Humour and Incongruity JOHN LIPPITT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stanislaw Piatkiewicz and the Beginnings of Mathematical Logic in Poland

HISTORIA MATHEMATICA 23 (1996), 68±73 ARTICLE NO. 0005 Stanisøaw PiaËtkiewicz and the Beginnings of Mathematical Logic in Poland TADEUSZ BATO G AND ROMAN MURAWSKI View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, Adam Mickiewicz University, ul. Matejki 48/49, 60-769 PoznanÂ, Poland provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector This paper presents information on the life and work of Stanisøaw PiaËtkiewicz (1849±?). His Algebra w logice (Algebra in Logic) of 1888 contains an exposition of the algebra of logic and its use in representing syllogisms. This was the ®rst original Polish publication on symbolic logic. It appeared 20 years before analogous works by èukasiewicz and Stamm. 1996 Academic Press, Inc. In dem Aufsatz werden Informationen zu Leben und Werk von Stanisøaw PiaËtkiewicz (1849±?) gegeben. Sein Algebra w logice (Algebra in der Logik) von 1888 enthaÈlt eine Darstel- lung der Algebra der Logik und ihre Anwendung auf die Syllogistik. PiaËtkiewicz' Schrift war die erste polnische Publikation uÈ ber symbolische Logik. Sie erschien 20 Jahre vor aÈhnlichen Arbeiten von èukasiewicz und Stamm. 1996 Academic Press, Inc. W pracy przedstawiono osobeË i dzieøo Stanisøawa PiaËtkiewicza (1849±?). W szczego lnosÂci analizuje sieË jego rozpraweË Algebra w logice z roku 1888, w kto rej zajmowaø sieË on nowymi no wczas ideami algebry logiki oraz ich zastosowaniami do sylogistyki. Praca ta jest pierwszaË oryginalnaË polskaË publikacjaË z zakresu logiki symbolicznej. Ukazaøa sieË 20 lat przed analog- icznymi pracami èukasiewicza i Stamma. 1996 Academic Press, Inc. MSC 1991 subject classi®cations: 03-03, 01A55. -

Laughter: the Best Medicine?

Laughter: The Best Medicine? by Barbara Butler elcome to a crash COLI~SCin c~onsecli1~11cc.~ol'nvgarivc emotions. Third, Oregon Institute ofMarine Biology Gelotology 101. That isn't a using Iiumor as :I c~ol)irigs(r:itcgy n~ayalso University of Oregon typo, Gelotology (from the I~enefithealth inclirec.tly I)y moderating ad- Greek root gelos (to laugh)), is a term verse effects of stress. Finally, humor may coined in 1964 by Dr. Edith Trager and Dr. provide another indirect Ixnefit to health W.F. Fry to describe the scientific study of by increasing one's level of social support laughter. While you still can't locate this (Martin, 2002, 2004). term in the OED, you can find it on the Web. The study of humor is a science, The physiology of humor and laughter researchers publish in the Dr. William F. Fry from Stanford University psychological and physiological literature has published a number of studies of the as well as subject specific journals (e.g., physiological processes that occur dur- Humor: International Journal of Humor ing laughter and is often cited by people Research). claiming that laughter is equivalent to ex- While at the Special Libraries As- ercise. Dr. Fry states, "I believe that we do sociation annual conference last June, I not laugh merely with our lungs, or chest was able to attend a session by Elaine M. muscles, or diaphragm, or as a result of a Lundberg called Laugh For the Health of stimulation of our cardiovascular activity. It. The room was packed and she had the I believe that we laugh with our whole audience laughing and learning for the physical being. -

Humour in Nietzsche's Style

Received: 15 May 2020 Accepted: 25 July 2020 DOI: 10.1111/ejop.12585 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Humour in Nietzsche's style Charles Boddicker University of Southampton, Southampton, UK Abstract Correspondence Nietzsche's writing style is designed to elicit affective Charles Boddicker, University of responses in his readers. Humour is one of the most common Southampton, Avenue Campus, Highfield Road, Southampton SO17 1BF, UK. means by which he attempts to engage his readers' affects. In Email: [email protected] this article, I explain how and why Nietzsche uses humour to achieve his philosophical ends. The article has three parts. In part 1, I reject interpretations of Nietzsche's humour on which he engages in self-parody in order to mitigate the charge of decadence or dogmatism by undermining his own philosophi- cal authority. In part 2, I look at how Nietzsche uses humour and laughter as a critical tool in his polemic against traditional morality. I argue that one important way in which Nietzsche uses humour is as a vehicle for enhancing the effectiveness of his ad hominem arguments. In part 3, I show how Nietzsche exploits humour's social dimension in order to find and culti- vate what he sees as the right kinds of readers for his works. Nietzsche is a unique figure in Western philosophy for the importance he places on laughter and humour. He is also unique for his affectively charged style, a style frequently designed to make the reader laugh. In this article, I am pri- marily concerned with the way in which Nietzsche uses humour, but I will inevitably discuss some of his more theo- retical remarks on the topic, as these cannot be neatly separated. -

Humour and Caricature Teachers Notes Humour and Caricature

Humour and Caricature Teachers Notes Humour and Caricature “We all love a good political cartoon. Whether we agree with the underlying sentiment or not, the biting wit and the sharp insight of a well-crafted caricature and its punch line are always deeply satisfying.” Peter Greste, Australian Journalist, Behind the Lines 2015 Foreward POINTS FOR DISCUSSION: Consider the meaning of the phrases “biting wit”, “sharp insight”, “well-crafted caricature”. Look up definitions if required. Do you agree with Peter Greste that people find political cartoons “deeply satisfying” even if they don’t agree with the cartoons underlying sentiment? Why/why not? 2 Humour and Caricature What’s so funny? Humour is an important part of most political cartoons. It’s a very effective way for The joke cartoonists to communicate their message to their audience can be simple or — and thereby help shape public opinion. multi-layered and complex. POINTS FOR DISCUSSION: “By distilling political arguments and criticisms into Do a quick exercise with your classmates — share a couple clear, easily digestible (and at times grossly caricatured) of jokes. Does everyone understand them? Why/why not? statements, they have oiled our political debate and What does this tell us about humour? helped shape public opinion”. Peter Greste, Australian Journalist, Behind the Lines foreward, http://behindthelines.moadoph.gov.au/2015/foreword. Why do you believe it’s important for cartoonists to make their cartoons easy to understand? What are some limitations readers could encounter which may hinder their understanding of the overall message? 3 Humour and Caricature Types of humour Cartoonists use different kinds of humour to communicate their message — the most common are irony, satire and sarcasm. -

On Laughter Supervisor: Rebekah Humphreys Word Count: 21991

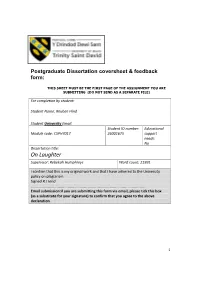

Postgraduate Dissertation coversheet & feedback form: THIS SHEET MUST BE THE FIRST PAGE OF THE ASSIGNMENT YOU ARE SUBMITTING (DO NOT SEND AS A SEPARATE FILE) For completion by student: Student Name: Reuben Hind Student University Email: Student ID number: Educational Module code: CSPH7017 26001675 support needs: No Dissertation title: On Laughter Supervisor: Rebekah Humphreys Word count: 21991 I confirm that this is my original work and that I have adhered to the University policy on plagiarism. Signed R J Hind …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Email submission:if you are submitting this form via email, please tick this box (as a substitute for your signature) to confirm that you agree to the above declaration. 1 ABSTRACT. Much of Western Philosophy has overlooked the central importance which human beings attribute to the Aesthetic experiences. The phenomena of laughter and comedy have largely been passed over as “too subjective” or highly emotive and therefore resistant to philosophical analysis, because they do not easily lend themselves to the imposition of Absolutist or strongly theory-driven perspectives. The existence of the phenomena of laughter and comedy are highly valued because they are viewed as strongly communal activities and expressions. These actually facilitate our experiences as inherently social beings, and our philosophical understanding of ourselves as beings, who experience passions and life itself amidst a world of fluctuating meanings and human drives. I will illustrate how the study of “Aesthetics” developed from Ancient Greek conceptions, through the post-Kantian and post-Romantic periods, which opened-up a pathway to the explicit consideration of the phenomena of laughter and comedy, with particular reference to the Apollonian/Dionysian conceptual schemata referred to in Nietzsche’s early works. -

An Introduction to Late British Associationism and Its Context This Is a Story About Philosophy. Or About Science

Chapter 1: An Introduction to Late British Associationism and Its Context This is a story about philosophy. Or about science. Or about philosophy transforming into science. Or about science and philosophy, and how they are related. Or were, in a particular time and place. At least, that is the general area that the following narrative will explore, I hope with sufficient subtlety. The matter is rendered non-transparent by the fact that that the conclusions one draws with regard to such questions are, in part, matters of discretionary perspective – as I will try to demonstrate. My specific historical focus will be on the propagation of a complex intellectual tradition concerned with human sensation, perception, and mental function in early nineteenth century Britain. Not only philosophical opinion, but all aspects of British intellectual – and practical – life, were in the process of significant transformation during this time. This cultural flux further confuses recovery of the situated significance of the intellectual tradition I am investigating. The study of the mind not only was influenced by a set of broad social shifts, but it also participated in them fully as both stimulus to and recipient of changing conditions. One indication of this is simply the variety of terms used to identify the ‘philosophy of mind’ as an intellectual enterprise in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.1 But the issue goes far deeper into the fluid constitutive features of the enterprise - including associated conceptual systems, methods, intentions of practitioners, and institutional affiliations. In order to understand philosophy of mind in its time, we must put all these factors into play. -

Humour and the Young Child

RESEARCH 4 19/2006/E Catherine Lyon Humour and the young child A review of the research literature What exactly is a sense of humour? Finally, does having a sense of hu- vision of a socially acceptable means On the basis of relevant research mour matter? Do children with a of expressing hostility and softening results on children and adults, ma- sense of humour have more friends, of an assertive/dominating style of ny favourable aspects of humour do better in school, or enjoy better interaction (McGhee, 1988). He states are presented. We learn that hu- emotional and physical health or not? rather unequivocally, “It is concluded mour is a skill that can be trained, Is a sense of humour inborn or some- that development of heightened early and this is where the use of media thing we can encourage? If we can humor helps to optimize children’s in the development of children’s teach a sense of humour, how do we social development.” humour comes into play. do that? Humour is frequently used to dispel Unlike other psychological constructs anxiety; by secondary reinforcement, (e. g., intelligence or extraversion) humour becomes a learned motive to there is no standard conception of experience mastery in the face of 1. What the research tells us sense of humour upon which re- anxiety – the “whistling in the dark” searchers generally agree (Martin, phenomenon. In studies investigating about humour and its 1998). With the caveat that this field stress and a sense of humour, e. g. development is currently made up of multiple ap- Martin and Lefcourt (1983 – cit. -

DOCTORAL THESIS Stories of Comedy and Tragedy in Therapy

DOCTORAL THESIS Stories of comedy and tragedy in therapy psychological therapists' experiences of humour in sessions with clients diagnosed with a terminal illness Chauhan, Gauri Award date: 2016 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 03. Oct. 2021 STORIES OF COMEDY AND TRAGEDY IN THERAPY: PSYCHOLOGICAL THERAPISTS’ EXPERIENCES OF HUMOUR IN SESSIONS WITH CLIENTS DIAGNOSED WITH A TERMINAL ILLNESS by Gauri Chauhan BSc A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PsychD Department of Psychology Roehampton University 2015 Abstract This research explores psychological therapists’ experiences of humour in sessions with clients diagnosed with a terminal illness. In considering the extensive research uncovered involving humour and death, comparatively -

Humour and Fate in Tom Stoppard's Play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead

Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Sayı 25/1,2016, Sayfa 74-86 HUMOUR AND FATE IN TOM STOPPARD’S PLAY ROSENCRANTZ AND GUILDENSTERN ARE DEAD Ayça ÜLKER ERKAN∗ Abstract The purpose of this study is to discuss physical humour arising from the characters’ quest for identity and to depict how the themes of death/ chance/ fate/ reality/ illusion function in the existentialist world of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Humour plays a significant role in the analysis of this tragicomedy. The theatre of the Absurd expresses the senselessness of the human condition, abandons the use of rational devices, reflects man’s tragic sense of loss, and registers the ultimate realities of the human condition, such as the problems of life and death. Thus the audience is confronted with a picture of disintegration. This dissolved reality is discharged through ‘liberating’ laughter which depicts the absurdity of the universe. Stoppard uses verbal wit, humour and farce to turn the most serious subjects into comedy. Humour is created by Guildenstern’s little monologues that touch on the profound but founder on the absurd. The play has varieties of irony, innuendo, confusion, odd events, and straight-up jokes. Stoppard’s use of the ‘play in play’ technique reveals the ultimate fate of the tragicomic characters Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. They confront the mirror image of their future deaths in the metadramatic spectacle performed by the Players. As such, the term “Stoppardian” springs out of his use of style: wit and comedy while addressing philosophical concepts and ideas. Key Words: The theatre of the Absurd, Humour, Identity confusion, Fate, The theme of death, Wit and comedy. -

Exploring Canarian Humour in the First Locally Produced Sitcom in RTVC

http://dx.doi.org/10.7592/EJHR2013.1.4.gonzalezcruz European Journal of Humour Research 1(4) 35 -57 www.europeanjournalofhumour.org Exploring Canarian humour in the first locally produced sitcom in RTVC Mª Isabel González Cruz Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria Abstract Between December 2011 and May 2012, the public television channel (RTVC) in the Canary Islands (Spain) aired, in prime time, the first locally produced situation comedy. Titled La Revoltosa (henceforth LR), it was the most ambitious production in the channel’s more than 14 years of existence. This series was said to display a humorous interpretation of Canarian society. Indeed, according to the executive producer, the characters reflected ordinary Canarian families. One of the attractions of the series was the inclusion of popular Canarian comedian Manolo Vieira as the main protagonist. In this paper, I briefly outline the strategies typically used by this important figure of Canarian humour before I discuss two episodes of LR to explore the resources they employ to provoke humour. Particularly, I study the role played by language, and analyse how characters and situations are portrayed, thus examining universal humour in contrast to regional or ethnic humour. This comparison between the humour strategies used by Manolo Vieira and the ones employed in LR will enable us to determine to what extent this sitcom favours the Canarian (ethnic) humour traditionally represented by Vieira or rather resorts to more general (universal) humour strategies and stereotypes. Keywords: Canarian humour; sitcoms; linguistic humour; stereotypes; Canarian Spanish. 1. Introduction It is widely recognised that humour has a high profile in our contemporary society. -

Liminal Laughter: a Feminist Vision of the Body in Resistance Sarah E

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Liminal Laughter: A Feminist Vision of the Body in Resistance Sarah E. Fryett Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES LIMINAL LAUGHTER: A FEMINIST VISION OF THE BODY IN RESISTANCE By SARAH E. FRYETT A Dissertation submitted to the Program of Interdisciplinary Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Sarah E. Fryett defended on March 18, 2010. __________________________ Robin T. Goodman Professor Directing Dissertation ___________________________ Marie Fleming University Representative ___________________________ Enrique Alvarez Committee Member ____________________________ Donna M. Nudd Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ John Kelsay, Chair, Program of Interdisciplinary Humanities ___________________________________ Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii Maricarmen Martinez In Solidarity iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation, though including the word “laughter” in the title, rarely induced me into peals of laughter, unless tinged by a certain manic madness. I am, however, greatly indebted to those individuals who kept me laughing and forced the madness to stay at bay. I take this opportunity to extend thanks to them. I would first like to thank my committee members: Robin Goodman, Marie Fleming, Enrique Alvarez, and Donna M. Nudd. Each provided me with their own unique resources. I thank Donna M. Nudd for taking the time to locate old Mickee Faust scripts and answer last minute frantic emails. -

Humor As Cognitive Play

Abstracts 393 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 JOHN MORREALL 27 28 Humor as Cognitive Play 29 30 31 This article assesses three traditional theories of laughter and humor: the Superi- 32 ority Theory, the Relief Theory, and the Incongruity Theory. Then, taking insights 33 from those theories, it presents a new theory in which humor is play with cognitive 34 shifts. 35 The oldest account of what we now call humor is the Superiority Theory. For 36 Plato and Aristotle laughter is an emotion involving scorn for people thought of as 37 inferior. Plato also objects that laughter involves a loss of self-control that can lead to 38 violence. And so in the ideal state described in his Republic and Laws, Plato puts 39 tight restrictions on the performance of comedy. 40 This negative assessment of laughter, humor, and comedy influenced early 41 Christian thinkers, who derived from the Bible a similar understanding of laughter 42 as hostile. The classic statement of the Superiority Theory is that of Thomas 394 Abstracts 1 Hobbes, who describes laughter as an expression of »sudden glory«. Henri Bergson’s 2 account of laughter in Le Rire incorporates a version of the Superiority Theory. 3 For any version of the Superiority Theory to be correct, two things must be true 4 when we laugh: we must compare ourselves with someone else or with our former 5 selves, and in that comparison we must judge our current selves superior.