Reconstruction of Lost Cultural Heritage Sites and Landscapes: Context of Ancient Objects in Time and Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vlakové Linky S V S Linky PID Vlakové Ř

VLAKOVÉ LINKY S Orientační intervaly linek S (rozsah provozu 4-24 h) HHněviceněvice S4 S32 ŠŠtětítětí S33 MMšenošeno S3 R43 MMladáladá BBoleslavoleslav hhl.l. nn.. Linka Pracovní den Nepracovní den ice 6-9 9-14 14-20 20-24 6-20 20-24 ov HHorníorní PPočaplyočaply R20 R23 KKaninaanina R21 řk KKrnskornsko S1+S7 15(30 ) 30(60) 15( 30 ) 30(60) 30(60) 30(60) e S2+S22 Trvalý stav ke dni 11. 12. 2016 í B DDolníolní BBeřkoviceeřkovice LLiběchoviběchov ŽŽivonínivonín CChotětovhotětov 15-30 30 15-30 30 30 30 rn S3+R 30-6060 30- 60 120 30~6 0 120 U22 U22 o @ HHorní Beřkovice CCítovítov LLužecužec nnadVltavouadVltavou NNebuželyebužely ZZdětíndětín u CChotětovahotětova S4+R S32 R23 15-30(60) 36 0( 0) 30(60) 36 0( 0) 36 0( 0) 36 0( 0) U22 S42 Labe Vlakové linky S v PID LLhotkahotka u MMělníkaělníka KKropáčovaVruticeropáčovaVrutice S5+R 15-30 30 15-3 0 60 3 0 60 c v š s m U22 S42 MMělník-Mlaziceělník-Mlazice be ko tě ve e LLhotkahotka u MMělníkaělníka zzastávkaastávka S6 30(60)6 0 (120) 30(60) 60(120) 60(120) 60(120) o aš ne ně íp KKošátkyošátky za tr MMnetěš ti Ř VVraňanyraňany S7 10-15(30) 30(60) 15(30) 30(60) 30 30(60) ří SStraškov CCtiněvesod HHleďsebeleďsebe BBříza obec p S32 S33 MMělníkělník KKojoviceojovice S8+S88 30(60) 60 30(60) 60 30~60 60 ty S44 MMlčechvostylčechvosty MMělnickáVruticeělnickáVrutice S9 la VVelvaryelvary S3 R43 S33 BByšiceyšice 15(30) 30(60) 15(30) 30-60(60) 30(30-60) 30(60) om NNovéové OOuholiceuholice S11 60 120 60 120 120 120 st VVelkýelký BBorekorek o VVelkáelká BBučinaučina NNelahozeveselahozeves S4 S3 S32 R43 ry S12 30 60 60 60 60 60 KKostomlaty pod Řípem R43 á sy o vč ří S23 60 60(120) 60 60(120) 60(120) 60(120) OOlovnicelovnice zzastávkaastávka NNelahozeveselahozeves zzámekámek S3 VVšetatyšetaty st OOvčáry DDřísy S32 ě S32 S32+R23 30~60 ~60 ~60 ~60 ~60 ~60 S40 S44 m S4 S40 S42 R23 ce e R23 S33 vybrané spoje – vybr. -

Aktualizace Územně Analytických Podkladů 2014

AKTUALIZACE ÚZEMN Ě ANALYTICKÝCH PODKLAD Ů 2014 ROZBOR UDRŽITELNÉHO ROZVOJE ÚZEMÍ ORP ČERNOŠICE TEXTOVÁ ČÁST po řizovatel územn ě analytických podklad ů: MěÚ Černošice, Ú řad územního plánování datum po řízení: prosinec 2014 podpis: otisk ú ředního razítka: Projekt „Zpracování vybraných jev ů z ÚAP pro území ORP Černošice“ byl spolufinancován z prost ředk ů Evropské unie, Evropského fondu pro regionální rozvoj. Zpracovatelský kolektiv: Městský ú řad Černošice, odbor územního plánování Riegrova 1209, 252 28 Černošice tel: 221 982 502, e-mail: [email protected] Ing. Helena Ušiaková Ing. arch. Kristýna Jirsová Ing. Dana Pánková Bc. Alexandra Vlasáková Ing. Kate řina Vrbová Ing. arch. Klára Zv ěrevová Spolupráce (GIS analýzy): Ing. Daniel Franke 2/59 Obsah: I. ÚVOD....................................................................................................................................................4 II. ZJIŠT ĚNÍ A VYHODNOCENÍ UDRŽITELNÉHO ROZVOJE ÚZEMÍ S UVEDENÍM JEHO SILNÝCH A SLABÝCH STRÁNEK, P ŘÍLEŽITOSTÍ A HROZEB (SWOT ANALÝZA).........6 1) HORNINOVÉ PROST ŘEDÍ A GEOLOGIE .................................................................................................................6 2) VODNÍ REŽIM .....................................................................................................................................................6 3) HYGIENA ŽIVOTNÍHO PROST ŘEDÍ .......................................................................................................................7 4) OCHRANA -

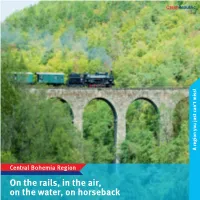

On the Rails, in the Air, on the Water, on Horseback on the Rails, in the Air, on the Water, on Horseback Table of Contents 1

A region you just can’t miss! can’t just you A region On the rails, in the air, on the water, on horseback On the rails, in the air, on the water, on horseback Table of contents 1. On the rails 2 2. In the air 5 3. On the water 9 4. On horseback 13 5. In the countryside 15 Europe Czech Republic Central Bohemia Region www.middleczech.cz Prague On the rails, in the air, on the water, on horseback You can explore the picturesque landscape of Central Bohemia historic train, in a balloon, on a boat or on horseback, you will in various ways. You can ride a bike or go on foot. But how have time to think about what you see around you. And about trying some less traditional ways of travelling? On a without a doubt the Central Bohemia Region has a lot to offer. 1 1. ON THE RAILS In a railway carriage, you will realise how much the times have changed. Board the Sázava Pacific trains When the railway began a hundred and The legendary Central Bohemia railway track leads east from Prague along fifty years ago, people were afraid of it. the river, via Čerčany, to Světlá nad Sázavou. Its name, which is one hun- They thought that it would frighten cattle dred years old, was conceived by the so-called trampers. The railway track and that the speed, until then unheard is characterised by numerous bridges, tunnels and viaducts, of which the of, would suck the air out of the carriages most interesting one is probably the Žampach Viaduct near Jílové u Prahy. -

Strategický Plán Rozvoje Města Mníšek Pod Brdy Na Období 2019–2028

STRATEGICKÝ PLÁN ROZVOJE MĚSTA MNÍŠEK POD BRDY NA OBDOBÍ 2019–2028 ANALYTICKÁ ČÁST Datum vydání: 31.01.2019 OBSAH A. Analytická část ................................................................................. 4 A. 1 Profil města ..................................................................................... 4 1. Území ............................................................................................ 4 2. Obyvatelstvo .................................................................................... 7 3. Hospodářství ................................................................................... 14 3.1 Ekonomická situace ..................................................................................... 14 3.2 Trh práce .................................................................................................. 16 4. Infrastruktura ................................................................................. 19 4.1 Dopravní infrastruktura ................................................................................. 19 4.2 Technická infrastruktura ............................................................................... 23 5. Životní prostředí .............................................................................. 25 6. Vybavenost ..................................................................................... 29 6.1 Bydlení .................................................................................................... 29 6.2 Sociální péče ............................................................................................ -

Tab. 21. District Praha-Západ (AD MEP Černošice) Středočeský Region

Tab. 21. District Praha-západ (AD MEP Černošice) Středočeský Region r Population e b Health Health School m Post office u Type establishment n ha Register office l Code a of municipality i Number Number r e S of municipality of yes=1, no=0, Aged of municipality parts municipality of districts cadastral of Name of municipality of Name either first Cadastral district area, district Cadastral total Aged 65+ 0 - 14 or second stage=* a b c123456 7 891011 Administrative district of municipality with extended powers ČERNOŠICE 1 Bojanovice 539104 3 3 1 090 445 72 79 Mníšek pod Brdy 0 0 0 municipality 2 Bratřínov 571199 1 1 421 179 34 24 Mníšek pod Brdy 0 0 0 municipality 3Březová-Oleško 599735 2 2 648 1 009 186 162 Vrané nad Vltavou 0 0 0 municipality 4 Buš 540048 1 1 685 328 50 46 Štěchovice 0 0 0 municipality 5 Černolice 539121 1 1 319 414 101 55 Dobřichovice 0 0 0 municipality 6 Černošice 539139 1 1 906 6 914 1 450 1 238 Černošice 1 1 1 town 7 Červený Újezd 532215 1 1 534 1 140 241 152 Červený Újezd 0 0 1 municipality 8 Číčovice 539147 1 2 652 284 41 49 Tuchoměřice 0 0 0 municipality 9 Čisovice 539155 2 1 1 200 1 034 182 199 Mníšek pod Brdy 1 * 0 municipality 10 Davle 539163 3 2 747 1 594 320 297 Davle 1 1 1 market town 11 Dobrovíz 539171 1 1 597 537 89 95 Hostivice 0 0 0 municipality 12 Dobříč 539180 1 1 349 314 56 50 Jinočany 0 0 0 municipality 13 Dobřichovice 539198 1 1 1 092 3 488 653 594 Dobřichovice 1 1 1 town 14 Dolní Břežany 539210 4 2 1 064 3 885 982 426 Dolní Břežany 1 1 1 municipality 15 Drahelčice 531146 1 1 477 875 191 102 Rudná -

Základní Skupina Polachových Plánů

IKIS II Poplachové plány (v2) HZS Středočeského kraje Skupina polachových plánů: Základní Adamov - okres Kutná Hora Poplachový plán obce 1. stupeň 2. stupeň 3. stupeň Zvláštní stupeň - stanice Čáslav - Žleby - Ronov nad Doubravou - Červené Janovice - Potěhy - Golčův Jeníkov - Žehušice - Kutná Hora-Malín - Bratčice - Olšany - Třemošnice - Nové Dvory - Šebestěnice - Vrdy - Křesetice - Lipovec - Dolní Bučice - stanice Kolín - stanice Uhlířské Janovice - stanice Kutná Hora Babice - okres Praha-východ Poplachový plán obce 1. stupeň 2. stupeň 3. stupeň Zvláštní stupeň - stanice Říčany - Žernovka - Všestary - Mnichovice (ŘÍ) - Babice - Tehovec - Struhařov (PV) - Úvaly - Doubek - Tehov - Škvorec - Tuklaty - Mukařov (PV) - Říčany - Jevany /219118/ - Rostoklaty - Sibřina - stanice Jílové - stanice Stará Boleslav - stanice Český Brod Bakov nad Jizerou - okres Mladá Boleslav Poplachový plán obce 1. stupeň 2. stupeň 3. stupeň Zvláštní stupeň - stanice Mnichovo Hradiště - ŠKODA AUTO a.s. - Plazy - Loukovec - Bakov nad Jizerou - Mnichovo Hradiště - Kolomuty - Semčice - stanice Mladá Boleslav - stanice Bělá pod Bezdězem - Březno - Dobrovice - Kosmonosy - Klášter Hradiště nad Jizerou - Bělá pod Bezdězem - Katusice - Kněžmost - Chocnějovice - stanice Benátky nad Jizerou - Mladá Boleslav - Podlázky Barchovice - okres Kolín Poplachový plán obce 1. stupeň 2. stupeň 3. stupeň Zvláštní stupeň - stanice Uhlířské Janovice - Horní Kruty - stanice Český Brod - Pečky - Zásmuky - Malotice - Dolní Chvatliny - Mančice - Stříbrná Skalice /219150/ - Kouřim - Drahobudice -

Pražská Integrovaná Doprava Ve Vlacích Ve Doprava Pražská Integrovaná R5

PRAŽSKÁ INTEGROVANÁ DOPRAVA VE VLACÍCH ÚNOR 2016 CO JE PID? OBECNÉ ZÁSADY PID NA ŽELEZNICI průkazkou, ověřenou jejím vydavatelem (právnickou osobou), se jménem, příjmením, datem Integrovaný dopravní systém – Pražská integrovaná doprava (PID) – zahrnuje území hl. m. Do systému PID jsou zařazeny všechny osobní a spěšné vlaky a vyjmenované rychlíky narození a fotografi í, cestují po území hl. m. Prahy (tarifní pásma P, 0 a B) za 0 Kč. Cestující Prahy a přilehlé části Středočeského kraje. Do PID je zařazeno metro, tramvaje, přívozy, (zveřejněné na vývěskách) (dále jen „vlaky PID“) na území hl. m. Prahy (tarifní pásma P, 0 a B) bez prokázání nároku na zvláštní ceny jízdného a ve vnějších pásmech (1–7) platí zvýhodněné lanová dráha na Petřín, městské autobusové linky na území hl. m. Prahy a dále příměstské a v příměstské oblasti (tarifní pásma 1–7). (poloviční) jízdné podle Tarifu PID nebo Tarifu ČD. autobusové linky a železniční tratě, které obsluhují také přilehlé území Středočeského kraje. Použití jízdních dokladů PID je možné ve stanovených vlacích pouze ve 2. vozové třídě. Pro děti od 6 do 15 let (do dne předcházejícímu dni 15. narozenin) a pro seniory od 65 let (ode PID umožňuje na jeden jízdní doklad kombinovat více dopravních prostředků, např. vlak, Děti do 6 let (do dne předcházejícímu dni 6. narozenin) se ve vlacích PID přepravují podle dne 65. narozenin), kteří jsou držiteli karty s nahraným Dokladem o nároku na zvláštní ceny metro a příměstský autobus, různých provozovatelů. Při přestupu není zapotřebí kupovat Tarifu ČD pro vnitrostátní přepravu cestujících a zavazadel (TR10). jízdného (cena dokladu 120 Kč, pro seniory od 70 let 20 Kč) nebo Průkazu dítě 6–15, resp. -

Noční Vlaky PID

Výňatky z jízdních řádů ve směru z Prahy Noční vlaky PID 1 6 Kolín Beroun Noční vlaky v systému PID odjíždějí každý den TP TP Praha hl. n. P 0:30 2:30 Praha hl. n. P 2:34 kolem 0:30 z Prahy (převážně z hlavního nádraží) Praha-Libeň 0 0:36 2:36 Praha-Smíchov 0 0:38 2:41 po hlavních tratích do všech směrů. O víkendových Praha-Klánovice B 0:51 2:52 Praha-Řeporyje B 0:51 2:54 Úvaly 1 0:56 2:57 Rudná u Prahy 1 1:00 3:03 nocích (z pátku na sobotu a ze soboty na neděli) Český Brod 3 1:08 3:09 Nučice 1 1:05 3:08 navíc jedou další vlaky ještě ve 2:30. Poříčany 4 1:14 3:16 Loděnice 2 1:13 3:16 Noční vlaky Pečky 5 1:22 3:24 Beroun 4 1:27 3:30 Ve vlacích platí Tarif PID a dále je možné si pořídit Velim 5 1:29 3:32 jízdné dle tarifu železničního dopravce. Night trains Kolín 6 1:38 3:42 7 Beroun TP Ve vlacích PID neplatí tyto jízdní doklady PID: SMS odjezdyodjezdy z Prahy kolem 00:30:30 2 Poděbrady (Kolín) Praha hl. n. P 0:30 2:30 jízdenky; přestupní dvoupásmové jízdenky PID pro a o víkendechvíkendech takétaké 2:302:30 TP Praha-Smíchov 0 0:37 2:37 jednotlivou jízdu na 15 minut (v ceně 12 Kč, resp. Praha hl. n. P 0:30 2:30 Praha-Radotín B 0:46 2:46 Praha-Vysočany 0 0:36 2:37 Černošice 1 0:50 2:50 3 Kč); zaměstnanecké jízdné PID; zaměstnanecké Čelákovice 2 0:56 2:58 Dobřichovice 1 0:58 2:58 jízdné DP Praha. -

BŘEZEN 2018 PRŮHONICKO ZPRAVODAJ OBCE PRŮHONICE • Zdarma AKTUALITY Z OBECNÍHO ÚŘADU

BŘEZEN 2018 PRŮHONICKO ZPRAVODAJ OBCE PRŮHONICE • zdarma AKTUALITY Z OBECNÍHO ÚŘADU Zvláštní poděkování patří sponzorům, kteří na pokrytí nákladů plesu přispěli částkou 6 000,- Kč a do tomboly OBECNÍ PLES poslali 513 darů. Jmenovitý seznam sponzorů najdete v Obecní ples se konal 10. března v Kongresovém centru dalším textu. DĚKUJEME!!! hotelu Floret, po úvodním předtančení k tanci a poslechu hrál CAROLINE BAND, jako host večera vystoupila s nej- většími hity 50. a 60. let dívčí skupina TOFFEES. Touto cestou děkuji všem kolegům, kteří se na přípravě plesu podíleli. Program tradičně zajistila paní Galina Srpo- vá, předsedkyně kulturní komise obce, za přípravu tombo- ly, organizaci prodeje lístků a vše ostatní děkuji svým ko- legyním z obecního úřadu, paní Ivě Erbenové a Štěpánce Žvejkalové. Za pomoc v den plesu též všem ostatním za- městnancům obecního úřadu, kteří pomáhali s přípravou tomboly a podíleli se na organizační práci během plesu. VELIKONOČNÍ TRH PRŮHONICE Pátek 30.3.2018 900 - 1600 hod. KVĚTNOVÉ NÁMĚSTÍ 1 ZPRAVODAJ OBCE PRŮHONICE BŘEZEN 2018 dohody. Celkem se jedná o 8 díl- čích změn, označených jako Zm2/6 a poté Zm2/11 až Zm2/17. Ostatní OBECNÍ PLES 2018 PODPOŘILI NÁSLEDUJÍCÍ SPONZOŘI: dílčí změny byly obsaženy v již vy- 1) Botanický ústav AV ČR 27) Restaurace V Holi dané změně č. 2 A. 2) Bauhaus 28) Pizza Coloseum Průhonice je nejrozsáhlejší změnou tý- 3) Hornbach Čestlice 29) Volvo truck Center Praha Zm2/6 kající se rozvojového zastavitelného 4) Jiří Křapáček J+A 30) MVDr. Vítězslav Motl území východně od Rozkoše. Zde 5) Paloma Průhonice 31) Zahradnické služby Roušal dochází k účelnější reorganizaci ná- 6) Auto Průhonice a.s. -

Verze K 21. 1. 2019

Místní akční plán vzdělávání na území ORP Černošice č. CZ.02.3.68/0.0/0.0/17_047/0009044 Investiční priority - seznam projektových záměrů pro investiční intervence v SC 2.4 IROP a pro integrované nástroje ITI, IPRÚ a CLLD zpracovaný pro ORP, území MAPII ORP Černošice – AKTUALIZACE 1/2019 Identifikace školy, Název projektu: Očekávané Očekávaný Soulad Typ projektu: školského celkové termín realizace s cílem s vazbou na klíčové kompetence IROP Bezbarié- Rozšiřování zařízení či dalšího náklady na projektu (od – MAP* rovost kapacit subjektu projekt v Kč do) Cizí Přírodní Technické Práce školy, kmenových Název: jazyk vědy ** a s digitál. školského učeben IČO: řemeslné technologie- zařízení mateřských RED IZO: obory ** mi *** **** nebo základních IZO: škol ***** Region Roztocko- Hostivicko NOVĚ zřízená Vybavení učeben ZŠ 3,5 mil do 1.9.2017 1B, 4A, 4B, ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ RH1 Základní škola a pro vzdělávání 5A Mateřská škola v klíčových Noutonice, kompetencích Noutonice 7, (navýšení z 0 na 48 Lichoceves žáků) IČO: 71294317 NOVĚ zřízená Vybavení výdejny 1,4 mil. do 1.9.2017 1B, 1C, 5A ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ RH 1b Základní škola a jídla pro ZŠ Mateřská škola (navýšení z 0 na 48 Noutonice, žáků) Noutonice 7, Lichoceves IČO: 71294317 NOVĚ zřízená Vybavení učeben 1,9 mil do 1.9.2017 1A, 3A, 4A, ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ RH2 Základní škola a MŠ (navýšení z 0 na 4B, 5A Mateřská škola 42 dětí) Noutonice, Noutonice 7, Lichoceves IČO: 71294317 NOVĚ zřízená Vybavení výdejny 1,4 mil. do 1.9.2017 1A, 1C, 5A ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ ☐ RH 2b Základní škola a jídla pro MŠ Mateřská škola Místní akční plán vzdělávání na území ORP Černošice č. -

OPATŘENÍ OBECNÉ POVAHY Zastupitelstva Obce Březová-Oleško

OPATŘENÍ OBECNÉ POVAHY Zastupitelstva obce Březová-Oleško è. 1/2017/OOP ÚZEMNÍ PLÁN BŘEZOVÉ-OLEŠKA OBEC BØEZOVÁ-OLEKO ZASTUPITELSTVO OBCE Hlavní 1143, Oleško, 252 45 Březová-Oleško; okres Praha-západ, kraj Středočeský, IČO 44684983 Tel./fax: 224 283 505; e-mail: [email protected]; http://www.brezova-olesko.cz; IDS: 88qbqnr čj.: OUBO-0983/2017 V Olešku dne: 20. prosince 2017 Vyřizuje: Ing. Vich, PRISVICH, s.r.o. tel. 241444053, mobil 606638956 Opatření obecné povahy č. 1/2017/OOP l ÚZEMNÍ PLÁN BŘEZOVÉ-OLEŠKA *************************************************************** Zastupitelstvo obce Březová-Oleško, příslušné podle § 6 odst. 5 písm. c) zákona č. 183/2006 Sb., o územním plánování a stavebním řádu (stavební zákon), ve znění pozdějších předpisů (dále jen „sta- vební zákon“), za použití § 43 odst. 4 stavebního zákona, § 171 a násl. zákona č. 500/2004 Sb., správní řád, ve znění pozdějších předpisů (dále jen „správní řád“), § 13 a přílohy č. 7 vyhlášky č. 500/2006 Sb., o územně analytických podkladech, územně plánovací dokumentaci a způsobu evidence územně plánovací činnosti, ve znění pozdějších předpisů (dále jen „vyhláška č. 500/2006 Sb.“), svým usnese- ním č. 1/19.12.2017 ze dne 19. prosince 2017 vydává územní plán Březové-Oleška (dále také jen „územní plán“ či „ÚP“), zhotovený společností AURS, spol. s r.o., IČO 25086103, pro- jektantem Ing. arch. Milanem Körnerem, CSc., autorizovaným architektem ČKA 00025, ve formě opa- tření obecné povahy č. 1/2017/OOP (dále také jen „opatření obecné povahy“). Územní plán Březové-Oleška stanovuje -

Vybíráme Z Obsahu Davle a Sport

VYDÁVÁ MĚSTYS DAVLE číslo 353 3/2014 10 Kč Davle a sport Dne 5. července 2014 si na fotbalovém zanikl, a tak k defi nitivnímu založení kde však vydržela pouze jeden rok. hřišti v Davli připomeneme 90. výročí sportovního klubu došlo až 29. led- V Davli se však již v této době hrál i vý- vzniku místní tělovýchovné jednoty. Při na 1928. Nově vzniklý SK Sparta Davle borný lední hokej. této příležitosti se bude na hřišti konat se v roce 1936 probojovala do II. třídy, pokračování na str. 10 sportovní den, večer pak posezení s hud- bou a vyvrcholením oslav bude jako již několikráte předtím fotbalové utkání Slavoj Davle – internacionálová Sparta. Současně je to v letošním roce 105 let od založení Jednoty sokolské, která byla v Davli první sportovní a tělový- chovnou organizací. Prvním sportovním klubem vzniklým již v ČSR byl SK Lvíček Davle založený roku 1921 jako fotbalový klub, který hrál pouze přátelské zápasy. V roce 1924 vznikl SK Davle, který již působil v rám- ci středočeské fotbalové župy, brzy však Vybíráme z obsahu Davle oceněna titulem „Vorařská obec“ str. 2 První mezioddílový závod v judo str. 12 Prapor davelských hasičů ve fi nále str. 13 Aktivity Daveláčku str. 16 Kam za kulturou str. 23 Soutok 3/2014 1 Z městysu nu bylo vyhlášeno výběrové řízení na vy- pracování projektové dokumentace Rozšíření ZŠ Davle na nástavbu ZŠ. Bylo vyzváno 6 projekč- ních kanceláří. Tři projekční kanceláře se pro nedostatek času omluvily. Hod- V letošním roce přišlo k zápisu do ZŠ Da- pouze jedna třída, neboť bude končit notícím kritériem byla výše nabídkové vle rekordních 78 žáčků.