U.S. V. Saldana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gang Project Brochure Pg 1 020712

Salt Lake Area Gang Project A Multi-Jurisdictional Gang Intelligence, Suppression, & Diversion Unit Publications: The Project has several brochures available free of charge. These publications Participating Agencies: cover a variety of topics such as graffiti, gang State Agencies: colors, club drugs, and advice for parents. Local Agencies: Utah Dept. of Human Services-- Current gang-related crime statistics and Cottonwood Heights PD Div. of Juvenile Justice Services historical trends in gang violence are also Draper City PD Utah Dept. of Corrections-- available. Granite School District PD Law Enforcement Bureau METRO Midvale City PD Utah Dept. of Public Safety-- GANG State Bureau of Investigation Annual Gang Conference: The Project Murray City PD UNIT Salt Lake County SO provides an annual conference open to service Salt Lake County DA Federal Agencies: providers, law enforcement personnel, and the SHOCAP Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, community. This two-day event, held in the South Salt Lake City PD Firearms, and Explosives spring, covers a variety of topics from Street Taylorsville PD United States Attorney’s Office Survival to Gang Prevention Programs for Unified PD United States Marshals Service Schools. Goals and Objectives commands a squad of detectives. The The Salt Lake Area Gang Project was detectives duties include: established to identify, control, and prevent Suppression and street enforcement criminal gang activity in the jurisdictions Follow-up work on gang-related cases covered by the Project and to provide Collecting intelligence through contacts intelligence data and investigative assistance to with gang members law enforcement agencies. The Project also Assisting local agencies with on-going provides youth with information about viable investigations alternatives to gang membership and educates Answering law-enforcement inquiries In an emergency, please dial 911. -

Private Conflict, Local Organizations, and Mobilizing Ethnic Violence In

Private Conflict, Local Organizations, and Mobilizing Ethnic Violence in Southern California Bradley E. Holland∗ Abstract Prominent research highlights links between group-level conflicts and low-intensity (i.e. non-militarized) ethnic violence. However, the processes driving this relationship are often less clear. Why do certain actors attempt to mobilize ethnic violence? How are those actors able to mobilize participation in ethnic violence? I argue that addressing these questions requires scholars to focus not only on group-level conflicts and tensions, but also private conflicts and local violent organizations. Private conflicts give certain members of ethnic groups incentives to mobilize violence against certain out-group adversaries. Institutions within local violent organizations allow them to mobilize participation in such violence. Promoting these selective forms of violence against out- group adversaries mobilizes indiscriminate forms of ethnic violence due to identification problems, efforts to deny adversaries access to resources, and spirals of retribution. I develop these arguments by tracing ethnic violence between blacks and Latinos in Southern California. In efforts to gain leverage in private conflicts, a group of Latino prisoners mobilized members of local street gangs to participate in selective violence against African American adversaries. In doing so, even indiscriminate forms of ethnic violence have become entangled in the private conflicts of members of local violent organizations. ∗Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, The Ohio State University, [email protected]. Thanks to Sarah Brooks, Jorge Dominguez, Jennifer Hochschild, Didi Kuo, Steven Levitsky, Chika Ogawa, Meg Rithmire, Annie Temple, and Bernardo Zacka for comments on earlier drafts. 1 Introduction On an evening in August 1992, the homes of two African American families in the Ramona Gardens housing projects, just east of downtown Los Angeles, were firebombed. -

Theories of Organized Criminal Behavior

LYMAMC02_0131730363.qxd 12/17/08 3:19 PM Page 59 2 THEORIES OF ORGANIZED CRIMINAL BEHAVIOR This chapter will enable you to: • Understand the fundamentals behind • Learn about social disorganization rational choice theory theories of crime • See how deterrence theory affects • Explain the enterprise theory crime and personal decisions to of organized crime commit crime • Learn how organized crime can be • Learn about theories of crime explained by organizational theory INTRODUCTION In 1993, Medellin cartel founder Pablo Escobar was gunned down by police on the rooftop of his hideout in Medellin, Colombia. At the time of his death, Escobar was thought to be worth an estimated $2 billion, which he purportedly earned during more than a decade of illicit cocaine trafficking. His wealth afforded him a luxurious mansion, expensive cars, and worldwide recognition as a cunning, calculating, and ruthless criminal mastermind. The rise of Escobar to power is like that of many other violent criminals before him. Indeed, as history has shown, major organized crime figures such as Meyer Lansky and Lucky Luciano, the El Rukinses, Jeff Fort, and Abimael Guzmán, leader of Peru’s notorious Shining Path, were all aggressive criminals who built large criminal enterprises during their lives. The existence of these criminals and many others like them poses many unanswered questions about the cause and development of criminal behavior. Why are some criminals but not others involved with organized crime? Is organ- ized crime a planned criminal phenomenon or a side effect of some other social problem, such as poverty or lack of education? As we seek answers to these questions, we are somewhat frustrated by the fact that little information is available to adequately explain the reasons for participating in organized crime. -

Gang Evidence: Issues for Criminal Defense Susan L

Santa Clara Law Review Volume 30 | Number 3 Article 3 1-1-1990 Gang Evidence: Issues for Criminal Defense Susan L. Burrell Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Susan L. Burrell, Gang Evidence: Issues for Criminal Defense, 30 Santa Clara L. Rev. 739 (1990). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol30/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GANG EVIDENCE: ISSUES FOR CRIMINAL DEFENSE Susan L. Burrell* It is my belief we don't know a helluva lot about gangs. I don't know what the hell to do about it as a matter of fact. Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl F. Gates' The label "gang-related" has far-reaching ramifications in criminal cases. Gang cases are singled out for investigation and prosecution by special units. At trial, gang affiliation may raise a host of evidentiary problems. At sentencing, evidence of gang membership is sure to affect the court's exercise of discretion. This article will explore the major issues that may arise when gang evidence is presented in a criminal or juve- nile case. The primary focus will be on street gangs, rather than organized crime or prison gangs. I. GANG CASES IN A SOCIETAL CONTEXT Representation of a gang member must begin with an understanding of what gangs are and how society has treated them. -

Y a Community Response Manual

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. / Y ./ A Community Response Manual f~ 0 Office for Victims American Probation and DVC of Crime ® Parole Association / I I~'-/o~1 ./ A Celebrity [Resp©~se/~a~a~ {C ) " @~'(~ Office for Victims American Probation and of Crime Parole Association Author Anne K. Seymour ISBN #0-87292-888-8 Copyright 2001 This document was prepared by the American Probation and Parole Association in cooperation with The Council of State Governments, under grant number 96-VF-GX-K001, awarded by the Office for Victims of Crime, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this document are those of the author and do not represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. The Office for Victims of Crime is a component of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Assistance, the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, and the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. L ............................... TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................... i SETTING THE STAGE FOR ADDRESSING VICTIM NEEDS AND ISSUES IN OFFENDER REENTRY .......................................................................................................... 1 Offender Reentry: A Victim's Perspective ................................................................................... -

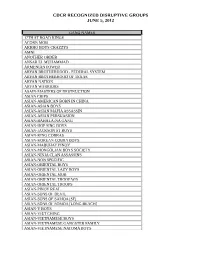

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

Glendale Police Department

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ClPY O!.F qL'J;9{'jJ.!JL[/E • Police 'Department 'Davit! J. tJ1iompson CfUt! of Police J.1s preparea 6y tfit. (jang Investigation Unit -. '. • 148396 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been g~Qted bY l' . Giend a e C1ty Po11ce Department • to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyright owner. • TABLEOFCON1ENTS • DEFINITION OF A GANG 1 OVERVIEW 1 JUVENILE PROBLEMS/GANGS 3 Summary 3 Ages 6 Location of Gangs 7 Weapons Used 7 What Ethnic Groups 7 Asian Gangs 8 Chinese Gangs 8 Filipino Gangs 10 Korean Gangs 1 1 Indochinese Gangs 12 Black Gangs 12 Hispanic Gangs 13 Prison Gang Influence 14 What do Gangs do 1 8 Graffiti 19 • Tattoo',;; 19 Monikers 20 Weapons 21 Officer's Safety 21 Vehicles 21 Attitudes 21 Gang Slang 22 Hand Signals 22 PROFILE 22 Appearance 22 Headgear 22 Watchcap 22 Sweatband 23 Hat 23 Shirts 23 PencHetons 23 Undershirt 23 T-Shirt 23 • Pants 23 ------- ------------------------ Khaki pants 23 Blue Jeans 23 .• ' Shoes 23 COMMON FILIPINO GANG DRESS 24 COMMON ARMENIAN GANG DRESS 25 COrvtMON BLACK GANG DRESS 26 COMMON mSPANIC GANG DRESS 27 ASIAN GANGS 28 Expansion of the Asian Community 28 Characteristics of Asian Gangs 28 Methods of Operations 29 Recruitment 30 Gang vs Gang 3 1 OVERVIEW OF ASIAN COMMUNITIES 3 1 Narrative of Asian Communities 3 1 Potential for Violence 32 • VIETNAMESE COMMUNITY 33 Background 33 Population 33 Jobs 34 Politics 34 Crimes 34 Hangouts 35 Mobility 35 Gang Identification 35 VIETNAMESE YOUTH GANGS 39 Tattoo 40 Vietnamese Background 40 Crimes 40 M.O. -

Mexican Mafia Timeline

MEXICAN MAFIA TIMELINE April 24, 1923 Henry "Hank" Leyva born in Tuscon, Arizona. April 10, 1929 Joe "Pegleg" Morgan born. 1935 1st generation "Originals" of Hoyo Maravilla gang forms. 1939 2nd generation "Cherries" of Hoyo Maravilla gang forms. December 1941 Henry "Hank" Leyva, Joe Valenzuela and Jack Melendez all members from 38th street gang in Long Beach arrested on suspicion of armed robbery. Charges dropped against Joe Valenzuela and Jack Melendez but Leyva is rebooked on a charge of assault with a deadly weapon. Leyva pled guilty and received a 3 month county jail term. August 2, 1942 Gang fight involving 38th street gang from Long Beach and a Downey gang results in the death of Jose Diaz. January 13, 1943 11 members of the 38th street gang are sentenced to prison for the murder of Jose Diaz. June 3, 1943 The Zoot suites erupt in Los Angeles. Many blame the racial tension in the city as a result of the treatment hispanics were subjected to while they searched for the killers of Jose Diaz. October 4, 1943 District Court of Appeals dismisses the case against the members of the 38th st., and orders them freed from custody. 1946 Joe Morgan [Maravilla gang] beats the husband of his 32 year old girlfriend to death and buries the body in a shallow grave. While awaiting trial he escapes using the identification papers of a fellow inmate awaiting transfer to a forestry camp. He is recaptured and sentenced to 9 years at San Quentin.. 1954 South Ontario Black Angels gang is formed. -

Gun Violence in the LAPD 77Th Street Area: Research Results and Policy Options

Gun Violence in the LAPD 77th Street Area Research Results and Policy Options GEORGE TITA, SCOTT HIROMOTO, JEREMY WILSON, JOHN CHRISTIAN, CLIFFORD GRAMMICH WR-128-OJP January 2004 Prepared for Office of Justice Programs Gun Violence in the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) 77th Street Area: Background Information and Policy Options Introduction This document is intended to aid the U.S. Attorney’s Office in designing and implementing a Project Safe Neighborhoods gun-violence reduction strategy in the 77th Street Area of the Los Angeles Police Department. (A future analysis, pending approved access to and analysis of homicide records, will focus on the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Century Station and its nearby areas.) We consider three topics: 1. Analysis of data on the 322 homicides, most of which were gang related, in the area from January 1998 through March 2003 2. Insights gathered from interviews with local experts, including police officers, probation officers, and community representatives, including their assessment of individual gangs in the area 3. A review of three potential interventions implemented elsewhere and the pros and cons of applying them to the 77th Street area Analysis of Homicide Data We chose to analyze homicide data to gauge violence in the area because no other type of crime gets more time and attention than homicide, and because homicide has been shown to be a good proxy for other types of violence, especially gun assaults. The difference between a homicide and an attempted homicide or an aggravated assault, for example, rarely depends on the intent of the offender but rather on the location of the wound and the speed of medical attention. -

Gangs-Overview-LES-FOUO.Pdf

2 Updated 10/2010 850,000 - Gang members in 31,000 gangs in the United States 300,000 - Gang members in over 2,000 gangs in California 150,000 - Gang members in over 1000 gangs in Los Angeles County 20,000 - Gang members in Orange County 10,000 - Gang members in San Diego County 1,000 - Gang members in Imperial County • Estimated Strengths Circ: 2008 • 97,000 LA County Gang Members • 6,700 Female Gang Members (6.7%) • 28,400 Black Gang Members • 58,800 Hispanic Gang Members • 3,500 Asian Gang Members • 311 Black Gangs (83 Blood) • 573 Hispanic Gangs • 104 Asian Gangs • 28 White Gangs • 18,000 LA Morgue Bodies Processed • 326 Gang Fatalities in 2009 • These numbers are based on actual identified members, not estimates (2009) A group of three or more persons who are united by a common ideology that revoles around criminal activity • Gangs are not part of one’s ethnic culture • Gangs are part of a criminal culture • The gang comes before religion, family, marriage, community, friendship and the law. “Barney” Mayberry Crips - Criminal Gangs: Members conspire or commit criminal acts for the benefit of the gang - Traditional Gangs: Common name or symbol and claim territory - Non-Traditional Gangs: Do not claim territory, but may have a location that members frequent • Taggers/Bombers • Party Crews • Rappers Young tagger in training • Gothics • Punks • Stoners • Car Clubs • SHARP Skin Heads • Occult Gangs Identity or Recognition - Allows a gang member to achieve a level or status he feels impossible outside the gang culture. They visualize themselves as warriors protecting their neighborhood. -

Drugs and Crime Gang Profile

LIMITED OFFICIAL USE – LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE Drugs and Crime Gang Profile Product No. 2002-M0465-001 NOVEMBER 2002 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE Crips The Crips, one of the largest and most violent associations of street gangs in the United States, is an association of structured and unstructured gangs that have adopted a common gang culture. Crips membership is estimated between 30,000 and 35,000; most members are African American men from the Los Angeles metropolitan area. Crips gangs are most active in the Southwest, Pacific, West Central, Southeast, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. Their main source of income is street-level distribution of powdered cocaine, crack cocaine, marijuana, and PCP. The gangs also are involved in many other types of criminal activity including assault, auto theft, burglary, carjacking, drive-by shooting, extortion, homicide, identification fraud, and robbery. Background Originally called the Avenue Cribs, the Crips Hardy, Bennie Simpson, Mack Thomas, and Angelo street gang was formed in Los Angeles, California, White, recruited more young men and increased the in the mid-1960s. Raymond Washington, a student gang’s involvement in violent criminal activity. The at Fremont High School in Los Angeles, founded original gang adopted the name Crips when a news- the gang as a political organization and later used it paper article published in the Los Angeles Sentinel in to provide protection from other gangs and to profit February 1972 referred to some Cribs members who from criminal activity. Washington organized the carried canes as “Crips” (for cripples). Cribs in imitation of the Black Panther Party and the Avenues, an older Los Angeles street gang. -

This Project Is Supported by Grant No. 2007-MU-BX-K003 Awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance

This project is supported by Grant No. 2007-MU-BX-K003 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and the Office for Victims of Crime. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This project is supported by Grant No. 2007-MU-BX-K003 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and the Office for Victims of Crime. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. 1 Mr. Jonathan Cristall is an assistant supervisor in the Los Angeles City Attorney’s Office. He supervises Project T.O.U.G.H. (Taking Out Urban Gang Headquarters)—a specialized and unique unit that works in close partnership with local and federal law enforcement agencies to target nuisance gang properties. Mr. Cristall has prosecuted and supervised gang abatements against gang members of the Avenues, MS-13, 18th Street, and numerous Crips and Bloods sets, to name a few. The prosecutions have resulted in the closure and subsequent demolition of numerous gang hangouts and headquarters, countless injunctions, and millions of dollars in monetary judgments against gang members and property owners.