The Intersection of Merits and Judicial Review: Looking Forward1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

$Fu the Federal Redistribution 2008 .*

TheFederal Redistribution 2008 $fu .*,,. s$stqf.<uaf TaSmania \ PublicComment Number 6 HonMichael Hodgman QC MP 3 Page(s) HON MICHAEL HODGMAN QC MP Parliament House Her Maj esty's ShadowAttorney-General HOBART TAS TOOO for the Stateof Tasmania ShadowMinister for Justice Phone: (03)6233 2891 and WorkplaceRelations Fax: (03)6233 2779 Liberal Member for Denison michael.hodgman@ parliament.tas.gov.au The FederalDistribution 2008 RedistributionCommittee for Tasmania 2ndFloor AMP Building 86 CollinsStreet HOBART TAS TOOO Attention: Mr David Molnar Dear Sir, As foreshadowedin my letter to you of 28 April, I now wish to formally obiectto the Submissionscontained in Public SuggestionNo.2 and Public SuggestionNo. 16 that the nameof the Electorateof Denisonshould be changedto Inglis Clark. I havehad the honour to representthe Electorate of Denisonfor over 25 yearsin both the FederalParliament and the State Parliamentand I havenot, in that entire time, had onesingle elector ever suggestto me that the nameof the Electorateshould be changedfrom Denisonto Inglis Clark. The plain fact is that the two southernTasmanian Electoratesof Denisonand Franklin havebeen known as a team,a pair and duo for nearly a century; they havealways been spoken of together; and, the great advantageto the Australian Electoral systemof the two Electoratesbeing recognised as a team,a pair and a duo,would be utterly destroyedif oneof them were to suffer an unwarrantedname change. Whilst I recognisethe legaland constitutionalcontributions of Andrew Inglis Clark the plain fact is that his namewas never put forward by his contemporariesto be honouredby havinga FederalElectorate named after him. Other legal and constitutionalcontributors like Barton, Parkes, Griffith and Deakin were honoured by having Federal Electoratesnamed after them - but Inglis Clark was not. -

Ceremonial Sitting of the Tribunal for the Swearing in and Welcome of the Honourable Justice Kerr As President

AUSCRIPT AUSTRALASIA PTY LIMITED ABN 72 110 028 825 Level 22, 179 Turbot Street, Brisbane QLD 4000 PO Box 13038 George St Post Shop, Brisbane QLD 4003 T: 1800 AUSCRIPT (1800 287 274) F: 1300 739 037 E: [email protected] W: www.auscript.com.au TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS O/N H-59979 ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL CEREMONIAL SITTING OF THE TRIBUNAL FOR THE SWEARING IN AND WELCOME OF THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR AS PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR, President THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KEANE, Chief Justice of the Federal Court of Australia THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE BUCHANAN, Presidential Member DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.D. HOTOP DEPUTY PRESIDENT R.P. HANDLEY DEPUTY PRESIDENT D.G. JARVIS THE HONOURABLE R.J. GROOM, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT P.E. HACK SC DEPUTY PRESIDENT J.W. CONSTANCE THE HONOURABLE B.J.M. TAMBERLIN QC, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.E. FROST DEPUTY PRESIDENT R. DEUTSCH PROF R.M. CREYKE, Senior Member MS G. ETTINGER, Senior Member MR P.W. TAYLOR SC, Senior Member MS J.F. TOOHEY, Senior Member MS A.K. BRITTON, Senior Member MR D. LETCHER SC, Senior Member MS J.L REDFERN PSM, Senior Member MS G. LAZANAS, Senior Member DR I.S. ALEXANDER, Member DR T.M. NICOLETTI, Member DR H. HAIKAL-MUKHTAR, Member DR M. COUCH, Member SYDNEY 9.32 AM, WEDNESDAY, 16 MAY 2012 .KERR 16.5.12 P-1 ©Commonwealth of Australia KERR J: Chief Justice, I have the honour to announce that I have received a commission from her Excellency, the Governor General, appointing me as President of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. -

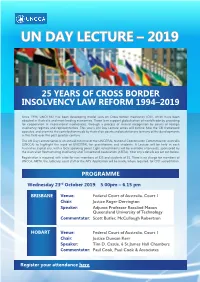

Un Day Lecture – 2019

UN DAY LECTURE – 2019 25 YEARS OF CROSS BORDER INSOLVENCY LAW REFORM 1994–2019 Since 1994, UNCITRAL has been developing model laws on Cross Border Insolvency (CBI), which have been adopted in Australia and most leading economies. These laws support globalisation of world trade by providing for cooperation in international insolvencies, through a process of mutual recognition by courts of foreign insolvency regimes and representatives. This year’s UN Day Lecture series will outline how the CBI framework operates, and examine the contribution made by Australian courts and practitioners to many of the developments in this field over the past quarter-century. The UN Day Lecture series is an annual initiative of the UNCITRAL National Coordination Committee for Australia (UNCCA) to highlight the work of UNCITRAL for practitioners and students. A Lecture will be held in each Australian capital city, with a local speaking panel. Light refreshments will be available afterwards, sponsored by the Australian Restructuring Insolvency and Turnaround Association (ARITA). Your city’s details are set out below. Registration is required, with a fee for non-members of $25 and students of $5. There is no charge for members of UNCCA, ARITA, the Judiciary, court staff or the APS. Application will be made, where required, for CPD accreditation. PROGRAMME Wednesday 23rd October 2019: 5.00pm – 6.15 pm BRISBANE Venue: Federal Court of Australia, Court 1 Chair: Justice Roger Derrington Speaker: Adjunct Professor Rosalind Mason Queensland University of Technology Commentator: Scott Butler, McCullough Robertson HOBART Venue: Federal Court of Australia, Court 1 Chair: Justice Duncan Kerr Speaker: Tim D. -

Inaugural Speech – Felix Ashton Ellis MP

Ella Hadded MP House of Assembly Date: 2 May 2018 Electorate: Denison Ms HADDAD (Denison - Inaugural) - Madam Speaker, what an honour to be standing in this place with the opportunity to give my first speech. It might be an honour that I have long imagined, but not one I necessarily thought I would have the chance to fulfil. I start by congratulating all members on their re-election and recognising my fellow incoming members - yourself, Madam Speaker, together with Anita, Alison, Jenna, and Jennifer, and David returning in his role as member for Franklin. To my fellow Labor member for Denison, Scott Bacon, I very much look forward to serving the electorate with you. I also pay tribute and acknowledge Madeleine Ogilvie, who served Denison in the last four years with distinction. I wish her all the very best in her continuing legal career. Madam Speaker, I believe our parliament should reflect our peers. It should be made up of people from across our communities who have a range of experiences in work and life and who will bring those experiences to their work here. I started working when I was 14 in restaurants and hospitality. Coming from a family in small business, I learned the value of hard work early. I learned the value of always looking for more to do, working hard at every task you have and doing the very best you can. My parents taught me to always have a healthy questioning of authority, not a disrespect, but simply to ask myself what is fair and right and what I could do to make a difference when I saw injustice. -

House of Assembly Wednesday 2 May 2018

Wednesday 2 May 2018 The Speaker, Ms Hickey, took the Chair at 10 a.m., acknowledged the Traditional People, and read Prayers. QUESTIONS Royal Hobart Hospital - Emergency Department Issues Ms WHITE question to PREMIER, Mr HODGMAN [10.02 a.m.] Did you know that yesterday there were 63 patients stuck in the emergency department at the Royal Hobart Hospital, patients were being treated in three corridors, and there were 10 ambulances ramped? This is bad for patients and bad for stressed staff. If anything, it looks like this winter will be worse than last winter. Why was the hospital not escalated to level 4, as staff were asking for? Was there political pressure not to escalate due to the parliament resuming? ANSWER Madam Speaker, I thank the Leader of the Opposition for the question but would cast a very healthy level of scepticism over any suggestions from her as to what this Government might do other than ensure we get on with the job of delivering on our record level of investment and commitments that will go to delivering the health service, which is improving under our Government and that we promised in the election. That is what we are focusing on. We recognise that there are pressures on the health system. That is why, with our budget back in balance, we have been able to commit a record amount over the last four years, $7 billion in the last budget and $750 million, to boost our efforts to improve the health system Tasmanians need. We will need to not only build the health system and the infrastructure to support it - Members interjecting. -

2845 Australian National University

2845 AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY NATIONAL LAW REFORM CONFERENCE CANBERRA, 15 APRIL 2016 ACADEMIC AND INSTITUTIONAL LAW REFORM IN AUSTRALIA: PAST, PASSING AND TO COME The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY NATIONAL LAW REFORM CONFERENCE CANBERRA, 15 APRIL 2016 ACADEMIC AND INSTITUTIONAL LAW REFORM IN AUSTRALIA: PAST, PASSING AND TO COME The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG* Once out of nature I shall never take My bodily form from any natural thing, But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make Of hammered gold and gold enamelling To keep a drowsy emperor awake; Or set upon a golden bow to sing To lords and ladies of Byzantium Of what is past, or passing, or to come W.B. Yeats1 I. ACADEMIC What is Past It is surprising that it has taken until 2016 to summon together Australia’s academic talent to describe the wealth of scholarly projects addressed to law reform. Systematic law reform, of course, has been on the academic and professional agenda for decades. Long before institutional responses to the needs for law reform were created, judges, * Justice of the High Court of Australia (1996-2009); President of the New South Wales Court of Appeal (1984- 96); Judge of the Federal Court of Australia (1983-4); Chairman of the Australian Law Reform Commission (1975-84). 1 W.B. Yeats, “Sailing to Byzantium” (1927) in W.B. Yeats, Collected Poems (Macmillan, London, 1933), 218. 1 practitioners and scholars would frequently come together, or separately, to propose aspects of the law that needed change. In the manner of those times, specific law reform statutes were copied from England, as in the Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1946 (NSW)2 and the Law Reform (Tortfeasors’ Contribution) Act 1952 (Qld).3 Pleas were made for the better reform of the law.4 Conferences addressed particular aspects of reform. -

Judicial Impartiality Consultations February –April 2021

JUDICIAL IMPARTIALITY CONSULTATIONS FEBRUARY –APRIL 2021 Name Location Professor Rachel Field, Bond University Brisbane Professor Blake McKimmie, University of Queensland Professor Simon Young, University of Southern Queensland Associate Professor Francesca Bartlett, University of Queensland Associate Professor Narelle Bedford, Bond University Dr Rebecca Ananian-Welsh, University of Queensland The Hon Justice Glenn Martin AM, Supreme Court of Queensland and Brisbane President, Australian Judicial Officers’ Association The Hon Chief Justice William Alstergren, Family Court of Australia and Chief Melbourne* Judge, Federal Circuit Court of Australia The Hon Deputy Chief Justice McClelland, Family Court of Australia David Pringle, Chief Executive Officer and Principal Registrar, Family Court of Australia and Federal Circuit Court of Australia Tim Goodwin, Barrister Melbourne* The Hon Peter Heerey AM QC Melbourne* Helen Rofe QC, Barrister Melbourne* Michael Pearce SC, Barrister Georgina Costello QC, Barrister Bronwyn Lincoln, Corrs Chambers Westgarth Rowena Orr QC, Barrister Paul Willee RFD QC, Barrister Minal Vohra SC, Barrister Geoffrey Dickson QC, Barrister Caroline Counsel, CC Family Lawyers John Farrell, Law Council of Australia Nazim El-Bardouh, Muslim Legal Network Melbourne* Tanja Golding, LQBTQI Legal Service David Manne, Refugee Legal Adrian Snodgrass, Fitzroy Legal Service Name Location Ella Crotty, Fitzroy Legal Service Melbourne* Alison Birchall, Domestic Violence Victoria Jennie Child, Domestic Violence Victoria Sulaika Dhanapala, -

Appendix 8: Speeches, Publications and Other Activities

APPENDIX 8: SPEECHES, PUBLICATIONS AND OTHER ACTIVITIES Tribunal members and staff undertake a wide range of activities that assist to raise awareness of the Tribunal’s role, procedures and activities. Members and staff give speeches at conferences and seminars, participate in training and education activities, publish articles and undertake other engagement activities. The record of activities for 2013–14 is in four lists: speeches and presentations; competition adjudication and training; publications; and other engagement activities. The lists in Tables A8.1, A8.2 and A8.4 are arranged by date and the list in Table A8.3 is in alphabetical order. Table A8.1 Speeches and presentations Participant/ Title/role Event/organisation speaker(s) Date The Role of the AAT Tribunal Advocacy Course, Conference 1 July 2013 Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Registrar Siobhan Ni Canberra Fhaolain Administrative Law 2013 National Administrative Law Justice Duncan Kerr, 19 July 2013 in an Interconnected Conference, Australian Institute President World: Where to from of Administrative Law, Canberra here? After the Shooting Biennial Member and Staff Justice Duncan Kerr, 7 August 2013 Stops Conference, Veterans’ Review President Board, Brisbane Diagnosing Psychiatric Biennial Member and Staff Member Dr Marian 7 August 2013 Disorders Conference, Veterans’ Review Sullivan Board, Brisbane Appraisal including Claims Assessment and Senior Member 14 August 2013 Peer Review Resolution Service, NSW Motor Bernard McCabe Accidents Authority, Sydney Keeping the AAT from -

Chapter Four: a Virtuous Circle? the 41St Parliament of Australia and the People’S Republic of China

Chapter Four: A Virtuous Circle? The 41st Parliament of Australia and the People’s Republic of China The Governments in both countries are closely working together to achieve a virtuous circle in the Sino–Australia relationship.1 During the period of the 41st Parliament, November 2004–October 2007, there was considerable growth and diversification in the Australia–China relationship. The economic complementarities which became a hallmark of the relationship during the previous Parliament provided an impetus for the signing of a number of agreements in areas such as the transfer of nuclear materials, mutual legal assistance, extradition and prisoner exchange and cooperative research on bio-security. Such agreements were accompanied by new capacity building projects focusing on water resource management, legal governance and reversing the spread of HIV/AIDS in China. High- level bilateral visits were utilised to mark a number of significant landmarks in relations. During a visit to Beijing in April 2005, Prime Minister Howard announced that Australia and China would commence talks with China on a Free Trade Agreement (FTA), while in April 2006, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao visited Australia and signed a bilateral safeguards agreement on the transfer of nuclear material between Australia and China.2 The Chinese Premier‘s visit was followed by John Howard‘s ‗important, symbolic visit‘ to southern China in June 2006, to witness the first delivery of Australian liquefied natural gas. The Chairman of the National People‘s Congress, Wu Bangguo, also visited Australia during the period to claim, in a speech in the Great Hall at Parliament House, that ‗China–Australia relations are in their best shape in their history‘.3 The developing multilayered character of the bilateralism was underscored by the agreement signed by President Hu Jintao and Prime Minister John Howard during the 1. -

The Hon Nicola Roxon Mp Media Release

THE HON NICOLA ROXON MP Attorney-General Minister for Emergency Management MEDIA RELEASE 12 April 2012 APPOINTMENT OF PRESIDENT OF THE ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL AND FEDERAL COURT JUDGE Attorney-General Nicola Roxon today announced the Government’s intention to recommend to Her Excellency the Governor-General the appointment of two Federal Court of Australia judges, one of whom will serve as the President of the Administrative Appeal Tribunal. Dr Griffiths is a barrister from New South Wales, who was appointed Senior Counsel in 2001; his areas of speciality include administrative law, competition law, environmental and planning law, Aboriginal land rights, commercial law, appellate practice, revenue law, broadcasting and telecommunications law. Dr Griffiths will be assigned to the Sydney Registry. Mr Kerr is a barrister from Tasmania, who was appointed Senior Counsel in 2004; his work focuses on constitutional law, administrative law and appellate work. As well as appearing as counsel before the High Court, Mr Kerr has previously served as a Minister of the Crown. Mr Kerr will be only the second Tasmanian appointed to the Federal Court, and the first in over 25 years. He is also the first President of the AAT appointed from a state other than NSW, Victoria or Queensland, which reflects this Government’s commitment to a greater diversity of appointees to judicial positions. Mr Kerr will take up his appointment as judge and President of the Tribunal following the retirement of the Hon Justice Garry Downes. An advisory panel comprising Chief Justice Patrick Keane, Sir Gerard Brennan AC KBE, the Hon Acting Justice Jane Mathews AO and a senior representative of the Attorney-General’s Department considered candidates for both appointments. -

Pacific Parliamentary Leadership Dialogue 8 – 13 February 2012 Canberra

centre for democratic institutions Pacific Parliamentary Leadership Dialogue 8 – 13 February 2012 Canberra Introduction The Pacific Parliamentary Leadership Dialogue (the Dialogue) was held in Canberra from Wednesday, 8 February to Monday, 13 February 2012. The intensive 4-day Dialogue was structured around a weekend to ensure participants had free time. The Dialogue was designed for a select group of influential and emerging parliamentarians from across the Pacific to reflect on what it means to be a parliamentarian today and to consider what they as individuals can do to re-vitalize the performance of their parliaments and for their respective parliaments to achieve their full potential. The Dialogue comprised discussions and briefings designed to challenge participants to distinguish between their roles as politician and as parliamentarian; to reflect on the tensions that exist between being a community advocate, member of a governing party or an opposition party, policy maker, legislator and accountability agent; and to consider the critically important contribution that parliament can make to good governance. During the Dialogue participants discussed: . balancing relationships between the parliamentary, executive and judicial branches of government; . exercising parliamentary power, especially law making, policy review and administrative accountability and financial scrutiny powers; and . ethics and integrity in parliamentary leadership. These discussions were informed by meetings with Australian parliamentarians and parliamentary officials and by observing proceedings of the Australian Parliament and its committees. The program will also involve meetings with members and staff from the Australian Capital Territory Legislative Assembly. The Dialogue provided an opportunity for parliamentarians from across the Pacific to consider what they can do to foster new ways of thinking about parliamentary leadership, so that Pacific parliaments can assume their place as effective institutions of government. -

TLP 2016 Year Book

TASMANIAN LEADERS YEARBOOK 2016 LEADERS TASMANIAN YEARBOOK 2016 TASMANIAN LEADERS YEARBOOK 2016 CONTENTS ABOUT TASMANIAN LEADERS..............................................................4 OUR MISSION .....................................................................................................4 OUR VALUES ........................................................................................................5 TASMANIAN LEADERS PROGRAM OUTCOMES .....................5 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR ....................................................................6 MESSAGE FROM THE GENERAL MANAGER .................................8 TLP10 2016 VALEDICTORY SPEECH .................................................10 TLP9 2015 GRADUATION DINNER FEB 2016 ..........................11 TLP10 2016 PROGRAM SUMMARY ..................................................12 TLP10 2016 GRADUATE PROFILES ...................................................20 TLP10 2016 LEARNING SET PROJECTS .........................................44 EMPLOYER TESTIMONIALS .....................................................................46 LEADERSHIP CHAMPIONS .....................................................................48 THANK YOU ......................................................................................................49 TASMANIAN LEADERS BOARD MEMBERS .................................50 ALUMNI SUB-COMMITTEE UPDATE ...............................................52 THINKBANK ......................................................................................................54