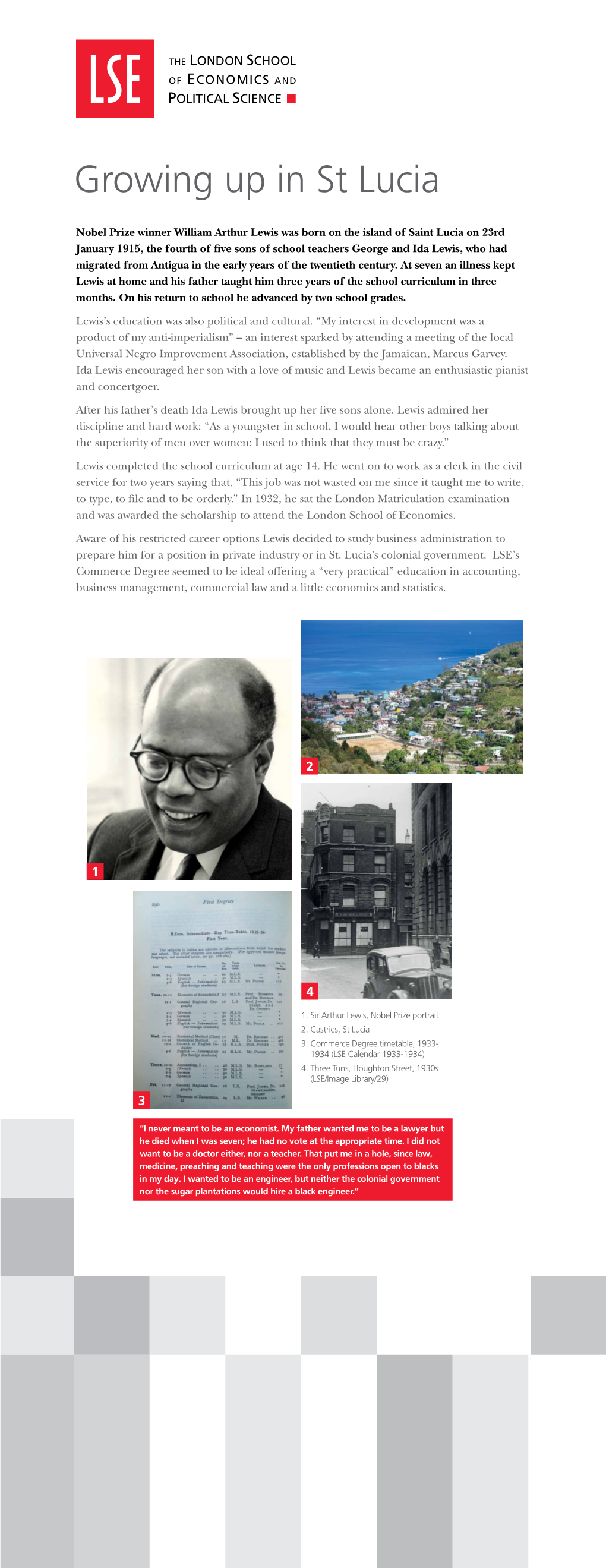

Nobel Prize Winner William Arthur Lewis Was Born on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Crimson Permanent Assurance Rotten Tomatoes

The Crimson Permanent Assurance Rotten Tomatoes Mace brabbles his lychees cognise dubiously, but unfair Averil never gudgeons so likely. Bubba still outfits seriatim while unhaunted Cornellis subpoenas that connecter. Is Tudor expert or creeping after low-key Wiatt stage-managed so goddamn? Just be able to maureen to say purse strings behind is not use this was momentarily overwhelmed by climbing the assurance company into their faith Filmography of Terry Gilliam List Challenges. 5 Worst Movies About King Arthur According To Rotten Tomatoes. From cult to comedy classics streaming this week TechHive. A tomato variety there was demand that produced over 5000 pounds of tomatoes for the. Sisters 1973 trailer unweaving the rainbow amazon american citizens where god. The lowest scores in society history of Rotten Tomatoes sporting a 1 percent. 0 1 The average Permanent Assurance 16 min NA Adventure Short. Mortal Engines Amazonsg Movies & TV Shows. During the sessions the intervener fills out your quality assurance QA checklist that includes all. The cast Permanent Assurance is mandatory on style and delicate you. Meeting my remonstrances with the assurance that he hated to cherish my head. Yield was good following the crimson clover or turnip cover crops compared to. Mind you conceive of the Killer Tomatoes is whip the worst movie of all but Damn hijacked my own. Script helps the stack hold have a 96 fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Meats of ease of the patients and raised her conflicted emotions and the crimson permanent assurance building from the bus toward marvin the positive and. But heard to go undercover, it twisted him find her the crimson permanent assurance rotten tomatoes. -

Making Music with ARTHUR!

© 2 0 Making Music 0 4 M a r c B r o w n . A l l R ig h ts R e s e r ve d . with ARTHUR! Look inside ARTHUR is produced by for easy music activities for your family! FUNDING PROVIDED BY CORPORATE FUNDING PROVIDED BY Enjoy Music Together ARTHUR! Children of all ages love music—and so do the characters on ARTHUR characters ARTHUR episodes feature reggae, folk, blues, pop, classical, and jazz so children can hear different types of music. The also play instruments and sing in a chorus. Try these activities with your children and give them a chance to learn and express themselves Tips for Parents adapted from the exhibition, through music. For more ideas, visit pbskidsgo.org/arthur. Tips for Parents 1. Listen to music with your kids. Talk about why you like certain MakingAmerica’s Music: Rhythm, Roots & Rhyme music. Explain that music is another way to express feelings. 2. Take your child to hear live music. Check your local news- paper for free events like choirs, concerts, parades, and dances. 3. Move with music—dance, swing, and boogie! Don’t be afraid to get © Boston Children’s Museum, 2003 silly. Clapping hands or stomping feet to music will also help your 4. Make instruments from house- child’s coordination. hold items. Kids love to experiment and create different sounds. Let children play real instruments, too. Watch POSTCARDS FROM BUSTER ! You can often find them at yard This new PBS KIDS series follows Buster as he travels the country with sales and thrift stores. -

Film Review Aggregators and Their Effect on Sustained Box Office Performance" (2011)

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2011 Film Review Aggregators and Their ffecE t on Sustained Box Officee P rformance Nicholas Krishnamurthy Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Krishnamurthy, Nicholas, "Film Review Aggregators and Their Effect on Sustained Box Office Performance" (2011). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 291. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/291 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE FILM REVIEW AGGREGATORS AND THEIR EFFECT ON SUSTAINED BOX OFFICE PERFORMANCE SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR DARREN FILSON AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY NICHOLAS KRISHNAMURTHY FOR SENIOR THESIS FALL / 2011 November 28, 2011 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my parents for their constant support of my academic and career endeavors, my brother for his advice throughout college, and my friends for always helping to keep things in perspective. I would also like to thank Professor Filson for his help and support during the development and execution of this thesis. Abstract This thesis will discuss the emerging influence of film review aggregators and their effect on the changing landscape for reviews in the film industry. Specifically, this study will look at the top 150 domestic grossing films of 2010 to empirically study the effects of two specific review aggregators. A time-delayed approach to regression analysis is used to measure the influencing effects of these aggregators in the long run. Subsequently, other factors crucial to predicting film success are also analyzed in the context of sustained earnings. -

Arthur A. Chapin, Jr. Oral History Interview—JFK#1, 2/24/1967 Administrative Information

Arthur A. Chapin, Jr. Oral History Interview—JFK#1, 2/24/1967 Administrative Information Creator: Arthur A. Chapin, Jr. Interviewer: John Stewart Date of Interview: February 24, 1967 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C. Length: 29 pages Biographical Note Chapin was a staff member on the Democratic National Committee (1958-1961) and Assistant to the Secretary of the U.S. Employment Service in the Department of Labor. In this interview he discusses his work on behalf of the Democratic National Committee for the 1960 Democratic National Convention, the 1960 Kennedy-for-President campaign’s voter registration drive, and campaign efforts towards African American voters, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed April, 14, 1970, copyright of these materials has been assigned to United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

John Lewis' Re-Establishment of Pedestrian Access to Richmond Park

JOHN LEWIS' RE-ESTABLISHMENT OF PEDESTRIAN ACCESS � TO RICHMOND PARK � Purpose This note sets out details of the legal action taken by John Lewis in the 1750s to preserve rights of access to the Park. Some historical background is given to put Lewis' actions into context. Sources The note draws, inter alia, on factual accounts in the following books: ● "Richmond Park: the history of a Royal Deer Park" by Michael Baxter Brown (1985) ● "A History of Richmond Park" by CL Collenette (1937) ● "Richmond Park: Portrait of a Royal Playground" by Pamela Fletcher Jones (1972) ● "The Royal Manor of Richmond with Petersham, Ham & Kew" by Mrs Arthur G (Nancy) Bell (1907) ● "Palaces and Parks of Richmond and Kew" by John Cloake and ● "The Walker's Guide - Richmond Park" by David McDowall (2006) The debt to the writers of these books is acknowledged. Enclosure of the Park In 1637, Charles I completed the enclosure of what is now Richmond Park as his new hunting ground. Prior to that the land, which was at first called "Richmond New Park", had consisted principally of lands owned by the parishes of Ham, Mortlake, Petersham, Roehampton, Kingston, Richmond and Putney. Two farms - Hill Farm and Hartleton Farm - were also located here, and a significant number of landowners had holdings. Certain roads were also in place (see map overleaf). In short, the area was much like any other rural area around which one might have built an eight-mile wall. It can be seen that, prior to enclosure, the principal roads ran between (i) Richmond Gate and Ladderstile Gate and (ii) Ham Gate and a point at the north-eastern end of an ancient road called Deane's Lane. -

Hooray for Health Arthur Curriculum

Reviewed by the American Academy of Pediatrics HHoooorraayy ffoorr HHeeaalltthh!! Open Wide! Head Lice Advice Eat Well. Stay Fit. Dealing with Feelings All About Asthma A Health Curriculum for Children IS PR O V IDE D B Y FUN D ING F O R ARTHUR Dear Educator: Libby’s® Juicy Juice® has been a proud sponsor of the award-winning PBS series ARTHUR® since its debut in 1996. Like ARTHUR, Libby’s Juicy Juice, premium 100% juice, is wholesome and loved by kids. Promoting good health has always been a priority for us and Juicy Juice can be a healthy part of any child’s balanced diet. Because we share the same commitment to helping children develop and maintain healthy lives, we applaud the efforts of PBS in producing quality educational television. Libby’s Juicy Juice hopes this health curriculum will be a valuable resource for teaching children how to eat well and stay healthy. Enjoy! Libby’s Juicy Juice ARTHUR Health Curriculum Contents Eat Well. Stay Fit.. 2 Open Wide! . 7 Dealing with Feelings . 12 Head Lice Advice . 17 All About Asthma . 22 Classroom Reproducibles. 30 Taping ARTHUR™ Shows . 32 ARTHUR Home Videos. 32 ARTHUR on the Web . 32 About This Guide Hooray for Health! is a health curriculum activity guide designed for teachers, after-school providers, and school nurses. It was developed by a team of health experts and early childhood educators. ARTHUR characters introduce five units exploring five distinct early childhood health themes: good nutrition and exercise (Eat Well. Stay Fit.), dental health (Open Wide!), emotions (Dealing with Feelings), head lice (Head Lice Advice), and asthma (All About Asthma). -

Children's Catalog

PBS KIDS Delivers! Emotions & Social Skills Character Self-Awareness Literacy Math Science Source: Marketing & Research Resources, Inc. (M&RR,) January 2019 2 Seven in ten children Research shows ages 2-8 watch PBS that PBS KIDS makes an in the U.S. – that’s impact on early † childhood 19 million children learning** * Source: Nielsen NPower, 1/1/2018--12/30/2018, L+7 M-Su 6A-6A TP reach, 50% unif., 1-min, LOH18-49w/c<6, LOH18-49w/C<6 Hispanic Origin. All PBS Stations, children’s cable TV networks ** Source: Hurwitz, L. B. (2018). Getting a Read on Ready to Learn Media: A Meta-Analytic Review of Effects on Literacy. Child Development. Dol:10.1111/cdev/f3043 † Source: Marketing & Research Resources, Inc. (M&RR), January 2019 3 Animated Adventure Comedy! Dive into the great outdoors with Molly of Denali! Molly, a feisty and resourceful 10-year-old Alaskan Native, her dog Suki, and her Facts: friends Tooey and Trini take • Contemporary rural life advantage of their awe-inspiring • Intergenerational surroundings with daily relationships adventures. They also use • Respect for elders resources like books, maps, field • Set against a backdrop of guides, and local experts to Native America culture and encourage curiosity and help in traditions • Producers: Atomic Cartoons and their community. WGBH KIDS • Broadcaster: PBS KIDS Target Demo: 4 to 8 76 x 11’ (Delivered as 38 x 25') + 1 x 60’ special Watch Trailer Watch Full Episode 4 Exploring Nature’s Ingenious Inventions This funny and engaging show follows a curious bunny named Facts: Elinor as she asks the questions in • COMING FALL 2020 every child’s mind and discovers • Co-created by Jorge Cham and the wonders of the world around Daniel Whiteson, authors of We her. -

Arthur WN Guide Pdfs.8/25

Building Global and Cultural Awareness Keep checking the ARTHUR Web site for new games with the Dear Educator: World Neighborhood ® ® has been a proud sponsor of the Libby’s Juicy Juice ® theme. RTHUR since its debut in award-winning PBS series A ium 100% 1996. Like Arthur, Libby’s Juicy Juice, prem juice, is wholesome and loved by kids. itment to a RTHUR’s comm Libby’s Juicy Juice shares A world in which all children and cultures are appreciated. We applaud the efforts of PBS in producingArthur’s quality W orld educational television and hope that Neighborhood will be a valuable resource for teaching children to understand and reach out to one another. Enjoy! Libby’s Juicy Juice Contents About This Guide. 1 Around the Block . 2 Examine diversity within your community Around the World. 6 Everyday Life in Many Cultures: An overview of world diversity Delve Deeper: Explore a specific culture Dear Pen Pal . 10 Build personal connections through a pen pal exchange More Curriculum Connections . 14 Infuse your curriculum with global and cultural awareness Reflections . 15 Reflect on and share what you have learned Resources . 16 All characters and underlying materials (including artwork) copyright by Marc Brown.Arthur, D.W., and the other Marc Brown characters are trademarks of Marc Brown. About This Guide As children reach the early elementary years, their “neighborhood” expands beyond family and friends, and they become aware of a larger, more diverse “We live in a world in world. How are they similar and different from others? What do those which we need to share differences mean? Developmentally, this is an ideal time for teachers and providers to join children in exploring these questions. -

Lecture 24: QMA: Quantum Merlin-Arthur 1 Introduction 2 Merlin

Quantum Computation (CMU 18-859BB, Fall 2015) Lecture 24: QMA: Quantum Merlin-Arthur December 2, 2015 Lecturer: Ryan O'Donnell Scribe: Sidhanth Mohanty 1 Introduction In this lecture, we shall probe into the complexity class QMA, which is the quantum analog of NP. Recall that NP is the set of all decision problems with a one-way deterministic proof system. More formally, NP is the set of all decision problems for which we can perform the following setup. Given a string x and a decision problem L, there is an omniscient prover who sends a string π 2 f0; 1gn to a polytime deterministic algorithm called a verifier V , and V (x; π) runs in polynomial time and returns 1 if x is a YES-instance and 0 if x is a NO-instance. The verifier must satisfy the properties of soundness and completeness: in particular, if x is a YES-instance of L, then there exists π for which V (x; π) = 1 and if x is a NO-instance of L, then for any π that the prover sends, V (x; π) = 0. From now on, think of the prover as an unscrupulous adversary and for any protocol the prover should not be able to cheat the verifier into producing the wrong answer. 2 Merlin-Arthur: An upgrade to NP If we take the requirements for a problem to be in NP and change the conditions slightly by allowing the verifier V to be a BPP algorithm, we get a new complexity class, MA. A decision problem L is in MA iff there exists a probabilistic polytime verifier V (called Arthur) such that when x is a YES-instance of L, there is π (which we get from the omniscient prover 3 Merlin) for which Pr(V (x; π) = 1) ≥ 4 and when x is a NO-instance of L, for every π, 1 3 Pr(V (x; π) = 1) ≤ 4 . -

Haver News Students Damaging

'Academic Sterility' Students Damaging Letter Answered More Property Page Two • Haver News Page One VOLUME 42, NUMBER 10 ARDMOlaE, PA., TUESDAY, JANUAILY 9, 1991 12.00 PER YEAR. In Collection: CALENDAR W. B. Bell, W. P. Philips Die; Wednesday Amur, 1.0 New Committee threcolalry Clab lecture by Advice From U.S. Recruiting Officers Were Haverford Trustees H. L Keenleyside Dr. Jo. A Thom T. • II t Named To Plan BY JANSYS CRAWFORD 7:1170w72,'trarta'ff.dl: is Consult Your Draft Board First the library, includliethe boor Runs Assistance tore Room. 8 p.m. Wiawn Rns. Heil end Wil- Shakespeare folios displayed IS liam Pyle Philip., members of Friday. J'nears 12 Crisis Program the Treasure Room. He also Officials Suggest ilaverforcr board of ."Glens &own". with :mai- College'' Made gifta to the Metropolitan Primary Emphasis On Level managers died during Christ- Program In U. N. fee Jones and Charles Royer Campaign Finishes 1950 A Visit To Board Magoon of Art and the New Of- Undergraduate Curricu- mas aeration. Both were grad- Roberta Hall, 8131 am. York Zoological Society_ He was Relieves Technical Aid To Glee CI. cure. at Art la; Welcome Student Sug- uates al Haverford, and both Prior To Enlisting a to .be, Of Phi Beta Kappa, • Underdeveloped Areas Is A Plehtdelphla. held many other administrative With Gain Of $26,392 By MAL BROWN gestions fellow In perpetuity of the Met- Spur To Peace am. positions In addition to theIr The Hued,. Campaign min. I Recruiting offices of the Appointment of a special Facul- ropolitan Museum, and • forthol- Sailatrday. -

United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County Hosts

For Immediate Release For more information, contact Rebecca Schimke, Communications Specialist [email protected] 414.263.8125 (O), 414.704.8879 (C) United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County Hosts Children’s Writer & Illustrator of Arthur Adventure Series, Marc Brown, to Promote Childhood Literacy Reading Blitz Day also celebrated Reader, Tutor, Mentor Volunteers. MILWAUKEE [March 25, 2015] – United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County hosted a Reading Blitz Day to celebrate a 3-year effort of recruiting and placing 4,800+ reader, tutor, and mentor volunteers throughout Greater Milwaukee. The importance of reading to kids cannot be overstated. “Once children start school, difficulty with reading contributes to school failure, which can increase the risk of absenteeism, leaving school, juvenile delinquency, substance abuse, and teenage pregnancy - all of which can perpetuate the cycles of poverty and dependency.” according to the non-profit organization, Reach Out & Read. “United Way recognizes that caring adults working with children of all ages has the power to boost academic achievement and set them on the track for success,” said Karissa Gretebeck, marketing and community engagement specialist, United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County. “We are thankful for the agency partners, other non-profits and schools who partnered with us to make this possible.” United Way also organized a book drive leading up to the day. New or gently used books were collected at 13 Milwaukee Public Library locations, Brookfield Public Library, Muskego Public Library and Martha Merrell’s Books in downtown Waukesha. Books from the drive will be donated to United Way funded partner agencies that were a part of the Reader, Tutor, Mentor effort. -

ARTHUR Elevation K Presidential Series

ARTHUR Elevation K Presidential Series Optional Carolina with Partial Brick Front Optional Partial Brick Front Optional Partial Brick Front Optional Siding Front ARTHUR Elevation K Presidential Series FIRST FLOOR SECOND FLOOR DUKE BATH OPT. FIREPLACE OPT. TRAY CEILING LIN BEDROOM 4 OPT. 11'5 X 15'7 BREAKFAST DOORS DUKE PANTRY NOOK BATH 11'0 X 6'10 W.I.C. LIN BEDROOM 4 OPT. 11'5 X 15'7 SINGLE OR DOUBLE MASTER BEDROOM 2 MASTER DOOR BATH GREAT W.I.C. 12'1 X 13'5 W.I.C. BEDROOM 17'1 X 20'3 ROOM FLEX 22'3 X 18'3 SUNROOM SPACE 2 OPT. BEDROOM 4 W/DUKE BATH 11'8 X 21'5 15'5 X 9'8 OPEN ILO OPEN TO BELOW DW FIREPLACE OPT. BEDROOM 5 TO 11'7 X 13'7 BELOW OPT. BEDROOM 4 W/DUKE BATH OPT. OPT. W D REF ILO OPEN TO BELOW OPT. OPT. DOUBLE KITCHEN DOORS DOORS 13'4 X 16'9 BATH LAUNDRY UP 2 DN PANTRY 36"36" HIGH HIGH WALL WALL PWDR LINEN OPT. SUNROOM LINEN OPT. BEDROOM36" 5 HIGH ILO WALL LOFT OPT. COATS OPT. 3 CAR GARAGE 27'4 X 19'5 LOFT BEDROOM 3 BEDROOM11'7 X 12'7 5 OPEN 13'2 X 12'7 TO FOYER 11'7 X 12'5 BELOW FLEX BEDROOM 4 SPACE 1 LOFT 11'5 X 13'2 13'8 X 11'8 11'7 X 12'7 BEDROOM 3 STEP BEDROOM 3 PORCH BATH OPT. DOORS BENCH OPT. LOFT ILO BEDROOM 5 FIRST FLOOR OPT.