Boctot of $T|Tu)S(Opi)P Political Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume Xlv, No. 3 September, 1999 the Journal of Parliamentary Information

VOLUME XLV, NO. 3 SEPTEMBER, 1999 THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION VOL. XLV NO.3 SEPTEMBER 1999 CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL NOTE 281 SHORT NOTES The Thirteenth Lok Sabha; Another Commitment to Democratic Values -LARRDIS 285 The Election of the Speaker of the Thirteenth Lok Sabha -LARRDIS 291 The Election of the Deputy Speaker of the Thirteenth Lok Sabha -LARRDIS 299 Dr. (Smt.) Najma Heptulla-the First Woman President of the Inter-Parliamentary Union -LARRDIS 308 Parliamentary Committee System in Bangladesh -LARRDIS 317 Summary of the Report of the Ethics Committee, Andhra Pradesh Legislative Assembly on Code of Conduct for Legislators in and outside the Legislature 324 PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES Conferences and Symposia 334 Birth Anniversaries of National Leaders 336 Indian Parliamentary Delegations Going Abroad 337 Bureau of Parliamentary Studies and Training 337 PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 339 SESSIONAl REVIEW State Legislatures 348 SUMMARIES OF BooKS Mahajan, Gurpreet, Identities and Rights-Aspects of Liberal Democracy in India 351 Khanna, S.K., Crisis of Indian Democracy 354 RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 358 ApPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Fourth Session of the Twelfth lok Sabha 372 II. Statement showing the work transacted during the One Hundred and Eighty-sixth Session of the Rajya Sabha 375 III. Statement showing the activities of the legislatures of the States and the Union territories during the period 1 April to 30 June 1999 380 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament and assented to by the President during the period 1 April to 30 June 1999 388 V. -

Glosario Terminos Migracion.Pdf

2 >>> Words Do Matter Migration has moved high on the international agenda; it is now the focus of sensitive debates and growing media attention in a variety of contexts. Intense interest is shown in specific issues which have only emerged fully in recent years: the situation of internally displaced persons, the dynamics of a `migration-development nexus’, or the consequences of environmental change on human displacement. Meanwhile, the future of international refugee protection and standards of national asylum policies appears fragile and uncertain. An extensive terminology has evolved to cover standing and emerging issues as they also relate to the larger fields of human rights and development. This handbook takes stock of the present use of some selected terms and concepts. It is designed to be accessible to a general public which may not be familiar with the detailed discussions in the field of refugee and migration policy. Civil society and the business sector play an increasingly important role in migration, and we also hope this handbook may be of use to them. Another intended audience is the media, firstly because many of the current perceptions on migration and refugees are shaped there, and secondly because terms are often incorrectly interpreted in media coverage. Words matter, for labels impact people’s views and inform policy responses. Brief comments are provided to complement the definitions proposed, to cover related terms or to highlight some issues behind the words. For the purpose of clarity, the definitions are listed under the following sections: Persons & Statuses to identify the fundamental distinctions between the various persons concerned. -

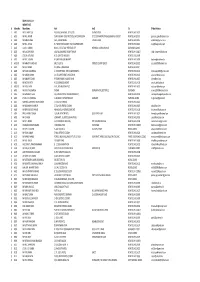

DELHI GOLF CLUB MEMBER LIST Sr Mem.No Mem.Name Add1 Add2 City E-Mail Address 1 A009 MR K

DELHI GOLF CLUB MEMBER LIST Sr Mem.No Mem.Name Add1 Add2 City E-Mail Address 1 A009 MR K. AMRIT LAL 90E, MALCHA MARG, IST FLOOR, CHANKYAPURI NEW DELHI 110021 2 A016 MR N.S. ATWAL GURU MEHAR CONSTRUCTION,S.M.COMPLEX,K-4 G.F.2,OLD RANGPURI ROAD,MAHIPAL PUR EXT. NEW DELHI-110037 [email protected] 3 A018 MR AMAR SINGH 16-A, PALAM MARG VASANT VIHAR, NEW DELHI 110057 [email protected] 4 A021 MR N.S. AHUJA B-7,WEST END COLONY, RAO TULARAM MARG NEW DELHI 110021 [email protected] 5 A022 COL K.C. ANAND BLOCK - 9,FLAT 302 HERITAGE CITY MEHRAULI GURGOAN ROAD GURGOAN 122002 6 A026 MR. ANOOP SINGH 16A, PALAM MARG VASANT VIHAR NEW DELHI- 110057 [email protected] 7 A028 LT GEN. AJIT SINGH R-51, GREATER KAILASH-I, NEW DELHI 110048 8 A032 MR M.T. ADVANI 6-SUNDER NAGAR MARKET, NEW DELHI 110003 [email protected] 9 A035 D1 MR AMARJIT SINGH (II) 680, C-BLOCK, FRIENDS COLONY (EAST) NEW DELHI-110025 [email protected] 10 A042 MR S.S. ANAND N-3,NDSE-1,RING ROAD, NEW DELHI-110049 11 A046 MR VIJAY AGGARWAL 2, CHURCH ROAD, DELHI CANTONMENT, NEW DELHI 110010 [email protected] 12 A051 MR ARJUN ASRANI 12, SFS APARTMENTS HAUZ KHAS NEW DELHI 110016 [email protected] 13 A056 MR AMARJIT SAHAY 9 POORVI MARG VASANT VIHAR NEW DELHI 110057 [email protected] 14 A058 MR ACHAL NATH A 51,NIZAMUDDIN EAST, NEW DELHI 110013 [email protected] 15 A059 D1 MR ATUL NATH A-51, NIZAMUDDIN EAST, NEW DELHI 110013 [email protected] 16 A060 MR. -

Annual Report 1999-2000

ANNUAL REPORT 1999-2000 CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION II FREEDOM FROM DISCRIMINATION III CIVIL LIBERTIES (A) HUMAN RIGHTS IN AREAS OF TERRORISM AND INSURGENCY (B) CUSTODIAL DEATH, RAPE AND TORTURE (C) ENCOUNTER DEATHS (D) VIDEO FILMING OF POST-MORTEM EXAMINATION AND REVISION OF AUTOPSY FORMS (E) VISITS TO POLICE LOCK-UPS (F) SYSTEMIC REFORMS: POLICE (G) SYSTEMIC REFORMS: PRISONS (H) HUMAN RIGHTS AND ADMINISTRATION OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE (I) VISIT TO JAILS (J) CONDITIONS OF REMAND HOMES (K) VISIT TO DETENTION CENTRES AND REFUGEE CAMPS (L) IMPROVEMENT OF FORENSIC SCIENCE LABORATORIES (M) LARGE VOLUME PARENTERALS: TOWARDS ZERO DEFECT IV. REVIEW OF LAWS, IMPLEMENTATION OF TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL INSTRUMENTS OF HUMAN RIGHTS (A) CHILD MARRIAGE RESTRAINT ACT, 1929 (B) PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS ACT, 1993 (C) IMPLEMENTATION OF TREATIES & OTHER INTERNATIONAL INSTRUMENTS V. RIGHTS OF THE CHILD: PREVENTION OF CONGENITAL MENTAL DISABILITIES VI. RIGHTS OF THE VULNERABLE (A) REHABILITATION OF PEOPLE DISPLACED BY MEGA PROJECTS (B) DISPENSATION OF RELIEF MEASURES TO THE ORISSA CYCLONE AFFECTED (C) BASIC FACILITIES TO PLANTATION WORKERSIN TAMIL NADU (D) EXPLOITATION OF TRIBALS BY LANDLORDS/MAFIA IN UTTAR PRADESH VII. ABOLITION OF CHILD LABOUR AND BONDED LABOUR (A) CHILD LABOUR IN VARIOUS INDUSTRIES (B) PREVENTING EMPLOYMENT OF CHILDREN BY GOVERNMENT SERVANTS: AMENDMENT OF SERVICE RULES VIII. QUALITY ASSURANCE IN MENTAL HOSPITALS IX MANUAL SCAVENGING X. PROBLEMS OF DENOTIFIED AND NOMADIC TRIBES XI. TORTURE CONVENTION AND DELHI SYMPOSIUM XII PROMOTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS LITERACY AND AWARENESS (A) MOBILISING THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM (B) HUMAN RIGHTS EDUCATION FOR POLICE PERSONNEL (C) HUMAN RIGHTS EDUCATION FOR PARA-MILITARY AND ARMED FORCES PERSONNEL (D) NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF HUMAN RIGHTS (E) INTERNSHIP SCHEME (F) TRAINING MATERIAL FOR STAFF OF HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSIONS (G) SEMINARS AND WORKSHOPS (H) PUBLICATIONS AND THE MEDIA (I) RESEARCH PROGRAMMES AND PROJECTS XIII. -

Abbas KA:Khwaja Ahmed Abbas Was a Well Known Indian Journalist, Writer and Film Director. He Wrote More Than Seventy Books

INDIA Abbas K.A: Khwaja Ahmed Abbas was a well known Ahalya Bai, Rani: She was the widowed Indian journalist, writer and film director. He wrote daughter-in-law of Malhar Rao Holkar. On the latter’s more than seventy books of which Tomorrow is death, Ahalya Bai became the ruler for thirty years Ours, Invitation to Immorality, Outside India, In- till her death in 1795. dian Look at America, Defeat for Death, I am Not Ahluwalia, Montek Singh: Montek Singh Ahluwalia an Island and The Walls of Glass are very famous. is the Deputy Chairman of Planning Commission. Abdul Gaffar Khan : He was a staunch Congress- He played keyrole in financial reforms in the 1990’s. man and a soldier of the Indian freedom struggle. Previously he was Finance Secretary and member He was also called Frontier Gandhi, because he of Planning Commission. organised the people of the North West Frontier Akilandam, P.V. : P.V. Akilandam, known as Akhilan, Province (NWFP) of undivided India (now merged was a famous Tamil poet. He won Jnanapith Award with Pakistan) on Gandhian principles. He was the for his Chithira Pavai. Nengin Alaikal, first foreigner to be awarded the Bharat Ratna, Vazhvininpam and Pavai Velaku are his famous India’s highest civilian award, in 1987. He was the works. founder of the movement known as Khudai Ali, Aruna Asaf: Indian freedom fighter, Mayor of Khidmatgars (Servants of God) in 1929. Delhi, 1958. A devoted socialist, radical in her views, Bharat Ratna’97. Abdul Khadar Maulavi, Vakkom: He was a social reformer who started the daily Swadeshabhimani Ali, Salim: Indian ornithologist known as ‘the Bird- with the editorship of K. -

21St CENTURY ROAD MAP for CONFLICT RESOLUTION

Seminar Report TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY ROADMAP FOR CONFLICT RESOLUTION BY THE UNITED NATIONS Seminar Coordinator: Lt. Col Sanjay Barshilia Centre for Land Warfare Studies RPSO Complex, Parade Road, Delhi Cantt, New Delhi-110010 Phone: 011-25691308; Fax: 011-25692347 email: [email protected]; website: www.claws.in The Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi, is an autonomous think tank dealing with contemporary issues of national security and conceptual aspects of land warfare, including conventional and sub-conventional conflicts and terrorism. CLAWS conducts research that is futuristic in outlook and policy-oriented in approach. © 2017, Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi All rights reserved The views expressed in this report are sole responsibility of the speaker(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India, or Integrated Headquarters of MoD (Army) or Centre for Land Warfare Studies. The content may be reproduced by giving due credit to the speaker(s) and the Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi. Printed in India by Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd. DDA Complex LSC, Building No. 4, 2nd Floor Pocket 6 & 7, Sector – C Vasant Kunj, New Delhi 110070 www.bloomsbury.com CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Detailed Report 6 Inaugural Session 6 Session I: The United Nations and Conflict Resolution 10 Session II: Contemporary Challenges to the United Nations 21 Concept Note 33 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The United Nations (UN) peace-keeping forces have been deployed to help monitor ceasefire agreements, create buffer zones or support complex military and civilian functions to help in the reconstruction of societies devastated by war. -

UN Invite.Cdr

DRAFT Celebrating Ten Years of Excellence in Institution Building You are cordially invited to a CONFERENCE on THE FUTURE OF THE UNITED NATIONS Chief Guests Dr. Sukehiro Hasegawa Ambassador Virendra Dayal Ambassador Chinmaya Gharekhan President, Global Peacebuilding Former Chef de Cabinet to the Former Permanent Representative of India to Association of Japan Secretary General of The United Nations the UN in Geneva and New York Former Special Representative of Former UN Secretary General Special Coordinator for the UN Secretary-General for Timor-Leste Occupied Territories in Gaza Date: Wednesday 20 February 2019 | Time: 9:30 am Venue: O.P. Jindal Global University Sonipat Narela Road, Sonipat - 131001, Haryana, NCR of Delhi, India RSVP: Programme 9:30 am Registration of Students and Faculty Members Inaugural Session: 10:00 am – 11:30 am Master of Ceremony: Ms. Tanushri More, B.A. LL.B. (2014), Jindal Global Law School Opening Remarks 10:00 am – 10:15 am Professor (Dr.) C. Raj Kumar, Founding Vice Chancellor, O. P. Jindal Global University Ambassador Kamalesh Sharma, Former Permanent Representative of India to the UN in Geneva and New York; and Former Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Timor-Leste (2002-2004) Introductory Remarks 10:15 am – 10:20 am Professor (Dr.) Vesselin Popovski, Professor & Vice Dean, Jindal Global Law School Executive Director, Centre for the Study of United Nations Keynote Address Meiji Revolution: What can India and Japan do for the Future of the United Nations? 10:20 am – 11:00 am Dr. Sukehiro -

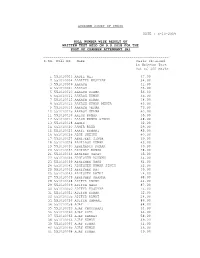

5-10-2019 Roll Number Wise Result of Written Test Held on 9.9.2018 for the Post of Chamber Atten

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA DATE : 5-10-2019 ROLL NUMBER WISE RESULT OF WRITTEN TEST HELD ON 9.9.2018 FOR THE POST OF CHAMBER ATTENDANT (R) ------------------------------------------------------------- S.No. Roll_No Name Marks obtained in Written Test out of 100 Marks ------------------------------------------------------------- 1 551010003 AADIL ALI 47.00 2 551010004 AADITYA KASHYAP 34.00 3 551010006 AAKASH 41.00 4 551010007 AAKASH 23.00 5 551010010 AAKASH KUAMR 56.00 6 551010011 AAKASH KUMAR 35.00 7 551010012 AAKASH KUMAR 38.00 8 551010013 AAKASH KUMAR MEHTA 43.00 9 551010014 AAKASH VERMA 73.00 10 551010015 AAKASH VERMA 40.00 11 551010016 AALOK KUMAR 35.00 12 551010017 AALOK KUMAR SINGH 48.00 13 551010018 AAMIR 32.00 14 551010020 AAMIR RAZA 29.00 15 551010023 AARTI KUMARI 85.00 16 551010026 ABHI SHEIKH 40.00 17 551010027 ABHIJEET SINGH 39.00 18 551010028 ABHILASH KUMAR 43.00 19 551010030 ABHIMANYU KUMAR 39.00 20 551010032 ABHINAY KUMAR 28.00 21 551010034 ABHINAY YADAV 35.00 22 551010036 ABHISHEK ACHWAN 34.00 23 551010039 ABHISHEK GARG 61.00 24 551010041 ABHISHEK KUMAR SINGH 32.00 25 551010042 ABHISHEK RAJ 39.00 26 551010043 ABHISHEK RATHI 74.00 27 551010045 ABHISHEK SHARMA 68.00 28 551010048 ADITYA ANAND 44.00 29 551010049 ADITYA GAUR 87.00 30 551010050 ADITYA KASHYAP 75.00 31 551010051 ADITYA KUMAR 32.00 32 551010055 ADITYA RAWAT 24.00 33 551010056 ADITYA SANWAL 86.00 34 551010058 AJAY 84.00 35 551010059 AJAY CHOUDHARY 34.00 36 551010060 AJAY GOEL 66.00 37 551010062 AJAY KANWAT 58.00 38 551010063 AJAY KUMAR 39.00 39 551010064 AJAY KUMAR -

NHRC Annual Report 2001-2002

National Human Rights Commission ANNUAL REPORT 2001-2002 Sardar Patel Bhawan w Sansad Marg, New Delhi 110001 Contents Preface 1 Introduction 2 Experience of the Working of the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993 8 3 Situation in Gujarat 20 Civil Liberties 24 A] Human Rights in Areas of Insurgency and Terrorism 24 B] Custodial Death, Rape and Torture 32 C] Encounter Deaths 34 D] Video Filming of Post-Mortem Examination and Revision of Autopsy Forms 35 E] Systemic Reforms: Police 36 F] Human Rights and Administration of Criminal Justice System 39 ANNUAL REPORT 2001-2002 II CONTENTS G] Custodial Institutions 40 1) Visits to Jails 40 2) Prison Population 42 3) Medical Examination of Prisoners on Admission to Jail 42 4) Mentally III Patients Languishing in Jails 43 5) Sensitisation of Jail Staff 43 6) Visits to Other Correctional Institutions/Protection Homes 45 H] Improvement of Forensic Science Laboratories 45 Review of Laws, Implementation of Treaties and Other International Instruments of Human Rights (Section 12(d), (f) and (j) of the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993) 48 A] Prevention of Terrorism Ordinance, 2001 48 B] Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1929 50 C] Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993 51 D] Implementation of Treaties and other International Instruments 52 1) Protocols to the Convention on the Rights of the Child 52 2) Protocols to the Geneva Convention 52 3) Convention Against Torture 53 4) Convention and Protocol on the Status of Refugees 53 E] Freedom of Information Bill, 2000 55 F] Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, -

Annual Report-2004-2005

122 Board of Trustees Shri Soli J. Sorabjee, President Dr Kapila Vatsyayan Prof. M.G.K. Menon Smt. Justice (Retd.) Leila Seth Dr L.M. Singhvi Dr R.K. Pachauri Dr Karan Singh Shri P.C. Sen, Director Director Shri P. C. Sen Executive Committee Shri P.C. Sen, Chairman Shri M.P. Wadhawan, Hon. Treasurer Smt. Rajni Kumar Shri Inder Malhotra Cmdre C. Uday Bhaskar Dr Arvind Pandalai Shri Vipin Malik Cmdre K.N. Venugopal, Secretary Dr S.M. Dewan Finance Committee Dr L.M. Singhvi Shri M.P. Wadhawan Shri Inder Malhotra Cmdre (Retd.) K.N. Venugopal Dr E.A.S. Sarma Shri P.R. Sivasubramanian Shri P.C. Sen Medical Consultants Dr K. P. Mathur Dr (Mrs.) Rita Mohan Dr K. A. Ramachandran Dr B. Chakravorty Dr Mohammad Qasim Senior Staff Cmdre (Retd.) K. N. Venugopal Secretary Shri L. K. Joshi Chief General Manager Shri P. R. Sivasubramanian Chief Finance Officer Dr H. K. Kaul Chief Librarian Dr Geeti Sen Chief Editor Dr A. C. Katoch Administration Officer Ms Premola Ghose Chief, Programme Division Shri Arun Potdar Chief, Maintenance Division Shri W. R. Sehgal Accounts Officer 120 2005-2006 THIS IS THE 45th Annual Report of the India International Centre for the year commencing the 1st of February 2005 to the 31st of January 2006. It will be placed before the 50th Annual General Body Meeting of the Centre, to be held on the 31st of March 2006. Elections to the Executive Committee and the Board of Trustees of the Centre for the two year period 2005-07 were initiated in the latter half of 2004. -

![29 November, 2005]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8927/29-november-2005-6458927.webp)

29 November, 2005]

RAJYA SABHA [29 November, 2005] REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENT RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON PERSONNEL, PUBLIC GRIEVANCES, LAW AND JUSTICE SHRI E.M. SUDARSANA NATCHIAPPAN (Tamil Nadu): Sir, I present the Thirteenth Report (in English and Hindi) of the Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice on the Prevention of Child Marriage Bill, 2004. MR. CHAIRMAN: Shri Arun Jaitley to move the motion. _________ MOTION Condemnation of alleged involvement of Indian entities and individuals as non-contractual beneficiaries of United Nations' Oil-for-Food-Programme in Iraq as reported by Volcker Committee SHRI ARUN JAITLEY (Gujarat): Mr. Chairman, Sir, let me first express my gratitude to you for permitting me to move this Motion under rule 167. The Motion I move reads: "That this House strongly condemns the alleged involvement of some Indian entities and individuals as non-contractual beneficiaries of the United Nations' Oil-for-Food-Programme in Iraq, as reported in the Report of the United Nations' Independent Inquiry Committee (Volcker Committee)." Sir, in the past few weeks, we have had from the Government at the highest level and from the political parties whose alliance and coalition is in power certain responses to what has been stated in the Independent Inquiry Committee's Report. Let us remember, and this needs to be underlined, that this Report is no ordinary document. This Report has not only domestic significance, as far as India is concerned, this Report is a document of high international credibility. And amongst others, this Report has mentioned, at least, two prominent Indian entities along with a third one, then, there are several other companies, and what has disturbed the country the most is a reference to a political party which has been in power in India for the longest duration of time as also a very hon. -

List of Rhodes Scholars - Wikipedia

1/7/2020 List of Rhodes Scholars - Wikipedia List of Rhodes Scholars This is a list of Rhodes Scholars, covering notable people who are Rhodes Scholarship recipients, sorted by year and surname. Key to the columns in the main table: Column Description of column contents label Name The name of the scholarship recipient. The university where the eligible studies were performed. Note that under the terms of University Rhodes' will, there are only fourteen regions which nominate candidates – see Rhodes Scholarship#Allocations. Oxford The Oxford College where the studies supported by the scholarship were performed. College Year The year in which the scholarship was awarded. Notability A brief summary (maximum two lines) of the recipient's notability. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Rhodes_Scholars 1/32 1/7/2020 List of Rhodes Scholars - Wikipedia Oxford Name University Year Notability College Historian of South Africa and critic William Miller Macmillan Stellenbosch Merton 1903 of colonial rule in Africa and the West Indies Lawyer and academic (University John Behan Melbourne Hertford 1904 and Trinity Colleges)[1] Forester who played First-class Norman Jolly Adelaide Balliol 1904 cricket for Worcestershire[2] U.S. Commissioner of Education John J. Tigert Vanderbilt Pembroke 1904 (1921–1928), president of the University of Florida (1928–1947)[3] New Zealand chemist, university Philip Robertson Victoria (NZ) Trinity 1905 professor and writer[4] The first Baron Robinson, regarded Roy Robinson Adelaide Magdalen 1905 as the chief architect of state forestry in Great Britain[5] German sociologist and Carl Brinkmann [a] Queen's 1904 economist[6] Historian at Boston University Warren Ault Baker Jesus 1907 1913–1957; Huntington Professor of History[7] New Clarence H.