Chelsea Biondodillo • “Burying the Prairie”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minnesota Army National Guard Camp Ripley Training Center and Arden Hills Army Training Site

MINNESOTA ARMY NATIONAL GUARD CAMP RIPLEY TRAINING CENTER AND ARDEN HILLS ARMY TRAINING SITE 2013 CONSERVATION PROGRAM REPORT Cover Photography: Fringed gentian (Gentiana crinita), Camp Ripley Training Center, 2011, Laura May, Camp Ripley Volunteer. Minnesota Army National Guard Camp Ripley Training Center and Arden Hills Army Training Site 2013 Conservation Program Report January 1 – December 31, 2013 Division of Ecological and Water Resources Minnesota Department of Natural Resources for the Minnesota Army National Guard Compiled by Nancy J. Dietz, Animal Survey Assistant Brian J. Dirks, Animal Survey Coordinator MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES CAMP RIPLEY SERIES REPORT NO. 23 ©2014, State of Minnesota Contact Information: MNDNR Information Center 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4040 (651) 296-6157 1-888-MINNDNR (646-6367) Telecommunication Device for the Deaf (651) 296-5484 1-800-657-3929 www.dnr.state.mn.us This report should be cited as follows: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources and Minnesota Army National Guard. 2014. Minnesota Army National Guard, Camp Ripley Training Center and Arden Hills Army Training Site, 2013 Conservation Program Report, January 1-December 31, 2013. Compiled by Nancy J. Dietz and Brian J. Dirks, Camp Ripley Series Report No. 23, Little Falls, MN, USA. 205 pp. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ...................................................................................................................................... I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... -

Ofcanada Part13

THE INSECTS ANDARAOHNIDS OFCANADA PART13 The ofca,.m'ffitrslP; Coleo r* SgHHy'" THE INSECTS ANDARACHNIDS OFCANADA t%RT13 The Carrion Beetles of Canada and Alaska Coleoptera Silphidae and Agyrtidae Robert S. Andersonl and Stewart B. Peck2 Biosystematics Research Institute Ottawa, Ontario Research Branch Agriculture Canada Publication 1778 1985 rUniyersity of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta 2Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario oMinister of Supply and Services Canada 1985 Available in Canada through Authorized Bookstore Agents and other bookstores or by mail from Canadian Government Publishing Centre Supply and Services Canada Ottawa, Canada KIA 0S9 Catalogue No. A42-42,21985-l3E Canada: $7.00 ISBN 0-662-11752-5 Other Countries: $8.40 Price subject to change without notice Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Anderson, Robert Samuel The carrion beetles of Canada and Alaska (Coleoptera: Silphidae and Agyrtidae) (The Insects and arachnids of Canada, ISSN 0706-7313 ; pt. 13) (Publication ;1778) Includes bibliographical references and index. l. Silphidae. 2. Beetles - Canada. 3. Beetles -- Alaska. I. Peck, Stewart B. II. Canada. Agricul- ture Canada. Research Branch. III. Title. IV. Series. V. Series: Publication (Canada. Agri- culture Canada). English ; 1778. QL596.S5A5 1985 595.76 C85-097200-0 The Insects and Arachnids of Canada Part l. Collecting, Preparing, and Preserving Insects, Mites, and Spiders, compiled by J. E. H. Martin, Biosystematics Research Institute, Ottawa, 1977. 182 p. Price: Canada $3.50, other countries $4.20 (Canadian funds). Cat. No. A42-42/1977 -1. Partie 1. R6colte, prdparation et conservation des Insectes, des Acariens et des Araign6es, compil6 par J.E.H. Martin, Institut de recherches biosyst6- matiques, Ottawa, 1983. -

Key to the Carrion Beetles (Silphidae) of Colorado & Neighboring States

Key to the carrion beetles (Silphidae) of Colorado & neighboring states Emily Monk, Kevin Hinson, Tim Szewczyk, Holly D’Oench, and Christy M. McCain UCB 265, Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, and CU Museum of Natural History, Boulder, CO 80309, [email protected], [email protected] Version 1 posted online: March 2016 This key is based on several identification sources, including Anderson & Peck 1985, De Jong 2011, Hanley & Cuthrell 2008, Peck & Kaulbars 1997, Peck & Miller 1993, and Ratcliffe 1996. We include all species known from Colorado and those in the surrounding states that might occur in Colorado. Of course, new species may be detected, so make sure to investigate unique individuals carefully. We have included pictures of each species from specimens of the Entomology collection at the CU Museum of Natural History (UCM), the Colorado State C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity (GMAD), and the Florida State Collection of Arthropods (FSCA). A glossary of terms, a list of the states where each species has been detected, and references can be found after the key. We would appreciate reports of omitted species or species from new localities not stated herein. First step—ID as a silphid: Large size, body shape, and antennal club are usually distinctive. Body usually 10-35 mm, moderately to strongly flattened. Elytra broad toward rear, either loosely covering abdomen or short, exposing 1-3 segments. Antennae often ending in a hairy, three-segmented club, usually preceded by two or three enlarged but glabrous segments (subfamily Silphinae) or antennomeres 9-11 lammellate (subfamily Nicrophorinae). Black, often with red, yellow, or orange markings. -

An All-Taxa Biodiversity Inventory of the Huron Mountain Club

AN ALL-TAXA BIODIVERSITY INVENTORY OF THE HURON MOUNTAIN CLUB Version: August 2016 Cite as: Woods, K.D. (Compiler). 2016. An all-taxa biodiversity inventory of the Huron Mountain Club. Version August 2016. Occasional papers of the Huron Mountain Wildlife Foundation, No. 5. [http://www.hmwf.org/species_list.php] Introduction and general compilation by: Kerry D. Woods Natural Sciences Bennington College Bennington VT 05201 Kingdom Fungi compiled by: Dana L. Richter School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science Michigan Technological University Houghton, MI 49931 DEDICATION This project is dedicated to Dr. William R. Manierre, who is responsible, directly and indirectly, for documenting a large proportion of the taxa listed here. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 5 SOURCES 7 DOMAIN BACTERIA 11 KINGDOM MONERA 11 DOMAIN EUCARYA 13 KINGDOM EUGLENOZOA 13 KINGDOM RHODOPHYTA 13 KINGDOM DINOFLAGELLATA 14 KINGDOM XANTHOPHYTA 15 KINGDOM CHRYSOPHYTA 15 KINGDOM CHROMISTA 16 KINGDOM VIRIDAEPLANTAE 17 Phylum CHLOROPHYTA 18 Phylum BRYOPHYTA 20 Phylum MARCHANTIOPHYTA 27 Phylum ANTHOCEROTOPHYTA 29 Phylum LYCOPODIOPHYTA 30 Phylum EQUISETOPHYTA 31 Phylum POLYPODIOPHYTA 31 Phylum PINOPHYTA 32 Phylum MAGNOLIOPHYTA 32 Class Magnoliopsida 32 Class Liliopsida 44 KINGDOM FUNGI 50 Phylum DEUTEROMYCOTA 50 Phylum CHYTRIDIOMYCOTA 51 Phylum ZYGOMYCOTA 52 Phylum ASCOMYCOTA 52 Phylum BASIDIOMYCOTA 53 LICHENS 68 KINGDOM ANIMALIA 75 Phylum ANNELIDA 76 Phylum MOLLUSCA 77 Phylum ARTHROPODA 79 Class Insecta 80 Order Ephemeroptera 81 Order Odonata 83 Order Orthoptera 85 Order Coleoptera 88 Order Hymenoptera 96 Class Arachnida 110 Phylum CHORDATA 111 Class Actinopterygii 112 Class Amphibia 114 Class Reptilia 115 Class Aves 115 Class Mammalia 121 INTRODUCTION No complete species inventory exists for any area. -

Plum Island Biodiversity Inventory

Plum Island Biodiversity Inventory New York Natural Heritage Program Plum Island Biodiversity Inventory Established in 1985, the New York Natural Heritage NY Natural Heritage also houses iMapInvasives, an Program (NYNHP) is a program of the State University of online tool for invasive species reporting and data New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry management. (SUNY ESF). Our mission is to facilitate conservation of NY Natural Heritage has developed two notable rare animals, rare plants, and significant ecosystems. We online resources: Conservation Guides include the accomplish this mission by combining thorough field biology, identification, habitat, and management of many inventories, scientific analyses, expert interpretation, and the of New York’s rare species and natural community most comprehensive database on New York's distinctive types; and NY Nature Explorer lists species and biodiversity to deliver the highest quality information for communities in a specified area of interest. natural resource planning, protection, and management. The program is an active participant in the The Program is funded by grants and contracts from NatureServe Network – an international network of government agencies whose missions involve natural biodiversity data centers overseen by a Washington D.C. resource management, private organizations involved in based non-profit organization. There are currently land protection and stewardship, and both government and Natural Heritage Programs or Conservation Data private organizations interested in advancing the Centers in all 50 states and several interstate regions. conservation of biodiversity. There are also 10 programs in Canada, and many NY Natural Heritage is housed within NYS DEC’s participating organizations across 12 Latin and South Division of Fish, Wildlife & Marine Resources. -

Classification of Forensically-Relevant Larvae According to Instar in A

Forensic Sci Med Pathol DOI 10.1007/s12024-016-9774-0 TECHNICAL REPORT Classification of forensically-relevant larvae according to instar in a closely related species of carrion beetles (Coleoptera: Silphidae: Silphinae) 1,2 1 Katarzyna Fra˛tczak • Szymon Matuszewski Accepted: 14 March 2016 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Carrion beetle larvae of Necrodes littoralis Introduction (Linnaeus, 1758), Oiceoptoma thoracicum (Linnaeus, 1758), Thanatophilus sinuatus (Fabricius, 1775), and Age determination of beetle larvae is a difficult task [1]. It Thanatophilus rugosus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Silphidae: Sil- can be estimated from length, weight, or developmental phinae) were studied to test the concept that a classifier of stage [2–4]. Under controlled laboratory conditions, when the subfamily level may be successfully used to classify insects may be continuingly monitored, it is usually beyond larvae according to instar. Classifiers were created and doubt what stage of development specimen represents, as validated using a linear discriminant analysis (LDA). LDA ecdysis is confirmed by the presence of exuvia [5]. In the generates classification functions which are used to calcu- practice of forensic entomology developmental stage of an late classification values for tested specimens. The largest immature insect sampled from a body has to be classified value indicates the larval instar to which the specimen according to instar using different methods. In the case of should be assigned. Distance between dorsal stemmata and forensically important flies, instar classification is easy due width of the pronotum were used as classification features. to robust qualitative diagnostic features [6, 7]. -

Identification, Distribution, and Adult Phenology of the Carrion Beetles (Coleoptera: Silphidae) of Texas

Zootaxa 3666 (2): 221–251 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3666.2.7 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:4951C68A-93C4-4777-B7D4-D7D657AE1DBC Identification, distribution, and adult phenology of the carrion beetles (Coleoptera: Silphidae) of Texas PATRICIA L. MULLINS1, EDWARD G. RILEY2 & JOHN D. OSWALD2 1Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Organismal Biology, 251 Bessey Hall, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa 50010. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Entomology, Texas A&M University, Minnie Belle Heep Center, TAMU 2475, College Station, Texas 77845. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract The carrion beetles (Coleoptera: Silphidae) of Texas are surveyed. Thirteen of the 14 species, and five of the six genera, of this ecologically and forensically important group of scavengers that have previously been reported from Texas are confirmed here based on a study of 3,732 adult specimens. The one reported, but unconfirmed, species, Oxelytrum discicolle, was probably based on erroneous label data and is excluded from the Texas fauna. Two additional species, Nicrophorus sayi and N. investigator are discussed as possible, but unconfirmed, components of the fauna. Taxonomic diagnoses, Texas distribution range maps, seasonality profiles, and biological notes are presented for each confirmed species. The confirmed Texas silphid fauna of 13 species comprises 43% of the 30 species of this family that are known from America north of Mexico. The highest richness (11 species) is found in the combined Austroriparian and Texan biotic provinces of eastern Texas. -

Burying Beetles

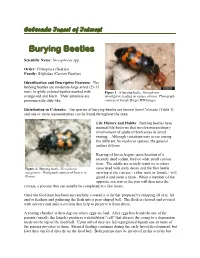

Colorado Insect of Interest Burying Beetles Scientific Name: Nicrophorus spp. Order: Coleoptera (Beetles) Family: Silphidae (Carrion Beetles) Identification and Descriptive Features: The burying beetles are moderate-large sized (25-35 mm), brightly colored beetles marked with Figure 1. A burying beetle, Nicrophorus orange-red and black. Their antennae are investigaror, feeding on a piece of meat. Photograph pronouncedly club-like. courtesy of Joseph Berger/IPM Images Distribution in Colorado: Ten species of burying beetles are known from Colorado (Table 1) and one or more representatives can be found throughout the state. Life History and Habits: Burying beetles have unusual life histories that involve extraordinary involvement of adults of both sexes in larval rearing. Although variations may occur among the different Nicrophorus species, the general outline follows. Rearing of larvae begins upon location of a recently dead rodent, bird or other small carrion item. The adults are acutely sensitive to odors Figure 2. Burying beetle, Nicrophorus associated with early decay and the first beetle marginatus. Photograph courtesy of Insects in arriving at the carcass - either male or female - will Kansas. guard it and await a mate. When a member of the opposite sex arrives the pair will then inter the carcass, a process that can usually be completed in a few hours. Once the food item has been successfully covered it is further prepared by stripping all skin, fur and/or feathers and gathering the flesh into a pear-shaped ball. The flesh is chewed and covered with salivary and anal secretions that help to preserve it from decay. A rearing chamber is then dug out where eggs are laid. -

Anthony Zhao, University of Maryland. Species Diversity and Community Similarity of Carrion Beetles Along an Urban-Rural Gradient

Anthony Zhao, University of Maryland. Species Diversity and Community Similarity of Carrion Beetles Along an Urban-Rural Gradient. Mentor: Dr. Jason Munshi-South Abstract: Habitat fragmentation resulting from urbanization is a major threat to carrion beetle (Coleoptera: Silphidae) communities in the Northeastern United States. This study examined species richness, diversity, and community similarity of carrion beetles along an urban-rural gradient in the New York City metropolitan area. Carrion beetles were trapped and collected at 12 field sites. We captured eight species in total, the most common being Nicrophorus tomentosus, Oiceoptoma noveboracense, and Nicrophorus orbicollis. O. noveboracense was found predominantly in urban and suburban areas, earlier during the summer. Necrophila americana was only found in suburban and rural areas later during the summer, Nicrophorus defodiens predominantly in rural areas, and Nicrophorus sayi only in rural areas. We calculated both species richness and Simpson’s reciprocal diversity index for all sites, and examined their association with urbanization using linear regression. We also examined community similarity between all pairs of sites. Additionally, the carrion beetle community at the Louis Calder Center in Armonk, New York was compared with the community observed in a past survey. Urbanization was not significantly associated with either species richness or diversity. We determined that community similarity was not strongly associated with position along the gradient, and it showed some variation between habitat groups. We also reported that the carrion beetle community at the Calder Center has changed considerably, likely as a result of increased local development. These findings indicate that urban forest fragments may be able to support relatively high carrion beetle diversity, and can be used to guide future studies in urbanization and arthropod communities. -

Urban Forests Sustain Diverse Carrion Beetle Assemblages in the New York City Metropolitan Area

Urban forests sustain diverse carrion beetle assemblages in the New York City metropolitan area Nicole A. Fusco1, Anthony Zhao2 and Jason Munshi-South1 1 Louis Calder Center–Biological Field Station, Fordham University, Armonk, NY, USA 2 Department of Entomology, University of Maryland at College Park, College Park, MD, USA ABSTRACT Urbanization is an increasingly pervasive form of land transformation that reduces biodiversity of many taxonomic groups. Beetles exhibit a broad range of responses to urbanization, likely due to the high functional diversity in this order. Carrion beetles (Order: Coleoptera, Family: Silphidae) provide an important ecosystem service by promoting decomposition of small-bodied carcasses, and have previously been found to decline due to forest fragmentation caused by urbanization. However, New York City (NYC) and many other cities have fairly large continuous forest patches that support dense populations of small mammals, and thus may harbor relatively robust carrion beetle communities in city parks. In this study, we investigated carrion beetle community composition, abundance and diversity in forest patches along an urban- to-rural gradient spanning the urban core (Central Park, NYC) to outlying rural areas. We conducted an additional study comparing the current carrion beetle community at a single suburban site in Westchester County, NY that was intensively surveyed in the early 1970's. We collected a total of 2,170 carrion beetles from eight species at 13 sites along this gradient. We report little to no effect of urbanization on carrion beetle diversity, although two species were not detected in any urban parks. Nicrophorus tomentosus was the most abundant species at all sites and seemed to dominate the urban communities, potentially due to its generalist habits and shallower burying depth Submitted 3 October 2016 compared to the other beetles surveyed. -

(Diptera: Calliphoridae) and Introduced Fire Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Solenopsis Invicta and S

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 11-25-2020 Roles and interaction of blow flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) and introduced fire ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Solenopsis invicta and S. invicta x richteri) in carrion decomposition in the southeastern United States Grant De Jong Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td Recommended Citation De Jong, Grant, "Roles and interaction of blow flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) and introduced fire ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Solenopsis invicta and S. invicta x richteri) in carrion decomposition in the southeastern United States" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 3839. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td/3839 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Template A v4.0 (beta): Created by L. Threet 01/2019 Roles and interaction of blow flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) and introduced fire ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Solenopsis invicta and S. invicta x richteri) in carrion decomposition in the southeastern United States By TITLE PAGE Grant Douglas De Jong Approved by: Jerome Goddard (Major Professor) Florencia Meyer (Co-Major Professor) Jeffrey W. Harris Natraj Krishnan Gerald T. Baker Kenneth Willeford (Graduate Coordinator) Scott T. -

Coleoptera: Silphidae) STEVENW

15 August 1995 JOURNAL OF THE KANSAS ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY 68(2), 1995, pp. 214-223 Diversity, Habitat Preferences, and Seasonality of Kansas Carrion Beetles (Coleoptera: Silphidae) STEVENW. LINGAFELTER Snow Entomological Museum, Snow Hall, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045 ABSTRACT: Pitfall trapping, blacklighting, and examinâtion of institutional collections produced records for 13 species of Silphidae in Kansas: Necrodes surinamensis (Fabricius), Necrophila americana (Linnaeus), Nicrophorus americanus Olivier, Ni. carolinus (Lin- naeus), Ni. marginatus Fabricius, Ni. mexicanus Matthews, Ni. orbicollis (Say), Ni. pus- tulatus Herschel, Ni. tomentosus Weber, Oiceoptoma inaequale (Fabricius), 0. novebora- cense (Forster), Thanatophilus lapponicus (Herbst), and T. truncatus (Say). No current populations of the federally endangered silphid, Ni. americanus or Ni. mexicanus were documented in Kansas, and records for both species are more than 50 years old. Data based on 2007 specimens resulting from 1709 pitfall trapnights in 23 Kansas counties are standardized and used in an assessment of habitat preferences and seasonality among the encountered taxa. Four species (Ni. carolinus, Ni. marginatus, T. lapponicus, and T. trun- catus) are nearly restricted to open prairies with sandy soil, 2 species (Ne. americana and 0. noveboracense) are dominant in woodlands, and 3 species (Ni. orbicollis, Ni. pustulatus, and 0. inaequale) occur in both wooded and open habitats. Necrodes surinamensis and Ni. pustulatus have bimodal peaks of activity in Kansas. Adults of 0. inaequale and 0. noveboracense were not captured in Kansas after mid-summer. Necrophila americana, Ni. marginatus, Ni. orbicollis, and Ni. tomentosus occur in Kansas from spring to late summer. The purpose of this study is to reveal current pattems of diversity, distribution, habitat preferences, and seasonality for Kansas carrion beetles (Coleoptera: Sil- phidae).