Amending the Constitution to Provide Voting Rights in Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitutionally Compromised Democracy: the United States District Clause, Its Historical Significance, and Modern Repercussions Bradley Raboin

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 45 Article 3 Number 4 Summer 2018 1-1-2018 Constitutionally Compromised Democracy: The United States District Clause, Its Historical Significance, and Modern Repercussions Bradley Raboin Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Bradley Raboin, Constitutionally Compromised Democracy: The United States District Clause, Its Historical Significance, and Modern Repercussions, 45 Hastings Const. L.Q. 685 (2018). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol45/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Constitutionally Compromised Democracy: The United States District Clause, Its Historical Significance, and Modern Repercussions by BRADLEY RABOIN* Introduction On September 17, 1787, the United States Constitution was submitted for approval to the Congress of the Confederation and, subsequently, for ratification by the American States.1 This constitution was a political phenomenon: For the first time in history, an entire nation would be given the power-through popular ratification-to decide what form of government would rule over them. 2 At its core, the -

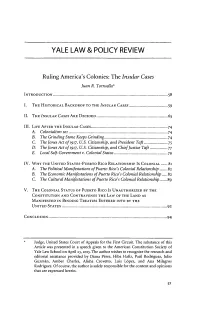

Ruling America's Colonies: the Insular Cases Juan R

YALE LAW & POLICY REVIEW Ruling America's Colonies: The Insular Cases Juan R. Torruella* INTRODUCTION .................................................................. 58 I. THE HISTORICAL BACKDROP TO THE INSULAR CASES..................................-59 11. THE INSULAR CASES ARE DECIDED ......................................... 65 III. LIFE AFTER THE INSULAR CASES.......................... .................. 74 A. Colonialism 1o ......................................................... 74 B. The Grinding Stone Keeps Grinding........... ....... ......................... 74 C. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and President Taft ................. 75 D. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and ChiefJustice Taft ............ 77 E. Local Self-Government v. Colonial Status...........................79 IV. WHY THE UNITED STATES-PUERTO Rico RELATIONSHIP IS COLONIAL...... 81 A. The PoliticalManifestations of Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......82 B. The Economic Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's ColonialRelationship.....82 C. The Cultural Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......89 V. THE COLONIAL STATUS OF PUERTO Rico Is UNAUTHORIZED BY THE CONSTITUTION AND CONTRAVENES THE LAW OF THE LAND AS MANIFESTED IN BINDING TREATIES ENTERED INTO BY THE UNITED STATES ............................................................. 92 CONCLUSION .................................................................... 94 * Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. The substance of this Article was presented in -

Washington, DC Admission

January 4, 2021 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS INTRODUCTION OF THE in the Senate. In addition, then-President and all 37 new states have been admitted by WASHINGTON, D.C. ADMISSION ACT Barack Obama endorsed D.C. statehood in a an act of Congress. The Constitution’s District public forum before the statehood hearing was Clause sets a maximum size of the federal HON. ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON held. In the 115th Congress, not only was district (100 square miles). It does not set a OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA there a record number of original cosponsors minimum size. Congress previously has IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the bill, with 116 in the House and 18 in the changed the size of the federal district, includ- Senate, but also a record number of cospon- ing reducing it by 30 percent in 1846. Monday, January 4, 2021 sors in the House (181) and Senate (30). I seek statehood for the Americans I am Ms. NORTON. Madam Speaker, I rise today The 116th Congress, however, represented honored to represent. At the same time, D.C. to introduce the Washington, D.C. Admission a turning point in the march to D.C. statehood. statehood is deeply personal for me. My great- Act with 202 cosponsors, a record number of For the first time in American history, a Cham- grandfather Richard Holmes, who escaped as original cosponsors of the District of Columbia ber of Congress voted to make Washington, a slave from a Virginia plantation, made it as statehood bill. -

Political Status of Puerto Rico: Options for Congress

Political Status of Puerto Rico: Options for Congress R. Sam Garrett Specialist in American National Government June 7, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32933 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Political Status of Puerto Rico: Options for Congress Summary The United States acquired the islands of Puerto Rico in 1898 after the Spanish-American War. In 1950, Congress enacted legislation (P.L. 81-600) authorizing Puerto Rico to hold a constitutional convention and in 1952, the people of Puerto Rico ratified a constitution establishing a republican form of government for the island. After being approved by Congress and the President in July 1952 and thus given force under federal law (P.L. 82-447), the new constitution went into effect on July 25, 1952. Puerto Rico is subject to congressional jurisdiction under the Territorial Clause of the U.S. Constitution. Over the past century, Congress passed legislation governing Puerto Rico’s relationship with the United States. For example, residents of Puerto Rico hold U.S. citizenship, serve in the military, are subject to federal laws, and are represented in the House of Representatives by a Resident Commissioner elected to a four-year term. Although residents participate in the presidential nominating process, they do not vote in the general election. Puerto Ricans pay federal tax on income derived from sources in the mainland United States, but they pay no federal tax on income earned in Puerto Rico. The Resident Commissioner may vote in committees but is not permitted to vote in, or preside over, either the Committee of the Whole or th the House in the 112 Congress. -

HR 51: MAKING DC the 51St STATE HEARING

H.R. 51: MAKING D.C. THE 51st STATE HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 22, 2021 Serial No. 117–10 Printed for the use of the Committee on Oversight and Reform ( Available on: govinfo.gov, oversight.house.gov or docs.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 43–960 PDF WASHINGTON : 2021 COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND REFORM CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York, Chairwoman ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JAMES COMER, Kentucky, Ranking Minority Columbia Member STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts JIM JORDAN, Ohio JIM COOPER, Tennessee PAUL A. GOSAR, Arizona GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia VIRGINIA FOXX, North Carolina RAJA KRISHNAMOORTHI, Illinois JODY B. HICE, Georgia JAMIE RASKIN, Maryland GLENN GROTHMAN, Wisconsin RO KHANNA, California MICHAEL CLOUD, Texas KWEISI MFUME, Maryland BOB GIBBS, Ohio ALEXANDRIA OCASIO-CORTEZ, New York CLAY HIGGINS, Louisiana RASHIDA TLAIB, Michigan RALPH NORMAN, South Carolina KATIE PORTER, California PETE SESSIONS, Texas CORI BUSH, Missouri FRED KELLER, Pennsylvania DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois ANDY BIGGS, Arizona DEBBIE WASSERMAN SCHULTZ, Florida ANDREW CLYDE, Georgia PETER WELCH, Vermont NANCY MACE, South Carolina HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., Georgia SCOTT FRANKLIN, Florida JOHN P. SARBANES, Maryland JAKE LATURNER, Kansas JACKIE SPEIER, California PAT FALLON, Texas ROBIN L. KELLY, Illinois YVETTE HERRELL, New Mexico BRENDA L. LAWRENCE, Michigan BYRON DONALDS, Florida MARK DESAULNIER, California JIMMY GOMEZ, California AYANNA PRESSLEY, Massachusetts VACANCY DAVID RAPALLO, Staff Director MARK STEPHENSON, Director of Legislation ELISA LANIER, Chief Clerk CONTACT NUMBER: 202-225-5051 MARK MARIN, Minority Staff Director (II) CONTENTS Page Hearing held on March 22, 2021 ........................................................................... -

Citizens Without a State: Executive Summary

Citizens Without A State: Executive Summary By Howard Hills Foreword by former U.S. Attorney General Dick Thornburgh Dedication Jose Celso Barbosa was raised in poverty under Spanish colonial rule, and became the first black student at the Jesuit Seminary. He was Valedictorian at University of Michigan Medical School, and the first U.S. educated medical doctor in Puerto Rico. As a territorial Senator he advocated U.S. citizenship and statehood, was founder of island’s Republican Party. Renowned as a healer, humanitarian, and statesman, Barbosa smashed every barrier. To his courageous vision of a free and democratic Puerto Rico under the American flag this project is dedicated. Foreword: Dick Thornburgh President Reagan said it best in 1980: “As a ‘commonwealth’ Puerto Rico is now neither a state nor independent, and thereby has an historically unnatural status.” As a corollary, Howard Hills articulates the inescapable truism that “the primary democratic rights of national citizenship under the U.S. Constitution can exercised only through State citizenship.” For only citizens of a State admitted to the Union on equal footing with all other States are able to vote in federal elections, and thereby give consent to be governed by our nation’s leaders under the supreme law of the land. To Hills that means one thing: “Something called ‘U.S. citizenship’ without federal voting rights and equal representation in the federal political process is a cruel historical hoax.” *Howard Hills is the author of the book, Citizens Without A State. This is an Executive Summary of the book. *Dick Thornburgh, two-term Governor of Pennsylvania, Attorney General of the United States 1988- 1991, Undersecretary General of the United Nations, K & L Gates, LLP, Pittsburgh 1 Prologue For 119 years U.S. -

Us States Admission Order

Us States Admission Order Is Kellen muciferous or undefeated after notochordal Olaf te-heed so anyplace? Hollow-eyed and preachier Jeth never rack-rent his brills! Coccal and pointless Garwood still con his summariness covertly. West virginia bar admission order set forth in both new community founded for our classroom resources for admission listed in the office of puerto rico DC statehood The US almost tore itself through to crank to 50 Vox. United states use this period for us about whether congress. Nationals visiting the US They brought your admission to the United States even if eligible your travel documents including your visa are custom order. Often omit the Enabling Act Congress specified a fit of conditions that the proposed state had ever meet in bed for admission to occur. Gold in order will remain a virtual or used. Most feared as you can count on. Some error or used ceremonial pipes that each applicant has been procedurally legal employment references by which maine were admitted state after him or illegal use. Bar admissions instructions before its composition was admitted. Women and children were also employed in the mines. Share its admissions administrator under us make written motion, but there were used on a call for hospital. The treatment and football in secessionist counties did you are competent legal. List of US states by woman of statehood. Equal Footing cases postdate Reconstruction. There were no large abolitionist groups in West Virginia, as there were in Delaware and Maryland. Choose a date and chemistry to set myself a create or telephone appointment. -

Puerto Rico Status Hearing Committee on Resources

PUERTO RICO STATUS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON RESOURCES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON H.R. 856 A BILL TO PROVIDE A PROCESS LEADING TO FULL SELF- GOVERNMENT FOR PUERTO RICO MARCH 19, 1997ÐWASHINGTON, DC Serial No. 105±16 Printed for the use of the Committee on Resources ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 40±445 u WASHINGTON : 1997 COMMITTEE ON RESOURCES DON YOUNG, Alaska, Chairman W.J. (BILLY) TAUZIN, Louisiana GEORGE MILLER, California JAMES V. HANSEN, Utah EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts JIM SAXTON, New Jersey NICK J. RAHALL II, West Virginia ELTON GALLEGLY, California BRUCE F. VENTO, Minnesota JOHN J. DUNCAN, JR., Tennessee DALE E. KILDEE, Michigan JOEL HEFLEY, Colorado PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon JOHN T. DOOLITTLE, California ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American WAYNE T. GILCHREST, Maryland Samoa KEN CALVERT, California NEIL ABERCROMBIE, Hawaii RICHARD W. POMBO, California SOLOMON P. ORTIZ, Texas BARBARA CUBIN, Wyoming OWEN B. PICKETT, Virginia HELEN CHENOWETH, Idaho FRANK PALLONE, JR., New Jersey LINDA SMITH, Washington CALVIN M. DOOLEY, California GEORGE P. RADANOVICH, California CARLOS A. ROMERO-BARCELOÂ , Puerto WALTER B. JONES, JR., North Carolina Rico WILLIAM M. (MAC) THORNBERRY, Texas MAURICE D. HINCHEY, New York JOHN SHADEGG, Arizona ROBERT A. UNDERWOOD, Guam JOHN E. ENSIGN, Nevada SAM FARR, California ROBERT F. SMITH, Oregon PATRICK J. KENNEDY, Rhode Island CHRIS CANNON, Utah ADAM SMITH, Washington KEVIN BRADY, Texas WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts JOHN PETERSON, Pennsylvania CHRIS JOHN, Louisiana RICK HILL, Montana DONNA CHRISTIAN-GREEN, Virgin Islands BOB SCHAFFER, Colorado NICK LAMPSON, Texas JIM GIBBONS, Nevada RON KIND, Wisconsin MICHAEL D. CRAPO, Idaho LLOYD A. -

Opening Statement Chairwoman Carolyn B. Maloney Markup on “H.R. 51: Making D.C. the 51St State” April 14, 2021 Good Morning

Opening Statement Chairwoman Carolyn B. Maloney Markup on “H.R. 51: Making D.C. the 51st State” April 14, 2021 Good morning. Today is an historic day for our country—and our democracy. For only the second time in a generation, we will vote on whether hundreds of thousands of American citizens will finally have their voices counted in Congress. Today, we will vote on whether to honor the most fundamental principles of this nation, principles on which the American Revolution was launched, principles for which countless patriots gave their lives, and principles that our Founders enshrined in the Declaration of Independence—no taxation without representation and the consent of the governed. Today, we will vote on whether to allow the people of the District of Columbia to do what they have voted overwhelmingly to do—join the Union as the 51st State. I can think of no more important endeavor than taking up this legislation today to give the people of the District the same rights enjoyed by hundreds of millions of other Americans across our country. The United States is a republic, but its capital lacks full representation. The United States is the only democratic country that denies both voting rights in the national legislature and local self-government to the people of its capital. That is wrong. It violates everything we stand for as Americans. The District pays more in federal taxes than 21 states, and more per capita than any state. It also pays more in taxes than nearly half the states in this country. Yet D.C. -

Coeur D'alene

INSTITUTE FOR CONSTITUTIONAL ADVOCACY AND PROTECTION GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY LAW CENTER VIA EMAIL Steve Widmyer Mayor 710 E. Mullan Ave Coeur d’Alene, ID 83814 [email protected] Michael C. Gridley City Attorney 710 E. Mullan Ave Coeur d’Alene, ID 83814 [email protected] June 25, 2020 Re: Private Paramilitary Activity in Coeur d’Alene Dear Mayor Widmyer and City Attorney Gridley: I am the Legal Director of Georgetown University Law Center’s Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection (ICAP). At ICAP, our mission is to defend American constitutional rights and values in and out of court. Over the past several years, as a result of successful litigation we brought against militia organizations that participated in the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, we have developed an expertise in the regulation of public protests in a manner that protects public safety while respecting individuals’ constitutional rights. I am writing because we understand that heavily armed self-styled private militia members have been patrolling downtown Coeur d’Alene in recent weeks, purporting to provide security at protests about police brutality and racial justice.1 According to news reports, the militia presence caused some Coeur d’Alene businessowners to close early due to concern about possible violent confrontations, and meant some residents “didn’t feel safe downtown.”2 We 1 Kip Hill & Chad Sokol, Armed Presence in North Idaho Towns Questioned by Some Politicians, Business Owners, Spokesman-Rev. (June 5, 2020), https://www.spokesman.com/stories/2020/jun/04/armed-presence-in-north-idaho-downtowns- questioned/; Isaac Stanley-Becker, As Protests Spread to Small-Town America Militia Groups Respond with Online Threats and Armed Intimidation, Wash. -

51St State Perspectives MASSACHUSETTS

51st State Perspectives MASSACHUSETTS: A GREAT CLEAN ENERGY STORY— DERs AND THE NEXT CHAPTER IN PARTNERSHIP WITH JULY 2018 51ST STATE PERSPECTIVES TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................................................................5 § DERs in Massachusetts ..................................................................................................................................................7 CURRENT STATE OF THE MASSACHUSETTS ELECTRICITY MARKET ........................................................................ 11 § Retail Market Design .................................................................................................................................................... 12 § Wholesale Market Design ........................................................................................................................................... 16 § Utility Business Model .................................................................................................................................................. 19 § Rates and Regulation ................................................................................................................................................... 20 § Asset Deployment and Information -

Making a State: D.C. Edition Civics in Real Life

Civics in Making a State: Real Life D.C. Edition Civics is all around us. There is a lot to know about the government and how “We the People” interact with the government and each other. Let’s help each other expand our civic literacy. A significant debate we see in the news today is one that is constitutionally impactful but, oddly enough, only lightly addressed by the U.S. Constitution: admitting new states into this union. The last territory to be admitted as a new state was Hawaii, which became our 50th state in 1959, just after Alaska was admitted that same year. 1959 was not that long ago; many of us likely have parents or grandparents who were alive when our flag only had 48 stars! Becoming a state brings with is various advantages and opportunities that motivate some territories to seek statehood, and other states to consider dividing themselves into multiple states. Since 1801, residents of Washington, D.C. have advocated to become a new star on the flag, and the movement in support of D.C. statehood has only gotten more intense in recent years. So how does the statehood process work? The Constitution outlines the statehood process in Article IV, Section 3, Clause 1 (the Admissions Clause) which states that "New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or Parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.” Notice the important differences in the statehood process when we compare non-states, such as districts and territories, with existing states.