How to Train Your Rower" for All of the Rowers and Coaches out There Who Aren't Necessarily As Familiar with the Lifts As They Are the Technique of Rowing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shoulder Attack

Grab & Go Workouts Presented by the Fitness Centers Created by: Natalie Horton Name of Workout: Shoulder Attack Primary Target Area: Shoulders Approximate Time: ~ 45 minutes to an hour Skill Level: Intermediate Warm-up: 5 – 10 minutes on any cardio machine, with 2 sets of 10 reps of banded front pulls and banded pull apart Exercise Routine Exercise Sets Reps Rest Notes Super set: No rest between exercises, rest after • External rotations 3 12 1 min completing both. • Half Arnolds 3 12 See diagram. Seated Overhead Press 4 10-12 45 sec – DB start at shoulder height, palms 1 min facing forward. Underhand Grip Front 3 12 45 sec – See diagram. Raises 1 min Lateral/Front Raises 3 40 45 sec – Hold one arm lateral in a static 1 min position while doing 10 front raises, repeat for other arm. Hold one arm front in a static position while doing 10 lateral raises, repeat for other arm. Single Arm Upright Row 3 12 (each 45 sec – See diagram. arm) 1 min Plate Front Raises 3 12 45 sec – Have feet slightly apart. 1 min Bus Drivers 3 10 (each 45 sec – See diagram. Rotate slowly. way) 1 min Cool Down: 5 minutes of walking (on incline), followed by upper arm stretching. Additional Notes: Feel free to change the reps/rest to what works best for you if it is too easy or to hard. Also have fun with it! Questions or Comments? Please e-mail [email protected] Sample Diagrams Banded Face Pulls Banded Pull Apart Underhand Grip Front Raise Bus Drivers External Rotations Half Arnolds Single Arm Upright Row . -

Press by Bill Starr

Starting Strength The Olympic-Style Press by Bill Starr My purpose in writing this article is twofold: to explain how to do the type of press known as the Olympic-style press and to defend all forms of pressing. The exercise has been maligned in the past and is once again under fire. In both instances, the criticism is ungrounded. The overhead press has always been a primary exercise for those who were involved in any form of weight training. Bodybuilders did lots of overhead presses to build more muscular shoulders and arms. Strength athletes included heavy presses in their routines in order to gain more power in their upper bodies, and Olympic weightlifters spent a third of their training time working on the press since it was part of the sport’s agenda. Even those who just trained for overall fitness did presses. It was the standard of upper body strength and, to most, also the gauge of how strong a person was. When someone wanted to know how strong you were, he asked, “How much can you press?” There were many different ways people pressed. Some did them in a very strict manner, with upper bodies erect and the bar traveling in a straight line from shoulders to lockout. Others would drive the bar upward and immediately lay back to finish the lift. Yet others would wait until the bar hit the mid-point of the movement before laying back just a bit. The New Orleans lifters Louis Riecke, Dr. John Gourgott, and Walter Imahara, used a unique style of pressing that no one else could emulate. -

Vertical Pushing Overview and Key Points

Vertical Pushing Overview and Key Points Key Notes for Shoulder Pain 1. Overhead press is generally one of the toughest things to perform when painful. It often needs to be taken out of the program temporarily for painful shoulders 2. If you can’t find a pain free press variation, rowing variations are generally well tolerated and serve as a good modification. 3. Pressing in a more horizontal plane (bench press) may be better tolerated than overhead press. 4. Reducing the load, slowing down the speed of the lift and increasing the reps can some- times allow us to still get a training effect and eliminate pain. Accessory Shoulder Health Work These exercises can be added to someone’s training program when they are having pain when press- Vertical Pushing - Key Points Pushing - Key Vertical ing overhead. 1. Foam roll lats and teres major x 10 passes 2. Thoracic spine foam rolling x 10 reps 3. Ring rows 3 x 8-12 reps 4. Side lying external rotation 3 x 8-12 reps 5. Scaption / front raise 3 x 8-12 reps **Perform 2-3 x per week in addition to regular programming Key Notes for Low Back Pain 1. Attempt to eliminate pain by modifying technique, in some athletes this won’t work so utilize the modification list below 2. Some athletes won’t be able to be coached into good positions simply due to tightness. If an athlete can’t correct movement with cues and the load is manageable you can begin thinking they may have mobility restrictions 3. -

15 Minute Trail Rider Tune up Workout Programs Manual

15 Minute Trail Rider Tune Up Workouts www.bikejames.com/15M-TRTU 15 Minute Trail Rider Tune Up Workout Programs Manual Copyright © 2015 - MTB Strength Training Systems - All Rights Reserved Worldwide. 1 15 Minute Trail Rider Tune Up Workouts www.bikejames.com/15M-TRTU WARNING: This eBook is for your personal use only. You may NOT Give Away, Share Or Resell This Intellectual Property In Any Way All Rights Reserved Copyright © 2015 – MTB Strength Training Systems. All rights are reserved. You may not distribute this report in any way. You may not sell it, or reprint any part of it without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review. Copyright © 2015 - MTB Strength Training Systems - All Rights Reserved Worldwide. 2 15 Minute Trail Rider Tune Up Workouts www.bikejames.com/15M-TRTU Disclaimer You must get your physician's approval before beginning this exercise program. These recommendations are not medical guidelines but are for educational purposes only. You must consult your physician prior to starting this program or if you have any medical condition or injury that contraindicates physical activity. This program is designed for healthy individuals 18 years and older only. The information in this report is meant to supplement, not replace, proper exercise training. All forms of exercise pose some inherent risks. The editors and publishers advise readers to take full responsibility for their safety and know their limits. Before practicing the exercises in this book, be sure that your equipment is well-maintained, and do not take risks beyond your level of experience, aptitude, training and fitness. -

Periodization and Exercise Selection

RESISTANCE TRAINING Workout Options and Program Periodization BASIC RULES FOR EXERCISE SELECTION AND ORGANIZATION: When selecting exercises for a particular muscle group, one must consider a number of factors to ensure the safety of the musculature and joints involved in the movement, to attain the temporary failure condition for the muscles involved to promote continued progress and to ensure activation of the desired muscle groups. These rules include: A. Exercises for problem muscle groups should be performed at the beginning of the workout to prevent their omission from the workout. This organization also allows the weight trainer to address these exercises with the greatest amount of energy available. This should help to maximize one’s efforts and, ultimately, one’s progress. B. Exercises for large muscle groups should always be addressed before those for small muscle groups. Ex.: pectorals, and depending upon the specific exercise selected, shoulders before triceps; latissimus dorsi and trapezius before biceps, quadriceps before gastrocnemius (calves). C. Multiple-joint exercises should always be performed before isolation exercises. Multiple-joint exercises involve the large muscle groups of the body, i.e. the pectorals, latissimus dorsi, trapezius, quadriceps (when assisted by the gluteal and/or hip flexor groups), hamstrings and the deltoids. These exercises typically have a “last name” of: press, pull, row, squat or lunge. Single-joint exercises utilize only one joint and usually involve such muscle groups as the deltoids (with no assistance from the triceps), the triceps, biceps, the quadriceps or hamstrings (when not assisted by the gluteal or hip flexor groups). These exercises typically have a “last name” of: extension, curl, flye, raise, pressdown or pulldown. -

Shoulder Press, Push Press, Push Jerk--The Overhead Lifts

January 2003 THECrossFit® Journal © 2003 All rights reserved "mess you up" Shoulder Press, Push Press, Push Jerk – The Overhead Lifts Introduction Learning the progression of lifts that moves from the shoulder press, to the push press, to the push jerk has long been a staple of the CrossFit regimen. This progression offers the opportunity to acquire some essential motor recruitment patterns found in sport and life (functionality) while greatly improving strength in the “power zone” and upper body. In terms of power zone and functional recruitment patterns, the push press and push jerk have no peer among the other presses like the “king” of upper body lifts, the bench press. As the athlete moves from shoulder press, to push press, to push jerk, the importance of core to extremity muscle recruitment is learned and reinforced. This concept alone would justify the practice and training of these lifts. Core to extremity muscular recruitment is foundational to the effective and efficient performance of athletic movement. The most common errors in punching, jumping, throwing, and a multitude of other athletic movements typically express themselves as a violation of this concept. Because good athletic movement begins at the core and radiates to the extremities, core strength is absolutely essential to athletic success. The region of the body from which these movements emanate, the core, is often referred to as the “power zone.” The muscle groups comprising the “power zone” include the hip flexors, hip extensors (glutes and hams), spinal erectors, and quadriceps. These lifts are enormous aids to developing the power zone. Additionally, the advanced elements of the progression, the push press and jerk, train for and develop power and speed. -

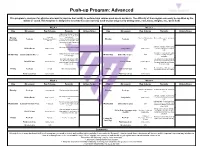

Push-Up Program: Advanced

Push-up Program: Advanced This program is designed for athletes who want to improve their ability to perform high volume push-ups in workouts. The difficulty of the program can easily be modified by the athlete or coach. This template is designed to be printed so you can keep track of your progress by writing notes, reps, times, weights, etc.. Good luck! Week 1 Week 2 Day Movement Rep Scheme Remarks Athlete Notes Day Movement Rep Scheme Remarks Athlete Notes Make a note of your PR set of push ups. Rest as needed after 1 max set the max set. Monday 10 sets of 10 unbroken Rest as little as needed between Push-ups Rest as needed, then For the 50 reps, complete this Push-ups Monday reps sets (Test Day) 50 reps in as few sets as possible. Note the number of sets it takes you to complete. :30 front, :30 right, :30 left without One "rep" is one back-and-forth Hollow Rocks 4x30 seconds 3-way planks 3x90 seconds rest. Rest 1-2 minutes between rock. sets. The goal here is to get time under Heavy, but perfect reps. Elbows Dumbbell Bench Presses 4x10 Barbell Bench press 3x10 tension. Loading should be Wednesday in, neutral grip. Wednesday moderate. Overhand, wide grip on each Use a barbell or rings, and prop set. Record your biggest set your feet up such that they are at Strict Pull-ups 4 max rep sets Inverted Rows 4 max rep sets and total reps. Rest as needed the same height as your hands. -

Equestrian Athlete Fitness365 Workouts: Module 5

EQUESTRIAN ATHLETE FITNESS365 WORKOUTS: MODULE 5 “Resisting Rotation” Workout Schedule Resistance Pilates/Yoga Metabolic Cardio/Restorative Conditioning Monday Resistance 9 Optional: Hill Sprints: Find a 50- 75 m (150-200 ft) on a 10-20% incline. Sprint up, walk down 12 times. Tuesday Pilates #5 Wednesday Metabolic Body Mobilization Conditioning 5 Drills – Hip distraction Thursday Resistance 10 15-25 minutes yoga (pick your programs) Friday Metabolic Body Mobilization Conditioning 7 Drills – Shoulder ER, Spiderman lunges Saturday 15-25 minutes 30-60 minute yoga (pick your leisure walk or low programs) intensity barn work Sunday 30-60 minute leisure walk or low intensity barn work Complete the Fitness Tests the first week of each module. Track your results and see how you improve over time. Commit to being consistent and you’ll get stronger! EAF365 Module 5 , Page | 1 Fitness challenges Complete these challenges the first week of each module in the Equestrian Athlete program. Track your scores and celebrate progress! When you do the exercises, go to muscle failure. This means you cannot do another complete repetition or hold the pose for any longer. Wall Squat How to do it: Stand with your back to a smooth wall with your feet at shoulder width and about one foot away from the wall. Keep your back firmly against the wall and slowly slide down the wall until your knees and hips are both at 90-degree angles. Make sure that your knees track over your toes. Hold this position until start to slide down and cannot maintain proper form. Many people say they can hold a longer wall squat but aren’t squatting deep enough. -

12 Week Off Season Strength and Power Program for Basketball Players

12 WEEK OFF SEASON STRENGTH AND POWER PROGRAM FOR BASKETBALL PLAYERS Important No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the author. The exercise information presented on these pages is intended as an educational resource and is not intended as a substitute for proper medical advice. Consult your physician or health care professional before performing any of the exercises described on these pages or any exercise technique or regimen, particularly if you have chronic or recurring medical conditions. Discontinue any exercise that causes you pain or severe discomfort and consult a medical expert. Neither the author nor advertisers of this manual make any warranty of any kind in regard to the content of the information presented and accept no responsibility for its misuse. Additional Resources For additional basketball specific strength & conditioning resources, please visit: Stronger Team | Alan Stein’s Blog: http://Blog.StrongerTeam.com Training Products, Guides, Workouts, Programs: http://Shop.StrongerTeam.com Stronger Team Information, Schedules, Articles, Services: http://www.StrongerTeam.com Free Training Videos: http://www.youtube.com/StrongerTeamDotCom Authors Alan Stein Blair O’Donovan Steve Tikoian © 2010 Stronger Team, LLC | All Rights Reserved Stronger Team, LLC 12 WEEK OFF SEASON STRENGTH AND POWER PROGRAM FOR BASKETBALL PLAYERS Introduction Congratulations on taking an important step in maximizing your potential for success on the basketball court. Your effort and dedication, combined with the information in this program, will help you implement a sound and productive off-season strength training and power program. -

Mix 'N' Match Quick

GET MOVING Ideas Mix ‘N’ Match It’s easy to get 15 minutes of movement today. Just choose as many activities as you like, and watch them add up. Remember – you don’t have to do 15 minutes in one session. Every minute of movement – all day long – counts. Quick ‘N’ Easy Here are some things we like for mini-movement breaks during our day. Or come up with your own! 1 MINUTE F 30 jumping jacks (harder) or 30 big arm F Sit down and stand up from a chair 20 times circles while walking (easier) (if you want to make this harder, use a lower F Climb a few flights of stairs (easier) or seat or a step; or come up on your toes and climb a few flights of stairs facing sideways reach for the sky with your arms each time (harder). As you get fitter, add a little speed. you stand up) F Walk forward or sideways by taking 15 to F Squat down, pick up, and carry some 20 big steps with each leg; or walk with feet laundry, groceries, other bags, and/or your wide and butt out like a sumo wrestler child somewhere F 15 to 20 pushups against a wall, from your F Juggle or play with tossing a ball around from knees, or from your feet hand to hand (apples and oranges work great for this too!) F Park your car at the far end of the parking lot F When you take your kids to the playground, F Walk a “lap” or two of your workplace, your don’t stand there watching – join in for a few house, your apartment floor, the grocery moments! (They’ll love it.) store, etc.; or take the long way to get somewhere F Do one task while walking (e.g. -

Cybex Eagle® Overhead Press Owner's Manual Strength Systems

Cybex Eagle® Overhead Press Owner’s Manual Strength Systems Part Number 11010-999-4 A www.cybexinternational.com Cybex Eagle® Overhead Press Owner’s Manual Strength Systems Part Number 11010-999-4 A Cybex® and the Cybex logo are registered trademarks of Cybex International, Inc. Eagle® and its mark are registered trademarks of Cybex International, Inc. DISCLAIMER: Cybex International, Inc., makes no representations or warranties regarding the contents of this manual. We reserve the right to revise this document at any time or to make changes to the product described within it without notice or obligation to notify any person of such revisions or changes. © Copyright 2010, Cybex International, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. 10 Trotter Drive Medway, MA 02053 • 508-533-4300 • FAX 508-533-5183 www.cybexinternational.com • [email protected] • 11010-999-4 A Table of Contents 1 Safety Safety. 1-1 Safety Guidelines and Practices . 1-2 Warning/Caution Decals . 1-3 Regular Maintenance Activities . 1-5 Using Proper Form . 1-5 2 Exercises Intended Use . 2-1 Instructions. 2-1 3 Customer Service Contacting Service. 3-1 Ordering parts . 3-1 Return Material Authorization (RMA). 3-1 Damaged Parts . 3-2 4 Assembly Assembly . 4-1 5 Maintenance Daily Procedures . 5-1 Weekly Procedures . 5-4 Yearly Procedures . 5-6 Environment. 5-7 Storage . 5-7 Page i Cybex Eagle 11010 Overhead Press Owner’s Manual 1 - Safety Safety Read the Owner’s Manual carefully before assembling, servicing or using the equipment. It is the responsibility of the facility owner and/or owner of the equipment to instruct users on proper operation of the equipment and review all labels. -

Level 1 Training Guide Level 1 Training Guide

LEVEL 1 TRAINING GUIDE Level 1 Training Guide The CrossFit Level 1 Training Guide is a collection of CrossFit Journal articles written since 2002 primarily by CrossFit, Inc. Founder Coach Greg Glassman on the foun- dational movements and methodology of CrossFit, Inc. This guide is designed to be used in conjunction with the Level 1 Course to develop the participant’s knowledge and trainer skills and as an essential resource for any- one who is interested in improving their own health and fitness. Some edits to the original articles have been made for the Training Guide to flow as a stand-alone reference, to provide context for readers, and to stay current with the course format. All original works are preserved in the CrossFit Journal. © 2002–2020 CrossFit, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without permission. All images are copyrighted by the artists and reproduced with the kind permission of the artists and/or their representatives. Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders and to ensure that all the information presented is correct. Some of the facts in this volume may be subject to debate or dispute. If proper copyright acknowledgment has not been made, or for clarifications and corrections, please contact het publishers and we will correct the information in future reprintings, if any. No seminar other than the CrossFit Level 1 Certificate Course, as run by CrossFit, grants you the title CrossFit Trainer. Official events can only be verified by using CrossFit.com for registration or by emailing [email protected] with your inquiry.