United States V. Miller, Mullet, Et

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Condition of England During the Wars of the Roses Author(S): Vincent B

Social Condition of England during the Wars of the Roses Author(s): Vincent B. Redstone Source: Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, New Series, Vol. 16 (1902), pp. 159-200 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Royal Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3678121 Accessed: 27-06-2016 09:27 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Royal Historical Society, Cambridge University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the Royal Historical Society This content downloaded from 198.91.37.2 on Mon, 27 Jun 2016 09:27:49 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms SOCIAL CONDITION OF ENGL ANI) DURING THE WARS OF THE ROSES. BY VINCENT B. REDSTONE Read Marsk 20, I902. THE social life of the inhabitants of England during the Introduc years of strife which brought about the destruction of the t on- feudal nobility, gave to the middle class a new position in the State, and freed the serf from the shackles of bondage, has been for some time past a subject of peculiar interest to the student of English history. -

Surnames in Bureau of Catholic Indian

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Montana (MT): Boxes 13-19 (4,928 entries from 11 of 11 schools) New Mexico (NM): Boxes 19-22 (1,603 entries from 6 of 8 schools) North Dakota (ND): Boxes 22-23 (521 entries from 4 of 4 schools) Oklahoma (OK): Boxes 23-26 (3,061 entries from 19 of 20 schools) Oregon (OR): Box 26 (90 entries from 2 of - schools) South Dakota (SD): Boxes 26-29 (2,917 entries from Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records 4 of 4 schools) Series 2-1 School Records Washington (WA): Boxes 30-31 (1,251 entries from 5 of - schools) SURNAME MASTER INDEX Wisconsin (WI): Boxes 31-37 (2,365 entries from 8 Over 25,000 surname entries from the BCIM series 2-1 school of 8 schools) attendance records in 15 states, 1890s-1970s Wyoming (WY): Boxes 37-38 (361 entries from 1 of Last updated April 1, 2015 1 school) INTRODUCTION|A|B|C|D|E|F|G|H|I|J|K|L|M|N|O|P|Q|R|S|T|U| Tribes/ Ethnic Groups V|W|X|Y|Z Library of Congress subject headings supplemented by terms from Ethnologue (an online global language database) plus “Unidentified” and “Non-Native.” INTRODUCTION This alphabetized list of surnames includes all Achomawi (5 entries); used for = Pitt River; related spelling vartiations, the tribes/ethnicities noted, the states broad term also used = California where the schools were located, and box numbers of the Acoma (16 entries); related broad term also used = original records. Each entry provides a distinct surname Pueblo variation with one associated tribe/ethnicity, state, and box Apache (464 entries) number, which is repeated as needed for surname Arapaho (281 entries); used for = Arapahoe combinations with multiple spelling variations, ethnic Arikara (18 entries) associations and/or box numbers. -

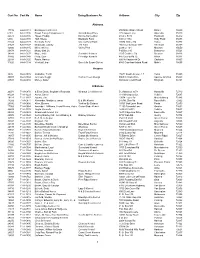

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 17732 64-A-0118 Barking Acres Kennel 250 Naftel Ramer Road Ramer 36069 6181 64-A-0136 Brown Family Enterprises Llc Grandbabies Place 125 Aspen Lane Odenville 35120 22373 64-A-0146 Hayes, Freddy Kanine Konnection 6160 C R 19 Piedmont 36272 6394 64-A-0138 Huff, Shelia Blackjack Farm 630 Cr 1754 Holly Pond 35083 22343 64-A-0128 Kennedy, Terry Creeks Bend Farm 29874 Mckee Rd Toney 35773 21527 64-A-0127 Mcdonald, Johnny J M Farm 166 County Road 1073 Vinemont 35179 42800 64-A-0145 Miller, Shirley Valley Pets 2338 Cr 164 Moulton 35650 20878 64-A-0121 Mossy Oak Llc P O Box 310 Bessemer 35021 34248 64-A-0137 Moye, Anita Sunshine Kennels 1515 Crabtree Rd Brewton 36426 37802 64-A-0140 Portz, Stan Pineridge Kennels 445 County Rd 72 Ariton 36311 22398 64-A-0125 Rawls, Harvey 600 Hollingsworth Dr Gadsden 35905 31826 64-A-0134 Verstuyft, Inge Sweet As Sugar Gliders 4580 Copeland Island Road Mobile 36695 Arizona 3826 86-A-0076 Al-Saihati, Terrill 15672 South Avenue 1 E Yuma 85365 36807 86-A-0082 Johnson, Peggi Cactus Creek Design 5065 N. Main Drive Apache Junction 85220 23591 86-A-0080 Morley, Arden 860 Quail Crest Road Kingman 86401 Arkansas 20074 71-A-0870 & Ellen Davis, Stephanie Reynolds Wharton Creek Kennel 512 Madison 3373 Huntsville 72740 43224 71-A-1229 Aaron, Cheryl 118 Windspeak Ln. Yellville 72687 19128 71-A-1187 Adams, Jim 13034 Laure Rd Mountainburg 72946 14282 71-A-0871 Alexander, Marilyn & James B & M's Kennel 245 Mt. -

Ipsos MORI: Men's Grooming and the Beard of Time

MEN’S GROOMING IN NUMBERS Men spend 8 days 57% a year on grooming themselves Men currently have 5 personal care of men don’t style their hair at all products on their bathroom shelf, on average 26% of men shave their face Of those men every day, 19% once a week 18% who have used a women’s razor, or less and 10% do not ever of men have used 20% said they did it because the women’s shave their face a women’s razor product was more effective (but most did it because of availability/convenience) Most commonly men 53% 20% spend 4-5 minutes (23%) of men don’t of men 74% of men have used shaving moisturise their moisturise each time they shave foam/gels, 29% face scrubs, 81% face at all their face daily razors Source: Ipsos MORI, fieldwork was conducted online between 29 July and 2 August 2016, with 1,119 GB adults aged 16-75. HAIR AND FACIAL TRENDS THROUGH THE BEARD OF TIME 3000bc 400bc Ancient Egyptians Greeks perceived the beard were always clean shaved. as a sign of high status & False beards were worn as wisdom. Men grew, groomed a sign of piety and after death. and styled their beards to imitate the Gods Zeus and Hercules. 340bc Alexander the Great encouraged his soldiers to shave their beards 1 AD – 300 AD before battle to avoid the enemies Both Greeks and Romans started pulling them off their horses. shaving their beards claiming they’re “a creator of lice and not of brains”. -

2021Newitem Cat8 Digital3 P1-P10.Indd

COSTUME CULTURE Catalog No. 78 2021 New Collection 29412 Leopard Kit Velour (Min. 12 pcs.) 31924 Leopard Gloves Velour (Min. 12 pcs.) 31927 21126 Tiger Gloves Tiger Mullet Wig & Moustache Blonde Velour (Min. 12 pcs.) 2 855.399.2250 ANIMAL PRINTS 29413 Tiger Kit Velour (Min. 12 pcs.) 48565 Leopard Jumpsuit Spandex Jumpsuit w/Attached Tail Headband & Gloves Small, Medium & Large 21129 Cool Cat Wig Blonde costumeculture.com 3 49882 48668 Evil Doll Mens Evil Doll Ladies Overalls & Attached Shirt Overall Dress & Thigh Highs Standard & Extra Large Small, Medium & Large Wig Sold Separately 21117 Wig Sold Separately 21131 4 855.399.2250 EVIL DOLL COLLECTION EVIL DOLL COLLECTION 49880 49916 Evil Doll Girl Evil Doll Child Overall Dress & Knee Highs Overalls & Attached Shirt Small, Medium & Large S/M, M/L & L/XL Wig Sold Separately 21118 costumeculture.com 5 48696 Super Seventies 32380-08 Rock You Cape Jumpsuit & Belt Unisex Cape Small, Medium & Large One Size Fits Most Wig Sold Separately 21130 6 855.399.2250 COSTUMES 49814 Medieval Knight 49813 Lazy Guy Vest w/Attached Belt, Shoulder Robe w/Attached Belt & Arm Guards, Arm Cu s & Boot Tops Wig & Goatee Standard & Extra Large One Size Fits Most Wig Sold Separately 24981-15 7 21132-01 21132-11 21132-30 Long Bob Black Long Bob Blonde Long Bob Iridescent 24984 24987 24981-15 Deluxe Lazy Guy Wig & Goatee Brown Willie Mixed Grey Medieval Knight Grey (Bandana not included) 24975 24986 21127 Candidate White Veep Brown Feisty Fauci Grey 8 855.399.2250 WIGS Michele’s Wig Collection Michele’s 24985-07 21072-12 24983-11 Ciao Bella Natural Red Coolness Brown Milkmaid Braid Blonde Heat Resistant Wigs Curling/Flat Iron Safe Up to 350°F/180°C 21131 Evil Doll Ladies Red 21130 26000 26001 Super Seventies Neon Orange Deluxe Pink Berry Pink Deluxe Chocolate Berry Brown costumeculture.com 9 ACCESSORIES 28138-13 28138-14 Ancient Crown PBH Ancient Crown PBH Pewter (Min. -

Dalton Fire Department S.0.G.: Gp-3

DALTON FIRE DEPARTMENT Standard Operating Guideline S.0.G.: GP-3 Effective: 08/27/2019 Revised: ______________________________ __________ Reviewed: 08/24/2021 Fire Chief Signature DATE Division: All Subject: Professional Grooming Purpose: To establish a guideline detailing professional grooming and uniform standards that contribute to uniformity of appearance, professionalism, esprit de corps and firefighter safety. Scope: All personnel PROCEDURE: Personnel present an image of competence, efficiency and pride. It is critical to the operations that members are groomed in such a manner to instill confidence in the public. Personnel shall maintain their appearance in a manner consistent with professionalism in the fire service and in keeping with applicable safety and accident prevention standards in the workplace. All individuals shall be clean, neat and well-groomed in consideration of the extremely close personal contact required between personnel and our citizens. All employees of the department are subject to the provisions of this Standard Operating Guideline, and must adhere to the content within this document. Unless it is specifically addressed, the Fire Chief will be the final authority of items not covered under this guideline. Hair Standards for Suppression Personnel 1. The department recognizes that traditionally acceptable standards for female firefighter hairstyles, and length, may differ considerably from those of male firefighters. Female hairstyles that would normally not conform to the standards outlined in this policy may be pinned up or secured in order to comply while on duty, and shall not interfere with proper wearing of uniform hats or protective equipment, or in any way create a safety hazard. 2. Hair accessories such as clips, rubber bands, pins, combs, or barrettes, must be transparent or similar in color to the individual’s hair color and shall be concealed as much as possible. -

List of Hairstyles

List of hairstyles This is a non-exhaustive list of hairstyles, excluding facial hairstyles. Name Image Description A style of natural African hair that has been grown out without any straightening or ironing, and combed regularly with specialafro picks. In recent Afro history, the hairstyle was popular through the late 1960s and 1970s in the United States of America. Though today many people prefer to wear weave. A haircut where the hair is longer on one side. In the 1980s and 1990s, Asymmetric asymmetric was a popular staple of Black hip hop fashion, among women and cut men. Backcombing or teasing with hairspray to style hair on top of the head so that Beehive the size and shape is suggestive of a beehive, hence the name. Bangs (or fringe) straight across the high forehead, or cut at a slight U- Bangs shape.[1] Any hairstyle with large volume, though this is generally a description given to hair with a straight texture that is blown out or "teased" into a large size. The Big hair increased volume is often maintained with the use of hairspray or other styling products that offer hold. A long hairstyle for women that is used with rich products and blown dry from Blowout the roots to the ends. Popularized by individuals such asCatherine, Duchess of Cambridge. A classic short hairstyle where it is cut above the shoulders in a blunt cut with Bob cut typically no layers. This style is most common among women. Bouffant A style characterized by smooth hair that is heightened and given extra fullness over teasing in the fringe area. -

Rethinking the US History Survey Steven Mintz University of Texas at Austin 2018 AHA Texas Conference on Introductory History Courses

Rethinking the US History Survey Steven Mintz University of Texas at Austin 2018 AHA Texas Conference on Introductory History Courses Multi-Tiered Assessment Strategies Checks for understanding ▪ Informational questions that call for factual information. ▪ Diagnostic questions to determine what students know and don’t yet grasp. ▪ Provocations, questions that pose a challenge, for example, by asking students how they might explain a phenomenon or why they have reached a particular conclusion or how they would convince someone of a particular position. ▪ Role-playing questions that ask what one might do in a particular context or position. ▪ Summary questions that call on students to recapitulate or encapsulate an idea or argument. ▪ Generalization questions that seek to identify broad conclusions that might be drawn from a case study or an experiment. Short Essay Prompts that ask students to ▪ Debunk historical myths ▪ Address a what if question ▪ Refute an argument ▪ Render a historical judgment ▪ Evaluate and analyze a piece of evidence ▪ Connect past to present New Ways to Organize, Visualize, Analyze, and Present Data ▪ Ngrams ▪ Infographics ▪ Knowledge and concept mapping ▪ Geovisualization ▪ Event and causal factor charting Project-Based Assessment Digital story, infographic, oral history or interview, policy brief, podcast Team-Based Assessment Annotated text, collaborative website, virtual encyclopedia, visual or audio tour, virtual museum Valuable Websites, Apps, Simulations, and Visualizations for History Teaching American Panorama -

Characterizing the Stream Environments Associated with Introduced Species Across Spatial Scales in Hawai‘I

CHARACTERIZING THE STREAM ENVIRONMENTS ASSOCIATED WITH INTRODUCED SPECIES ACROSS SPATIAL SCALES IN HAWAI‘I A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT DECEMBER 2018 By Brendan T. Martin Thesis Committee: Yin-Phan Tsang, Chairperson Melissa Price Tim Grabowski Keywords: Hawai‘i, stream, freshwater, tropical, introduced, alien, modeling, landscape Copyright by Brendan T. Martin 2018 ii Acknowledgements I would like to extend my gratitude to my committee chair, Yin-Phan Tsang, for her guidance and friendship throughout my research. I would also like to thank my committee members, Tim Grabowski and Melissa Price, for their support and invaluable comments and suggestions that enabled me to complete this thesis. I thank my lab family, Hannah Clilverd, Yu-Fen Huang, and Kelly-rose Lariosa for their critiques and support during the many phases of my research. I am extremely grateful to Glenn Higashi of Hawaii’s Division of Aquatic Resources who provided the biological survey data which made my research possible. Additionally, I would like to thank Ralph Tingley, Dana Infante, and Kyle Herreman for assisting with acquisition and assessment of landscape data sources. I would like to thank many colleagues that contributed their expert knowledge on Hawaiian streams to the development of research including Cory Yap, Ayron Strauch, Malie Beach- Smith, Abigail Lynch, Dan Polhemus, Kauaoa Fraiola, and Gordon Smith. Finally, I am thankful for my family who has always supported my endeavors, and my wife for being my biggest supporter along the way. -

Grooming and Appearance in Uniform

COLORADO WING ENCAMPMENT HEADQUARTERS CIVIL AIR PATROL UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AUXILIARY 19210 East Breckenridge Avenue, Stop 33 Buckley AFB CO 80011-9525 Grooming and Appearance in Uniform CAP Manual 39-1, CAP Uniform Manual, requires all senior members wearing AF style uniforms and all cadets to comply with all dress and appearance requirements as described in the referenced manual. CAP Manual 39-1, Paragraph 1.1.1.4. It is critical for members to maintain a high standard of dress and personal appearance. The five elements of this standard are neatness, cleanliness, safety, uniformity, and good organizational image. The first four are absolute, objective criteria needed for the efficiency and well-being of the CAP. The fifth criterion, good organizational image, is subjective but necessary. Appearance in uniform is an important part of CAP’s corporate image. Judgment on what is the proper image may differ. The American public and its elected representatives draw certain conclusions on military effectiveness based on the image CAP members present. The image must instill public confidence and leave no doubt that CAP members adhere to our Core Values and are effective and professional in executing our missions. The image of a professional and committed CAP member is incompatible with the extreme, the unusual, and the fad. CAP Manual 39-1, Chapter 3. Personal Grooming Standards. This chapter of the manual is available on the CAP NHQ Website and the Encampment Website Home Page. Each encampment participant must review this chapter prior to encampment to ensure compliance with CAP appearance and grooming standards. Chapter 3 of Uniform Manual covers the specific requirements for the following when wearing USAF Style Uniforms and CAP Corporate uniforms. -

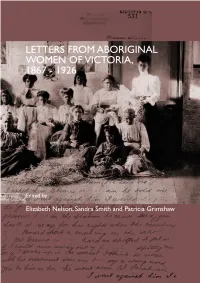

Letters from Aboriginal Women of Victoria, 1867-1926, Edited by Elizabeth Nelson, Sandra Smith and Patricia Grimshaw (2002)

LETTERS FROM ABORIGINAL WOMEN OF VICTORIA, 1867 - 1926 LETTERS FROM ABORIGINAL WOMEN OF VICTORIA, 1867 - 1926 Edited by Elizabeth Nelson, Sandra Smith and Patricia Grimshaw History Department The University of Melbourne 2002 © 2002 Copyright is held on individual letters by the individual contributors or their descendants. No reproduction without permission. All rights reserved. Published in 2002 by The History Department The University of Melbourne Melbourne, Australia The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Letters from aboriginal women in Victoria, 1867-1926. ISBN 0 7340 2160 7. 1. Aborigines, Australian - Women - Victoria - Correspondence. 2. Aborigines, Australian - Women - Victoria - Social conditions. 3. Aborigines, Australian - Government policy - Victoria. 4. Victoria - History. I. Grimshaw, Patricia, 1938- . II. Nelson, Elizabeth, 1972- . III. Smith, Sandra, 1945- . IV. University of Melbourne. Dept. of History. (Series : University of Melbourne history research series ; 11). 305.8991509945 Front cover details: ‘Raffia workers at Coranderrk’ Museum of Victoria Photographic Collection Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria Layout and cover design by Design Space TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 7 Map 9 Introduction 11 Notes on Editors 21 The Letters: Children and family 25 Land and housing 123 Asserting personal freedom 145 Regarding missionaries and station managers 193 Religion 229 Sustenance and material assistance 239 Biographical details of the letter writers 315 Endnotes 331 Publications 357 Letters from Aboriginal Women of Victoria, 1867 - 1926 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We have been helped to pursue this project by many people to whom we express gratitude. Patricia Grimshaw acknowledges the University of Melbourne Small ARC Grant for the year 2000 which enabled transcripts of the letters to be made. -

Hair-Guide-Ebook.Pdf

h The Ultimate Guide To MEN’S HAIR Presented by Real Men Real Style REAL MEN REAL STYLE THE ULTIMATE GUIDE TO MEN’S HAIR Copyright, Legal Notice and Disclaimer This publication is protected under the US Copyright Act of 1976 and all other applicable international, federal, state and local laws, and all rights are reserved, including resale rights: you are not allowed to give or sell this Guide to anyone else. Please note that much of this publication is based on personal experience and anecdotal evidence. Although the author and publisher have made every reasonable attempt to achieve complete accuracy of the content in this Guide, they assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. Also, you should use this information as you see fit, and at your own risk. Your particular situation may not be exactly suited to the examples illustrated here; in fact, it's likely that they won't be the same, and you should adjust your use of the information and recommendations accordingly. Any trademarks, service marks, product names or named features are assumed to be the property of their respective owners, and are used only for reference. There is no implied endorsement if we use one of these terms. Finally, use your head. Nothing in this Guide is intended to replace common sense, legal, medical or other professional advice, and is meant to inform and entertain the reader. So have fun and learn to dress sharp! Page 1 - click here to go back to Table Of Contents eBook Title - Copyright 2020 | Real Men Real Style REAL MEN REAL STYLE THE ULTIMATE GUIDE TO MEN’S HAIR Contents Chapter 1: The Basic Elements 4 Chapter 2: The Attitude 12 Consistent Vs.