Desertification, Land Degradation and Drought: a Complex Nexus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Degradation Neutrality

Land Degradation Neutrality: implications and opportunities for conservation Nature Based Solutions to Desertification, Land Degradation and Drought 2nd Edition, November 2015 IUCN Global Drylands Initiative Land Degradation Neutrality: implications and opportunities for conservation Nature Based Solutions to Desertification, Land Degradation and Drought 2nd Edition, November 2015 With contributions from Global Drylands Initiative, CEM, WCEL, WCPA, CEC1 1 Contributors: Jonathan Davies, Masumi Gudka, Peter Laban, Graciela Metternicht, Sasha Alexander, Ian Hannam, Leigh Welling, Liette Vasseur, Jackie Siles, Lorena Aguilar, Lene Poulsen, Mike Jones, Louisa Nakanuku-Diggs, Julianne Zeidler, Frits Hesselink Copyright: ©2015 IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, Global Drylands Initiative, CEM, WCEL, WCPA and CEC. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN and CEM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN,Global Drylands Initiative, CEM, WCEL, WCPA and CEC. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage -

Global Environmental Issues and Its Remedies

International Journal of Sustainable Energy and Environment Vol. 1, No. 8, September 2013, PP: 120 - 126, ISSN: 2327- 0330 (Online) Available online at www.ijsee.com Research article Global Environmental Issues and its Remedies Dr. MD. Zulfequar Ahmad Khan* Address Present. Permanent Address for Correspondence *Dr. Md Zulfequar Ahmad Khan 21-B, Lane No 3, Associate Professor Jamia Nagar, Zakir Nagar, Department of Geography & Environmental Studies New Delhi-110025 Arba Minch University INDIA Arba Minch, Ethiopia. Mobile No.: +919718502867 Mobile No: +251 923934234 E-mail: [email protected] _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract To the surprise of many out-spoken environmentalists, it, in fact, turns out mankind and technology actually aren’t the only significant causes of global environmental problems. However, before we start to get too comfortable and confidently assume that we as human beings are officially “off the hook,” the fact remains that several “man-made” causes play a significant role in our current, global problems trend. Many human actions affect what people value. One way in which the actions that cause global change are different from most of these is that the effects take decades to centuries to be realized. This fact causes many concerned people to consider taking action now to protect the values of those who might be affected by global environmental change in years to come. But because of uncertainty about how global environmental systems work, and because the people affected will probably live in circumstances very much different from those of today and may have different values, it is hard to know how present-day actions will affect them. -

Chapter 4: Land Degradation

Final Government Distribution Chapter 4: IPCC SRCCL 1 Chapter 4: Land Degradation 2 3 Coordinating Lead Authors: Lennart Olsson (Sweden), Humberto Barbosa (Brazil) 4 Lead Authors: Suruchi Bhadwal (India), Annette Cowie (Australia), Kenel Delusca (Haiti), Dulce 5 Flores-Renteria (Mexico), Kathleen Hermans (Germany), Esteban Jobbagy (Argentina), Werner Kurz 6 (Canada), Diqiang Li (China), Denis Jean Sonwa (Cameroon), Lindsay Stringer (United Kingdom) 7 Contributing Authors: Timothy Crews (The United States of America), Martin Dallimer (United 8 Kingdom), Joris Eekhout (The Netherlands), Karlheinz Erb (Italy), Eamon Haughey (Ireland), 9 Richard Houghton (The United States of America), Muhammad Mohsin Iqbal (Pakistan), Francis X. 10 Johnson (The United States of America), Woo-Kyun Lee (The Republic of Korea), John Morton 11 (United Kingdom), Felipe Garcia Oliva (Mexico), Jan Petzold (Germany), Mohammad Rahimi (Iran), 12 Florence Renou-Wilson (Ireland), Anna Tengberg (Sweden), Louis Verchot (Colombia/The United 13 States of America), Katharine Vincent (South Africa) 14 Review Editors: José Manuel Moreno Rodriguez (Spain), Carolina Vera (Argentina) 15 Chapter Scientist: Aliyu Salisu Barau (Nigeria) 16 Date of Draft: 07/08/2019 17 Subject to Copy-editing 4-1 Total pages: 186 Final Government Distribution Chapter 4: IPCC SRCCL 1 2 Table of Contents 3 Chapter 4: Land Degradation ......................................................................................................... 4-1 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

Desertification and Agriculture

BRIEFING Desertification and agriculture SUMMARY Desertification is a land degradation process that occurs in drylands. It affects the land's capacity to supply ecosystem services, such as producing food or hosting biodiversity, to mention the most well-known ones. Its drivers are related to both human activity and the climate, and depend on the specific context. More than 1 billion people in some 100 countries face some level of risk related to the effects of desertification. Climate change can further increase the risk of desertification for those regions of the world that may change into drylands for climatic reasons. Desertification is reversible, but that requires proper indicators to send out alerts about the potential risk of desertification while there is still time and scope for remedial action. However, issues related to the availability and comparability of data across various regions of the world pose big challenges when it comes to measuring and monitoring desertification processes. The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification and the UN sustainable development goals provide a global framework for assessing desertification. The 2018 World Atlas of Desertification introduced the concept of 'convergence of evidence' to identify areas where multiple pressures cause land change processes relevant to land degradation, of which desertification is a striking example. Desertification involves many environmental and socio-economic aspects. It has many causes and triggers many consequences. A major cause is unsustainable agriculture, a major consequence is the threat to food production. To fully comprehend this two-way relationship requires to understand how agriculture affects land quality, what risks land degradation poses for agricultural production and to what extent a change in agricultural practices can reverse the trend. -

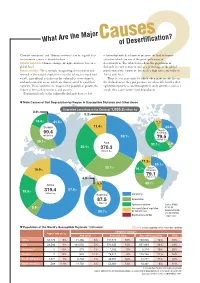

What Are the Major Causes of Desertification?

What Are the Major Causesof Desertification? ‘Climatic variations’ and ‘Human activities’ can be regarded as relationship with development pressure on land by human the two main causes of desertification. activities which are one of the principal causes of Climatic variations: Climate change, drought, moisture loss on a desertification. The table below shows the population in global level drylands by each continent and as a percentage of the global Human activities: These include overgrazing, deforestation and population of the continent. It reveals a high ratio especially in removal of the natural vegetation cover(by taking too much fuel Africa and Asia. wood), agricultural activities in the vulnerable ecosystems of There is a vicious circle by which when many people live in arid and semi-arid areas, which are thus strained beyond their the dryland areas, they put pressure on vulnerable land by their capacity. These activities are triggered by population growth, the agricultural practices and through their daily activities, and as a impact of the market economy, and poverty. result, they cause further land degradation. Population levels of the vulnerable drylands have a close 2 ▼ Main Causes of Soil Degradation by Region in Susceptible Drylands and Other Areas Degraded Land Area in the Dryland: 1,035.2 million ha 0.9% 0.3% 18.4% 41.5% 7.7 % Europe 11.4% 34.8% North 99.4 America million ha 32.1% 79.5 million ha 39.1% Asia 52.1% 5.4 26.1% 370.3 % million ha 11.5% 33.1% 30.1% South 16.9% 14.7% America 79.1 million ha 4.8% 5.5 40.7% Africa -

Land Degradation

SPM4 Land degradation Coordinating Lead Authors: Lennart Olsson (Sweden), Humberto Barbosa (Brazil) Lead Authors: Suruchi Bhadwal (India), Annette Cowie (Australia), Kenel Delusca (Haiti), Dulce Flores-Renteria (Mexico), Kathleen Hermans (Germany), Esteban Jobbagy (Argentina), Werner Kurz (Canada), Diqiang Li (China), Denis Jean Sonwa (Cameroon), Lindsay Stringer (United Kingdom) Contributing Authors: Timothy Crews (The United States of America), Martin Dallimer (United Kingdom), Joris Eekhout (The Netherlands), Karlheinz Erb (Italy), Eamon Haughey (Ireland), Richard Houghton (The United States of America), Muhammad Mohsin Iqbal (Pakistan), Francis X. Johnson (The United States of America), Woo-Kyun Lee (The Republic of Korea), John Morton (United Kingdom), Felipe Garcia Oliva (Mexico), Jan Petzold (Germany), Mohammad Rahimi (Iran), Florence Renou-Wilson (Ireland), Anna Tengberg (Sweden), Louis Verchot (Colombia/ The United States of America), Katharine Vincent (South Africa) Review Editors: José Manuel Moreno (Spain), Carolina Vera (Argentina) Chapter Scientist: Aliyu Salisu Barau (Nigeria) This chapter should be cited as: Olsson, L., H. Barbosa, S. Bhadwal, A. Cowie, K. Delusca, D. Flores-Renteria, K. Hermans, E. Jobbagy, W. Kurz, D. Li, D.J. Sonwa, L. Stringer, 2019: Land Degradation. In: Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, E. Calvo Buendia, V. Masson-Delmotte, H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, P. Zhai, R. Slade, S. Connors, R. van Diemen, M. Ferrat, E. Haughey, S. Luz, S. Neogi, M. Pathak, J. Petzold, J. Portugal Pereira, P. Vyas, E. Huntley, K. Kissick, M. Belkacemi, J. Malley, (eds.)]. In press. -

Assessing Climate Change's Contribution to Global Catastrophic

Assessing Climate Change’s Contribution to Global Catastrophic Risk Simon Beard,1,2 Lauren Holt,1 Shahar Avin,1 Asaf Tzachor,1 Luke Kemp,1,3 Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh,1,4 Phil Torres, and Haydn Belfield1 5 A growing number of people and organizations have claimed climate change is an imminent threat to human civilization and survival but there is currently no way to verify such claims. This paper considers what is already known about this risk and describes new ways of assessing it. First, it reviews existing assessments of climate change’s contribution to global catastrophic risk and their limitations. It then introduces new conceptual and evaluative tools, being developed by scholars of global catastrophic risk that could help to overcome these limitations. These connect global catastrophic risk to planetary boundary concepts, classify its key features, and place global catastrophes in a broader policy context. While not yet constituting a comprehensive risk assessment; applying these tools can yield new insights and suggest plausible models of how climate change could cause a global catastrophe. Climate Change; Global Catastrophic Risk; Planetary Boundaries; Food Security; Conflict “Understanding the long-term consequences of nuclear war is not a problem amenable to experimental verification – at least not more than once" Carl Sagan (1983) With these words, Carl Sagan opened one of the most influential papers ever written on the possibility of a global catastrophe. “Nuclear war and climatic catastrophe: Some policy implications” set out a clear and credible mechanism by which nuclear war might lead to human extinction or global civilization collapse by triggering a nuclear winter. -

Download Global Catastrophic Risks 2020

Global Catastrophic Risks 2020 Global Catastrophic Risks 2020 INTRODUCTION GLOBAL CHALLENGES FOUNDATION (GCF) ANNUAL REPORT: GCF & THOUGHT LEADERS SHARING WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ON GLOBAL CATASTROPHIC RISKS 2020 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors. Their statements are not necessarily endorsed by the affiliated organisations or the Global Challenges Foundation. ANNUAL REPORT TEAM Ulrika Westin, editor-in-chief Waldemar Ingdahl, researcher Victoria Wariaro, coordinator Weber Shandwick, creative director and graphic design. CONTRIBUTORS Kennette Benedict Senior Advisor, Bulletin of Atomic Scientists Angela Kane Senior Fellow, Vienna Centre for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation; visiting Professor, Sciences Po Paris; former High Representative for Disarmament Affairs at the United Nations Joana Castro Pereira Postdoctoral Researcher at Portuguese Institute of International Relations, NOVA University of Lisbon Philip Osano Research Fellow, Natural Resources and Ecosystems, Stockholm Environment Institute David Heymann Head and Senior Fellow, Centre on Global Health Security, Chatham House, Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Romana Kofler, United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs Lindley Johnson, NASA Planetary Defense Officer and Program Executive of the Planetary Defense Coordination Office Gerhard Drolshagen, University of Oldenburg and the European Space Agency Stephen Sparks Professor, School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol Ariel Conn Founder and -

Land Degradation and Mitigation Policies in the Mediterranean Region: a Brief Commentary

sustainability Commentary Land Degradation and Mitigation Policies in the Mediterranean Region: A Brief Commentary Rares Halbac-Cotoara-Zamfir 1 , Daniela Smiraglia 2,* , Giovanni Quaranta 3 , Rosanna Salvia 3 , Luca Salvati 4 and Antonio Giménez-Morera 5 1 Department of Overland Communication Ways, Foundation and Cadastral Survey, Politehnica University of Timisoara, 1A I. Curea Street, 300224 Timisoara, Romania; rares.halbac-cotoara-zamfi[email protected] 2 Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA), Via Vitaliano Brancati 48, I-00144 Rome, Italy 3 Department of Mathematics, Computer Science and Economics, University of Basilicata, Via dell’Ateneo Lucano 10, I-85100 Potenza, Italy; [email protected] (G.Q.); [email protected] (R.S.) 4 Department of Economics and Law, University of Macerata, Via Armaroli 43, I-62100 Macerata, Italy; [email protected] 5 Departamento de Economia y Ciencias Sociales, Universitat Politècnica de València, Cami de Vera S/N, ES-46022 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-06500-72261 Received: 15 September 2020; Accepted: 6 October 2020; Published: 9 October 2020 Abstract: Land degradation is more evident where conditions of environmental vulnerability already exist because of arid climate and unsustainable forms of land exploitation. Consequently, semi-arid and dry areas have been identified as vulnerable land, requiring attention from both science and policy perspectives. In some regions, such as the Mediterranean region, land degradation is particularly intense, although there are no extreme ecological conditions. In these contexts, a wide range of formal and informal responses is necessary to face particularly complex and spatially differentiated territorial processes. -

Land Degradation Neutrality

Land Degradation Neutrality: implications and opportunities for conservation Nature Based Solutions to Desertification, Land Degradation and Drought Second Edition 27/08/2015 IUCN Global Drylands Initiative Land Degradation Neutrality: implications and opportunities for conservation Nature Based Solutions to Desertification, Land Degradation and Drought Second Edition 27/08/2015 With contributions from Global Drylands Initiative, CEM, WCEL, WCPA, CEC1 1 Contributors: Jonathan Davies, Masumi Gudka, Peter Laban, Graciela Metternicht, Sasha Alexander, Ian Hannam, Leigh Welling, Liette Vasseur, Jackie Siles, Lorena Aguilar, Lene Poulsen, Mike Jones, Louisa Nakanuku-Diggs, Julianne Zeidler, Frits Hesselink Copyright: ©2015 IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, Global Drylands Initiative, CEM, WCEL, WCPA and CEC. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN and CEM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN,Global Drylands Initiative, CEM, WCEL, WCPA and CEC. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers. Citation: IUCN 2015. Land Degradation Neutrality: implications and opportunities for conservation, Technical Brief Second Edition 27/08/2015. Nairobi: IUCN. 19p. Cover photo: Yurt among green hills, Kazakhstan. -

Land Degradation Due to Mining in India and Its Mitigation Measures

LAND DEGRADATION DUE TO MINING IN INDIA AND ITS MITIGATION MEASURES By Dr. H. B. Sahu and Er. S. Dash Presented by Dr H. B. Sahu Associate Professor Deptt. of Mining Engineering NIT, Rourkela, India Presented at the 2nd International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology, held at Singapore during Feb 26-28, 2011 and Published by IEEE 3/18/2011 1 Land degradation Actual land mass available to man kind: 30% of total global surface area For India • Land area is about 2-3% of the global land area • but supports more than 16% of the global population • The poor per capita land holding stands at 0.32 hectares Calls for due attention to restoration/reclamation of land after mining Mining and its subsequent activities degrade the land to a significant extent. Overburden removal results in a significant loss of rain forest and the rich top soil 3/18/2011 2 3/18/2011 3 3/18/2011 4 Impact of mining on land environment • Water scarcity due to lowering of water table • Soil contamination • Part or total loss of flora and fauna • Air and water pollution • Acid mine drainage More damages go on proceeding in accelerated rates The cumulative effects push the land towards complete degradation. The process works through a cycle known as land degradation cycle The magnitude of impact on environment . varies from mineral to mineral . the potential of the surrounding environment to absorb the negative effects . geographical disposition of mineral deposits . and size of mining operations 3/18/2011 5 Figure 1: Land deterioration cycle 3/18/2011 6 Table 1. -

Water Costs of Afforestation Agric

research highlights FOREST CARBON analysed geoengineering reporting in news waters around Antarctica — influence the Forest disturbance articles, but little experimental investigation response of sea surface temperatures, and Glob. Change Biol. http://doi.org/s6x (2014) about the effect of different frames on public therefore atmospheric temperature, to views has been carried out so far. greenhouse gas and other forcings. Although It is clear that deforestation leads to the Adam Corner and Nick Pidgeon of the two regions are subjected to similar release of carbon stored in tropical forests Cardiff University, UK, have filled this gap greenhouse gas forcing, the Antarctic is also and a great deal of work has been done to with an online experiment, using 412 UK experiencing ozone depletion. estimate how much carbon is emitted as a participants recruited during early 2013. They conclude that at present the cooling result. The carbon implications of forest Participants read a different description of the Antarctic is associated with effects degradation from human disturbances, of geoengineering. In the experimental related to ozone depletion in the region, such as selective logging, understorey condition, the description was ‘framed’ using which is cancelling the warming due to fires and forest fragmentation, remain an analogy to natural processes (for example greenhouse gases. They suggest that this is less well quantified. the release of millions of small particles that a short-term effect, as ozone recovers and Erika Berenguer from Lancaster reflect sunlight into the highest part of the adds to the warming. In contrast, the Arctic University, UK, and co-workers undertook atmosphere was compared with the cooling is experiencing warming that is enhanced the largest field study of its kind so far effect of a volcanic eruption).