Glider Handbook, Chapter 4: Flight Instruments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pitot-Static System Blockage Effects on Airspeed Indicator

The Dramatic Effects of Pitot-Static System Blockages and Failures by Luiz Roberto Monteiro de Oliveira . Table of Contents I ‐ Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….1 II ‐ Pitot‐Static Instruments…………………………………………………………………………………………..3 III ‐ Blockage Scenarios – Description……………………………..…………………………………….…..…11 IV ‐ Examples of the Blockage Scenarios…………………..……………………………………………….…15 V ‐ Disclaimer………………………………………………………………………………………………………………50 VI ‐ References…………………………………………………………………………………………….…..……..……51 Please also review and understand the disclaimer found at the end of the article before applying the information contained herein. I - Introduction This article takes a comprehensive look into Pitot-static system blockages and failures. These typically affect the airspeed indicator (ASI), vertical speed indicator (VSI) and altimeter. They can also affect the autopilot auto-throttle and other equipment that relies on airspeed and altitude information. There have been several commercial flights, more recently Air France's flight 447, whose crash could have been due, in part, to Pitot-static system issues and pilot reaction. It is plausible that the pilot at the controls could have become confused with the erroneous instrument readings of the airspeed and have unknowingly flown the aircraft out of control resulting in the crash. The goal of this article is to help remove or reduce, through knowledge, the likelihood of at least this one link in the chain of problems that can lead to accidents. Table 1 below is provided to summarize -

Airspeed Indicator Calibration

TECHNICAL GUIDANCE MATERIAL AIRSPEED INDICATOR CALIBRATION This document explains the process of calibration of the airspeed indicator to generate curves to convert indicated airspeed (IAS) to calibrated airspeed (CAS) and has been compiled as reference material only. i Technical Guidance Material BushCat NOSE-WHEEL AND TAIL-DRAGGER FITTED WITH ROTAX 912UL/ULS ENGINE APPROVED QRH PART NUMBER: BCTG-NT-001-000 AIRCRAFT TYPE: CHEETAH – BUSHCAT* DATE OF ISSUE: 18th JUNE 2018 *Refer to the POH for more information on aircraft type. ii For BushCat Nose Wheel and Tail Dragger LSA Issue Number: Date Published: Notable Changes: -001 18/09/2018 Original Section intentionally left blank. iii Table of Contents 1. BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................................... 1 2. DETERMINATION OF INSTRUMENT ERROR FOR YOUR ASI ................................................ 2 3. GENERATING THE IAS-CAS RELATIONSHIP FOR YOUR AIRCRAFT....................................... 5 4. CORRECT ALIGNMENT OF THE PITOT TUBE ....................................................................... 9 APPENDIX A – ASI INSTRUMENT ERROR SHEET ....................................................................... 11 Table of Figures Figure 1 Arrangement of instrument calibration system .......................................................... 3 Figure 2 IAS instrument error sample ........................................................................................ 7 Figure 3 Sample relationship between -

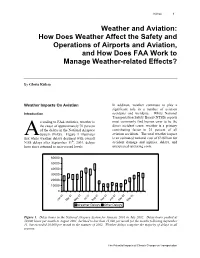

Weather and Aviation: How Does Weather Affect the Safety and Operations of Airports and Aviation, and How Does FAA Work to Manage Weather-Related Effects?

Kulesa 1 Weather and Aviation: How Does Weather Affect the Safety and Operations of Airports and Aviation, and How Does FAA Work to Manage Weather-related Effects? By Gloria Kulesa Weather Impacts On Aviation In addition, weather continues to play a significant role in a number of aviation Introduction accidents and incidents. While National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) reports ccording to FAA statistics, weather is most commonly find human error to be the the cause of approximately 70 percent direct accident cause, weather is a primary of the delays in the National Airspace contributing factor in 23 percent of all System (NAS). Figure 1 illustrates aviation accidents. The total weather impact that while weather delays declined with overall is an estimated national cost of $3 billion for NAS delays after September 11th, 2001, delays accident damage and injuries, delays, and have since returned to near-record levels. unexpected operating costs. 60000 50000 40000 30000 20000 10000 0 1 01 01 0 01 02 02 ul an 01 J ep an 02 J Mar May S Nov 01 J Mar May Weather Delays Other Delays Figure 1. Delay hours in the National Airspace System for January 2001 to July 2002. Delay hours peaked at 50,000 hours per month in August 2001, declined to less than 15,000 per month for the months following September 11, but exceeded 30,000 per month in the summer of 2002. Weather delays comprise the majority of delays in all seasons. The Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Transportation 2 Weather and Aviation: How Does Weather Affect the Safety and Operations of Airports and Aviation, and How Does FAA Work to Manage Weather-related Effects? Thunderstorms and Other Convective In-Flight Icing. -

Sept. 12, 1950 W

Sept. 12, 1950 W. ANGST 2,522,337 MACH METER Filed Dec. 9, 1944 2 Sheets-Sheet. INVENTOR. M/2 2.7aar alwg,57. A77OAMA). Sept. 12, 1950 W. ANGST 2,522,337 MACH METER Filed Dec. 9, 1944 2. Sheets-Sheet 2 N 2 2 %/ NYSASSESSN S2,222,W N N22N \ As I, mtRumaIII-m- III It's EARAs i RNSITIE, 2 72/ INVENTOR, M247 aeawosz. "/m2.ATTORNEY. Patented Sept. 12, 1950 2,522,337 UNITED STATES ; :PATENT OFFICE 2,522,337 MACH METER Walter Angst, Manhasset, N. Y., assignor to Square D Company, Detroit, Mich., a corpora tion of Michigan Application December 9, 1944, Serial No. 567,431 3 Claims. (Cl. 73-182). is 2 This invention relates to a Mach meter for air plurality of posts 8. Upon one of the posts 8 are craft for indicating the ratio of the true airspeed mounted a pair of serially connected aneroid cap of the craft to the speed of sound in the medium sules 9 and upon another of the posts 8 is in which the aircraft is traveling and the object mounted a diaphragm capsuler it. The aneroid of the invention is the provision of an instrument s: capsules 9 are sealed and the interior of the cas-l of this type for indicating the Mach number of an . ing is placed in communication with the static aircraft in fight. opening of a Pitot static tube through an opening The maximum safe Mach number of any air in the casing, not shown. The interior of the dia craft is the value of the ratio of true airspeed to phragm capsule is connected through the tub the speed of sound at which the laminar flow of ing 2 to the Pitot or pressure opening of the Pitot air over the wings fails and shock Waves are en static tube through the opening 3 in the back countered. -

Acnmanual.Pdf

Advanced Coastal Navigation Coast Guard Auxiliary Association Inc. Washington, D. C. First Edition..........................................................................1987 Second Edition .....................................................................1990 Third Edition ........................................................................1999 Fourth Edition.......................................................................2002 ii iii iv v vi Advanced Coastal Navigation TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction...................................................................................................ix Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION TO COASTAL NAVIGATION . .1-1 Chapter 2 THE MARINE MAGNETIC COMPASS . .2-1 Chapter 3 THE NAUTICAL CHART . .3-1 Chapter 4 THE NAVIGATOR’S TOOLS & INSTRUMENTS . .4-1 Chapter 5 DEAD RECKONING . .5-1 Chapter 6 PILOTING . .6-1 Chapter 7 CURRENT SAILING . .7-1 Chapter 8 TIDES AND TIDAL CURRENTS . .8-1 Chapter 9 RADIONAVIGATION . .9-1 Chapter 10 NAVIGATION REFERENCE PUBLICATIONS . .10-1 Chapter 11 FUEL AND VOYAGE PLANNING . .11-1 Chapter 12 REFLECTIONS . .12-1 Appendix A GLOSSARY . .A-1 INDEX . .Index-1 vii Advanced Coastal Navigation viii intRodUction WELCOME ABOARD! Welcome to the exciting world of completed the course. But it does marine navigation! This is the fourth require a professional atti tude, care- edition of the text Advanced Coastal ful attention to classroom presenta- Navigation (ACN), designed to be tions, and diligence in working out used in con cert with the 1210-Tr sample problems. chart in the Public Education (PE) The ACN course has been course of the same name taught by designed to utilize the 1210-Tr nau - the United States Coast Guard tical chart. It is suggested that this Auxiliary (USCGAUX). Portions of chart be readily at hand so that you this text are also used for the Basic can follow along as you read the Coastal Navigation (BCN) PE text. We recognize that students course. -

Beforethe Runway

EDITORIAL Before the runway By Professor Sidney dekker display with fl ight information. My airspeed is leaking out of Editors Note: This time, we decided to invite some the airplane as if the hull has been punctured, slowly defl at- comments on Professor Dekker’s article from subject ing like a pricked balloon. It looks bizarre and scary and the matter experts. Their responses follow the article. split second seems to last for an eternity. Yet I have taught myself to act fi rst and question later in situations like this. e are at 2,000 feet, on approach to the airport. The big So I act. After all, there is not a whole lot of air between me W jet is on autopilot, docile, and responsively follow- and the hard ground. I switch off the autothrottle and shove ing the instructions I have put into the various computer the thrust levers forward. From behind, I hear the engines systems. It follows the heading I gave it, and stays at the screech, shrill and piercing. Airspeed picks up. I switch off altitude I wanted it at. The weather is alright, but not great. the autopilot for good measure (or good riddance) and fl y Cloud base is around 1000 feet, there is mist, a cold driz- the jet down to the runway. It feels solid in my hands and zle. We should be on the ground in the next few minutes. docile again. We land. Then everything comes to a sudden I call for fl aps, and the other pilot selects them for me. -

Soaring Weather

Chapter 16 SOARING WEATHER While horse racing may be the "Sport of Kings," of the craft depends on the weather and the skill soaring may be considered the "King of Sports." of the pilot. Forward thrust comes from gliding Soaring bears the relationship to flying that sailing downward relative to the air the same as thrust bears to power boating. Soaring has made notable is developed in a power-off glide by a conven contributions to meteorology. For example, soar tional aircraft. Therefore, to gain or maintain ing pilots have probed thunderstorms and moun altitude, the soaring pilot must rely on upward tain waves with findings that have made flying motion of the air. safer for all pilots. However, soaring is primarily To a sailplane pilot, "lift" means the rate of recreational. climb he can achieve in an up-current, while "sink" A sailplane must have auxiliary power to be denotes his rate of descent in a downdraft or in come airborne such as a winch, a ground tow, or neutral air. "Zero sink" means that upward cur a tow by a powered aircraft. Once the sailcraft is rents are just strong enough to enable him to hold airborne and the tow cable released, performance altitude but not to climb. Sailplanes are highly 171 r efficient machines; a sink rate of a mere 2 feet per second. There is no point in trying to soar until second provides an airspeed of about 40 knots, and weather conditions favor vertical speeds greater a sink rate of 6 feet per second gives an airspeed than the minimum sink rate of the aircraft. -

Aviation Glossary

AVIATION GLOSSARY 100-hour inspection – A complete inspection of an aircraft operated for hire required after every 100 hours of operation. It is identical to an annual inspection but may be performed by any certified Airframe and Powerplant mechanic. Absolute altitude – The vertical distance of an aircraft above the terrain. AD - See Airworthiness Directive. ADC – See Air Data Computer. ADF - See Automatic Direction Finder. Adverse yaw - A flight condition in which the nose of an aircraft tends to turn away from the intended direction of turn. Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) – A primary FAA publication whose purpose is to instruct airmen about operating in the National Airspace System of the U.S. A/FD – See Airport/Facility Directory. AHRS – See Attitude Heading Reference System. Ailerons – A primary flight control surface mounted on the trailing edge of an airplane wing, near the tip. AIM – See Aeronautical Information Manual. Air data computer (ADC) – The system that receives and processes pitot pressure, static pressure, and temperature to present precise information in the cockpit such as altitude, indicated airspeed, true airspeed, vertical speed, wind direction and velocity, and air temperature. Airfoil – Any surface designed to obtain a useful reaction, or lift, from air passing over it. Airmen’s Meteorological Information (AIRMET) - Issued to advise pilots of significant weather, but describes conditions with lower intensities than SIGMETs. AIRMET – See Airmen’s Meteorological Information. Airport/Facility Directory (A/FD) – An FAA publication containing information on all airports, seaplane bases and heliports open to the public as well as communications data, navigational facilities and some procedures and special notices. -

Use of the MS Flight Simulator in the Teaching of the Introduction to Avionics Course

Session 1928 Use of the MS Flight Simulator in the teaching of the Introduction to avionics course Iulian Cotoi, Ruxandra Mihaela Botez Ecole de technologie supérieure Département de génie de la production automatisée 1100 Notre Dame Ouest Montréal, Qué., Canada, H3C 1K3 Introduction The course Introduction to avionics GPA-745 is an optional course in the Aerospace program given in the Department of Automated Production Engineering at École de technologie supérieure in Montreal, Canada. The main objectif of this course is the study of electronic avionics instrumentation installed in aircraft. In this course, the following chapters are presented : History of avionics, Methods of navigation and orientation, Pilot cockpit and board instrumentation, Communication systems, Radio-navigation systems, Landing systems, Engine signalization instruments, Central alarm systems, Maintenance systems and Warning systems. The presentation of the course in the class to the students is shown on PowerPoint slides and videos on modern aircraft such as Airbus and Boeing. Also, regarding the pilot induced oscillations a video film is provided from Bombardier Aerospace. However, the presentation of the course in the class may be improved and become more efficient grace to the use of MS Flight Simulator. The main idea of this paper is to show how the participation of the students in the class will be increased by use of the MS Flight Simulator. The use of the systems and the electronic board instrumentation will be shown with the help of the new flight simulations modules realized within the MS Flight Simulator. For each instrument, one module will be created and presented in the class, which will result in a more interesting course presentation, stimulating and dynamical from pedagogical point of view, than the theory of the course by use of PowerPoint. -

Hang Glider: Range Maximization the Problem Is to Compute the flight Inputs to a Hang Glider So As to Provide a Maximum Range flight

Hang Glider: Range Maximization The problem is to compute the flight inputs to a hang glider so as to provide a maximum range flight. This problem first appears in [1]. The hang glider has weight W (glider plus pilot), a lift force L acting perpendicular to its velocity vr relative to the air, and a drag force D acting in a direction opposite to vr. Denote by x the horizontal position of the glider, by vx the horizontal component of the absolute velocity, by y the vertical position, and by vy the vertical component of absolute velocity. The airmass is not static: there is a thermal just 250 meters ahead. The profile of the thermal is given by the following upward wind velocity: 2 2 − x −2.5 x u (x) = u e ( R ) 1 − − 2.5 . a m R We take R = 100 m and um = 2.5 m/s. Note, MKS units are used through- out. The upwind profile is shown in Figure 1. Letting η denote the angle between vr and the horizontal plane, we have the following equations of motion: 1 x˙ = vx, v˙x = m (−L sin η − D cos η), 1 y˙ = vy, v˙y = m (L cos η − D sin η − W ) with q vy − ua(x) 2 2 η = arctan , vr = vx + (vy − ua(x)) , vx 1 1 L = c ρSv2,D = c (c )ρSv2,W = mg. 2 L r 2 D L r The glider is controlled by the lift coefficient cL. The drag coefficient is assumed to depend on the lift coefficient as 2 cD(cL) = c0 + kcL where c0 = 0.034 and k = 0.069662. -

Module-7 Lecture-29 Flight Experiment

Module-7 Lecture-29 Flight Experiment: Instruments used in flight experiment, pre and post flight measurement of aircraft c.g. Module Agenda • Instruments used in flight experiments. • Pre and post flight measurement of center of gravity. • Experimental procedure for the following experiments. (a) Cruise Performance: Estimation of profile Drag coefficient (CDo ) and Os- walds efficiency (e) of an aircraft from experimental data obtained during steady and level flight. (b) Climb Performance: Estimation of Rate of Climb RC and Absolute and Service Ceiling from experimental data obtained during steady climb flight (c) Estimation of stick free and fixed neutral and maneuvering point using flight data. (d) Static lateral-directional stability tests. (e) Phugoid demonstration (f) Dutch roll demonstration 1 Instruments used for experiments1 1. Airspeed Indicator: The airspeed indicator shows the aircraft's speed (usually in knots ) relative to the surrounding air. It works by measuring the ram-air pressure in the aircraft's Pitot tube. The indicated airspeed must be corrected for air density (which varies with altitude, temperature and humidity) in order to obtain the true airspeed, and for wind conditions in order to obtain the speed over the ground. 2. Attitude Indicator: The attitude indicator (also known as an artificial horizon) shows the aircraft's relation to the horizon. From this the pilot can tell whether the wings are level and if the aircraft nose is pointing above or below the horizon. This is a primary instrument for instrument flight and is also useful in conditions of poor visibility. Pilots are trained to use other instruments in combination should this instrument or its power fail. -

Aviation Annual Report

2018 Aviation Annual Report Aviation Aircraft Use Summary U.S. Forest Service 2018 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Table 1 – 2018 Forest Service Total Aircraft Available ..................................................................... 2 Introduction: The Forest Service Aviation Program...................................................................................... 3 Aviation Utilization and Cost Information .................................................................................................... 4 2018 At-A-Glance ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Aviation Use .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Table 2 and Figure 1 – Aircraft Total Use CY 2014-2018................................................................... 4 Figure 2 – CY 2018 Flight Hours by Month........................................................................................ 5 Table 3 and Figure 3 – Percent of CY 2018 Flight Time by Aircraft Type .......................................... 5 Table 4 – CY 2018 Aircraft Use by Region/Agency ............................................................................ 6 Aviation Cost ........................................................................................................................................