Kerr J Opening Address

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

$Fu the Federal Redistribution 2008 .*

TheFederal Redistribution 2008 $fu .*,,. s$stqf.<uaf TaSmania \ PublicComment Number 6 HonMichael Hodgman QC MP 3 Page(s) HON MICHAEL HODGMAN QC MP Parliament House Her Maj esty's ShadowAttorney-General HOBART TAS TOOO for the Stateof Tasmania ShadowMinister for Justice Phone: (03)6233 2891 and WorkplaceRelations Fax: (03)6233 2779 Liberal Member for Denison michael.hodgman@ parliament.tas.gov.au The FederalDistribution 2008 RedistributionCommittee for Tasmania 2ndFloor AMP Building 86 CollinsStreet HOBART TAS TOOO Attention: Mr David Molnar Dear Sir, As foreshadowedin my letter to you of 28 April, I now wish to formally obiectto the Submissionscontained in Public SuggestionNo.2 and Public SuggestionNo. 16 that the nameof the Electorateof Denisonshould be changedto Inglis Clark. I havehad the honour to representthe Electorate of Denisonfor over 25 yearsin both the FederalParliament and the State Parliamentand I havenot, in that entire time, had onesingle elector ever suggestto me that the nameof the Electorateshould be changedfrom Denisonto Inglis Clark. The plain fact is that the two southernTasmanian Electoratesof Denisonand Franklin havebeen known as a team,a pair and duo for nearly a century; they havealways been spoken of together; and, the great advantageto the Australian Electoral systemof the two Electoratesbeing recognised as a team,a pair and a duo,would be utterly destroyedif oneof them were to suffer an unwarrantedname change. Whilst I recognisethe legaland constitutionalcontributions of Andrew Inglis Clark the plain fact is that his namewas never put forward by his contemporariesto be honouredby havinga FederalElectorate named after him. Other legal and constitutionalcontributors like Barton, Parkes, Griffith and Deakin were honoured by having Federal Electoratesnamed after them - but Inglis Clark was not. -

Ceremonial Sitting of the Tribunal for the Swearing in and Welcome of the Honourable Justice Kerr As President

AUSCRIPT AUSTRALASIA PTY LIMITED ABN 72 110 028 825 Level 22, 179 Turbot Street, Brisbane QLD 4000 PO Box 13038 George St Post Shop, Brisbane QLD 4003 T: 1800 AUSCRIPT (1800 287 274) F: 1300 739 037 E: [email protected] W: www.auscript.com.au TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS O/N H-59979 ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL CEREMONIAL SITTING OF THE TRIBUNAL FOR THE SWEARING IN AND WELCOME OF THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR AS PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR, President THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KEANE, Chief Justice of the Federal Court of Australia THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE BUCHANAN, Presidential Member DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.D. HOTOP DEPUTY PRESIDENT R.P. HANDLEY DEPUTY PRESIDENT D.G. JARVIS THE HONOURABLE R.J. GROOM, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT P.E. HACK SC DEPUTY PRESIDENT J.W. CONSTANCE THE HONOURABLE B.J.M. TAMBERLIN QC, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.E. FROST DEPUTY PRESIDENT R. DEUTSCH PROF R.M. CREYKE, Senior Member MS G. ETTINGER, Senior Member MR P.W. TAYLOR SC, Senior Member MS J.F. TOOHEY, Senior Member MS A.K. BRITTON, Senior Member MR D. LETCHER SC, Senior Member MS J.L REDFERN PSM, Senior Member MS G. LAZANAS, Senior Member DR I.S. ALEXANDER, Member DR T.M. NICOLETTI, Member DR H. HAIKAL-MUKHTAR, Member DR M. COUCH, Member SYDNEY 9.32 AM, WEDNESDAY, 16 MAY 2012 .KERR 16.5.12 P-1 ©Commonwealth of Australia KERR J: Chief Justice, I have the honour to announce that I have received a commission from her Excellency, the Governor General, appointing me as President of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. -

The Hon. RJ Ellicott QC Way He Did Not Think Pro P E R Entering Into Partnership

A D D R E S S E S The Hon. R J Ellicott QC: 50 years at the Bar A speech delivered when he moved to Elizabeth by The Hon. Justice R V Gyles B a y. He is pre s e n t l y AO at a dinner to celebrate C h a i rman of Life Education Ellicott QC’s 50 years at the Australia, which does much Ba r , Westin Sydney, 17 good work with dru g November 2000 education programmes for Australian school students. ou can take the boy out He spent 14 years in of the bush, but not the public life as solicitor- Ybush out of the boy. general, a Member of the Bob Ellicott was born House of Representatives, in and raised in Moree, the various ministerial son of a shearer turn e d p o rtfolios, and as a Federal wool classer. Rural intere s t s C o u rt judge. have been one abiding He had, and has, a theme of his life. Since his genuine fascination for days as a junior barr i s t e r, he public affairs. He re s i g n e d has owned rural pro p e rt i e s f rom the Bench in part (not always with Colleen’s because he retained this full approval). When in i n t e rest and did not wish to comparative penury whilst shut himself out of in public service, he p a rticipation in public issues persuaded Trevor Morling and public debate in the to subsidise his interest by The Hon. -

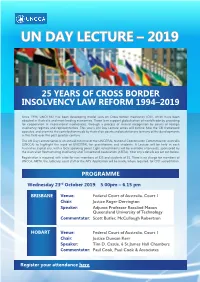

Un Day Lecture – 2019

UN DAY LECTURE – 2019 25 YEARS OF CROSS BORDER INSOLVENCY LAW REFORM 1994–2019 Since 1994, UNCITRAL has been developing model laws on Cross Border Insolvency (CBI), which have been adopted in Australia and most leading economies. These laws support globalisation of world trade by providing for cooperation in international insolvencies, through a process of mutual recognition by courts of foreign insolvency regimes and representatives. This year’s UN Day Lecture series will outline how the CBI framework operates, and examine the contribution made by Australian courts and practitioners to many of the developments in this field over the past quarter-century. The UN Day Lecture series is an annual initiative of the UNCITRAL National Coordination Committee for Australia (UNCCA) to highlight the work of UNCITRAL for practitioners and students. A Lecture will be held in each Australian capital city, with a local speaking panel. Light refreshments will be available afterwards, sponsored by the Australian Restructuring Insolvency and Turnaround Association (ARITA). Your city’s details are set out below. Registration is required, with a fee for non-members of $25 and students of $5. There is no charge for members of UNCCA, ARITA, the Judiciary, court staff or the APS. Application will be made, where required, for CPD accreditation. PROGRAMME Wednesday 23rd October 2019: 5.00pm – 6.15 pm BRISBANE Venue: Federal Court of Australia, Court 1 Chair: Justice Roger Derrington Speaker: Adjunct Professor Rosalind Mason Queensland University of Technology Commentator: Scott Butler, McCullough Robertson HOBART Venue: Federal Court of Australia, Court 1 Chair: Justice Duncan Kerr Speaker: Tim D. -

House of Representatives By-Elections 1902-2002

INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND ADVICE FOR THE PARLIAMENT INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Current Issues Brief No. 15 2002–03 House of Representatives By-elections 1901–2002 DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY ISSN 1440-2009 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2003 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Current Issues Brief No. 15 2002–03 House of Representatives By-elections 1901–2002 Gerard Newman, Statistics Group Scott Bennett, Politics and Public Administration Group 3 March 2003 Acknowledgments The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Murray Goot, Martin Lumb, Geoff Winter, Jan Pearson, Janet Wilson and Diane Hynes in producing this paper. -

Inaugural Speech – Felix Ashton Ellis MP

Ella Hadded MP House of Assembly Date: 2 May 2018 Electorate: Denison Ms HADDAD (Denison - Inaugural) - Madam Speaker, what an honour to be standing in this place with the opportunity to give my first speech. It might be an honour that I have long imagined, but not one I necessarily thought I would have the chance to fulfil. I start by congratulating all members on their re-election and recognising my fellow incoming members - yourself, Madam Speaker, together with Anita, Alison, Jenna, and Jennifer, and David returning in his role as member for Franklin. To my fellow Labor member for Denison, Scott Bacon, I very much look forward to serving the electorate with you. I also pay tribute and acknowledge Madeleine Ogilvie, who served Denison in the last four years with distinction. I wish her all the very best in her continuing legal career. Madam Speaker, I believe our parliament should reflect our peers. It should be made up of people from across our communities who have a range of experiences in work and life and who will bring those experiences to their work here. I started working when I was 14 in restaurants and hospitality. Coming from a family in small business, I learned the value of hard work early. I learned the value of always looking for more to do, working hard at every task you have and doing the very best you can. My parents taught me to always have a healthy questioning of authority, not a disrespect, but simply to ask myself what is fair and right and what I could do to make a difference when I saw injustice. -

House of Assembly Wednesday 2 May 2018

Wednesday 2 May 2018 The Speaker, Ms Hickey, took the Chair at 10 a.m., acknowledged the Traditional People, and read Prayers. QUESTIONS Royal Hobart Hospital - Emergency Department Issues Ms WHITE question to PREMIER, Mr HODGMAN [10.02 a.m.] Did you know that yesterday there were 63 patients stuck in the emergency department at the Royal Hobart Hospital, patients were being treated in three corridors, and there were 10 ambulances ramped? This is bad for patients and bad for stressed staff. If anything, it looks like this winter will be worse than last winter. Why was the hospital not escalated to level 4, as staff were asking for? Was there political pressure not to escalate due to the parliament resuming? ANSWER Madam Speaker, I thank the Leader of the Opposition for the question but would cast a very healthy level of scepticism over any suggestions from her as to what this Government might do other than ensure we get on with the job of delivering on our record level of investment and commitments that will go to delivering the health service, which is improving under our Government and that we promised in the election. That is what we are focusing on. We recognise that there are pressures on the health system. That is why, with our budget back in balance, we have been able to commit a record amount over the last four years, $7 billion in the last budget and $750 million, to boost our efforts to improve the health system Tasmanians need. We will need to not only build the health system and the infrastructure to support it - Members interjecting. -

2845 Australian National University

2845 AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY NATIONAL LAW REFORM CONFERENCE CANBERRA, 15 APRIL 2016 ACADEMIC AND INSTITUTIONAL LAW REFORM IN AUSTRALIA: PAST, PASSING AND TO COME The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY NATIONAL LAW REFORM CONFERENCE CANBERRA, 15 APRIL 2016 ACADEMIC AND INSTITUTIONAL LAW REFORM IN AUSTRALIA: PAST, PASSING AND TO COME The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG* Once out of nature I shall never take My bodily form from any natural thing, But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make Of hammered gold and gold enamelling To keep a drowsy emperor awake; Or set upon a golden bow to sing To lords and ladies of Byzantium Of what is past, or passing, or to come W.B. Yeats1 I. ACADEMIC What is Past It is surprising that it has taken until 2016 to summon together Australia’s academic talent to describe the wealth of scholarly projects addressed to law reform. Systematic law reform, of course, has been on the academic and professional agenda for decades. Long before institutional responses to the needs for law reform were created, judges, * Justice of the High Court of Australia (1996-2009); President of the New South Wales Court of Appeal (1984- 96); Judge of the Federal Court of Australia (1983-4); Chairman of the Australian Law Reform Commission (1975-84). 1 W.B. Yeats, “Sailing to Byzantium” (1927) in W.B. Yeats, Collected Poems (Macmillan, London, 1933), 218. 1 practitioners and scholars would frequently come together, or separately, to propose aspects of the law that needed change. In the manner of those times, specific law reform statutes were copied from England, as in the Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1946 (NSW)2 and the Law Reform (Tortfeasors’ Contribution) Act 1952 (Qld).3 Pleas were made for the better reform of the law.4 Conferences addressed particular aspects of reform. -

Neville Wran – a Lawyer Politician – Reflections on Law Reform and the High Court of Australia

THE PARLIAMENT OF NEW SOUTH WALES THURSDAY, 13 NOVEMBER 2008 INAUGURAL NEVILLE WRAN LECTURE NEVILLE WRAN – A LAWYER POLITICIAN – REFLECTIONS ON LAW REFORM AND THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA The Hon Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG* NEVILLE WRAN’S LIFE & TIMES PARALLEL LIVES This is the inaugural lecture to honour Neville Wran, one of the most successful Australian politicians and lawyers of my lifetime. Over the years I have honoured parliamentarians on all sides of politics. In Melbourne, I gave the Alfred Deakin Lecture, established by those associated with the Liberal Party of Australia. In this Parliament I gave the Earle Page Lecture established to celebrate the life of a leader of the Australian Country Party. Now, the Neville Wran Lecture established by the Australian Labor Party. Yet unlike the British, from whom we otherwise derived so many conventions of political and civic life, Australians tend to observe a highly partisan view of their politicians, * Justice of the High Court of Australia. Personal views and opinions. The writer acknowledges the assistance of his associate, Leonie Young, in respect of some of the biographical materials. 2. even after they have left politics. This is an infantile disorder. We need to grow out of it and acknowledge warmly those who have contributed to our public life. In some respects, my life has run on a parallel course with Neville Wran's. We were both children of families, intelligent but not well off. We both grew up in the western suburbs of Sydney. We both attended selective public schools. We enjoyed the extra-curricula activities of university life. -

The Intersection of Merits and Judicial Review: Looking Forward1

THE INTERSECTION OF MERITS AND JUDICIAL REVIEW: LOOKING FORWARD1 JUSTICE D KERR* Over the past four decades three administrative law revolutions have transformed the legislative and constitutional basis of Australian public law. Judicial review has been constitutionalised and can set aside a decision and compel duties to be performed but it cannot substitute a better decision. Only merits review can substitute a correct or more preferable decision. Merits review is now firmly built into the architecture of the Australian system of government but there is room for further championing of this vital area of administrative law. Critical issues in public law, the requirement of reasons, unreasonableness as a ground of review and the availability of review rights in respect of private bodies exercising public power are explored. I THE FIRST ADMINISTRATIVE LAW REVOLUTION As Dennis Pearce reminds us,2 the establishment of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (‘AAT’) was recommended in the Commonwealth Administrative Review Committee’s (the ‘Kerr Committee’) report of 1971.3 The Committee recognised that the scope and complexity of government intervention in Australian society had grown greatly since federation and was concerned that review of government decisions through Parliament and the courts had provided an inadequate response. The system was flawed both with regard to substance and accessibility. What was needed, it reported, was an accessible, informal and relatively cheap means for obtaining review of the merits of administrative decisions. The AAT was established as a result of the passage of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975 (‘AAT Act’). It was a unique creation of the Australian legal system and, at that time, a world first. -

Judicial Impartiality Consultations February –April 2021

JUDICIAL IMPARTIALITY CONSULTATIONS FEBRUARY –APRIL 2021 Name Location Professor Rachel Field, Bond University Brisbane Professor Blake McKimmie, University of Queensland Professor Simon Young, University of Southern Queensland Associate Professor Francesca Bartlett, University of Queensland Associate Professor Narelle Bedford, Bond University Dr Rebecca Ananian-Welsh, University of Queensland The Hon Justice Glenn Martin AM, Supreme Court of Queensland and Brisbane President, Australian Judicial Officers’ Association The Hon Chief Justice William Alstergren, Family Court of Australia and Chief Melbourne* Judge, Federal Circuit Court of Australia The Hon Deputy Chief Justice McClelland, Family Court of Australia David Pringle, Chief Executive Officer and Principal Registrar, Family Court of Australia and Federal Circuit Court of Australia Tim Goodwin, Barrister Melbourne* The Hon Peter Heerey AM QC Melbourne* Helen Rofe QC, Barrister Melbourne* Michael Pearce SC, Barrister Georgina Costello QC, Barrister Bronwyn Lincoln, Corrs Chambers Westgarth Rowena Orr QC, Barrister Paul Willee RFD QC, Barrister Minal Vohra SC, Barrister Geoffrey Dickson QC, Barrister Caroline Counsel, CC Family Lawyers John Farrell, Law Council of Australia Nazim El-Bardouh, Muslim Legal Network Melbourne* Tanja Golding, LQBTQI Legal Service David Manne, Refugee Legal Adrian Snodgrass, Fitzroy Legal Service Name Location Ella Crotty, Fitzroy Legal Service Melbourne* Alison Birchall, Domestic Violence Victoria Jennie Child, Domestic Violence Victoria Sulaika Dhanapala, -

Appendix 8: Speeches, Publications and Other Activities

APPENDIX 8: SPEECHES, PUBLICATIONS AND OTHER ACTIVITIES Tribunal members and staff undertake a wide range of activities that assist to raise awareness of the Tribunal’s role, procedures and activities. Members and staff give speeches at conferences and seminars, participate in training and education activities, publish articles and undertake other engagement activities. The record of activities for 2013–14 is in four lists: speeches and presentations; competition adjudication and training; publications; and other engagement activities. The lists in Tables A8.1, A8.2 and A8.4 are arranged by date and the list in Table A8.3 is in alphabetical order. Table A8.1 Speeches and presentations Participant/ Title/role Event/organisation speaker(s) Date The Role of the AAT Tribunal Advocacy Course, Conference 1 July 2013 Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Registrar Siobhan Ni Canberra Fhaolain Administrative Law 2013 National Administrative Law Justice Duncan Kerr, 19 July 2013 in an Interconnected Conference, Australian Institute President World: Where to from of Administrative Law, Canberra here? After the Shooting Biennial Member and Staff Justice Duncan Kerr, 7 August 2013 Stops Conference, Veterans’ Review President Board, Brisbane Diagnosing Psychiatric Biennial Member and Staff Member Dr Marian 7 August 2013 Disorders Conference, Veterans’ Review Sullivan Board, Brisbane Appraisal including Claims Assessment and Senior Member 14 August 2013 Peer Review Resolution Service, NSW Motor Bernard McCabe Accidents Authority, Sydney Keeping the AAT from