remember seeing the beneficial manage- one in the postage stamp back- ment of natural re- yard of a friends home in south- sources and natural ern California where it took up areas within their communities for the the entire space, so they evidently like that are 25 years old and they are very carefully state of Texas climate also. Maybe we could grow them in monitored. In fact they cannot be legally cut Texas!! There are other cork trees that down in Portugal and the industry in OFFICERS grow in China and Australia but the wine Europe employs some 30,000 people. President cork industry is basically located in Spain Since the process is only 40% efficient Billy Hutson and Portugal. -

News and Notes

N E W S A N D N O T E S by Paul Hess A New “Pacific Wren”? cordant in each individual tested (Molecular Ecology In Russia it is Krapivnik, in Poland it is strzyz˙yk, in Germany 17:2691–2705). it is der Zaunkönig, in Britain it is the Wren. By whatever Wrens identified as pacificus and hiemalis by DNA consis- name, our Winter Wren is one of the most widespread song- tently sang either a distinctly pacificus or a distinctly hiemalis birds, breeding in boreal forests around the world. Unre- song—each singing type corresponding to typical songs in solved is how many species Troglodytes troglodytes represents. western and eastern populations away from the contact At least two, in the view of David P. L. Toews and Darren zone. The differences are recognizable to the human ear, and E. Irwin. They recommend species status for western North they are quantitatively evident in the samples tested: pacifi- America’s pacificus subspecies group in a formal proposal to cus higher in maximum and mean frequency, and faster in the American Ornithologists’ Union North American Classi- switching between relatively high and low notes. No signif- fication Committee (the “Check-list Committee”) in 2009. icant quantitative differences emerged in length, minimum The Committee’s decision will be announced in the annual frequency, and percentage of silence between notes. Check-list supplement in the July 2010 issue of The Auk. The call notes also differ between pacificus and hiemalis— The proposal stems from the authors’ discovery of an area a distinction the authors recognized but have not yet ana- in northeastern British Columbia where both pacificus and lyzed. -

Cryptic Speciation in a Holarctic Passerine Revealed by Genetic and Bioacoustic Analyses

Molecular Ecology (2008) 17, 2691–2705 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03769.x CBlackwell Publrishing Lytd ptic speciation in a Holarctic passerine revealed by genetic and bioacoustic analyses DAVID P. L. TOEWS and DARREN E. IRWIN Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, 6270 University Blvd., Vancouver, BC Canada V6T 1Z4 Abstract There has been much controversy regarding the timing of speciation events in birds, and regarding the relative roles of natural and sexual selection in promoting speciation. Here, we investigate these issues using winter wrens (Troglodytes troglodytes), an unusual example of a passerine with a Holarctic distribution. Geographical variation has led to speculation that the western North American form Troglodytes troglodytes pacificus might be a distinct biological species compared to those in eastern North America (e.g. Troglodytes troglodytes hiemalis) and Eurasia. We located the first known area in which both forms can be found, often inhabiting neighbouring territories. Each male wren in this area sings either western or eastern song, and the differences in song are as distinct in the contact zone as they are in allopatry. The two singing types differ distinctly in mitochondrial DNA sequences and amplified fragment length polymorpism profiles. These results indicate that the two forms are reproductively isolated to a high degree where they co-occur and are therefore separate species. DNA variation suggests that the initial split between the two species occurred before the Pleistocene, quite long ago for sister species in the boreal forest. Surprisingly, the two forms are similar in morphometric traits and habitat characteristics of territories. These findings suggest that sexual selection played a larger role than habitat divergence in generating reproductive isolation, and raise the possibility that there are other such morphologically cryptic species pairs in North America. -

The Winter Birds Point Pelee National Park

THE WINTER BIRDS POINT PELEE NATIONAL PARK_ Indian and Affaires indiennes Northern Affairs et du Nord Parks Canada Pares Canada Point Pelee National Park Grassy Area Sand Beaches Marsh Cultivated Land Abandoned Orchard Area Red Cedar, Hackberry, Oak, Mixed Forest Elm, Basswood, Mixed Forest Willow, Poplar BeH Parkway 'I certainly never did hear so many birds singing in the winter. when we opened the door in the morning we were greeted by a regular chorus of bird song . .It was more like May than February." P. A. Taverneronavisit to Point Pelee, February, 1909. Taverner Manuscripts No. 1; Rare Book Room, Library, Univer sity of Toronto. All plants and animals, and other natural features of this Park are protected and preserved for all who may come this way. Please do not remove or damage them. The Winter Birds of Point Peiee National Park Ontario by George M.Stirrett, Ph.D. Formerly Chief Parks Naturalist National Parks Service Ottawa, 1973 © Crown Copyright reserved or through your bookseller Available by mail from Information Canada, Price: 500 Catalogue No. R63-7072 Ottawa, and at the following Information Canada bookshops: Price subject to change without notice HALIFAX Information Canada 1683 Barrington Street Ottawa, 1973. MONTREAL Published by Parks Canada underauthority 640 St. Catherine Street West of the Hon. Jean Chretien, PC, MP., Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern OTTAWA Development. 171 Slater Street IAND Publication No. QS-2090-OOO-EE-AI TORONTO 221 Yonge Street WINNIPEG 393 Portage Avenue VANCOUVER 800 Granville Street -

Chaffinch and Winter Wren Podcast.Pages

podcasts Encyclopedia of Life eol.org Chaffinch and Winter Wren Podcast and Scientist Interview Fringilla coelebs, Troglodytes troglodytes Every morning when he walks the dog, retired professor of natural history Peter Slater can identify as many as thirty birds by their song alone. On a walk in a Scottish town with Ari Daniel Shapiro, Slater explains what two common songsters, the chaffinch and winter wren, are singing about, and how even city dwellers can learn to “bird by ear” in their own neighborhoods, with rewarding results. Transcript Ari: From the Encyclopedia of Life, this is: One Species at a Time. I’m Ari Daniel Shapiro. Slater: Well, I’m going to take you out to show you a few of our nice, local native birds and to listen to them particularly. We’ll go across the street here, I think. Ari: Peter Slater was professor of natural history at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. Slater: Professor of natural history is a lovely old Scottish title. Ari: He retired a couple years back but almost 10 years ago, Peter was my advisor for my Master’s degree. When I was in Scotland recently, I took him up on his offer to go on a local bird walk. We started right on Peter’s doorstep. Slater: I take my dog for a walk every morning in St. Andrews and I count all the birds that I see or hear. And I usually get up to 20 or 30 different sorts of bird. Actually, quite a few of those I hardly ever see. -

Conspecific Nest Aggression of The

CONSPECIFIC NEST AGGRESSION OF THE PACIFIC WREN ON VANCOUVER ISLAND, BRITISH COLUMBIA ANN NIGHTINGALE and RON MELCER, JR., Rocky Point Bird Observatory, Suite #170, 1581-H Hillside Avenue, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada V8T 2C1; [email protected] ABSTRACT: Five of the ten wren species in North America are known to destroy nests of conspecifics. These include the Cactus Wren (Campylorhynchus brunneica- pillus), Bewick’s Wren (Thryomanes bewickii), Sedge Wren (Cistothorus platensis), Marsh Wren (Cistothorus palustris), and House Wren (Troglodytes aedon). However, none of the Winter Wren complex, recently split as the Winter Wren (Troglodytes hiemalis), Pacific Wren (T. pacificus), and Eurasian Wren (T. troglodytes), have been documented to do so in experiments or by observation of natural behavior. Here we present a detailed chronology of a nesting of the Pacific Wren—the first report of conspecific nest aggression in the Winter Wren complex. On 15 May 2011, in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, a Pacific Wren approached another’s nest under video surveillance and removed two 9-day-old chicks. The nonparental adult returned to the nest, apparently attempting to kill and/or and remove the remaining two chicks, several times over 4.75 hours but was not successful. Although our findings are limited to a single event, they are consistent with those of other wrens. Birds are known to destroy the nests and eggs or remove the young from nests of other species, as well as conspecifics, to reduce competition for nests, food, perches, and, in polygynous species, for the male’s parental care (Fox 1975, Verner 1975, Picman 1977a, Jones 1982). -

Nesting of the Winter Wren (Troglodytes Hiemalis) in the Black Mountains of North Carolina Ryan S

Nesting of the Winter Wren (Troglodytes hiemalis) in the Black Mountains of North Carolina Ryan S. Mays1 and Aubrey O. Neas, Jr.2 1Blacksburg, Virginia; [email protected] 2Big Island, Virginia On 19 June 2010, the authors visited Balsam Gap in the Black Mountains of North Carolina. About 17:00 EDT, while walking down the forested, southwestern slope of Bearwallow Stand Ridge between the Mountains-to-Sea hiking trail and the Blue Ridge Parkway, just within Buncombe County, we saw a Winter Wren (Troglodytes hiemalis) flush suddenly about a meter ahead of us and quickly disappear in the undergrowth. Shortly afterward, Mays found the well-concealed, dome-shaped nest from which the bird had evidently flown. The nest was placed 0.9 m from the ground amongst the southwest-facing upturned roots of a large yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis) that appeared to have fallen several years earlier. It was tucked in a cavity formed by large, divergent roots at the base of the fallen tree and was partially sheltered from above by several strips of loose bark and clumps of overhanging soil, moss, and debris adhering to other roots and rootlets. Growing on the wood just below the base of the nest was a small polypore fungus, tentatively identified as Piptoporus betulinus. The exterior of the nest was composed entirely of green mosses and red spruce twigs, with perhaps a few Fraser fir twigs intermixed. Its outer dimensions were estimated as follows: height 12-14 cm, width 11-13 cm. Mays carefully inspected the nest proper and found that it contained six white eggs.