Spring 2003 Newsletter of the Delaware Estuary Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Festival of Fountains May 9 Through September 29, 2019

Longwood Gardens’ Festival of Fountains May 9 through September 29, 2019. Fountains dance and soar up to 175 feet and Illuminated Fountain Performances take 2019 SE ASONAL center stage on Thursday HIGHLIGHTS through Saturday evenings. AND MA P #BrandywineValley Six spectacular evenings when fireworks light the skies above Longwood Gardens: May 26, July 3, July 20, August 10, September 1 and September 28 Costiming THE CROWN March 30, 2019–January 5th, 2020 • Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library Evening events call for local accommodations, so plan today as rooms and tickets go quickly. Visit BrandywineValley.com. SEASONAL HIGHLIGHTS Visitors to the Brandywine Valley appreciate the unique attractions Learn about all of Chester County’s and lively annual events that take place throughout the rolling hills events by visiting: of our charming destination in the countryside of Philadelphia. BrandywineValley.com/events Events listed are for 2019, and most are held annually. SPRING SUMMER AUTUMN WINTER The season launches a Skies fill with balloons, Adventures feature Holiday magic and a slate of world-class helicopters, and fireworks, mushrooms, pumpkins, and wonderland of orchids equestrian events, a and The Blob makes an a thousand-bloom mum, all highlight this sparkling vibrant art scene, and a annual visit to Phoenixville’s set against fall's spectacular season. blooming landscape. Colonial Theatre! color palate. May 5 May 9 – Sept. 29 Sept. 7 & 8 Nov. 23 Winterthur Point-to-Point Festival of Fountains, Mushroom Festival Christmas at Nemours through Dec. 29 May 12 Longwood Gardens Sept. 28 The Willowdale June 16 Bike the Brandywine Holidays at Hagley Steeplechase Fatherfest, American Oct. -

State of the Schuylkill River Watershed

A Report on the S TATE OF THE SCHUYLKILL RIVER W ATERSHED 2002 Prepared by The Conservation Fund for the Schuylkill River Watershed Initiative T ABLE OF CONTENTS L IST OF FIGURES Forward ............................................................. 1 4. Public Awareness and Education 1 ...... Regional Location 2 ...... Physiographic Regions Introduction ....................................................... 2 Overview ........................................................... 27 3 ...... Percentage of Stream Miles by Stream 4 ...... Dams in the Schuylkill Watershed Enhancing Public Awareness ............................... 28 5 ...... Land Cover 1. The Watershed Today Educating the Next Generation .......................... 29 6 ...... 1990-2000 Population Change, by Municipality 7 ...... Land Development Trends, Montgomery County Overview ........................................................... 3 Environmental Education Centers ...................... 30 8 ...... 1970-95 Trends in Population and Land Consumption, Environmental Setting ........................................ 4 Special Recognition of the Schuylkill ................. 31 Montgomery County 9 ...... Water Supply Intakes Historical Influences ........................................... 5 10 .... Seasonal Relationships Between Water Withdrawals and River Flow 11 .... Water Withdrawals in the Schuylkill Watershed Land Use and Population Change....................... 6 5. Looking Out for the Watershed - Who is Involved 12 .... Monitoring Locations and Tributaries Surveyed -

2.0 the Planning Alternatives

2.0 THE PLANNING ALTERNATIVES LIVING WITH THE RIVER: Schuylkill River Valley National Heritage Area LIVING WITH THE RIVER: Schuylkill River Valley National Heritage Area Final Management Plan and Environmental Impact Statement Final Management Plan and Environmental Impact Statement 2.0 THE PLANNING ALTERNATIVES 2.1 ALTERNATIVES CONSIDERED The planning process included consideration of a range of alternatives for the future management of the Schuylkill River Valley National Heritage Area. Four alternatives were developed and evaluated for their Alternatives Considered performance in meeting the mission and goals set forth in Section 1.3: the No Action Alternative (A) and three Action Alternatives (B, C, and • A: No Action D). The evaluation was based on the varying emphases placed by the alternatives on the 13 strategies presented in Section 1.3 to achieve the • B: Places mission and goals (Table 2-1). • C: Experiences As part of the planning process, a series of public meetings was • D: Layers (Preferred and conducted at which the alternatives were presented for review. Based Environmentally upon the evaluation of the alternatives and public comment, Alternative Preferred Alternative) D (Layers) was selected as the Preferred Alternative developed into the recommended plan described in Section 2.2. 2.1.1 Alternative A: No Action Alternative A does not propose any change to the current operation and management of the Schuylkill River Valley National Heritage Area. Although the Schuylkill River Valley has been designated as a National Heritage Area, current programs and levels of funding would continue to be administered by SRGA and no additional funding would be provided. -

P Ennsylvania Forests

Pennsylvania Forests QUARTERLY MAGAZINE OF THE PENNSYLVANIA FORESTRY ASSOCIATION Volume 111 Number 1 Spring 2020 quarterly magazine of the pennsylvania forestry association YOUR Forest Landowner Pennsylvania forests LOCAL VOLUME 111 | NUMBER 1 MISSION STATEMENT The Pennsylvania Forestry Association is a broad-based citizen’s organization that provides leadership and LINK Associations education in sound, science-based forest management; we promote stewardship to ensure the sustainability of all forest resources, resulting in benefits for all, today and into the future. Joining a local association dedicated to forest stewardship is an excellent way to become involved in sustaining Pennsylvania’s forest COVER resources. Currently, nearly 1,000 people are members of the 21 local associations involved in forest stewardship in Pennsylvania. While a Money Rocks County Park spans over 300 acres of woodland in the Welsh majority of members own forestland, most groups do not require land ownership. Mountains of eastern Lancaster County. The pride of the park is a rocky spine of boulders called Money Rocks, so-named because farmers in the Pequea Valley The objective of most Forest Landowner Associations is to provide educational opportunities for members. Although each group is allegedly hid cash among the rocks. The ridge offers beautiful views of farmland, independent, and missions and membership policies differ, most use meetings, field demonstrations, tours, seminars and newsletters to towns, and distant wooded hills with spectacular lines of boulders. The rocks provide information about forests and sound forest management to their members and people in the local communities. are patched with lichens, mosses, and ferns. Black birch trees dominate the surrounding woodland with a thick understory of mountain laurel. -

Grant Awarded for Trail Improvements

INSIDE Summer 2008 Daniel Boone Homestead Schuylkill River Sojourn Summer Camps Trail Updates Grant Awarded For Trail Improvements Reviewing the outcome of the initial William Penn Foundation’s grant are L-R: Kara Wilson, Bob Folwell-SRHA; Andy Johnson, Feather Houstoun, Diane Schrauth of William Penn; SRHA Executive Director Kurt Zwikl. The Schuylkill River Heritage Area invaluable recreational amenity for many, has received a two-year, $735,000 and fast becoming a much needed route for grant from the Philadelphia-based pedestrian and cycling commuters.” William Penn Foundation to The trail, when complete, will run the improve the Schuylkill River Trail. entire length of the river from Philadelphia The money will fund projects that to Pottsville, totaling about 130 miles and enhance accessibility, management traversing through fi ve counties. It has been and stewardship of the trail. under construction for many years, but its various parts are owned and maintained by a The award is essentially an extension number of public and private agencies. of an earlier grant received by the SRHA in 2006. That grant, totaling Among the new projects to be undertaken $660,000, also supported Schuylkill River is the introduction this summer of a trail Trail projects. ambassador pilot program, fabrication and installation of signs and trailheads for a Funding from the new grant will go toward proposed Chester County segment of the expanding a signage system to better mark trail, and signage for a 20-mile Reading- the trail, developing a promotional program, to-Hamburg piece, much of which will be and coordinating implementation of a uniform on-road initially. -

2018 Budget Inquiries Regarding the 2018 Budget Or Requests for Copies Should Be Directed To

Chester County, Pennsylvania 2018 Budget Inquiries regarding the 2018 Budget or requests for copies should be directed to: COUNTY OF CHESTER FINANCE DEPARTMENT 313 W. MARKET STREET, SUITE 6902 P.O. BOX 2748 WEST CHESTER, PENNSYLVANIA 19380-0991 Phone: (610) 344 - 6190 Fax: (610) 344 - 5998 Web Page: http://www.chesco.org The Government Finance Officers Association of the United States and Canada (GFOA) presented a Distinguished Budget Presentation Award to the County of Chester, Pennsylva- nia for its annual budget for the fiscal year beginning January 1, 2017. In order to receive this award, a governmental unit must publish a budget document that meets program criteria as a policy document, as an operations guide, as a financial plan, and as a communications device. The award is valid for a period of one year only. We believe our current budget continues to conform to program requirements and we are submitting it to GFOA to determine its eligibil- ity for another award. QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE The following guide should assist the reader with answering some of the common questions concerning the 2018 County of Chester budget. To answer these questions... Refer to... Page... Why is the budget adopted by Fund? A Reader’s Guide to the Budget 14 What are the major issues and initiatives for the 2018 budget? Letter of Transmittal viii How will the real estate tax affect me as a homeowner? Real Estate Tax Facts 328 What is the budget development process? Budget Process 50 What is the basis of budgeting? Budget Process 51 What are the County’s -

September 11, 2010 (Pages 5119-5282)

Pennsylvania Bulletin Volume 40 (2010) Repository 9-11-2010 September 11, 2010 (Pages 5119-5282) Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2010 Recommended Citation Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, "September 11, 2010 (Pages 5119-5282)" (2010). Volume 40 (2010). 37. https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2010/37 This September is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Bulletin Repository at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 40 (2010) by an authorized administrator of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Volume 40 Number 37 Saturday, September 11, 2010 • Harrisburg, PA Pages 5119—5282 Agencies in this issue The Courts Bureau of Professional and Occupational Affairs Department of Agriculture Department of Banking Department of Environmental Protection Department of Health Department of Labor and Industry Department of Revenue Department of Transportation Environmental Quality Board Independent Regulatory Review Commission Insurance Department Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission Philadelphia Regional Port Authority State Board of Cosmetology State Board of Dentistry State Board of Medicine State Board of Nursing State Board of Vehicle Manufactures, Dealers and Salespersons State Charter School Appeal Board State Conservation Commission State Real Estate Commission -

Schuylkill River Hydrology and Consumptive Use Report Produced

Schuylkill River Hydrology and Consumptive Use Blue Marsh Reservoir, Berks County, PA Report Produced by the City of Philadelphia Water Department March 2010 This page left intentionally blank Executive Summary PWD Objective The Philadelphia Water Department’s (PWD) Source Water Protection Program is responsible for tracking and analyzing trends in water quantity and quality of the two sources of drinking water for the City of Philadelphia. A critical part of the program’s water quantity focus is to investigate the current and future water use patterns, how climate change may influence the drinking water supply, and what the balance is between the needs of the power sector, drinking water supply, aquatic communities, and recreational interests. Ultimately, PWD needs to know how upstream consumptive use impacts drinking water availability to the City of Philadelphia. In order to prioritize research and study interests to obtain this information, there are two critical questions that PWD addresses in this analysis: Is there enough water to meet current needs? What are the current competing water needs in the Schuylkill River? By answering these questions, the Schuylkill River Hydrology and Consumptive Use Analysis is a first step towards identifying the factors that influence the quantity of drinking water available to Philadelphia from the Schuylkill River. Preliminary observations of consumptive use and hydrology are made, and critical future studies are identified. The work presented here builds upon work done by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PADEP) in the Act 220 studies because it focuses solely on the Schuylkill River as a drinking water supply to Philadelphia. -

An Annotated List of Cumberland County Birds Upated 2016

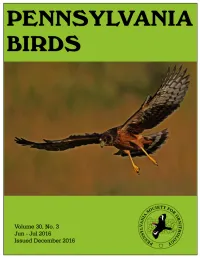

PENNSYLVANIA BIRDS Seasonal Editors Journal of the Pennsylvania Society for Ornithology Daniel Brauning Michael Fialkovich Volume 30 Number 3 Jun 2016 - Jul 2016 Nick Bolgiano Geoff Malosh Greg Grove, Editor-in-chief 9524 Stone Creek Ridge Road Department Editors Huntingdon, PA 16652 Book Reviews (814) 643 3295 [email protected] Gene Wilhelm, Ph.D. 513 Kelly Blvd. http://www.pabirds.org Slippery Rock, PA 16057-1145 (724) 794-2434 [email protected] CBC Report Nick Bolgiano 711 W. Foster Ave. Contents State College, PA 16801 (814) 234-2746 [email protected] 135 from the Editor Haw k Watch Reports Laurie Goodrich Keith Bildstein 136 First confirmed breeding record of Virginia Rail in 410 Summer Valley Rd. Orw igsburg, PA 17961 Allegheny County . Geoff Malosh (570) 943-3411 goodrich@haw kmtn.org [email protected] 138 Annotated List of Cumberland County Birds . Vern Gauthier PAMC Chuck Berthoud 4461 Cherry Drive 148 Book Review: Waterfowl of North America, Europe, and Asia Spring Grove, PA 17362 . Gene Wilheim [email protected] Franklin Haas 2469 Hammertow n Road 150 Summary of the Season: Summer 2016 . Dan Brauning Narvon, PA 17555 [email protected] 153 Suggestions for Contributors – Publication Schedule Pennsylvania Birdlists Peter Robinson P. O. Box 482 Hanover, PA 17331 154 Birds of Note – June through July 2016 [email protected] Data Technician 157 Photographic Highlights Wendy Jo Shemansky 41 Walkertow n Hill Rd. Daisytow n, PA 15427 162 Local Notes – Summer 2016 [email protected] Publication Manager Franklin Haas Inside back cover – In Focus 2469 Hammertow n Rd. Narvon, PA 17555 [email protected] Photo Editor Ted Nichols II 102 Spruce Ct. -

Fall-Winter 2012

S t r e a S t r e a m l i n e s Volume 48 Issue 4 from Green Valleys Association at Welkinweir Fall/Winter 2012 GVA’s Watershed Assessment Program Martin Challenge In order to develop a good assessment of a watershed’s health status, we need to We have received a $25,000 challenge collect data of different kinds. And, since water quality varies significantly from stream grant from the George and Miriam Mar- to stream we need to do it at many places throughout the watershed. tin Foundation in support of our watershed programs. Please take advantage of the There are many kinds of data we can collect and use as indicators of the health of a Martin Challenge and support GVA and watershed. GVA is currently collecting four of these: the enduring work we are doing for our 1. In the stream: Chemical and Microbiological Water Quality Data beautiful Chester County Watersheds, by 2. In the stream: Indexes of Biotic Integrity (IBIs). making a special gift to Green Valleys. 3. In and along the stream: Habitat Assessments (HAs) 4. Along the stream and throughout the watershed: Land Cover Each watershed typically is made up of many waterways. For example, the Pickering Creek Watershed is 38.8 square miles. Within it is the main stem of the Pickering Creek, plus there are additional named streams—such as Pigeon Run—that are tribu- taries to the Pickering. As mentioned above, water quality data and other indicators vary significantly from stream to stream, making it necessary to define smaller study areas called subwatersheds. -

334.8 224.2 102.6 3148.0 338.7Militia22.4 Hill 199993.9 6792.6 1578.8 0.7 76.7 181.1 98.5 41.3 0.0 99.5 13693.3

Seasonal Editors PENNSYLVANIA BIRDS Daniel Brauning Journal of the Pennsylvania Society for Ornithology Michael Fialkovich Nick Bolgiano Volume 33 Number 4 August - November 2019 Geoff Malosh Greg Grove, Editor-in-chief Department Editors 9524 Stone Creek Ridge Road Book Reviews Huntingdon, PA 16652 Gene Wilhelm, Ph.D. 513 Kelly Blvd. (814) 643 3295 [email protected] Slippery Rock, PA https://pabirds.org 16057-1145 (724) 794-2434 [email protected] Contents CBC Report Nick Bolgiano 711 W. Foster Ave. 213 from the Editor State College, PA 16801 (814) 234-2746 [email protected] 214 Barbara Haas Hawk Watch Reports 21 6 Twenty-fifth Report of the Pennsylvania Ornithological Records David Barber 410 Summer Valley Rd. Committee 2018 Records...........................................Mike Fialkovich Orwigsburg, PA 17961 (570) 943-3411 [email protected] 222 American Kestrel nest box numbers from 2019 Data Technician 22 3 The Identification of the Burket Triple Hybrid — A Wendy Jo Shemansky 41 Walkertown Hill Rd. Brewster's/Chestnut-sided Warbler.......................Deborah S. Grove Daisytown, PA 15427 [email protected] 226 Merlin: Expansion of Breeding Range into Pennsylvania................... Publication Manager . .....................................................................................Robert Snyder Franklin Haas 2469 Hammertown Rd. Narvon, PA 17555 230 Pennsylvania Autumn Raptor Migration Summary 2019..................... [email protected] ...................................................................................David -

NOTICES DEPARTMENT of BANKING Action on Applications

2927 NOTICES DEPARTMENT OF BANKING Action on Applications The Department of Banking, under the authority contained in the act of November 30, 1965 (P. L. 847, No. 356), known as the Banking Code of 1965; the act of December 14, 1967 (P. L. 746, No. 345), known as the Savings Association Code of 1967; the act of May 15, 1933 (P. L. 565, No. 111), known as the Department of Banking Code; and the act of December 19, 1990 (P. L. 834, No. 198), known as the Credit Union Code, has taken the following action on applications received for the week ending May 25, 2004. BANKING INSTITUTIONS Holding Company Acquisitions Date Name of Corporation Location Action 5-14-04 Community Bank System, Inc., DeWitt, NY Effective DeWitt, NY, acquired 100% of the voting shares of First Heritage Bank, Wilkes-Barre, PA Note: Subsequent to the acquisition, First Heritage Bank was merged with and into Community Bank, National Association, Canton, NY, and ceased to be regulated by the Department of Banking. 5-24-04 First Commonwealth Financial Indiana Effective Corporation, IN, acquired 100% of the voting shares of GA Financial, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA Consolidations, Mergers and Absorptions Date Name of Bank Location Action 5-24-04 First Commonwealth Bank, Indiana Effective IN, and Great American Federal, Pittsburgh, PA Surviving Institution— First Commonwealth Bank, IN Branches Acquired Via Merger: 548 Rock Run Road 4750 Clairton Boulevard Buena Vista Pittsburgh Allegheny County Allegheny County 608 Miller Avenue Baptist and Grove Roads Clairton Pittsburgh Allegheny County Allegheny County 2210 Ardmore Boulevard 250 Summit Park Drive Forest Hills Pittsburgh Allegheny County Allegheny County 500 East Waterfront Drive 1105 South Braddock Avenue Homestead Pittsburgh Allegheny County Allegheny County 225 5th Avenue 6015 Mountain View Drive McKeesport West Mifflin Allegheny County Allegheny County 4600 Main Street 1527 Lincoln Way Munhall White Oak Allegheny County Allegheny County PENNSYLVANIA BULLETIN, VOL.