Serial Murder As Allegory: a Subconscious Echo Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Death Row U.S.A

DEATH ROW U.S.A. Summer 2017 A quarterly report by the Criminal Justice Project of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Deborah Fins, Esq. Consultant to the Criminal Justice Project NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Death Row U.S.A. Summer 2017 (As of July 1, 2017) TOTAL NUMBER OF DEATH ROW INMATES KNOWN TO LDF: 2,817 Race of Defendant: White 1,196 (42.46%) Black 1,168 (41.46%) Latino/Latina 373 (13.24%) Native American 26 (0.92%) Asian 53 (1.88%) Unknown at this issue 1 (0.04%) Gender: Male 2,764 (98.12%) Female 53 (1.88%) JURISDICTIONS WITH CURRENT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 33 Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington, Wyoming, U.S. Government, U.S. Military. JURISDICTIONS WITHOUT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 20 Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico [see note below], New York, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin. [NOTE: New Mexico repealed the death penalty prospectively. The men already sentenced remain under sentence of death.] Death Row U.S.A. Page 1 In the United States Supreme Court Update to Spring 2017 Issue of Significant Criminal, Habeas, & Other Pending Cases for Cases to Be Decided in October Term 2016 or 2017 1. CASES RAISING CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTIONS First Amendment Packingham v. North Carolina, No. 15-1194 (Use of websites by sex offender) (decision below 777 S.E.2d 738 (N.C. -

Mob Storms Into Tehran As Oil Halts

PAGE TWENTY-EIGHT - MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD. Manchester, Conn.. Wed.. Dec. 27. I97B other information could you Now. I’m not sure what colic sometimes benefit cage near the gallbladder give me about treatment of kind of X ray you had for from a low-fat diet. Fat region may be confused with the colic? your gallbladder, but some stimulates the gallbladder to discomfort from gallbladder What’s up In auto theft? DEAR READER - It is stones show up on an X ray contract, resulting in colic. disease. unlikely that your pain is and other don’t, depending This is not true of either pure' When such patients have Think twice about parking your car on a Boston street. HEALTH caused by gallbladder colic. upon their chemical compo protein or carbohydrates. their gallbladder removed, According to a recent survey by a'leading Insurance V^y? Because you don’t sition. I am sending you The often they don’t get relief company, Beantown has the highest auto thelt rate In the 1 " Lawrence E.Lamb.M.D. have any gallstones. Most The ones that don’t have to Health Letter number 4-9, from their symptoms be nation. attacks of gallbladder colic be visualized by X ray after Gall Stones and Gall cause the pain wasn't Here are the auto theft rates per 100.000 people as well Senator*s Win Costly 1 East Catholic Boysj Girls 1 Body Count Now 17 1 Guyana Top Headliner are caused by sudden ob taking a gallbladder dye. Bladder Disease. It will give caused by the gallbladder to as the costs ol a comprehensive theft policy on a struction of the bile duct — T his^ usi^ally done by giv you more information on begin with. -

The John Wayne Gacy Murders Pdf Free Download

KILLER CLOWN: THE JOHN WAYNE GACY MURDERS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Terry Sullivan,Professor Peter T Maiken | 419 pages | 01 May 2013 | Kensington Publishing | 9780786032549 | English | New York, United States Killer Clown: The John Wayne Gacy Murders by Terry Sullivan Armed with the signed search warrant, police and evidence technicians drove to Gacy's home. On their arrival, officers found Gacy had unplugged his sump pump , flooding the crawl space with water; to clear it, they simply replaced the plug and waited for the water to drain. After it had done so, evidence technician Daniel Genty entered the byfoot 8. Genty immediately shouted to the investigators that they could charge Gacy with murder, adding, "I think this place is full of kids". A police photographer then dug in the northeast corner of the crawl space, uncovering a patella. The two then began digging in the southeast corner, uncovering two lower leg bones. The victims were too decomposed to be Piest. As the body discovered in the northeast corner was later unearthed, a crime scene technician discovered the skull of a second victim alongside this body. Later excavations of the feet of this second victim revealed a further skull beneath the body. After being informed that the police had found human remains in his crawl space and that he would now face murder charges, Gacy told officers he wanted to "clear the air", adding he had known his arrest was inevitable since the previous evening, which he had spent on the couch in his lawyers' office. In the early morning hours of December 22, and in the presence of his lawyers, Gacy provided a formal statement in which he confessed to murdering approximately 30 young males—all of whom he claimed had entered his house willingly. -

X********X************************************************** * Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made * from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 302 264 IR 052 601 AUTHOR Buckingham, Betty Jo, Ed. TITLE Iowa and Some Iowans. A Bibliography for Schools and Libraries. Third Edition. INSTITUTION Iowa State Dept. of Education, Des Moines. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 312p.; Fcr a supplement to the second edition, see ED 227 842. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibllographies; *Authors; Books; Directories; Elementary Secondary Education; Fiction; History Instruction; Learning Resources Centers; *Local Color Writing; *Local History; Media Specialists; Nonfiction; School Libraries; *State History; United States History; United States Literature IDENTIFIERS *Iowa ABSTRACT Prepared primarily by the Iowa State Department of Education, this annotated bibliography of materials by Iowans or about Iowans is a revised tAird edition of the original 1969 publication. It both combines and expands the scope of the two major sections of previous editions, i.e., Iowan listory and literature, and out-of-print materials are included if judged to be of sufficient interest. Nonfiction materials are listed by Dewey subject classification and fiction in alphabetical order by author/artist. Biographies and autobiographies are entered under the subject of the work or in the 920s. Each entry includes the author(s), title, bibliographic information, interest and reading levels, cataloging information, and an annotation. Author, title, and subject indexes are provided, as well as a list of the people indicated in the bibliography who were born or have resided in Iowa or who were or are considered to be Iowan authors, musicians, artists, or other Iowan creators. Directories of periodicals and annuals, selected sources of Iowa government documents of general interest, and publishers and producers are also provided. -

Frequencies Between Serial Killer Typology And

FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS A dissertation presented to the faculty of ANTIOCH UNIVERSITY SANTA BARBARA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY in CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY By Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori March 2016 FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS This dissertation, by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: _______________________________ Ron Pilato, Psy.D. Chairperson _______________________________ Brett Kia-Keating, Ed.D. Second Faculty _______________________________ Maxann Shwartz, Ph.D. External Expert ii © Copyright by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, 2016 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS LERYN ROSE-DOGGETT MESSORI Antioch University Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA This study examined the association between serial killer typologies and previously proposed etiological factors within serial killer case histories. Stratified sampling based on race and gender was used to identify thirty-six serial killers for this study. The percentage of serial killers within each race and gender category included in the study was taken from current serial killer demographic statistics between 1950 and 2010. Detailed data -

Desiring Dexter: the Pangs and Pleasures of Serial Killer Body Technique

Desiring Dexter: The pangs and pleasures of serial killer body technique Author Green, Stephanie Published 2012 Journal Title Continuum DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2012.698037 Copyright Statement © 2012 Taylor & Francis. This is an electronic version of an article published in Continuum, Volume 26, Issue 4, 2012, Pages 579-588. Continuum is available online at: http:// www.tandfonline.com with the open URL of your article. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/48836 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Desiring Dexter: the pangs and pleasures of serial killer body technique Stephanie Green1 School of Humanities, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia Abstract The television series Dexter uses the figure of appealing monstrosity to unfold troubled relationships between corporeality, spectatorship and desire. Through a plastic-wrapped display of body horror, lightly veiled by suburban romance, Dexter turns its audience on to the consuming sensations of blood, death and dismemberment while simultaneously alluding to its own narrative and ethical contradictions. The excitations of Dexter are thus encapsulated within a tension between form and content as ambivalent and eroticised desire; both for heroic transgression and narrative resolution. Arguably, however, it is Dexter’s execution of a carefully developed serial killer body technique which makes this series so compelling. Through an examination of Dexter and his plotted body moves, this paper explores the representations of intimacy and murderous identity in this contemporary example of domestic screen horror entertainment. Keywords: Dexter, body-technique, desire, crime television, horror 1 [email protected] Launched in 2006, the television drama series Dexter has been a ratings record- breaker for its network producers (Showtime, CBS 2007-2011). -

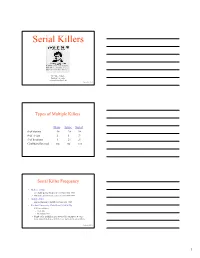

Serial Killers

Serial Killers Dr. Mike Aamodt Radford University [email protected] Updated 01/24/2010 Types of Multiple Killers Mass Spree Serial # of victims 4+ 2+ 3+ # of events 1 1 3+ # of locations 1 2+ 3+ Cooling-off period no no yes Serial Killer Frequency • Hickey (2002) – 337 males and 62 females in U.S. from 1800-1995 – 158 males and 29 females in U.S. from 1975-1995 • Gorby (2000) – 300 international serial killers from 1800-1995 • Radford University Data Base (1/24/2010) – 1,961 serial killers • US: 1,140 • International: 821 – Number of serial killers goes down with each update because many names listed as serial killers are not actually serial killers Updated 01/24/2010 1 General Serial Killer Profile Demographics - Worldwide • Male – Our data base: 88.27% – Kraemer, Lord & Heilbrun (2004) study of 157 serial killers: 96% • White – 66.5% of all serial killers (68% in Kraemer et al, 2004) – 64.3% of male serial killers – 83% of female serial killers • Average intelligence – Mean of 101 in our data base (median = 100) –n = 107 • Seldom involved with groups Updated 01/24/2010 General Serial Killer Profile Age at First Kill Race N Mean Our data (2010) 1,518 29.0 Kraemer et al. (2004) 157 31 Hickey (2002) 28.5 Updated 01/24/2010 General Serial Killer Profile Demographics – Average age is 29.0 • Males – 28.8 is average age at first kill • 9 is the youngest (Robert Dale Segee) • 72 is the oldest (Ray Copeland) – Jesse Pomeroy (Boston in the 1870s) • Killed 2 people and tortured 8 by the age of 14 • Spent 58 years in solitary confinement until he died • Females – 30.3 is average age at first kill • 11 is youngest (Mary Flora Bell) • 66 is oldest (Faye Copeland) Updated 01/24/2010 2 General Serial Killer Profile Race Race U.S. -

Ethics Questions Raised by the Neuropsychiatric

REGULAR ARTICLE Ethics Questions Raised by the Neuropsychiatric, Neuropsychological, Educational, Developmental, and Family Characteristics of 18 Juveniles Awaiting Execution in Texas Dorothy Otnow Lewis, MD, Catherine A. Yeager, MA, Pamela Blake, MD, Barbara Bard, PhD, and Maren Strenziok, MS Eighteen males condemned to death in Texas for homicides committed prior to the defendants’ 18th birthdays received systematic psychiatric, neurologic, neuropsychological, and educational assessments, and all available medical, psychological, educational, social, and family data were reviewed. Six subjects began life with potentially compromised central nervous system (CNS) function (e.g., prematurity, respiratory distress syndrome). All but one experienced serious head traumas in childhood and adolescence. All subjects evaluated neurologically and neuropsychologically had signs of prefrontal cortical dysfunction. Neuropsychological testing was more sensitive to executive dysfunction than neurologic examination. Fifteen (83%) had signs, symptoms, and histories consistent with bipolar spectrum, schizoaffective spectrum, or hypomanic disorders. Two subjects were intellectually limited, and one suffered from parasomnias and dissociation. All but one came from extremely violent and/or abusive families in which mental illness was prevalent in multiple generations. Implications regarding the ethics involved in matters of culpability and mitigation are considered. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 32:408–29, 2004 The first well-documented case in America of execut- principle, the New Jersey Supreme Court, in the case ing a child antedates the American Revolution. In of State v. Aaron,5 overturned the death sentence of 1642, a 16-year-old boy, Thomas Graunger, was an 11-year-old slave convicted of murdering a hanged for the crime of bestiality, having sodomized younger child. -

The Birth Pangs of Creation: the Eschatological Transformation of Nature in Romans 8:19-22

The Birth Pangs of Creation: The Eschatological Transformation of Nature in Romans 8:19-22 by Dr. Harry Alan Hahne Professor of New Testament, Gateway Seminary Presented at the Evangelical Theological Society Annual Meeting, November 15, 2017 Romans 8:19-22 discusses the present suffering of the natural world due to the human Fall. Although the natural world is not itself fallen or disobedient to God, Adam’s sin brought the created order into bondage to death, decay, corruption and futility. Yet Paul describes this suffering in the context of great eschatological hope both for believers and the natural world: The suffering of creation is like birth pangs leading to a glorious new world, rather than the death pangs of a dying creation.1 The redemption that Christ brings will have cosmic consequences: At the second coming of Christ the natural order will be restored to its proper operation, so that it may fulfill the purpose for which it was created. This passage focuses on two major themes: (1) the present corruption of the subhuman creation as a result of the Fall of Adam, which results in a futile cycle of decay and death; and (2) the eschatological redemption of creation which will deliver it from corruption and transform it into a state of freedom and glory. Paul uses the two-sided metaphor of birth pangs to embrace both of these themes: As a metaphor of intense suffering it symbolizes the present suffering of creation. As a metaphor of productive pain that brings a positive outcome, it points to the eschatological hope of the redemption of creation. -

Comparative Evaluation of the Concept of “Repetition Compulsion” from a Psychoanalytic and a Neurophysiological Perspective

89 Comparative Evaluation of the Concept of “Repetition Compulsion” from a Psychoanalytic and a Neurophysiological perspective George Skalkotοs2 Abstract The term repetition compulsion was first used by Freud in 1914 in his work “Remembering, Repeating and Working-Through”. Ever since, it has been connected with many situations in the psychoanalytic theory, which are sometimes contradictory to one another, sometimes conscious or unconscious, traumatic or therapeutic. In the first part of the present article we attempt to review the phenomenon of repetition compulsion in Freud’s, as well as in other scholars’ writings. The concept of repetition, of the act, that is, and of the outcome of “repeating” can be found in many fields. In the field of Neurosciences, research presents repetition processes in conjunction with memory function, which for some, like Modell, constitutes a kind of neurobiological support of Freud’s work. In the second part of the article we attempt to underline the points where Neurosciences and Psychoanalysis meet. Key-words: repetition compulsion, trauma, pleasure principle, transference, countertransference, death drive, memory, deferred action, pattern completion Psychoanalysis, Neurophysiology ON THEM Night came again like yesterday. Like yesterday night came again. Night came. Yesterday. Again. Effort in vain to strike the meaning, the solidarity of woe. Relentlessly, with whichever metathesis of words, 2 Social worker, psychotherapist – Mental Health Centre U.M.H.R.I. ([email protected]). The present essay was written for the “Psychodynamic Psychotherapy and Neurosciences” module of the Postgraduate Course “Psychodynamic Psychotherapy in Medical Settings” of the School of Medicine of the University of Athens. 90 with whichever release. -

Buffy at Play: Tricksters, Deconstruction, and Chaos

BUFFY AT PLAY: TRICKSTERS, DECONSTRUCTION, AND CHAOS AT WORK IN THE WHEDONVERSE by Brita Marie Graham A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSTIY Bozeman, Montana April 2007 © COPYRIGHT by Brita Marie Graham 2007 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL Of a thesis submitted by Brita Marie Graham This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Dr. Linda Karell, Committee Chair Approved for the Department of English Dr. Linda Karell, Department Head Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Carl A. Fox, Vice Provost iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it availably to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Brita Marie Graham April 2007 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In gratitude, I wish to acknowledge all of the exceptional faculty members of Montana State University’s English Department, who encouraged me along the way and promoted my desire to pursue a graduate degree. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74