The Hardest Working Slacker in the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marketing Lessons I Learned from Working with Kiss

MARKETING LESSONS I LEARNED FROM WORKING WITH KISS BY: MICHAEL BRANDVOLD Copyright 2011 Michael Brandvold Marketing • www.MichaelBrandvold.com "Quite eloquent. You're a powerful and attractive man." Gene Simmons Copyright 2011 Michael Brandvold Marketing • www.MichaelBrandvold.com CONTENTS • About • Acknowledgements • Testimonials • No Denying the Influence • All Press is Good Press • Love Me or Hate Me, Just Spell My Name Right • Wait for the Right Time • It’s All Branding • Everything You Do Will Not Succeed • Treat the Media with Respect • Listen to Your Fans You Work for Them • The Secret to Success is to Offend the Greatest Number of People • If You Don’t Ask For It You Won’t Get It • Separate Business and Pleasure • They Aren’t Afraid to Change Their Minds • The Takeaway • Contact Copyright 2011 Michael Brandvold Marketing • www.MichaelBrandvold.com ABOUT In both mainstream and adult entertainment, Michael Brandvold’s marketing talents, skills and savvy are vital assets that numerous companies rely upon to expand, prosper and operate effectively, efficiently and profitably in the online economy. Upon graduating from Mankato State University in 1987, Michael accepted the position of Director of Marketing with DKP Productions, an artist management firm in Chicago, before joining Red Light Records 1990, as National Radio Promotions manager. A self-taught master of HTML, Michael launched websites for Perris Records, Creative Communications, Sportmart, and Montgomery Ward. But it was KISS Otaku – his KISS fan site launched in 1995 – that would change his fortunes forever. In 1998, Gene Simmons of KISS discovered KISS Otaku and personally tapped Michael as the Director of Web Services at Signatures Network, a Sony/CMGi company, where he built-from-scratch, managed and grew KISSonline into a multi-million dollar enterprise with over of a half million visitors a month. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Kiss-Guitar-April-2016.Pdf

APRIL 1996 • VOLUME 13 • NO. 6 FEATURES 24 The Best Guitarists You've Never Heard Of We could name them here, but you've never heard of them. So read on 28 Kiss The rock circus rolls back into town 28 Riffology Classic riffs and solos, plus a Kiss history 42 Alive Again Little Deuce Scoop: Exclusive interviews with Ace, Gene and Bruce on the family reunion and future plans 48 Rhythm Displacement by Jon Finn Professor Finn gets funky 56 Studio Guitarists byWolfMarsha/1 Session great Steve Lukather takes us on a walk behind the glass PROFILE 21 Bert Jansch byHPNewquist COLUMNS 70 Mike Stern OVER THE TOP Bop 'n' Roll, Part 2 72 Alex Skolnick THE METAL EDGE 74 Reeves Gabrels BEYOND GUITAR 76 Tony Franklin BASS NOTES 78 Steve Morse OPEN EARS 152 HookinQ Up Your Pedals SOUND F/X 158 The Recording Guitarist Oat's What I ua About DAT DEPARTMENTS 6 Opening Act 8 Input 10 Groundwire 68 Contest WinaB.C. Rich guitar 69 Toy Box Knowyourtubetypes 156 Guitar Picks 164 Tracks 172 Advertiser Index ENCORE 176 Musical Definitions by Charles H. Chapman and Jon Chappell GUITAR & BASS SHEET MUSIC 81 Performance Notes by Jon Chappell 82 Explaining Tab 83 MY JEKYLL DOESN'T HIDE Ozzy Osbourne 95 BETH Kiss 105 AFTERSHOCK Van Halen 129 SATELLITE Dave Matthews Band 140 INTO THE GREAT WIDE OPEN Tom Petty ssues ofyo rou decide t :again. easure to se Malmsteen th this yea as speechles e to feel tha IG nally realize vrite for thos n [Riffolog ative bits an It's about tim ndwagon. -

Day Two LOTS 1446-1521 Page15 I446 GENE

'- I Day Two LOTS 1446-1521 Page 15 ~446 GENE SIMMONS Script of ELDER 1980 $488.75 1447 GENE SIMMONS KISS Press Kit from ELDER Album, 1981 $373.75 1448 KISS Costume Armbands GENE SIMMONS from ELDER Era, 1981 $460.00 1449 Costume GENE SIMMONS RDER I CREATUES OF NIGHTTour 1981-1983 $4600.00 1450 KISS Costume PAULSTANLEY ELDER Tour, 1981 $5 175.00 j452 KISS Belt PAUL STANLEY ELDER Era, 1981 $1 380.00 1453 Bodysuit ACE FREHLEY ELDER 1CREATURES OF NIGHTTour 11981·1983 $4312.50 ~454 KISS Costume ERIC CARR from ELDER Era. 1981 $2875.00 ~460 KISS Top GENESIMMONS ASYLUM Tour, 1985-1986 $632.50 1461 KISS Costume Coat GENE SIMMONS ASYLUM Tour, 1985-1986 $1 265.00 i1469KISS Costume Jacket PAUL STANLEY ASYLUM Tour, 1985-1986 $3.737.50 ~472 KISS Costume Pants PAUL STANLEY ASYLUM Tour, 1985-1986 $1 ,725.001 1482 KISS Poster DesiQnlayout , 1984 $46000., . :. ~'. ~ ~483 KISS Band Portrait from ANIMALIZE Era, 1984 $345.00 ~484 KISS Costume Shin Guards GENE SIMMONS ANIMALIZE Tour, 1984-1986 $747.50 ~485 KISS Vest GENE SIMMONS ANIMALlZE Tour, 1984-1985 $2.070.00 ;1489PAUL STANLEY KISS Guitar ANIMALlZE Tour. 1984-1985 $4.887.50 h490 KISS Right Case and Drum Accessories ERIC CARR ANIMALIZE Tour. 1984 $488.75 ~492 KISS Vest BRUCE KUUCKfrom ANIMALlZETour, 1984-1985 $1.265.00 11495KISS Backstage Access Only Sign, 1999 $488.75 h496 Advertisement Proof, 1999 $977.50 11499GENE SIMMONS Simmons Records Mini Guitar Display, 1989 $431.25 1501 GENE SIMMONS Certification Document, 1984 $402.50 h502 Tour Book Cover Artwork for 10th ANNIVERSARY Tour, Circa 1982-1983 $258.75 • i1503 KISS Platinum Express Card. -

Eric Singer: Road Warrior

EXCLUSIVE! KISS DRUMMERS TIMELINE KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSTHE WORLD’SKISS KISS #1 DRUMKISS RESOURCEKISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS ERICKISS KISS KISSSINGER: KISS KISS KISS ROADKISS KISS KISS WARRIOR KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS2020 KISS KISSMD KISS READERS KISS KISS KISS KISSPOLL KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSSS KISSKIS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSSS KISSKIS KISS KISS KISSBALLOT’S KISS KISS KISS KISSOPEN! KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSSS KISS KIS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSREMO KISS SUBKISS MUFF’LKISS KISS REVIEWED KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSJANUARY KISS 2020 KISS KISS2019 KISS CHICAGO KISS KISS DRUM KISS KISS SHOW KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSCREATIVE KISS KISS PRACTICE KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSSTANTON KISS KISS MOORE KISS KISS GEARS KISS UPKISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS What’s Old is New Again. -

9.11.17 Press Release Gene Simmons & Ace Frehley

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact // Gates Lindquist [email protected] // 612.246.7250 Gene Simmons & Ace Frehley Will Perform Together For The First Time in Sixteen Years For ‘The Children Matter’ Benefit Concert For Hurricane Victims with special guests Don Felder & Cheap Trick St. Paul, MN | September 20th, 2017 www.thechildrenmatter.ngo September 11th, 2017 (Minneapolis, MN) – Today, Gene Simmons (KISS Co-founder, bassist) and Ace Frehley (original lead guitarist of KISS) announced they will perform together on-stage, the first-time in over 16 years (since Frehley left KISS in 2001) at The Children Matter Benefit Concert to support the victims of Hurricane Harvey. Don Felder (former lead guitarist of The Eagles) and Cheap Trick are confirmed to perform, with headliner Gene Simmons Band (which Frehley and Felder will be sitting in with) at The Children Matter Benefit Concert on September 20th 2017 in St. Paul, Minnesota. Over 10,000 expected to fill CHS Field Stadium in downtown St. Paul to witness rock history with once-in-a-lifetime collaborative performances between rock legends Gene Simmons, Ace Frehley, Don Felder and Cheap Trick as they turn up the volume for the victims of Hurricane Harvey. ALL proceeds from The Children Matter Benefit Concert will be directed to the hurricane relief efforts of the nonprofit MATTER. The nonprofit works in partnership with on-ground relief organizations to source and ship the items needed most, such as: MATTERbox Meal Kits, sanitation and contamination prevention supplies and more to the children and families affected displaced by the hurricane. Tickets starting under $60 and range up to $250 for VIP Meet & Greet. -

Paul Stanley and About KISS

Edition : July 12, 2019 Paul Stanley And About KISS this book talks about the KISS Band Author of the magazine: Nelia Starchild All rights reserved - Standard copyright license Nelia Starchild appeared under the title : Paul Stanley et le groupe KISS ISBN : 978-1-71699-778-5 SOMMAIRE : Biography of Paul Stanley: Page 1 and 2 KISS their success in the 80s: Years Culte of KISS: Page 4 The albums of the success of KISS: Page 5 and 6 The Hits of the Popular 2000s: Page 6 Paul Stanley: Page 7 Detroit Rock City: Page 7 Scooby-Doo! And KISS: Rock and Roll Mystery Page 8 End Of The Road Tour: 9 and 10 KISS: Alive! Page 11 KISS: Alive II Page 12 KISS: Alive III Page 13 KISS: Meets the Phantom of the Park: Page 14, 15, 16 BIOGRAPHY KISS BAND: 17 Paul Stanley Alias: Stanley Bert Eisen is an American singer and musician, born January 20, 1952, in Queens, Manhattan, New York he's known worldwide for being Starchild the frontman from the KISS singers group and the rhythm guitarist of the hard rock band KISS since he founded the group in 1973. Private life: Paul Stanley to marry his first wife actress Pamela Bowen in 2001, filed for divorce after nine years of marriage. They have a son, Evan Shane Stanley born June 6, 1994. On November 19, 2005, Paul Stanley married his longtime girlfriend Erin Sutton at the Ritz-Carlton in Pasadena, California. They had their first child, Colin Michael Stanley on September 6, 2006. The couple had their second child, Sarah Brianna, on January 28, 2009 in Los Angeles. -

ANSAMBL ( [email protected] ) Umelec

ANSAMBL (http://ansambl1.szm.sk; [email protected] ) Umelec Názov veľkosť v MB Kód Por.č. BETTER THAN EZRA Greatest Hits (2005) 42 OGG 841 CURTIS MAYFIELD Move On Up_The Gentleman Of Soul (2005) 32 OGG 841 DISHWALLA Dishwalla (2005) 32 OGG 841 K YOUNG Learn How To Love (2005) 36 WMA 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Dance Charts 3 (2005) 38 OGG 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Das Beste Aus 25 Jahren Popmusik (2CD 2005) 121 VBR 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS For DJs Only 2005 (2CD 2005) 178 CBR 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Grammy Nominees 2005 (2005) 38 WMA 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Playboy - The Mansion (2005) 74 CBR 841 VANILLA NINJA Blue Tattoo (2005) 76 VBR 841 WILL PRESTON It's My Will (2005) 29 OGG 841 BECK Guero (2005) 36 OGG 840 FELIX DA HOUSECAT Ft Devin Drazzle-The Neon Fever (2005) 46 CBR 840 LIFEHOUSE Lifehouse (2005) 31 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS 80s Collection Vol. 3 (2005) 36 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Ice Princess OST (2005) 57 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Lollihits_Fruhlings Spass! (2005) 45 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Nordkraft OST (2005) 94 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Play House Vol. 8 (2CD 2005) 186 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS RTL2 Pres. Party Power Charts Vol.1 (2CD 2005) 163 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Essential R&B Spring 2005 (2CD 2005) 158 VBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS Remixland 2005 (2CD 2005) 205 CBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS RTL2 Praesentiert X-Trance Vol.1 (2CD 2005) 189 VBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS Trance 2005 Vol. 2 (2CD 2005) 159 VBR 839 HAGGARD Eppur Si Muove (2004) 46 CBR 838 MOONSORROW Kivenkantaja (2003) 74 CBR 838 OST John Ottman - Hide And Seek (2005) 23 OGG 838 TEMNOJAR Echo of Hyperborea (2003) 29 CBR 838 THE BRAVERY The Bravery (2005) 45 VBR 838 THRUDVANGAR Ahnenthron (2004) 62 VBR 838 VARIOUS ARTISTS 70's-80's Dance Collection (2005) 49 OGG 838 VARIOUS ARTISTS Future Trance Vol. -

Student Dies at IU Natatorium Douglas Had Been at the Pool with His Girl Tate Douglas Through Two-Nun CPR

Take me out to ... Shaken, not stirred Nomadic Metros find a IndianajxJi> is cauhinjj p**e bomeaway from home 1 In Voice 1 In Perspectives on to the nationwide ^ in the friendly confines o( cultural craze of the Indianapolis’ Victory Field. Society shuns gays n . Seeing stars Page martini and citfar bar. JL*.J Wriler believes (he incredible amount of attention f " " Seasonal roster of entertainment at Deer Creek Monday — Apm 28.1997 the Ellen DeGeneres affair has attracted is a result Music Center offers a plethora of shows and Single Copy Free — 1 Section VW. 20. No. 31 O 1997 Th* Sagamore ofJudeoChristian societal prejudices against gays. festivals guaranteed to satisfy fans of all genres. 9 AcMrtiUMg miorm<X'Ofv <317\ 274 .3456 Student dies at IU Natatorium Douglas had been at the pool with his girl tate Douglas through two-nun CPR. Douglas at the scene “for a long amount of The Marion County Coroner s office has ■ Pblke, coroner continue friend Monica Jackson, also an IUPUI stu Members of Indianapolis Fur Department time bdofteJie was transported.” McKinney not yet determined the exact cause of lKm investigating April 20 death dent. Jackson had been in the bleachers near Rescue Squad 13 were the first to arrive on said glas’ death the area of the pool and screamed for a life the scene — roughly five minutes after Dou Shortly after arriving at Wishurd Memorial “He was reportedly pulled from tin* bottom of 18-year-old IUPUI freshman. guard when she realized Douglas had not re glas had been pulled from the water, accord Hospital s trauma unit, and less than an hour of the pool and a fair amount ot fluid tame surfaced. -

UWS Academic Portal the Rock Band KISS and American Dream

UWS Academic Portal The Rock Band KISS and American Dream Ideology James, Kieran; Briggs, Susan P.; Grant, Bligh Published in: European Journal of American Culture DOI: 10.1386/ejac.37.1.19_1 Published: 01/03/2018 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication on the UWS Academic Portal Citation for published version (APA): James, K., Briggs, S. P., & Grant, B. (2018). The Rock Band KISS and American Dream Ideology. European Journal of American Culture, 37(1), 19-37. https://doi.org/10.1386/ejac.37.1.19_1 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UWS Academic Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 17 Sep 2019 “The Rock Band KISS and American Dream Ideology” by Kieran James* University of the West of Scotland [email protected] Susan P. Briggs University of South Australia [email protected] and Bligh Grant University Technology Sydney [email protected] *Address for Correspondence: Dr Kieran James, School of Business and Enterprise, University of the West of Scotland, Paisley campus, Paisley, Renfrewshire, PA12BE, Scotland, tel: +44 (0)141 848 3350, e-mail: [email protected] and [email protected] Acknowledgements We thank Frances Miley, Andrew Read, conference participants at the International Conference for Critical Accounting (ICCA), Baruch College, New York City, 28 April 2011, this journal’s two anonymous reviewers, and this journal’s Editor for helpful comments. -

Dokken the Very Best of Dokken Mp3, Flac, Wma

Dokken The Very Best Of Dokken mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: The Very Best Of Dokken Country: Canada Released: 1999 Style: Hard Rock, Heavy Metal MP3 version RAR size: 1113 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1722 mb WMA version RAR size: 1834 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 648 Other Formats: RA AIFF MOD AA AHX MPC TTA Tracklist Hide Credits Breaking The Chains 1 –Dokken 3:52 Bass, Vocals – Juan CroucierWritten-By – Don Dokken, George Lynch Paris Is Burning (Live In Europe, 1982) 2 –Dokken 5:09 Bass, Vocals – Juan CroucierWritten-By – Don Dokken, George Lynch Into The Fire 3 –Dokken 4:27 Written-By – Don Dokken, George Lynch, Jeff Pilson Just Got Lucky 4 –Dokken 4:36 Written-By – George Lynch, Jeff Pilson Alone Again 5 –Dokken 4:22 Written-By – Don Dokken, Jeff Pilson Tooth And Nail 6 –Dokken 3:42 Written-By – George Lynch, Jeff Pilson, Mick Brown The Hunter 7 –Dokken 4:08 Written-By – Don Dokken, George Lynch, Jeff Pilson, Mick Brown In My Dreams 8 –Dokken 4:20 Written-By – Don Dokken, George Lynch, Jeff Pilson, Mick Brown It's Not Love 9 –Dokken 5:00 Written-By – Don Dokken, George Lynch, Jeff Pilson, Mick Brown Dream Warriors 10 –Dokken 4:48 Written-By – George Lynch, Jeff Pilson Burning Like A Flame 11 –Dokken 4:46 Written-By – Don Dokken, George Lynch, Jeff Pilson, Mick Brown Heaven Sent 12 –Dokken 4:53 Written-By – Don Dokken, George Lynch, Jeff Pilson Mr. Scary 13 –Dokken 4:30 Written-By – George Lynch, Jeff Pilson Walk Away 14 –Dokken 5:02 Producer – Angelo ArcuriWritten-By – Don Dokken, George Lynch, Jeff Pilson Mirror -

JROCK Houston - [email protected]

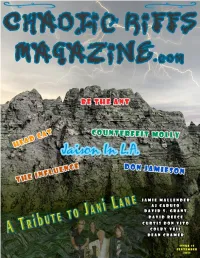

Magazine Staf Credits Interviews JROCK Houston - [email protected] KATZ – [email protected] Graphics: Leith Taylor - [email protected] Text Editor: Leith Taylor Copyright 2011. Chaotic Rifs Magazine September 2011 - Issue 19 2 Warrant’s Jani Lane Tribute …….6 Phil Soussan……8 WARRANT DRUMMER James Kottak……10 Counterfeit Molly……19 The Influence……20 Be The Ant……22 Live Wire – David Grant……24 Head Cat……28 Wings In Motion CD Review……33 Don Jamieson……34 Jaison In LA……40 Copyright 2011. Chaotic Rifs Magazine September 2011 - Issue 19 3 Talkback By JRock Houston Jani Lane is just the latest of many Rockers to leave the world way too young. I thought in light of this that this month's TALKBACK SECTON would take a look back at some other Rockers who checked out way too young. Let's take a trip down memory lane: 12/1/93 - Singer: Ray Gillian dies from Aids related complications. While he never appeared on record with Black Sabbath he was briefly a member of Black Sabbath's touring band when he briefly replaced legendary Singer: Glenn Hughes in the band. Following his gig with Sabbath Gillen briefly worked w/Ex Thin Lizzy/Whitesnake Guitarist: John Sykes in Blue Murder but eventually Gillen left Blue Murder and formed BadLands w/Ex Ozzy Osbourne/Ratt Guitarist: Jake E. Lee. Badlands released two albums before Gillen decided to leave because of friction that developed between Lee and Gillen. After Ray Gillen's death BADLANDS released a 3rd and final album called DUSK which was an album's worth of material of unreleased studio outakes.