Island Conservation Action in Northwest Mexico.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wild Edge 2 Thefreedom Towild Roam the Paciedgefic Coast a Photographic Journey by Florian Schulz

THE WILD EDGE 2 THEFREEDOM TOWILD ROAM THE PACIEDGEFIC COAST A PHOTOGRAPHIC JOURNEY BY FLORIAN SCHULZ INTRODUCTION BY BRUCE BARCOTT EPILOGUE BY PHILIPPE COUSTEAU 3 For Margot MacDougall— in loving memory of our friendship — F.S. C ONTENTS 9 11 14 PUBLISHER'S NoTE FoREWORD I NTRODUCTION A WILD IDEA CURRENTS OF LIFE T HE WILD PACIFIC EDGE H ELEN CHERULLO E XEQUIEL EZCURRA BRUCE BARCOTT 35 BAJA TO BEAUFORT A COASTAL JOURNEY ERIC SCIGLIANO P A R T O N E P A R T T W O P A R T T H R E E SOUTH CENTRAL NORTH 39 BAJA CALIFORNIA SUR, MEXICO, 91 NORTHERN CALIFORNIA TO PRINCE 157 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND, ALASKA, TO NORTHERN CALIFORNIA WILLIAM SOUND, ALASKA TO THE ARCTIC'S BEAUFORT SEA 223 225 EpL I OGUE C ITIZEN ScIENTIST CAUSE FOR HOPE CITIZEN SCIENCE TAKES OFF PHILIPPE COUSTEAU J ON HOEKSTRA MAPS 16 THE CORRIDOR FROM BAJA CALIFORNIA TO THE BEAUFORT SEA / 22 MARINE ECOREGIONS AND PRIORITY CONSERVATION AREAS / 40 SOUTH: BAJA CALIFORNIA SUR, MEXICO, TO NORTHERN CALIFORNIA / 92 CENTRAL: NORTHERN CALIFORNIA TO PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND, ALASKA / 158 NORTH: PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND, ALASKA, TO THE ARCTIC’s BEAUFORT SEA 226 WHERE TO SEE B2B WILDLIFE / 228 MIGRATION ROUTES OF GRAY WHALES AND SANDPIPERS 230 THE RooTS OF FREEDOM TO RoAM / 232 NoTES FROM THE FIELD / 234 ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS / 235 ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER / 236 AcKNOWLEDGMENTS / 238 INDEX Gray whale in the calving lagoons, where human access is strictly regulated by the Mexican government, Baja California Sur, Mexico PUBLISHER'S NoTE A WILD IDEA A Protected Wildlife Corridor from Mexico's Baja Peninsula to Alaska’s Beaufort Sea H ELEN CHERULLO ne of the stories from The Wild Edge that humans—thrive in place along abundant, healthy coastlines. -

The Geology of Isla Natividad, Baja California Sur, Mexico

The Geology of Isla Natividad, Baja California Sur, Mexico by Jon Sainsbury Abstract Isla Natividad is a Pacific island that sits just offshore to the west of Punta Eugenia on the Vizcaino Peninsula of Baja California. The geology of Baja California here preserves remnants of a Mesozoic Subduction zone-magmatic arc as well as Cenozoic rocks and structures that record the evolution of the region from a convergent margin to a strike slip dominated plate boundary. Isla Natividad is underlain almost entirely by sedimentary rocks of the Late Jurassic-Early Cretaceous Eugenia Formation which comprises part of the thick forearc basin marine stratigraphic assesmblages in the Vizcaino region. The type locality of the Eugenia Formation is at the fault bounded western tip of the Vizcaino Peninsula (Punta Eugenia), and it has also mapped on Cedros Island and recognized in reconnaissance on Isla Natividad. The goal of this study is to provide basic mapping and descriptions of the geology of Isla Natividad. Geologic mapping conducted in this study reveals that the main part of the island is dominated by gently southwest dipping strata that include conglomerate, turbidite and mudstone units. Conglomerate outcrops mainly on the NE coast of the island. It is dominated by cobble-boulder clast sizes that range from 0.1-0.5 meters. The maximum clast size observed is 0.75 meters. Conglomerates are clast-supported, massive, well-indurated and weathered to a dark grey color. Clast imbrication is locally present but there is no internal bedding or size grading. More than 50% of the clasts are rounded quartzite clasts. -

California Yellowtail Isla Natividad, Mexico

California Yellowtail Seriola lalandi (Seriola dorsalis) © Monterey Bay Aquarium Isla Natividad, Mexico Caught by Sociedad Cooperativa de Producción Pesquera Buzos y Pescadores de Baja California, S.C.L Handline February 24, 2014 Elizabeth Joubert, Consulting Researcher Disclaimer Seafood Watch® strives to ensure all our Seafood Reports and the recommendations contained therein are accurate and reflect the most up-to-date evidence available at time of publication. All our reports are peer- reviewed for accuracy and completeness by external scientists with expertise in ecology, fisheries science or aquaculture. Scientific review, however, does not constitute an endorsement of the Seafood Watch program or its recommendations on the part of the reviewing scientists. Seafood Watch is solely responsible for the conclusions reached in this report. We always welcome additional or updated data that can be used for the next revision. Seafood Watch and Seafood Reports are made possible through a grant from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. 2 Final Seafood Recommendation Stock / Fishery Impacts on Impacts on Management Habitat and Overall the Stock other Ecosystem Recommendation Species California yellowtail Green (3.32) Green (5.00) Yellow (3.00) Green (4.47) Best Choice (3.862) Baja Eastern Central Pacific - Handline Scoring note – Scores range from zero to five where zero indicates very poor performance and five indicates the fishing operations have no significant impact. Final Score = geometric mean of the four Scores (Criterion 1, Criterion 2, Criterion 3, Criterion 4). Best Choice = Final Score between 3.2 and 5, and no Red Criteria, and no Critical scores Good Alternative = Final score between 2.2 and 3.199, and Management is not Red, and no more than one Red Criterion other than Management, and no Critical scores Avoid = Final Score between 0 and 2.199, or Management is Red, or two or more Red Criteria, or one or more Critical scores. -

Plea to Cactus Explorers 44 Society Page 56 Travel with the Cactus Expert (1) 45 Retail Therapy 57 a Day in the Quebrada De Tastil 48 Echinomastus Johnsonii 52

TheCactus Explorer The first free on-line Journal for Cactus and Succulent Enthusiasts Succulents of Isla Cedros Sclerocactus polyancistrus Number 2 Echeveria laui in habitat ISSN 2048-0482 Echinomastus johnsonii November 2011 Matucana myriacantha The Cactus Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 2 November 2011 In thIs EdItIon Regular Features Articles Introduction 3 Succulents of Isla de Cedros 27 News and Events 4 My Trip with Arthur 2006 33 Recent New Descriptions 11 Echeveria laui is in Care 36 In the Glasshouse 17 Matucana myriacantha high above Journal Roundup 22 the Rio Crisnejas 40 The Love of Books 24 Plea to Cactus Explorers 44 Society Page 56 Travel with the Cactus Expert (1) 45 Retail Therapy 57 A Day in the Quebrada de Tastil 48 Echinomastus johnsonii 52 The No.1 source for on-line information about cacti and succulents is http://www.cactus-mall.com Cover Picture by Paul Klaassen Dudleya pachyphytum in habitat on Isla de Cedros, Baja California Sur, Mexico. See page 27 Invitation to Contributors Please consider the Cactus Explorer as the place to publish your articles. We welcome contributions for any of the regular features or a longer article with pictures on any aspect of cacti and succulents. The editorial team is happy to help you with preparing your work. Please send your submissions as plain text in a ‘Word’ document together with jpeg or tiff images with the maximun resolution available. A major advantage of this on-line format is the possibility of publishing contributions quickly and any issue is never full! We aim to publish your article within 3 months and the copy deadline is just a few days before the publication date which is planned for the 10th of February, May, August and November. -

Of Isla Cedros, Baja California, As Described in Father Miguel Venegas' 1739 Manuscript Obras Californianas

Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology | Vol. 26. Nn. 2 (2006) | pp. 123-152 THE HUAMALGUENOS OF ISLA CEDROS, BAJA CALIFORNIA, AS DESCRIBED IN FATHER MIGUEL VENEGAS' 1739 MANUSCRIPT OBRAS CALIFORNIANAS MATTHEW R. DES LAURIERS Department of Anthropology, California State University, Northridge CLAUDIA GARCIA-DES LAURIERS Department of Anthropology, Pomona College Father Miguel Venegas' 1739 Obras Californianas is the most extensive and detailed document covering the first forty years of the Jesuit period in Baja California. In addition to providing discussions of historical events, Venegas wrote extensively on the natural world and on indigenous cosmology, social networks, and lifeways. The section translated and annotated here includes the bulk of Venegas' writing on Isla Cedros and its native people. The island, located on the Pacific Coast of central Baja California, was home to a large, maritime-adapted indigenous society. The period of time (1728-1732) covered in this section of the much larger Venegas manuscript details the tragic end of Cedros Island's indigenous society, but preserves an account of their culture that is of inestimable value. The annotations included provide not only clarifications of meaning, but critical evaluations of the text and of the significance of particular passages within the larger context of Baja California indigenous and colonial history. HE JESUIT-AUTHORED DOCUMENTS touching Father Miguel Venegas (1680-1764) spent 64 years Tupon the history, indigenous cultures, and of his life as a Jesuit, although due to poor health, he environments of Baja California are well known for their was never able to pursue missionary activities in the detail and quality. -

Baja California, Costa Oeste

I N D I C E BAJA CALIFORNIA, COSTA OESTE Ø Banco Tanner – Isla Guadalupe Ø Monumento Línea Fronteriza – Cabo Colnett • Rosarito • Puerto Ensenada Ø Cabo Colnett – Punta Blanca • Puerto de San Quintin • Puerto Santa Catarina • Puerto de San José Ø Punta Blanca – Bahía Tortuga • Puerto Morro Redondo Ø Bahía Tortuga – Cabo San Lázaro • Puerto San Bartolomé • Archipiélago los Alijos. Ø Cabo San Lázaro – Cabo Falso • Puerto Magdalena • Puerto San Carlos • Puerto Cortes Ø Cabo Falso - Punta Arena de la Ventana Ø Punta Arena de la Ventana – Bahía San Gabriel COSTA OESTE DE LA PENINSULA DE BAJA CALIFORNIA DE BANCO TANNER A ISLA GUADALUPE La vegetación de la isla es muy árida en el S pero en la parte N es escasa en las montañas con algunos Banco Tanner (32° 42’ N, 119° 09’ W). Su valles fértiles. En la playa de una pequeña ensenada extremo NW se encuentra a 28 M hacia el SE del cercana al extremo NE de la isla hay un poco de agua extremo E de la Isla de San Nicolás, tiene alrededor de salobre, así como las ruinas de dos casas de color blanco, 12 M de largo en dirección WNW-ESE y 6 M de ancho, las cuales resultan bastante notables desde el mar. el banco se halla dentro de la curva de los 180 m, el bajo tiene una profundidad mínima de 21.9 m en su parte Dos pequeñas isletas rocosas se encuentran central, aunque se ha reportado otra de 16.5 m localizada cerca del extremo S de la isla. -

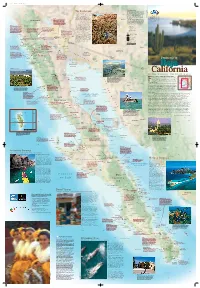

Baja California Map Guide

Baja map side 1/15/08 9:44 AM Page 1 S D N What is geotourism all about? N I A K L P S According to National Geographic, geotourism “sustains I O H A E N or enhances the geographical character of a place—its I The Borderland E L L A H environment, culture, aesthetics, heritage, and the well- T P A L C I N T E R M I N G L I N G F L A V O R S U N D E R G L O R I O U S L I G H T A A being of its residents.” Geotravelers, then, are people who R T 117° 116° 115° 112° N To live along the Baja California-U.S. like that idea, who enjoy authentic sense of place and A S care about maintaining it. They find that relaxing and N border is to be part of a shared history O T having fun gets better—provides a richer experence— E —Old West towns transformed into S geo.tour.ism (n): Tourism N when they get involved in the place and learn about U neon cities mixed with extreme cli- S that sustains or enhances the Mexicali mates and disparate cultures. You can what goes on there. geographical character of a Grab a seat at the El Acueducto bar in feel this sensation in Mexicali’s Chinese BPhoenix Geotravelers soak up local culture, hire local guides, place—its environment, culture, Hotel Lucerna and ask for the world restaurants where sweet and sour Asian buy local foods, protect the environment, and take pride aesthetics, heritage, and the CALIFORNIA famous tomato juice and clam juice in discovering and observing local customs. -

Of Isla Cedros, Baja California, As Described in Father Miguel Venegas' 1739 Manuscript Obras Californianas

UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Title The Huamalgüeños of Isla Cedros, Baja California, as Described in Father Miguel Venegas' 1739 Manuscript Obras Californianas Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9900444m Journal Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 26(2) ISSN 0191-3557 Authors Des Lauriers, Matthew R Des Lauriers, Claudia Garcia Publication Date 2006 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology | Vol. 26. Nn. 2 (2006) | pp. 123-152 THE HUAMALGUENOS OF ISLA CEDROS, BAJA CALIFORNIA, AS DESCRIBED IN FATHER MIGUEL VENEGAS' 1739 MANUSCRIPT OBRAS CALIFORNIANAS MATTHEW R. DES LAURIERS Department of Anthropology, California State University, Northridge CLAUDIA GARCIA-DES LAURIERS Department of Anthropology, Pomona College Father Miguel Venegas' 1739 Obras Californianas is the most extensive and detailed document covering the first forty years of the Jesuit period in Baja California. In addition to providing discussions of historical events, Venegas wrote extensively on the natural world and on indigenous cosmology, social networks, and lifeways. The section translated and annotated here includes the bulk of Venegas' writing on Isla Cedros and its native people. The island, located on the Pacific Coast of central Baja California, was home to a large, maritime-adapted indigenous society. The period of time (1728-1732) covered in this section of the much larger Venegas manuscript details the tragic end of Cedros Island's indigenous society, but preserves an account of their culture that is of inestimable value. The annotations included provide not only clarifications of meaning, but critical evaluations of the text and of the significance of particular passages within the larger context of Baja California indigenous and colonial history.