And Painted Turtle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life History Account for Western Pond Turtle

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group WESTERN POND TURTLE Actinemys marmorata Family: EMYDIDAE Order: TESTUDINES Class: REPTILIA R004 Written by: S. Morey Reviewed by: T. Papenfuss Edited by: R. Duke Updated by: CWHR Program Staff, March 2000 DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY The western pond turtle is uncommon to common in suitable aquatic habitat throughout California, west of the Sierra-Cascade crest and absent from desert regions, except in the Mojave Desert along the Mojave River and its tributaries. Elevation range extends from near sea level to 1430 m (4690 ft) (Jennings and Hayes 1994). Associated with permanent or nearly permanent water in a wide variety of habitat types. SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: This species is considered omnivorous. Aquatic plant material, including pond lilies, beetles and a variety of aquatic invertebrates as well as fishes, frogs, and even carrion have been reported among their food (Stebbins 1972, Nussbaum et al. 1983). Cover: Pond turtles require basking sites such as partially submerged logs, rocks, mats of floating vegetation, or open mud banks. Turtles slip from basking sites to underwater retreats at the approach of humans or potential predators. Hibernation in colder areas is passed underwater in bottom mud. Reproduction: Storer (1930) suggested that two distinct habitats may be used for oviposition. Along large slow-moving streams, eggs are deposited in nests constructed in sandy banks. Along foothill streams, females may climb hillsides, sometimes moving considerable distances to find a suitable nest site. Nussbaum et al. (1983) reports a nest in a clover field 100 m (325 ft) from water. -

Competing Generic Concepts for Blanding's, Pacific and European

Zootaxa 2791: 41–53 (2011) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2011 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Competing generic concepts for Blanding’s, Pacific and European pond turtles (Emydoidea, Actinemys and Emys)—Which is best? UWE FRITZ1,3, CHRISTIAN SCHMIDT1 & CARL H. ERNST2 1Museum of Zoology, Senckenberg Dresden, A. B. Meyer Building, D-01109 Dresden, Germany 2Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, MRC 162, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012, USA 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We review competing taxonomic classifications and hypotheses for the phylogeny of emydine turtles. The formerly rec- ognized genus Clemmys sensu lato clearly is paraphyletic. Two of its former species, now Glyptemys insculpta and G. muhlenbergii, constitute a well-supported basal clade within the Emydinae. However, the phylogenetic position of the oth- er two species traditionally placed in Clemmys remains controversial. Mitochondrial data suggest a clade embracing Actinemys (formerly Clemmys) marmorata, Emydoidea and Emys and as its sister either another clade (Clemmys guttata + Terrapene) or Terrapene alone. In contrast, nuclear genomic data yield conflicting results, depending on which genes are used. Either Clemmys guttata is revealed as sister to ((Emydoidea + Emys) + Actinemys) + Terrapene or Clemmys gut- tata is sister to Actinemys marmorata and these two species together are the sister group of (Emydoidea + Emys); Terra- pene appears then as sister to (Actinemys marmorata + Clemmys guttata) + (Emydoidea + Emys). The contradictory branching patterns depending from the selected loci are suggestive of lineage sorting problems. Ignoring the unclear phy- logenetic position of Actinemys marmorata, one recently proposed classification scheme placed Actinemys marmorata, Emydoidea blandingii, Emys orbicularis, and Emys trinacris in one genus (Emys), while another classification scheme treats Actinemys, Emydoidea, and Emys as distinct genera. -

Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys Picta)

Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta) Class: Reptilia Order: Testudines Family: Emydidae Characteristics: The most widespread native turtle of North America. It lives in slow-moving fresh waters, from southern Canada to Louisiana and northern Mexico, and from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The adult painted turtle female is 10–25 cm (4–10 in) long; the male is smaller. The turtle's top shell is dark and smooth, without a ridge. Its skin is olive to black with red, orange, or yellow stripes on its extremities. The subspecies can be distinguished by their shells: the eastern has straight-aligned top shell segments; the midland has a large gray mark on the bottom shell; the southern has a red line on the top shell; the western has a red pattern on the bottom shell (Washington Nature Mapping Program). Behavior: Although they are frequently consumed as eggs or hatchlings by rodents, canines, and snakes, the adult turtles' hard shells protect them from most predators. Reliant on warmth from its surroundings, the painted turtle is active only during the day when it basks for hours on logs or rocks. During winter, the turtle hibernates, usually in the mud at the bottom of water bodies. Reproduction: The turtles mate in spring and autumn. Females dig nests on land and lay eggs between late spring and mid- summer. Hatched turtles grow until sexual maturity: 2–9 years for males, 6–16 for females. Diet: Wild: aquatic vegetation, algae, and small water creatures including insects, crustaceans, and fish Zoo: Algae, duck food Conservation: While habitat loss and road killings have reduced the turtle's population, its ability to live in human-disturbed settings has helped it remain the most abundant turtle in North America. -

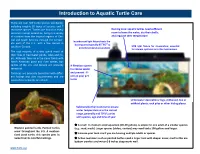

Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care

Mississippi Map Turtle Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care There are over 300 turtle species worldwide, including roughly 60 types of tortoise and 7 sea turtle species. Turtles are found on every Basking area: aquatic turtles need sufficient continent except Antarctica, living in a variety room to leave the water, dry their shells, of climates from the tropical regions of Cen- and regulate their temperature. tral and South America through the temper- Incandescent light fixture heats the ate parts of the U.S., with a few species in o- o) basking area (typically 85 95 to UVB light fixture for illumination; essential southern Canada. provide temperature gradient for vitamin synthesis in turtles held indoors The vast majority of turtles spend much of their lives in freshwater ponds, lakes and riv- ers. Although they are in the same family with North American pond and river turtles, box turtles of the U.S. and Mexico are primarily A filtration system terrestrial. to remove waste Tortoises are primarily terrestrial with differ- and prevent ill- ent habitat and diet requirements and are ness in your pet covered in a separate care sheet. turtle Underwater decorations: logs, driftwood, live or artificial plants, rock piles or other hiding places. Submersible thermometer to ensure water temperature is in the correct range, generally mid 70osF; varies with species, age and time of year A small to medium-sized aquarium (20-29 gallons) is ample for one adult of a smaller species Western painted turtle. Painted turtles (e.g., mud, musk). Larger species (sliders, cooters) may need tanks 100 gallons and larger. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

The Western Pond Turtle: Habitat and History

THE WESTERN POND TURTLE: HABITAT AND HISTORY FINAL REPORT Prepared by: Dan C. Holland, PhD Wildlife Diversity Program Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Portland, OR Prepared for: U. S. Department ofEnergy Bonneville Power Administration Environment, Fish and Wildlife P. O. Box 3621 Portland, OR 97208-3 62 1 Project Number 92-068 Contract Number DE-BI79-92BP62 137 August 1994 TABLE OF CONTENTSf1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Pat,:e Chapter 1 A Brief Overview of the Evolution of the Willamette-Puget Sound Hydrographic Basin Introduction .1-3 The Biotic Landscape ofthe Willamette Valley in the Holocene .1-7 The Historical Appearance of the Willamette Valley ca: 18 10- 1860 .1-15 The Influence ofHumans on the Biotic Landscape ofthe Willamette Valley .1-19 Changes in the Biotic Landscape: 1840's-1940' .1-22 Literature Cited .1-31 Chapter 2 A Synopsis of the Natural History of the Western Pond Turtle Taxonomy 2-3 Description , 2-3 Range 2-4 Distribution-Oregon 2-4 Behavior 2-5 Diet 2-5 Home Range 2-6 Activity '" 2-6 Habitat Requirements--Aquatic Habitats .2-7 Habitat Requirements--Terrestrial Habitats .2-8 Overland Movements 2-9 Reproduction 2-9 Growth and Survivorship .2-11 Predation and Mortality 2-11 Disease 2-13 Parasites 2-14 Drought. .2-14 Literature Cited .2-15 Chapter 3 Methods 3-1 Chapter 4 Status of the Western Pond Turtle in the Willamette Drainage Historical Background 4-3 Recent Studies 4-4 Survey Effort Goals 4-4 Overall Results 4-5 Other Studies 4-5 Locality Data 4-6 Population Structure 4-6 Population Size 4-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS/2 -

Painted Turtle

United States Turtle Mapping Project with a Focus on Western Pond Turtle and Painted Turtle Kimberly Barela BioResource Research Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR Deanna H. Olson, Ph.D. U.S. Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Corvallis, OR Photo by: Jennifer Gervais Background 220 million years (older than Triassic) Survived several geological changes 48% of 328 recognized turtle species are Threatened • 27% of these are Critically Endangered or Endangered Image From :http://animaldiversity.org. (Olson et. al., 2011), (Turtle Taxonomy Working Group 2010) Turtles Are SLOW Movement • Relatively small range Reproduction • Maturity: 4-15 years • Western Pond Turtle: 5-10 years Slow movement + Reproduction = Vulnerable species Image From :http://david-merritt.blogspot.com/2011/07/insight-pausing-and-retrying-messages.html (Olson et. al., 2011) Turtle Threats Habitat loss Road mortality Predation Over-exploitation Recreation disturbances Image From :http://envs.uoregon.edu/elp/turtles/doku.php?id=wpt_conservation (2nd); http://linkinglandscapes.info/ roads/roads.html (1st); Reptilecare.com & Natural-enivironment.com. (3rd), Dan Rosenberg (4th) (Rosenberg et. al. 2009) Why Should We Care? Cultural Ecological Images From: http://www.oneidaindiannation.com/history/creationstory (Lower Left), Everett Collection (Upper Right) http://mdk12.org/instruction/clg/public_release/biology/G3_E5_I3.html (Center), Year of the Turtle Diamondback Terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) Red-eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans) Desert -

Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys

Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Steven P. Krichbaum May 2018 © 2018 Steven P. Krichbaum. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians by STEVEN P. KRICHBAUM has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Willem Roosenburg Professor of Biological Sciences Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 Abstract KRICHBAUM, STEVEN P., Ph.D., May 2018, Biological Sciences Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians Director of Dissertation: Willem Roosenburg My study presents information on summer use of terrestrial habitat by IUCN “endangered” North American Wood Turtles (Glyptemys insculpta), sampled over four years at two forested montane sites on the southern periphery of the species’ range in the central Appalachians of Virginia (VA) and West Virginia (WV) USA. The two sites differ in topography, stream size, elevation, and forest composition and structure. I obtained location points for individual turtles during the summer, the period of their most extensive terrestrial roaming. Structural, compositional, and topographical habitat features were measured, counted, or characterized on the ground (e.g., number of canopy trees and identification of herbaceous taxa present) at Wood Turtle locations as well as at paired random points located 23-300m away from each particular turtle location. -

Surveys for Western Pond Turtle Actinemys Marmorata on The

Surveys for Western pond turtle Actinemys marmorata On the Siuslaw National Forest Cynthia G. Burns, Wildlife Biologist U. S. Forest Service Siuslaw National Forest October 29, 2010 SUMMARY Surveys were contracted to establish presence of the western pond turtle (Actinemys marmorata) on lands within or adjacent to the Siuslaw National Forest’s (SNF) Hebo and Central Coast/ODNRA (Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area) Ranger Districts during the summer of 2010. Portions of 5 rivers and 1 lake were surveyed on or near the Central Coast/Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area (ODNRA) Ranger District and 3 lakes were surveyed on the Hebo District. Surveys were conducted by kayak and at fixed points. Two Red-eared Sliders Trachemys scripta elegans were confirmed during contracted surveys. No western pond turtles were found. Habitat and invasive species data were also collected as part of the survey effort. INTRODUCTION The western pond turtle occurs along the Pacific states from Baja California to Puget Sound of Washington. Western pond turtles are listed as endangered in Washington, sensitive critical in Oregon and are a species of concern in Region 6 of the Forest Service (WA & OR). It was proposed for Federal listing in 1991 but was precluded due to lack of supporting evidence on its population trends. In 2010 the Siuslaw National Forest continued surveys of lands within or adjacent to its boundaries in an effort to determine where individuals or populations may still exist. In Oregon, the western pond turtle occurs primarily within the drainages of the Willamette, Umpqua, Rogue and Klamath Rivers but has also been documented in lowland aquatic habitats throughout western Oregon (Rosenberg, 2009). -

In AR, FL, GA, IA, KY, LA, MO, OH, OK, SC, TN, and TX): Species in Red = Depleted to the Point They May Warrant Federal Endangered Species Act Listing

Southern and Midwestern Turtle Species Affected by Commercial Harvest (in AR, FL, GA, IA, KY, LA, MO, OH, OK, SC, TN, and TX): species in red = depleted to the point they may warrant federal Endangered Species Act listing Common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) – AR, GA, IA, KY, MO, OH, OK, SC, TX Florida common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina osceola) - FL Southern painted turtle (Chrysemys dorsalis) – AR Western painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) – IA, MO, OH, OK Spotted turtle (Clemmys gutatta) - FL, GA, OH Florida chicken turtle (Deirochelys reticularia chrysea) – FL Western chicken turtle (Deirochelys reticularia miaria) – AR, FL, GA, KY, MO, OK, TN, TX Barbour’s map turtle (Graptemys barbouri) - FL, GA Cagle’s map turtle (Graptemys caglei) - TX Escambia map turtle (Graptemys ernsti) – FL Common map turtle (Graptemys geographica) – AR, GA, OH, OK Ouachita map turtle (Graptemys ouachitensis) – AR, GA, OH, OK, TX Sabine map turtle (Graptemys ouachitensis sabinensis) – TX False map turtle (Graptemys pseudogeographica) – MO, OK, TX Mississippi map turtle (Graptemys pseuogeographica kohnii) – AR, TX Alabama map turtle (Graptemys pulchra) – GA Texas map turtle (Graptemys versa) - TX Striped mud turtle (Kinosternon baurii) – FL, GA, SC Yellow mud turtle (Kinosternon flavescens) – OK, TX Common mud turtle (Kinosternon subrubrum) – AR, FL, GA, OK, TX Alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii) – AR, FL, GA, LA, MO, TX Diamond-back terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) – FL, GA, LA, SC, TX River cooter (Pseudemys concinna) – AR, FL, -

Western Pond Turtle Summer Habitat Use in a Coastal Watershed

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2010 Western Pond Turtle Summer Habitat Use in a Coastal Watershed Jae Abel San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Abel, Jae, "Western Pond Turtle Summer Habitat Use in a Coastal Watershed" (2010). Master's Theses. 3741. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.bp29-6fvm https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3741 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WESTERN POND TURTLE SUMMER HABITAT USE IN A COASTAL WATERSHED A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Biology San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Jae Abel May 2010 i © 2010 Jae Abel ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled WESTERN POND TURTLE SUMMER HABITAT USE IN A COASTAL WATERSHED By Jae Abel APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGY SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY May 2010 Dr. Jerry J. Smith Department of Biological Sciences Dr. Nishanta Rajakaruna Department of Biological Sciences Dr. Paula Messina Department of Geology Dr. Sean Hayes NOAA-National Marine Fisheries Service iii ABSTRACT WESTERN POND TURTLE SUMMER HABITAT USE IN A COASTAL WATERSHED by Jae Abel Western pond turtle ( Actinemys marmorata ) habitat use was studied in a coastal pond, lagoon, and stream system during the summer of 1995 and 1996 at Waddell Creek, Santa Cruz County, California. -

Box Turtle (Terrapene Carolina) Phillip Demaynadier

STATE ENDANGERED Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) Phillip deMaynadier Description would most likely occur in the southwestern part of Box turtles are well-known for their remarkable the state. A few individual box turtles have been ability to seal themselves tightly in their shell during found in the last 20 years as far north as New times of danger. The box turtle is distinguished by a Vinyard in Franklin County and Hermon in brownish carapace (upper shell). Each scute (seg- Penobscot County, although these may have been ment of the shell) has yellow or orange radiating released pets. lines, spots, or blotches. The legs and neck have Box turtles are the most terrestrial turtle in the black to reddish-brown skin with yellow, red, or state. They prefer moist woodlands and wet, brushy orange spots and streaks. The plastron (lower shell) fields, especially where sandy soils are prevalent. Box is tan to dark brown. The box turtle’s most distinc- turtles occasionally are found in meadows, bogs, and tive feature is a hinged plastron, allowing the animal marshes. to withdraw its legs and head entirely within a tightly closed shell. Males have red eyes, a concave Life History and Ecology plastron, a thick tail, and long, curved claws on the Box turtles emerge from hibernation in late hind feet. Females have yellowish-brown eyes; a flat April or early May following the first warm spring or slightly convex plastron; a carapace that is more rains. They attain sexual maturity at 5-10 years old. domed than the male’s; short, slender, straighter Once they reach maturity, they mate anytime claws on the hind feet; and a shorter, thinner tail.