“Words About Wen-Chung: Concentric Connections” Thoughts After His Passing … by Roger Reynolds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Italians of the South Village

The Italians of the South Village Report by: Mary Elizabeth Brown, Ph.D. Edited by: Rafaele Fierro, Ph.D. Commissioned by: the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 E. 11th Street, New York, NY 10003 ♦ 212‐475‐9585 ♦ www.gvshp.org Funded by: The J.M. Kaplan Fund Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 East 11th Street, New York, NY 10003 212‐475‐9585 212‐475‐9582 Fax www.gvshp.org [email protected] Board of Trustees: Mary Ann Arisman, President Arthur Levin, Vice President Linda Yowell, Vice President Katherine Schoonover, Secretary/Treasurer John Bacon Penelope Bareau Meredith Bergmann Elizabeth Ely Jo Hamilton Thomas Harney Leslie S. Mason Ruth McCoy Florent Morellet Peter Mullan Andrew S. Paul Cynthia Penney Jonathan Russo Judith Stonehill Arbie Thalacker Fred Wistow F. Anthony Zunino III Staff: Andrew Berman, Executive Director Melissa Baldock, Director of Preservation and Research Sheryl Woodruff, Director of Operations Drew Durniak, Director of Administration Kailin Husayko, Program Associate Cover Photo: Marjory Collins photograph, 1943. “Italian‐Americans leaving the church of Our Lady of Pompeii at Bleecker and Carmine Streets, on New Year’s Day.” Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Reproduction Number LC‐USW3‐013065‐E) The Italians of the South Village Report by: Mary Elizabeth Brown, Ph.D. Edited by: Rafaele Fierro, Ph.D. Commissioned by: the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 E. 11th Street, New York, NY 10003 ♦ 212‐475‐9585 ♦ www.gvshp.org Funded by: The J.M. Kaplan Fund Published October, 2007, by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation Foreword In the 2000 census, more New York City and State residents listed Italy as their country of ancestry than any other, and more of the estimated 5.3 million Italians who immigrated to the United States over the last two centuries came through New York City than any other port of entry. -

Inside Greenwich Village: a New York City Neighborhood, 1898-1918 Gerald W

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst University of Massachusetts rP ess Books University of Massachusetts rP ess 2001 Inside Greenwich Village: A New York City Neighborhood, 1898-1918 Gerald W. McFarland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/umpress_books Part of the History Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation McFarland, Gerald W., "Inside Greenwich Village: A New York City Neighborhood, 1898-1918" (2001). University of Massachusetts Press Books. 3. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/umpress_books/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Massachusetts rP ess at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Massachusetts rP ess Books by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Inside Greenwich Village This page intentionally left blank Inside Greenwich Village A NEW YORK CITY NEIGHBORHOOD, 1898–1918 Gerald W. McFarland University of Massachusetts Press amherst Copyright ᭧ 2001 by University of Massachusetts Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America LC 00-054393 ISBN 1–55849-299–2 Designed by Jack Harrison Set in Janson Text with Mistral display by Graphic Composition, Inc. Printed and bound by Sheridan Books, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McFarland, Gerald W., 1938– Inside Greenwich Village : a New York City neighborhood, 1898–1918 / Gerald W. McFarland. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 1–55849-299–2 (alk. paper) 1. Greenwich Village (New York, N.Y.)—History—20th century. 2. Greenwich Village (New York, N.Y.)—Social conditions—20th century. -

Oral History Interview with Paulus Berensohn, 2009 March 20-21

Oral history interview with Paulus Berensohn, 2009 March 20-21 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project For Craft and Decorative Arts in America The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Paulus Berensohn on 2009 March 20 and 21. The interview took place at Berensohn's home in Penland, North Carolina, and was conducted by Mark Shapiro for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Berensohn has reviewed the transcript and has made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MARK SHAPIRO: I'm here in Paulus' home in Penland, North Carolina, and it's March 19th? PAULUS BERENSOHN: Nineteenth [20], and it's the vernal equinox— MR. SHAPIRO: Perfect. MR. BERENSOHN: Which is propitious. MR. SHAPIRO: Very propitious. MR. BERENSOHN: At 11:44 exactly it will be the vernal equinox when the ewes are born. MR. SHAPIRO: And this is the first disk, the first card. So Paulus, will you tell us a little bit about where you were born and the circumstances of you coming into the world? MR. BERENSOHN: Oh, my goodness. I was born in New York City. -

Programs and Services Arts and Education

PROGRAMS AND SERVICES ARTS AND EDUCATION Greenwich House Music: A center for artistic education and expression that provides music instruction for youth and adults, dance and visual art programs for children, concerts, workshops and music education outreach to public schools. Greenwich House Pottery: A full service ceramics studio and gallery offering classes for all ages, workshops, fabrications, residencies, intern programs and solo and group exhibitions. After-School and Summer Arts Camp: An arts program that provides children ages 5-17 (Summer Camp 7-14) quality, affordable educational programming that encourages creativity and builds self-esteem. Includes Greenwich House Girls Basketball, a non- competitive league for girls ages 9-15. Barrow Street Nursery School: A private education and childcare program that features service-oriented curriculum with half and full-day sessions with flexible schedules. SENIOR SERVICES Senior Centers: Four senior centers in lower Manhattan provide daily hot meals and cultural, recreational and wellness activities and classes. Senior Health & Consultation Center: Only program in Greenwich Village that provides quality mental health services to persons 6o years of age and older, including home visits. Case Management and Daily Money Management: Licensed social workers provide a full range of case management services including assistance with benefits, entitlements, housing issues and money management. BEHAVIORAL HEALTH Children’s Safety Project: A treatment and prevention program for children and families, enabling them to overcome the impact of trauma. Therapists offer specialized treatment for clients from preschool through age 21. Chemical Dependency Program: An outpatient clinic that provides diagnosis, treatment and medically supervised drug-free counseling to people struggling with substance abuse, along with support for their families. -

Peter Jarvis, Director

The 2012-2013 Season is dedicated to Elliott Carter. The Concert Tonight is dedicated to John Korchok Founder and Director of Experimental Musicians New Jersey. Program Inventions on a Motive (1955) Michael Colgrass for Percussion Quartet Motive Invention 1 Invention 2 The William Paterson University Invention 3 Invention 4 Invention 5 presents Invention 6 Finale John Henry Bishop, Travis Salem, Kiana Salameh, Dakota Singerline Peter Jarvis - Conductor New Music Series Out of Frame (2012) James Romig Peter Jarvis, director For Three Marimba Players Tim Malone, Steve Nowakowski & David Endean John Ferrari – Conductor with guests Without a Doubt (2009) * Dominic Donato Lynn Bechtold, Dan Cooper For Solo Drum Set and Peter Jarvis Gene Pritsker Inside (2006) Gene Pritsker For Electronic Sounds Invention 2 (2006) Daniel Levitan For Percussion Duo Monday, April 1, 2013, 7:00 PM Patrick Lapinski & Mike Jacquot Peter Jarvis - Coach Shea Center for the Performing Arts Paroxysm Extract (2012) Gene Pritsker For Electronic Sounds The Frame Problem (2003) James Romig For Percussion Trio Tim Malone, Steve Nowakowski & David Endean Payton MacDonald - Conductor Invention 2: Daniel Levitan Red Eye (2012) * Evan Hause Invention 2 is a short percussion duos in which the choices of instrumentation, Trio for Guitar, Bass and Drums tempo, and dynamics are left to the performers. The musical interest lies is the interplay Dan Cooper, Peter Jarvis & Gene Pritsker of rhythms between the two players, so that the pieces should be immediately recognizable no matter which instruments are used. Paroxysm Extract: Gene Pritsker Controlled Improvisation Number 2 (2012) Peter Jarvis I wrote Paroxysm as a commission for a dance piece by Erin Bomboy . -

Battle on Barrow Street—

The Voice of the West Village WestView News VOLUME 14, NUMBER 8 AUGUST 2018 $1.00 eration is in the basement and their elevator Battle on Barrow Street— is inadequate; it requires an operator, who I, personally, have never seen and only fits one City Awards A Victory for Organized Villagers person at a time in it. I don’t even know if wheelchairs will fit. By Jane Heil Usyk So a lot of regulars will have to stop com- WestView ing. Second, there are no walls in the base- Well! It has been quite a week; several ment of Pompeii, meaning there will be no $5000 meetings, two demonstrations, petition more movies, no activities, nothing that signing, and who knows what next week. requires its own space. Third, they do not Erik Botcher, the Chief of Staff for Here is how it played out: on Monday, July have a complete kitchen at Pompeii, and City Council Speaker, Corey John- 9th, I went to the senior center, Greenwich they have all their meals delivered from out- son, called George Capsis, the pub- House, at 27 Barrow Street to see “The Big side, unlike Barrow Street, which has a full, lisher of WestView News, to say the Knife,” one of the many excellent films that working kitchen and excellent, large meals City had awarded the paper an un- show every Monday and Wednesday, se- that come out of it. precedented grant of $5000 to sup- lected by Anthony Cilione, the director of Afterward, the person next to me verified port its enormously popular Free the Barrow Street senior center. -

Ceramics Now Jane Hartsook Gallery’S 2013 Exhibition Series Pottery

CERAMICS NOW JANE HARTSOOK GALLERY’S 2013 EXHIBITION SERIES POTTERY EXHIBITIONS Josh DeWeese, January 17 – February 14, 2013 HOUSE Jessica Stoller & Robert Raphael, February 28 – March 26, 2013 Steven Lee, April 11 – May 9, 2013 Christopher Adams, July 11 – August 8, 2013 Linda Lopez, October 25 – November 21, 2013 Kirk Mangus & Sebastian Moh, December 5, 2013 – January 3, 2014 GREENWICH JANE HARTSOOK GALLERY AT GREENWICH HOUSE POTTERY COPYRIGHT CERAMICS NOW ADAM WELCH The mood of the artworld has found expression in clay. The groundswell of interest in ceramics now taking place is unprecedented and New York City is the epicenter. As director of Greenwich House Pottery, I have the privilege of witnessing this phenomenon firsthand. In addition to the numerous gallery and museum exhibitions around the city, our studios are filled with artists looking to expand their artistic practice. From Joanne Greenbaum to Ghada Amer, Pam Lins to David Salle, artists are exploiting clay’s expressive potential and have found a welcoming home in our studios. Whether making work for an upcoming solo exhibition in their respective galleries, or developing ideas for the Whitney Biennial, their activityPOTTERY has added to the culture, community and undoubtedly to the discourse of the field. Greenwich House Pottery is not an isolated example. Ceramics is gaining momentum coast-to-coast and our This catalog, “Ceramics Now”, was published in conjunction with the “Ceramics Now” exhibition series held at Greenwich House studio, members, and the entirety of the ceramics sphere are the beneficiaries. I believe the influx of “outsider” Pottery’s Jane Hartsook Gallery from January 2013 – January 2014. -

Musical Numbers Act One

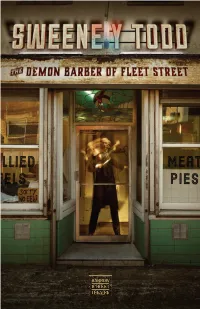

Harrington’s Pie and Mash Shop 3 Selkirk Road Tooting, London. Open for business since 1908. “A Customer!” My name is Rachel Edwards and I am the originating producer of Tooting Arts Club’s Sweeney Todd. On behalf of myself, and my producing partners Jenny Gersten, Greg Nobile, Jana Shea and Nate Koch, it is our pleasure to welcome you to Harrington’s Pie and Mash Shop! In the spring of 1908, number 3 Selkirk Road Tooting, London, became the home of Harrington’s Pie and Mash shop when it was bought by Bertie Harrington and his wife Clara. Little has changed in this tiny Tooting eatery since it first opened for business some 109 years ago. The Harrington fam- ily still run the shop, the original green tiles still adorn the walls and the menu remains unchanged since the days of Queen Victoria. The idea to stage Sweeney Todd in London’s oldest pie and mash shop was one which I lived with for several years before I dared to say it out loud. It felt too outrageous, too complicated, in essence – it felt impossible. A simple ‘yes’ from Beverley Mason – owner of Harrington’s, and great grand-daughter of Bertie and Clara – changed everything. Subsequently, an unforgettable collabora- tion was born that set in motion a chain of events that was nothing short of extraordinary. Nothing was ever a problem ‘Can we replace your fridge with a piano?’ Of course you can. ‘Stand on your counter?’ Go ahead. ‘Sorry about the blood!’ Don’t worry about it. This generosity, coupled with the sheer skill and enthusiasm of the creative team, our pie-shop Sweeney began to take shape. -

“An Anatomy of Modernism”: Marion Rous and “What Next in Music?”

"An Anatomy of Modernism": Marion Rous and "What Next in Music?" Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Skoronski, Benjamin Patrick Citation Skoronski, Benjamin Patrick. (2021). "An Anatomy of Modernism": Marion Rous and "What Next in Music?" (Master's thesis, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA). Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 07:40:08 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/660260 “AN ANATOMY OF MODERNISM”: MARION ROUS AND “WHAT NEXT IN MUSIC?” by Benjamin Patrick Skoronski _____________________ Copyright © Benjamin Patrick Skoronski 2021 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2021 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Master’s Committee, we certify that we have read the thesis prepared by: Benjamin Patrick Skoronski titled: and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the thesis requirement for the Master’s Degree. Matthew S Mugmon _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________May 12, 2021 Matthew S Mugmon _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________May 12, 2021 Jay Rosenblatt John T. Brobeck _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________May 12, 2021 John T. Brobeck Final approval and acceptance of this thesis is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the thesis to the Graduate College. -

Download The

SENIOR Resource Guide Assemblymember Deborah J. Glick TABLE OF CONTENTS Housing • Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption (SCRIE) ................................ 4 • MFY Legal Services .............................................................................. 4 • Metropolitan Council on Housing ....................................................... 4 • Senior Citizens Homeowners Exemption (SCHE) ................................ 4 • The Home Energy Assistance Program (HEAP) ................................... 5 • The New York State Division of Housing and Community Renewal (HCR) ............................................................... 5 • Podell and Weinberg Senior Housing ................................................... 5 • Con Edison Senior Direct Program ...................................................... 5 • Con Edison CONCERN Program ....................................................... 6 Senior Centers • Greenwich House Locations ................................................................. 7 • Battery Park City Seniors ...................................................................... 7 • Manhattan Youth Downtown Community Center ............................... 8 • Sirovich Center for Balanced Living ..................................................... 8 Health Services • Visiting Neighbors ............................................................................... 9 • Home Health Aides .............................................................................. 9 • Andrew Heiskell Library ...................................................................... -

Diller Island Is Dead Your Own Concert Hall by George Capsis Mer Head of Paramount, Barry Diller, Per- Haps in a Moment of Terminal Pique, to Say, at 7:00 A.M

The Voice of the West Village WestView News VOLUME 13, NUMBER 10 OCTOBER 2017 $1.00 Diller Island is Dead Your Own Concert Hall By George Capsis mer head of Paramount, Barry Diller, per- haps in a moment of terminal pique, to say, At 7:00 a.m. on September 22nd, I “The hell with it, I’m out of here!” came out of the shower to a ringing This came as a surprise to everybody in- phone and stood, still dripping, as West- cluding the members of The City Club’s View contributor Barbara Chacour an- President, attorney Michael Gruen, and nounced with exhilaration, “Diller Island former head of the Hudson River Park is Dead.” These were the very words Trust (HRPT), Tom Fox, who were hours printed on the front page of the New York away from presenting a compromise. They Times article by Charles V. Bagli who, I were going to let the island proceed if suspect, went to P.S. 41 with my kids. Diller and/or the HRPT would recreate Wow, Diller Island Dead. You can go a beach shoreline at Pier 79 (Gansevoort through a lifetime without a victory like Street) and restore a pier for historic ships. this but it was not my victory or WestView’s What motivated 73-year-old Durst to “MY ENTHUSIASTIC SUPPORT”: Father Santiago Rubio has given his “enthusiastic sup- port” to opening the doors of St. Veronica’s and turning it into a concert hall. Success depends on the attendance at the Saturday, November 25th and Christmas concerts. -

Greenwich House Pottery

Greenwich house pottery NOT FOR RESALE GREENWICHEDUCATIONAL HOUSE USE POTTERY ONLY HANDBOOK 2020 I'M eternally “grateful that i still have the strong desire to work with clay and that Greenwich House Pottery exists whereNOT FOR i RESALEaND so many EDUCATIONALothers USE ONLY “ haveGREENWICH found HOUSE POTTERY a precious haven. Lilli Miller, Student since the early 1950s Greenwich House Pottery 2020 HANDBOOK NOT FOR RESALE GREENWICHEDUCATIONAL HOUSE USE POTTERY ONLY Greenwich House Pottery 16 Jones Street New York, New York 10014 Phone: 212-242-4106 Email: [email protected] Web: greenwichhousepottery.org facebook.com/greenwichhousepottery facebook.com/janehartsookgallery instagram.com/greenwichhousepottery instagram.com/janehartsook twitter.com/ghpottery artsy.net/jane-hartsook-gallery Book Design by Adam Welch Text by Adam Welch Edited by Lisa Chicoyne, Jenni Lukasiewicz, Kaitlin McClure, Adam Welch Greenwich House Pottery Executive Staff Adam Welch, Director Jenni Lukasiewicz, Education & Events Manager Kaitlin McClure, Gallery & Residency Manager Anjuli Wright, Interim Studio Manager Greenwich House Inc. Executive Staff Darren S. Bloch, Chief Executive Officer Janet Ross, Chief Financial OfficerNOT FOR RESALE Andrea Newman, Assistant Executive Director Development, Public Relations & Communications Greenwich House Board of Directors Jan-Willem van den Dorpel, Chair Christine Grygiel West, Vice-Chair Christopher Kiplok, Vice-ChairGREENWICHEDUCATIONAL HOUSE USE POTTERY ONLY Samir Hussein, Treasurer Cathy Aquila, Secretary Edward