World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improvement of the Groundwater Monitoring Network in the Danube- Prut and Black Sea River Basin

European Union Water Initiative Plus for the Eastern Partnership Countries (EUWI+) Result 2 IMPROVEMENT OF THE GROUNDWATER MONITORING NETWORK IN THE DANUBE- PRUT AND BLACK SEA RIVER BASIN Moldova Final report; December 2020 Improvement of GW monitoring network Beneficiaries Agency of Geology and Mineral Resources (MD) Responsible EU member state consortium EUWI+ project leader Mr Alexander Zinke, Umweltbundesamt GmbH (AT) EUWI+ country representative in Moldova Mr Victor Bujac Responsible international thematic lead expert Andreas Scheidleder, Umweltbundesamt GmbH (AT) Responsible national thematic lead expert Boris Iurciuc, Agency of Geology and Mineral Resources (MD) Authors Aurelia Donos, Oleg Prodan, Maria Titovet, Tatiana Matrasilova, Nadejda Ivanova all State Enterprise Hydrogeological Expedition of Moldova (MD) Disclaimer: The EU-funded program European Union Water Initiative Plus for Eastern Partnership Countries (EUWI+) is im- plemented by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), both responsible for the implementation of Result 1, and an EU Mem- ber States Consortium comprising the Environment Agency Austria (UBA, Austria), the lead coordinator, and the International Office for Water (IOW, France), both responsible for the implementation of Results 2 and 3. The program is co-funded by Austria and France through the Austrian Development Agency and the French Artois-Picardie Water Agency. This document was produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Union or of the Governments of the Eastern Partnership Countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of, or sovereignty over, any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries, and to the name of any territory, city or area. -

10 Ri~ for Human Development

INTERNATIONAL PARTNERSHIP 10 RI~ FOR HUMAN DEVELOPMENT 26F Plaza Street, N E , Leesburg, Virgnia 20176, U S A. WINTER HEAT ASSISTANCE PROGRAM MOLDOVA USAID AGREEMENT NO. 121-A-00-99-00707-00 FINAL REPORT June 30, 1999 Tel (703) 443-2078, Fax. (703) 443-2012, E-mad mhd@erols corn TABLE OF CONTENTS Page # Report of Fuel Dellveries 1. Institutions which recelve fuel A. Hospitals ..... ....... 1 B. Boarding Schools & Orphanages .... ...... 2 C. Boarding Schools for Dlsabled .... ...... 3 D. Secondary Schools .......................... 3 E. Nurseries . ............................ .... 21 F. Pensloners & Vulnerable Famllles ...... 21 G. Other ................................. .. 40 H, Total Delivered ....................... 40 I. Summary of Dellverles by Categories ...... 41 J. Coverage Agalnst Heatmg Requlrements .... 41 Repalrs to Heatlng Systems ........... 42 Monitoring .......... ....... 43 Problems & How Problems were Addressed ........... 45 Outstanding Issues .......... 46 Cooperation wlth GOM .......... 46 Unforessen Matters ....... 47 Descrlbe any Matters/Problems Concerning Fuel Deliveries/Fuel Companies ....... 47 Number of Outstanding Fuel Companies Vouchers to be Paid ...... ....... 47 Other Comments ........... ...... 48 ATTACHMENT 1 Fuel Deliveries to Instltutlons ATTACHMENT 2: Coal Dellverles by Dlstrlct GR/AS Coal & Heatlng 011 for Instltutlons ATTACHMENT 3: Coal Dellverles by Dlstrlct - AS Coal for Households ATTACHMENT 4: Beneflclarles ATTACHMENT 5: Fuel Purchases ATTACHMENT 6: Coal Dellverles by Month ATTACHMENT 7. Payments -

Programul Electoral Al Candidatului Pentru Funcţia De Guvernator Al Găgăuziei IRINA VLAH

Alegerile Guvernatorului Găgăuziei din 30 iunie 2019 Programul electoral al candidatului pentru funcţia de Guvernator al Găgăuziei IRINA VLAH Implementarea programului regional "Acasă în Găgăuzia" Programul vizează întoarcerea şi acomodarea compatrioţilor în UTA Găgăuzia. Participanţii la program şi membrii familiilor acestora vor primi garanţii din partea autorităţilor regionale, sprijin financiar şi beneficii sociale: • Acordarea subvenţiilor în valoare de 40,000 de lei pentru fiecare familie care se întoarce la reşedinţa permanentă în Găgăuzia. • Furnizarea de stimulente pentru ca aceste familii să plătească impozite şi taxe locale. • Alocarea terenurilor pentru construirea şi dezvoltarea afacerilor proprii acestor familii în condiţii preferenţiale. • Asigurarea participării prioritare a familiilor care revin în Patria în programele de sprijin pentru întreprinderile mici şi mijlocii. • Acorda sprijinului familiilor în procesul de acomodare. Dezvoltarea industrială a regiunii • Crearea a 5,000 locuri de muncă noi, oferirea unui pachet social tuturor deţinătorilor a noilor locuri de muncă din sectorul real al economiei. • Creşterea salariului mediu în regiune la 10,000 lei. • Atragerea investiţiilor în volum anual de 100 de milioane de lei în zone economice libere – Comrat, Ceadîr-Lunga şi Vulcăneşti. • Deschiderea unui aeroport modern în Ceadîr-Lunga, care poate deservi zboruri internaţionale de mărfuri şi pasageri. • Construirea unei centrale electrice moderne în Vulcăneşti, care va asigura necesarul de energie electrică pentru regiune. • Acordarea subvenţiilor pentru toţi agenţii economici în valoare de 3,000 lei pentru fiecare nou loc de muncă creat. • Acordarea subvenţiilor pentru sprijinirea întreprinderilor mici şi mijlocii: până la 400 mii lei pentru fiecare solicitant. Volumul anual al granturilor va fi de 20 milioane de lei. alegeri.md Programul electoral al Irinei Vlah • Volumul fondului de sprijin pentru afaceri va fi majorat la 100 milioane de lei în 2023. -

From Ethnopolitical Conflict to Inter-Ethnic Accord in Moldova

Contents Preface and Acknowledgements 2 The Map of Moldova 4 Note on Terminology 5 Background 6 The Status of Transdniestria 8 Problems of Language and Education 13 The Ukrainian Minority 19 The Experience of Gagauzia 21 The Consequences of the Conflict for the Economy 23 Conclusions and Adoption of Recommendations 26 Recommendations of the Seminar (in English) 28 Recommendations of the Seminar (in Russian) 35 Documentary Appendix 41 Greetings from the OSCE Chairman-in-Office 42 Memorandum on the Bases for Normalization of Relations Between the Republic of Moldova and Transdniestria 44 Joint Statement of the Presidents of the Russian Federation and Ukraine in Connection with the Signing of the Memor- andum on the Bases for Normalization of the Relations Be- tween the Republic of Moldova and Transdniestria 47 Preface and Acknowledgements Following its opening in December 1996, the “European Centre for Minority Issues” (ECMI) initiated a series of conflict workshop-type meetings called ECMI Black Sea Seminars. The first event was a seminar entitled “From Ethnopolitical Conflict to Inter-Ethnic Accord in Moldova,” which took place from 12 to 17 September 1997 at Flensburg, Germany’s northernmost city and seat of ECMI, and at Bjerremark, Denmark—a former farm near the town of Tønder in Southern Jutland. Participants were diplomats, politicians, university professors and businessmen from the Transdniestrian and Gagauz parts of the Republic of Moldova as well as from the capital &KLÈLQsX (Kishinev in Russian). To facilitate the exchange of ideas and to revitalise the stalled negotiations between the parties to the conflict, experts in international law and diplomacy from the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the Council of Europe, and the Foreign Ministries of Denmark and Germany were also invited. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: ICR1969 IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION AND RESULTS REPORT (TF-94952) ON A Public Disclosure Authorized GRANT IN THE AMOUNT OF 12.5 MILLION EURO TO THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA FOR A Public Disclosure Authorized MOLDOVA REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT September 16, 2013 Public Disclosure Authorized Sustainable Development Department Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova Country Unit Europe and Central Asia Region CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective August 1, 2013) Currency Unit = Moldova Leu 1.00 = US$ 0.0809 US$ 1.00 = MDL 11.90 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AA Administrative Agreement AM Apele Moldovei CAS Country Assistance Strategy CDD Community Driven Development CPS Country Partnership Strategy CW Constructed Wetlands EC European Commission EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EU- NIF European Union Neighborhood Investment Facility Grant FSU Former Soviet Union GA Grant Agreement GEF Global Environmental Facility ICB International Competitive Bidding MRTI Ministry of Transport and Road Industry MSIF Moldova Social Investment Fund MTRI Ministry of Transport and Road Industry NDS National Development Strategy NEF National Ecological Fund NWSSP National Water Supply and Sanitation Program O&M Operation and Maintenance OM Operational Manual PIU Project Implementation Unit RSPS Moldova Road Sector Program Support SEA Sector Environmental Assessment SRA State Road Administration TFO Trust Fund Operational VOC Vehicle Operating Costs WWTP Wastewater Treatment Plant Vice President: Laura Tuck (Acting) Country Director: Qimiao Fan Sector Manager: Sumila Gulyani Project Team Leader: Ronnie W. Hammad ICR Team Leader: Paula Restrepo REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA MOLDOVA REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT CONTENTS Data Sheet A. -

Evaluation of the “Support to Agriculture and Rural Development” SARD Programme in ATU Gagauzia and Taraclia District and Neighbouring Communities

Evaluation of the “Support to Agriculture and Rural Development” SARD Programme in ATU Gagauzia and Taraclia district and neighbouring communities Report (III) Final Evaluation Prepared by Brigitte Mehlmauer-Larcher and Ghenadie Cojocau December 17th, 2018 1 Content List 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 4 2 Context of the Evaluation ............................................................................................................... 7 2.1 UNDP Country Programme document for the Republic of Moldova 2018-2020 .................... 7 2.2 European Neighbourhood Programme for Agriculture and Rural Development (ENPARD) ... 7 2.3 Country Strategy Documents.................................................................................................. 8 2.4 Donor projects (selection) ...................................................................................................... 9 3 Baseline situation ......................................................................................................................... 10 4 Methodological Approach ............................................................................................................ 12 4.1 Purpose of the evaluation .................................................................................................... 12 4.2 Scope of evaluation ............................................................................................................. -

List of Requirements and Technical Specifications 1. Introduction And

List of requirements and technical specifications 1. Introduction and objectives The major goal of the program is to promote SARD in ATU Gagauzia and Taraclia through opportunities to increase local development. One of the opportunities and/or components to support the development of local improvement projects/infrastructure development of small scale in rural areas of the region. This intervention intends, by the way, removing deficiencies, identified in the documents of the Republic of Moldova of strategic development of regions, as are the national development regional strategy for rural development and Agriculture, etc. Moldova 2020. 41 communities from UTA Gagauzia and Taraclia district will follow a participatory process of developing capacities. This action will facilitate the establishment of partnerships with local community groups, district and local public administrations, NGOs and other actors of local development. Technical assistance will be provided in the areas of competence of local public administration authorities (LPAS), such as utilities, health, education, social protection, and others. 20 town councils from UTA Gagauzia and r. Taraclia will receive technical and financial support to improve the quality of local services and rehabilitate infrastructure at the local level through the implementation of investment projects in communities. 2. The scope of work and the beneficiary communities 2.1 The contents of the work usually will provide the following types of works: constructions works, installation of equipment for pumping and filtering drinking water, water purification, automation, etc.; electrical works, installation of water and sanitation networks, landscaping works, testing and commissioning of systems for drinking water filtration and purification of wastewater, outdoor lighting system; and commissioning activities. -

CECE UTA GĂGĂUZIA № 36 Nr. D/O Denumirea Organului Electoral

CECE UTA GĂGĂUZIA № 36 DATELE DE CONTACT ALE CONSILIILOR ELECTORALE DE NIVELUL I CONSTITUITE PENTRU ORGANIZAREA ȘI DESFĂȘURAREA ALEGERILOR LOCALE GENERALE DIN DATA DE 20 OCTOMBRIE 2019 Nr. Denumirea Adresa sediului Graficul de recepționare a Persoana de Programul de activitate Contacte d/o organului electoral organului documentelor contact electoral pentru înregistrarea (numele, candidaților prenumele, funcţia) 1 СECE de nivelul I mun. Comrat, De la 11.09.2019-pînă la 19.09.2019 Președinte - Luni - Vineri 800-1700 Tel. 02982-44-46 Comrat nr. 36/1 str. Tretiacova,36 (inclusiv) Patutina Olga Pauza de masă 1200-1300 prîmăria Luni - Vineri 800-1600 078914524 Sîmbătă – Duminică Pauza de masă 1200-1300 900-1300 Sîmbătă - Duminică 900-1300 2 СECE de nivelul I mun. Ceadîr- De la 11.09.2019-pînă la 19.09.2019 Președinte - Luni - Vineri 800-1700 Tel. 02912-04-76 Ceadîr-Lunga Lunga, (inclusiv) Cebanova Olesea Fără Pauza de masă nr. 36/2 primăria, Luni - Vineri 800-1600 079503854 Sîmbătă – Duminică str. Lenin, 91 Fără pauza de masă 0 900-1300 Sîmbătă - Duminică 900-1200 3 СECE de nivelul I or.Vulcănești, De la 11.09.2019-pînă la 19.09.2019 Președinte - Luni - Vineri 800-1700 Tel. 02932-18-80 Vulcănești nr. 36/3 str. Lenin,75, (inclusiv) Baurciulu Nina Pauza de masă 1300-1400 consiliul raional Luni - Vineri 800-1600 069692333 Sîmbătă - Duminică Pauza de masă 1200-1300 900-1200 Sîmbătă - Duminică 900-1300 4 СECE de nivelul I s. Avdarma, De la 11.09.2019-pînă la 19.09.2019 Președinte - Luni - Vineri 800-1700 Tel. -

Project Concepts of the Regional Sector Programme

PROJECT CONCEPTS OF THE REGIONAL SECTOR PROGRAMME: Increasing the attractiveness of ATU Gagauzia for domestic and foreign tourists Authors: Angela Cascaval, Svetlana Lazar, Vitalii Chiurcciu, Svetlana Ghenova, Olga Aculova, Maria Nicolaev and Alla Cernioglo. Developed within EU funded project: “Technical Assistance for the integration of ATU Gagauzia in the national framework for regional development” – Contract № 2017/387 – 564 with the support of consortium: PLANET, AVENSA Consulting, INCOM Ltd. Project partners Executive Committee of Gagauzia Agency for Regional Development of Gagauzia This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union. CONCEPT “AT-PROLIN” 7 CONCEPT “AVDARMA” 17 CONCEPT “GAGAUZIA” DESTINATION MANAGEMENT ORGANISATION 25 CONCEPT “GAGAUZ HERITAGE” 33 CONCEPT “THE GAGAUZ CARPET” 43 CONCEPT “GEOPARK” 51 CONCEPT “CARBALIA ECO-PARK” 59 CONCEPT “MEDICAL AND HEALTH TOURISM” 67 CONCEPT “SUPPORT TO LOCAL ARTISANS” 76 CONCEPT “WINE ROUTE” 85 Summary As a result of analysis, in order to determine the degree of attractiveness of the region of ATU Gagauzia de- velopment, there were made general conclusions which became the basis for defining the objectives of the program to increase the tourist attractiveness of the region. • Tourism in Gagauzia is very poorly developed. The weak competition in tourist services market, lack of quality management of the development of tourist offer led to the fact that the ratio of price and quality of services makes them unattractive for tourists, mostly tourists spend no more than one day in Gagauzia. • The diaspora of Gagauzia sees the tourism potential of the region, based on the traditions and culture of the people, on the historical and natural heritage. -

Data Estimativă De Realimentare a Localităților Pe Nivelul De Tensiune 10Kv

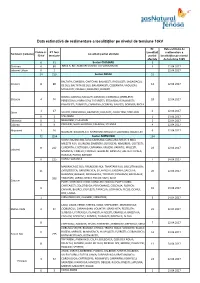

Data estimativă de realimentare a localităților pe nivelul de tensiune 10kV Nr. Data estimată de Fidere 6- PT fara Localitati realimentare a Sectoare (raioane) Localitati partial afectate 10 kV tensiune partial localităților pe nivelul afectate de tensiune 10kV 6 91 Sector CHISINAU 5 Chisinau 6 89 BRAILA; BIC; BUBUIECI;VADUL LUI VODA;BACIOI 5 22.04.2017 Ialoveni Urban 0 2 22.04.2017 14 210 Sector ORHEI 51 BALTATA; CIMISENI; ONITCANI; BALASESTI; RACULESTI; SAGAIDACUL Criuleni 8 80 DE SUS; BALTATA DE SUS; BALABANESTI; COSERNITA; VADULENI; 14 22.04.2017 MASCAUTI; CRUGLIC; BOSCANA; BUDESTI DOLNA; LOZOVA; MICAUTI; ZAMCIOJ; CIOBANCA; GREBLESTI; Straseni 4 74 PERESECINA; VORNICENI; TATARESTI; STEJARENI; ROMANESTI; 18 22.04.2017 PANASESTI; ZUBRESTI; CAPRIANA; SCORENI; GALESTI; GORNOE; RECEA 1 27 6 22.04.2017 Orhei SELISTE; PERESECINA; BRANESTI; VISCAUTI; CIOCILTENI; STEP-SOCI 0 2 STEJARENI 1 23.04.2017 Telenesti 0 2 NEGURENI; CIULUCANI 2 22.04.2017 Calarasi 0 9 PARCANI; SELISTEA NOUA; CALARASI; PITUSCA 4 22.04.2017 Nisporeni 1 16 GAURENI; BOLDURESTI; NISPORENI; GROZESTI; ZBEROAIA; BALANESTI 6 22.04.2017 72 1264 Sector ANENII NOI 154 ULMU; RAZENI; BALTATA; CARBUNA; GANGURA; MILESTII MICI; MILESTII NOI; CIGIRLENI; ZIMBRENI; SURUCENI; NIMORENI; COSTESTI; 8 222 CONDRITA; CHETROSU; CAPRIANA; VASIENI; VARATIC; MOLESTI; 23 22.04.2017 Ialoveni MISOVCA; HORESTI; HORASTI; GAURENI; DANCENI; BALTATI; TIPALA; HANSCA; PUHOI; BARDAR 0 215 HOMUTEANOVCA 7 24.04.2017 MARIANCA DE SUS; FIRLADENII NOI; TANATARII NOI; SALCUTA NOUA; 21 ZVIOZDOCICA; GRIGORIEVCA; STEFANESTI; -

Internal Dynamics of De Facto Statehood

DOI:10.17951/k.2017.24.1.115 ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS MARIAE CURIE-SKŁODOWSKA LUBLIN – POLONIA VOL. XXIV, 1 SECTIO K 2017 Institute of Political Science and International Affairs, John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, Poland MARCIN KOSIENKOWSKI The Gagauz Republic: Internal Dynamics of De Facto Statehood ABSTRACT The post-Soviet area is a home for a several de facto states, which are entities that resemble “normal” states but lack international recognition. This paper examines a historical and under-researched case study of the Gagauz Republic (Gagauzia), a de facto state that existed within Moldova between 1990 and 1995. Drawing on a new suite of sources – interviews, memoirs and journalism – it analyses the territorial, mil- itary, political, and socio-economic dimensions of the Gagauz de facto statehood, tracing how the Gagauz authorities proceeded in consolidating Gagauzia’s statehood through processes of state- and nation-building. This study concludes that the Gagauz leadership was moderately successful in its activities. Key words: the Gagauz Republic, Gagauzia, de facto state, state-building, nation-building INTRODUCTION The post-Soviet area is a home for six de facto states: Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karab- akh, South Ossetia, and Transnistria, as well as, in a historical perspective, Chechnya and the Gagauz Republic (Gagauzia). In short, de facto states resemble “normal” states except for one difference: they lack international recognition or enjoy it only * The author would like to thank all persons interviewed during field research conducted in Moldova and Ukraine. Many of interviews were facilitated by Elena Cuijuclu from the Comrat State University, for which she deserves sincere thanks. -

Towards Prospering Rural Areas

This project is funded by the European Union Towards Prospering Rural Areas SARD LEADER for community driven rural development initiatives in Gagauzia, Taraclia and neighboring rural communities REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA 2016-2018 represent local authorities, businesses AS E What is the SARD and civil society. LAGs decide on the R The LEADER Initiative territorial delineation of their activities, A Programme? LEADER (a French acronym meaning establish formal partnerships, prepare Links Between Actions for the and agree on integrated local rural URAL URAL The Support to Agriculture and Development of the Rural Economy) development strategies, and identify and R Rural Development (SARD) is an EU initiative, a method and implement local development actions. programme instrument to support ING ING Programme is a three-year R initiative of the European locally-driven rural development PE Union implemented by UNDP interventions to reinvent rural areas and create local jobs. LEADER in Moldova ROS in the Republic of Moldova. The frst LEADER programme started in Local implementation of the SARD The main objective of the EU Member Countries in 1991. LEADER Initiative started with an programme is to foster Because of its development efciency awareness-raising campaign aimed at confdence-building by and popularity in rural communities, mobilizing local partners in targeted LEADER still exists in the EU. It has 26 regions. The result was the creation of TOWARDS P targeting regions and territorial years of experience in thousands of eight local development partnerships, administrative units with special rural areas where the programme has covering the greater part of the rural status. successfully been implemented.