Lemmel7-8-Verdict-Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2003-2004 Amernet String Quartet: Strings of the Heart Series

I CONSERVATORY OF Music presents Al\1ERNET STRING QUARTET Strings of the Heart Series with Sergiu Schwartz ~ violin Sylvia Kim~ violin Dmitry Pogorelov ~viola Johanne Perron ~ cello and Tao Lin ~ harpsichord Friday, October 17, 2003 7:30p.m. Amamick-Goldstein Concert Hall de Hoemle International Center Program String Quartet No. 19 in C Major, K 465 "Dissonance" ..... W. A. Mozart (1756-1791) Adagio-Allegro Andante Cantabile Menuetto-Allegro Allegro Amernet String Quartet Misha Vitenson - violin Marsha Littley- violin Michael Klotz- viola Javier Arias- cello Concerto ind minor for Two Violins, BWV 1043 .............. J. S. Bach (1685-1750) Vivace Largo ma non tanto Allegro Sergiu Schwartz-violin Misha Vitenson - violin Marcia Littley, Sylvia Kim-violin Michael Klotz, Dmitry Pogorelov -viola Javier Arias, Johanne Perron-cello Tao Lin - harpsichord INTERMISSION 1 Octet, Op. 20 .................................................................... Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Allegro moderato Andante Scherzo -Allegro leggierissimo Presto Misha Vitenson, Sergiu Schwartz, Sylvia Kim, MarciaLittley-violin Michael Klotz, Dmitry Pogorelov -viola Javier Arias, Johanne Perron-cello Biographies r Amernet String Quartet The Amernet String Quartet, Ensemble-in-Residence at Northern .,_ Kentucky University, has garnered worldwide praise and recognition as one of today's exceptional young string quartets. i It rose to international attention after only one year of existence, after winning the Gold Medal at the 7th Tokyo International Music Competition in 1992. Three years later the group was the First Prize winner of the prestigious 5th Banff International String Quartet Competition. The Amernet String Quartet has been described by The New York Times as "an accomplished and intelligent ensemble," and by the Niirnberger Nachrichten (Germany) as "fascinating with flawless intonation, extraordinary beauty of sound, virtuosic brilliance and homogeneity of ensemble." The Amernet String Quartet formed in 1991, while two of its members were students at The Juilliard School. -

FRANZ SCHUBERT VLADIMIR FELTSMAN Franz Schubert a Tribute to Scriabin NI6198 Sonata No

FRANZ SCHUBERT VLADIMIR FELTSMAN Franz Schubert A Tribute to Scriabin NI6198 Sonata No. 4 Op. 30, Valse Op. 38, Danses Op. 73, Vers la flamme Op. 72, Piano Sonatas Volume 6 Valse Op. Posth., Selections from Preludes Op. 11, 16, 22, 37, 74, Poémes Op. 32, 63 Morceaux Op. 49, 51, 57, Etudes Op.42 Vladimir Feltsman A Tribute to Silvestrov NI6317 Music by Valentin Sivestrov, CPE Bach, Schubert, Scarlatti, DISC ONE Chopin, Schumann and Wagner. 1 12 Valses nobles D 969 (pub.1827) 8.35 A Tribute to Prokofiev NI6361 Sonata in A-flat major D 557 (1817) 11.44 Story Op. 3, Remembrance Op. 4, Prelude in C Harp Op. 12, Visions fugitives Op. 22, Sarcasms Op. 17, Music for Children Op. 65, Two pieces from Cinderella, 2 I Allegro moderato 3.50 3 II Andante 3.26 Forgotten Russians NI6377 4 III Allegro 4.28 Music by Stanchinsky, Feinberg, Obukhov, Lourié, Roslavets, Mosolov, and Protopopov For track lists visit www.wyastone.co.uk 5 Scherzo in D D 570 (1817) Allegro vivace 3.12 Klavierstücke D 459 (1816) 22.34 VLADIMIR FELTSMAN Pianist and conductor Vladimir Feltsman is one of the 6 [I] Allegro moderato D 459/1 8.03 most versatile and constantly interesting musicians of our time. His vast repertoire 7 [II] Adagio D 459/3 6.14 encompasses music from the Baroque to 20th-century composers. A regular guest soloist 8 [III] Scherzo con trio. Allegro D 459/4 3.15 with leading symphony orchestras in the United States and abroad, he appears in the most 9 [IV] Scherzo. -

2016 Program Booklet

Rebecca Penneys Piano Festival Fourth Year July 12 – 30, 2016 University of South Florida, School of Music 4202 East Fowler Avenue, Tampa, FL The family of Steinway pianos at USF was made possible by the kind assistance of the Music Gallery in Clearwater, Florida Rebecca Penneys Ray Gottlieb, O.D., Ph.D President & Artistic Director Vice President Rebecca Penneys Friends of Piano wishes to give special thanks to: The University of South Florida for such warm hospitality, USF administration and staff for wonderful support and assistance, Glenn Suyker, Notable Works Inc., for piano tuning and maintenance, Christy Sallee and Emily Macias, for photos and video of each special moment, and All the devoted piano lovers, volunteers, and donors who make RPPF possible. The Rebecca Penneys Piano Festival is tuition-free for all students. It is supported entirely by charitable tax-deductible gifts made to Rebecca Penneys Friends of Piano Incorporated, a non-profit 501(c)(3). Your gifts build our future. Donate on-line: http://rebeccapenneyspianofestival.org/ Mail a check: Rebecca Penneys Friends of Piano P.O. Box 66054 St Pete Beach, Florida 33736 Become an RPPF volunteer, partner, or sponsor Email: [email protected] 2 FACULTY PHOTOS Seán Duggan Tannis Gibson Christopher Eunmi Ko Harding Yong Hi Moon Roberta Rust Thomas Omri Shimron Schumacher D mitri Shteinberg Richard Shuster Mayron Tsong Blanca Uribe Benjamin Warsaw Tabitha Columbare Yueun Kim Kevin Wu Head Coordinator Assistant Assistant 3 STUDENT PHOTOS (CONTINUED ON P. 51) Rolando Mijung Hannah Matthew Alejandro An Bossner Calderon Haewon David Natalie David Cho Cordóba-Hernández Doughty Furney David Oksana Noah Hsiu-Jung Gatchel Germain Hardaway Hou Jingning Minhee Jinsung Jason Renny Huang Kang Kim Kim Ko 4 CALENDAR OF EVENTS University of South Florida – School of Music Concerts and Masterclasses are FREE and open to the public Donations accepted at the door Festival Soirée Concerts – Barness Recital Hall, see p. -

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra LORIN MAAZEL, Music Director-Designate

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra LORIN MAAZEL, Music Director-Designate MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Conductor VLADIMIR FELTSMAN, Pianist WEDNESDAY EVENING, APRIL 27, 1988, AT 8:00 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Symphony No. 6 in F major, Op. 68 ("Pastoral") ............... BEETHOVEN Allegro ma non troppo (Awakening of Joyful Feelings Upon Arriving in the Country) Andante molto mosso (Scene by the Brook) Allegro (Merry Gathering of Country Folk) Allegro (Tempest, Storm) Allegretto (Shepherds' Hymn: Glad and Thankful Feelings After the Storm) INTERMISSION Concerto No. 3 in D minor for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 30 . RACHMANINOFF Allegro ma non tanto Intermezzo: adagio Finale: alia breve VLADIMIR FELTSMAN Bravo to May Festival Underwriters In the spirit of honoring the past and ensuring the future, these families and individuals have demonstrated their support by underwriting the artist fees and major production costs of this 95th Annual May Festival. Representing both long-time Ann Arbor arts patrons and a new generation of leadership in the cultural life of this community, these donors are committed to maintaining the Musical Society's tradition of excellence through their public-spirited generosity. We gratefully recognize the following: Dennis A. Dahlmann Mrs. Theophile Raphael Mr. and Mrs. Peter N. Heydon Eileen and Ron Weiser with Elizabeth E. Kennedy McKinley Associates, Inc. Bill and Sally Martin An anonymous family The Power Foundation Forty-second Concert of the 109th Season Ninety-fifth Annual May Festival PROGRAM NOTES by Dr. FREDERICK DORIAN in collaboration with Dr. JUDITH MEIBACH Symphony No. 6 in F major, Op. 68 ("Pastoral") . -

Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) Born at Oneg, Novgorod Region. He had piano lessons from an early age but his serious training in composition began at the Moscow Conservatory where he studied counterpoint with Sergei Taneyev and harmony with Anton Arensky. He began to compose and for the rest of his life divided his musical time between composing, conducting and piano playing gaining great fame in all three. After leaving Russia permanently in 1917, the need to make a living made his role as a piano virtuoso predominant. His 4 Piano Concertos, Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini and substantial solo piano works make him one of the world's most-performed composers. However, he also composed operas and liturgical choral works as well as other pieces for orchestra, chamber groups and voice. Piano Concerto No. 1 in F-sharp minor, Op. 1 (1892, rev. 1917) Leif Ove Andsnes (piano)/Antonio Pappano/Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Piano Concerto No. 2) EMI CLASSICS 74813-2 (2005) Agustin Anievas (piano)/Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos/New Philharmonia Orchestra ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2, 3 and 4, Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Prelude in C-sharp minor, 10 Preludes and 12 Preludes) EMI CLASSICS TRIPLE 5 00871-2 (2007) (original LP release: ANGEL SCB 3801 {3 LPs}) (1973) Vladimir Ashkenazy (piano)/Bernard Haitink/Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (+ Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini) DECCA 417613-2 (1987) Vladimir Ashkenazy (piano)/André Previn/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2, 3 and 4, Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Variations on a Theme of Corelli and Piano Sonata No. -

Russian Music for Cello & Piano

Russian Music for Cello & Piano wendy warner cello irina nuzova piano In fond memory of my mentor, Mstislav Rostropovich. — WENDY WARNER Russian Music for Cello & Piano wendy warner cello irina nuzova piano Producer James Ginsburg Engineer Bill Maylone Recorded October 27–30, 2008, in the Fay and Daniel Levin Performance Studio, WFMT, Chicago Cello Pietro Guarneri II, Venice c.1739, nikolai miaskovsky (1881–1950) “Beatrice Harrison” Cello bow François Xavier Tourte, c.1815, the “De Lamare” on extended loan Sonata No. 2 in A minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 81 (23:11) through the Stradivari Society of Chicago Steinway Piano Charles Terr, Technician Design Kstudio, I. Allegro moderato (9:42) II. Andante cantabile (7:26) III. Allegro con spirito (5:56) Christiaan Kuypers Photography Lisa-Marie Mazzucco alexander scriabin (1872–1915) Etude Op. 8 No. 11 for Piano Solo (4:03) Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit Transcription for cello and piano by Gregor Piatigorsky foundation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation’s activities are supported in part by contributions and grants alfred schnittke (1934–1998) from individuals, foundations, corporations, and government agencies including the Alphawood Musica Nostalgica, for Violoncello and Piano (3:22) Foundation, Irving Harris Foundation, Kirkland & Ellis Foundation, The MacArthur Fund for Arts and Culture at Prince, NIB Foundation, Negaunee Foundation, Sage Foundation, Chicago Department sergei prokofiev (1891–1953) of Cultural Affairs (CityArts III Grant), and the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. Contributions to Adagio from Ten Pieces from the Ballet Cinderella, Op 97b (3:51) The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation may be made at www.cedillerecords.org or 773-989-2515. -

Rudolf Serkin Papers Ms

Rudolf Serkin papers Ms. Coll. 813 Finding aid prepared by Ben Rosen and Juliette Appold. Last updated on April 03, 2017. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2015 June 26 Rudolf Serkin papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 6 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 I. Correspondence.................................................................................................................................... 9 II. Performances...................................................................................................................................274 -

2017 Jury Biographies

Robert Hamilton, USA Internationally respected pianist and recording artist Robert Hamilton has been jury enthusiastically reviewed by two chief music critics for The New York Times. Harold C. Schonberg (who also authored The Great Pianists) wrote: “He is a very Baruch Meir, Israel/USA fine artist. All of Hamilton’s playing has color and sensitivity...one of the best of Chairman of the Jury the million or so around.” And Donal J. Henahan reported: “It was an enthralling listening experience. We must hear this major piano talent again, and soon!” “…Baruch Meir is an exceptional artist. He did a beautiful performance of my piano work entitled A Little Suite for Christmas, which was distinguished Robert Hamilton studied at Indiana University with the first winner of the by deep musical insights and consummate technical skill. It was certainly one coveted Levintritt award, Sidney Foster, graduating summa cum laude. A move of the very finest performances this work of mine has ever received.” to New York City brought studies with Dora Zaslavsky of the Manhattan School, coaching from legendary pianist Vladimir Horowitz, and a host of monetary awards from the Rockefeller – George Crumb, composer; 1968 Pulitzer Prize in Music; Fund and U.S. State Department, launching a strong career and the winning of five major international 2001 Grammy award; 2004 Musical America Composer of the Year. competitions. Pianist Baruch Meir is one of only 65 artists worldwide named Bösendorfer Concert Artist since the founding Hamilton has made countless tours of four continents, appearing in most music capitals. His orchestral of the company in 1828. -

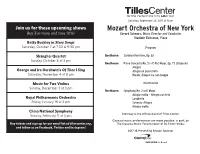

Mozart Orchestra of New York

Saturday, September 23, 2017 at 8 pm Join us for these upcoming shows Mozart Orchestra of New York Buy 3 or more and save 10%! Gerard Schwarz, Music Director and Conductor Vladimir Feltsman, Piano Betty Buckley in Story Songs Saturday, October 7 at 7:30 & 9:30 pm Program Shanghai Quartet Beethoven Coriolan Overture, Op. 62 Sunday, October 8 at 3 pm Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat Major, Op. 73 (Emperor) Allegro George and Ira Gershwin’s Of Thee I Sing Adagio un poco moto Saturday, November 4 at 8 pm Rondo: Allegro ma non troppo Music for Two Violins Intermission Sunday, December 3 at 3 pm Beethoven Symphony No. 2 in D Major Adagio molto – Allegro con brio Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Larghetto Friday, January 19 at 8 pm Scherzo: Allegro Allegro molto China National Symphony Steinway is the official piano of Tilles Center. Sunday, February 11 at 3 pm Classical music performances are made possible, in part, by Buy tickets and sign up for our email list at tillescenter.org, The Classical Music Fund in honor of Dr. Elliott Sroka. and follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram! 2017-18 Presenting Season Sponsor NOTES ON THE PROGRAM 1807, the drama was no longer frequently While he was composing this work, score as an integral part, giving the music The following program notes are performed; nevertheless, Beethoven’s Beethoven, whose hearing was already continuity, but at the same time denying copyright Susan Halpern, 2017. composition quickly became a popular poor, felt tortured by the noise of the the soloist opportunity for impromptu concert piece. -

The Royal Conservatory of Music Glenn Gould School Bachelor of Music; Performance (Honours) Degree Submission

The Royal Conservatory of Music Glenn Gould School Bachelor of Music; Performance (Honours) Degree Submission Prepared For: The Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities, Ontario August 27, 2015 Program Review 1 | P a g e 1 Introduction Submission Title Page: Organization and Program Information Full Legal Name of Organization: The Royal Conservatory of Music Operating Name of Organization: The Royal Conservatory URL for Organization Homepage: www.rcmusic.ca/ggs Proposed Degree Nomenclature: Glenn Gould School Bachelor of Music; Performance (Honours) Location where program to be delivered: 273 Bloor Street West, Toronto, ON M5S 1W2 Contact Information for Information Angela Elster about this submission: Senior Vice President, Research and Education The Royal Conservatory 273 Bloor Street West Toronto, ON M5S 1W2 Tel: (416) 408-2824 ext. 297 Fax: (416) 408-3096 Email: [email protected] Site Visit Coordinator: Jeremy Trupp Manager, Operations The Glenn Gould School The Royal Conservatory TELUS Centre for Performance and Learning 273 Bloor Street West Toronto, ON M5S 1W2 Tel: (416) 408-2824 ext. 334 Fax: (416) 408-5025 Email: [email protected] Anticipated Start Date: September 2016 Anticipated Enrolment for the first 4 125 – 130 students, 55 of whom will be years of the program: participating in the Bachelor of Music, Performance (Honours) 2 | P a g e Table of Contents Program Review 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 2 Submission Title -

Madison Symphony Orchestra Program Notes October 15-16-17, 2021 96Th Season Michael Allsen

Madison Symphony Orchestra Program Notes October 15-16-17, 2021 96th Season Michael Allsen This program opens with a brilliant orchestral showpiece, Ravel’s Spanish- inflicted Alborada del gracioso. We are proud to welcome back pianist Olga Kern for her fourth appearance with the Madison Symphony Orchestra. She previously performed in 2008 (Beethoven’s third concerto), 2010 (Rachmaninoff’s second concerto), and 2014 (Rachmaninoff’s first concerto). Here, she plays Rachmaninoff’s last major composition for piano and orchestra, and a work of stunning virtuosity, the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. Our season-long tribute to Beethoven continues with his monumental Eroica Symphony. Ravel’s Alborada del gracioso (“Morning Song of a Jester”) is his orchestrated version of a 1905 piano work. Ravel was fiercely proud of his mother’s Basque heritage, and this is one of many of his compositions in a Basque or Spanish style. Maurice Ravel Born: March 17, 1875, Cibourne, Basses-Pyrénées, France. Died: December 28, 1937, Paris, France. Alborada del gracioso • Composed: Written in 1904-1905 as a piano work; orchestrated in 1918. • Premiere: May 17, 1919 in Paris, with Rhené-Baton conducting the Pasdeloup Orchestra. • Previous MSO Performance: 1968. • Duration: 8:00. Background Ravel was born to a Swiss father and a Basque mother in Cibourne—a small seaside town in the Basque region near France’s border with Spain. Though his family moved to Paris when he was just three months old, he remained emotionally connected to his mother’s heritage throughout his life, and many of his works channel influences from Basque and Spanish music. -

Prokofiev (1891-1953)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) Born in Sontsovka, Yekaterinoslav Oblast, Ukraine. He was a prodigy who played the piano and composed as a child. His formal training began when Sergei Taneyev recommended as his teacher the young composer and pianist Reinhold Glière who spent two summers teaching Prokofiev theory, composition, instrumentation and piano. Then at the St. Petersburg Conservatory he studied theory with Anatol Liadov, orchestration with Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and conducting with Nikolai Tcherepnin. He went on to become one of Russia's greatest composers, excelling in practically every genre of music. He left the Soviet Union in 1922, touring as a pianist and composing in Western Europe and America, but returned home permanently in 1936. Piano Concerto No. 1 in D flat major, Op. 10 (1911-2) Dmitri Alexeev (piano)/Mariss Jansons/Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Rachmaninov: Piano Concerto No. 3) LENINGRAD MASTERS LM 1312 (1997) Martha Argerich (piano)/Charles Dutoit/Montreal Symphony Orchestra ( + Piano Concerto No. 3 and Bartók: Piano Concerto No. 3) EMI CLASSICS 556654-2) (1998) Martha Argerich (piano)/Alexander Rabinovich/Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana (rec. 2005) (included in collection: "Martha Argerich - Lugano Concertos") DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 4779884 (4 CDs) (2012) Vladimir Ashkenazy (piano)/Maurice Abravanel/Utah Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1963) ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3) KOCH SUISA INCD 7181 (1992) Vladimir Ashkenazy (piano)/André Previn/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2, 3, 4 and 5, Violin Concertos Nos. 1 and 2, Cello Concerto and Symphony- Concerto) DECCA TRIO 473259-2 (3 CDs) (2003) (original LP release: DECCA SXL 6767/LONDON CS 7062) (1975) Antonio Bacchelli (piano)/Wolfgang Schmid/Nuremberg Symphony Orchestra ( + Tedeschi: Fantasia Recitativo) FSM 68211 (LP) Jean-Efflam Bavouzet (piano)/Gianandrea Noseda/BBC Philharmonic ( + Piano Concertos Nos.