The Revelation at Sinai in Bible and Midrash Everett Fox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The God Who Delivers (Part 2)

The God Who Delivers (part 2) Review from Creation to Jacob’s family in Egypt? Our last study ended the book of Genesis with Joseph enjoying life as the Pharoah’s commanding officer. After forgiving his brothers for what they had done, Jacob and his entire clan moves to Egypt and this is where the book of Exodus begins. What turn of event occurs in the life of the Israelites in Egypt? Exodus 1:8-11 A generation passes and new powers come to be. A new pharaoh “whom Joseph meant nothing” became fearful the Israelite nation, becoming so fruitful and huge, would rebel against him. The Israelites became slaves to the Egyptians. The Pharoah comes up with what solution? 1:22 Kill every Hebrew boy that is born. The future deliverer is delivered. 2:1-10. A boy is spared, saved from a watery death through the means of an “ark”. Sound familiar? Moses is delivered to one day deliver God’s people out of Egypt, but for the time being, was being brought up in the Egyptian royal household. Moses becomes an enemy to Egypt. 2:11-15. Moses tries to do what is right, but has to flee Egypt for his life so he goes to Mdian. God has a message for Moses. Chapter 3. The Lord tells Moses he will be the one to deliver the Israelites out of slavery, but Moses immediately doubts. 3:11. God tells Moses who He is. 3:14-15. I am who I am. God gives Moses special abilities in order to convince the people. -

The Two Screens: on Mary Douglas S Proposal

The Two Screens: On Mary Douglass Proposal for a Literary Structure to the Book of Leviticus* Gary A. Rendsburg In memoriam – Mary Douglas (1921–2007) In the middle volume of her recent trio of monographs devoted to the priestly source in the Torah, Mary Douglas proposes that the book of Leviticus bears a literary structure that reflects the layout and config- uration of the Tabernacle.1 This short note is intended to supply further support to this proposal, though first I present a brief summary of the work, its major suppositions, and its principal finding. The springboard for Douglass assertion is the famous discovery of Ramban2 (brought to the attention of modern scholars by Nahum Sar- na3) that the tripartite division of the Tabernacle reflects the similar tripartite division of Mount Sinai. As laid out in Exodus 19 and 24, (a) the people as a whole occupied the lower slopes; (b) Aaron, his two sons, and the elders were permitted halfway up the mountain; and (c) only Moses was allowed on the summit. In like fashion, according to the priestly instructions in Exodus 25–40 and the book of Leviticus, (a) the people as a whole were allowed to enter the outer court of the Taberna- * It was my distinct pleasure to deliver an oral version of this article at the Mary Douglas Seminar Series organized by the University of London in May 2005, in the presence of Professor Douglas and other distinguished colleagues. I also take the op- portunity to thank my colleague Azzan Yadin for his helpful comments on an earlier version of this article. -

Covenant of Mount Sinai

mark h lane www.biblenumbersforlife.com COVENANT OF MOUNT SINAI SUMMARY The children of Israel were slaves in Egypt. The Lord brought them out with a mighty hand and with an outstretched arm. He brought them into the desert of Sinai and made them a nation under God, with the right to occupy and live in the Promised Land, AS TENANTS, subject to obedience to the Law of Moses. To have the privilege to continue to occupy the Promised Land Israel must keep: The ritual law concerning the priesthood and the continual offering of animal sacrifices, etc. The civil law concerning rights of citizens, land transactions, execution of justice, etc. The moral law: Love your neighbor as yourself The heart law: Love the LORD your God and serve him only In the Law of Moses there were blessings for obedience and curses for disobedience. Penalties for disobedience went as far as being shipped back to Egypt as slaves. All who relied on observing the Law of Moses were under a curse. It is written: “Cursed is everyone who does not continue to do everything written in the Book of the Law” (Deut. 27:26). None of the blessings under the Law of Moses concern eternal life, the heavenly realm, or the forgiveness of sins necessary to stand before God in the life hereafter. The people under the Covenant of Sinai did not even enjoy the privilege of speaking to the Lord face to face. The high priest, who crawled into the Most Holy Place once a year, was required to fill the room with incense so that he would not see the LORD and die. -

Torah Texts Describing the Revelation at Mt. Sinai-Horeb Emphasize The

Paradox on the Holy Mountain By Steven Dunn, Ph.D. © 2018 Torah texts describing the revelation at Mt. Sinai-Horeb emphasize the presence of God in sounds (lwq) of thunder, accompanied by blasts of the Shofar, with fire and dark clouds (Exod 19:16-25; 20:18-21; Deut 4:11-12; 5:22-24). These dramatic, awe-inspiring theophanies re- veal divine power and holy danger associated with proximity to divine presence. In contrast, Elijah’s encounter with God on Mt. Horeb in 1 Kings 19:11-12, begins with a similar audible, vis- ual drama of strong, violent winds, an earthquake and fire—none of which manifest divine presence. Rather, it is hqd hmmd lwq, “a voice of thin silence” (v. 12) which manifests God, causing Elijah to hide his face in his cloak, lest he “see” divine presence (and presumably die).1 Revelation in external phenomena present a type of kataphatic experience, while revelation in silence presents a more apophatic, mystical experience.2 Traditional Jewish and Christian mystical traditions point to divine silence and darkness as the highest form of revelatory experience. This paper explores the contrasting theophanies experienced by Moses and the Israelites at Sinai and Elijah’s encounter in silence on Horeb, how they use symbolic imagery to convey transcendent spiritual realities, and speculate whether 1 Kings 19:11-12 represents a “higher” form of revela- tory encounter. Moses and Israel on Sinai: Three months after their escape from Egypt, Moses leads the Israelites into the wilderness of Sinai where they pitch camp at the base of Mt. -

Tabernacle, the Golden Calf, and Covenant Renewal Exodus 25-40 – Lesson 18 Wednesday, September 2, 2020

EXODUS: Tabernacle, the Golden Calf, and Covenant Renewal Exodus 25-40 – Lesson 18 Wednesday, September 2, 2020 Quite possibly this is the last major unit of Exodus (dealing with the tabernacle), this section probably seems tedious, for many modern readers of the Old Testament. Nevertheless, Scripture has given us an intricate description of the tabernacle, a description that ranges over sixteen chapters, from divine orders to build (25-31), to interruption and delay of implementation because of apostasy (32-34), to final execution of the divine mandate (35-40). The movement is from instruction (25-31) to interruption (32-34) to implementation (35-40). Sandwiched in between two sections (25-31 and 35-40) that deal with proper worship of God and building what God wants his people to build is a section (32-34) that deals with improper worship of God and building/making what God does not want his people to build/make. One may also discern that Exodus begins and ends with Israelites building something. At the beginning that are forced to build stores cities for Pharaoh (1:11); at the end they choose to build a portable place of worship where God may dwell in their midst. Theological Analysis In the tabernacle there were seven pieces of furniture. The article of clothing worn by those officiating in the tabernacle numbered eight, four of which are worn by the high priest alone (the ephod 28:6-12); (the breastpiece of judgment 28:15-30); (the ephod’s robe (28:31-35); (a turban 28:36-38), and four more that are worn by all the priests (a coat, gridle, cap, and linen breeches 28:40-42). -

![1/10 of an Eifa ]=עשרון . וְהָ עֹמֶ ר, עֲ שִׂ רִׂ ית הָ אֵ יפָ ה הּוא](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1918/1-10-of-an-eifa-681918.webp)

1/10 of an Eifa ]=עשרון . וְהָ עֹמֶ ר, עֲ שִׂ רִׂ ית הָ אֵ יפָ ה הּוא

Omer, Shemitta, & Har Sinai – what’s the connection? source sheet for lecutre by Menachem Leibtag, www.tanach.org A. “OMER” – something to count, or something to eat! 1. Manna – as preparation for Mount Sinai /Shmot 16:1-4 16:1 They moved on from Elim, and the entire community of Israel came to the Sin Desert, between Elim and Sinai. It was the 15th of the second month after they had left Egypt. 16:2 There in the desert, the entire Israelite community began to complain against Moses and Aaron. 16:3 The Israelites said to them, 'If only we had died by God's hand in Egypt! There at least we could sit by pots of meat and eat our fill of bread! But you had to bring us out to this desert, to kill the entire community by starvation!' 16:4 God said to Moses, 'I will make bread rain down to you from the sky. The people will go out and gather enough for each day, so. I will test them to see whether or not they will keep My law. 2. Taking as much as one ‘needs’, but not on shabbat / see 16:16-18 16:16 God's instructions are that each man shall take as much as he needs. There shall be an omer for each person, according to the number of people each man has in his tent.' 16:18 And they measured it with an omer, the one who had taken more did not have any extra, and the one who had taken less did not have too little. -

Why Did Moses Break the Tablets (Ekev)

Thu 6 Aug 2020 / 16 Av 5780 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Torah discussion on Ekev Why Did Moses Break the Tablets? Introduction In this week's portion, Ekev, Moses recounts to the Israelites how he broke the first set of tablets of the Law once he saw that they had engaged in idolatry by building and worshiping a golden calf: And I saw, and behold, you had sinned against the Lord, your God. You had made yourselves a molten calf. You had deviated quickly from the way which the Lord had commanded you. So I gripped the two tablets, flung them away with both my hands, and smashed them before your eyes. [Deut. 9:16-17] This parallels the account in Exodus: As soon as Moses came near the camp and saw the calf and the dancing, he became enraged; and he hurled the tablets from his hands and shattered them at the foot of the mountain. [Exodus 32:19] Why did he do that? What purpose did it accomplish? -Wasn’t it an affront to God, since the tablets were holy? -Didn't it shatter the authority of the very commandments that told the Israelites not to worship idols? -Was it just a spontaneous reaction, a public display of anger, a temper tantrum? Did Moses just forget himself? -Why didn’t he just return them to God, or at least get God’s approval before smashing them? Yet he was not admonished! Six explanations in the Sources 1-Because God told him to do it 1 The Talmud reports that four prominent rabbis said that God told Moses to break the tablets. -

Moses Meets God on the Mountain 10 – 16 OCT 2017

Moses Meets God on the Mountain 10 – 16 OCT 2017 EX 19 - 40 Week 4 --- 46 Weeks to Go God reveals, through Moses, his law and how he is to be worshipped. The Mosaic covenant (the 10 commandments and the Book of the Covenant) reveal God’s justice and righteousness, basic principles of ethics and morality, people’s choice and responsibility, and God’s concern for the poor, helpless and oppressed. God’s desire to be present among his people is revealed in the construction and regulations regarding the tabernacle and worship. Exodus emphasizes God’s holiness.. The central character of this book, Moses, is the mediator between God and his people, pointing ahead to Christ our own great mediator. Weekly Reading Plan Outline Day 1: EX 19:1 – 21:36 The Covenant at Sinai (Days 1-7) Day 2: EX 22:1 – 24:18 Divine Worship (Days 2-7) Day 3: EX 25:1 – 27:21 God’s Glory (Day 7) Day 4: EX 28:1 – 29:46 Day 5: EX 30:1 – 32:35 Day 6: EX 33:1 – 35:35 Day 7: EX 36:1 – 40:38 Key Characters Key Locations Key Terms Moses Mt. Sinai Covenant Aaron The desert Ten Commandments The Tabernacle Tabernacle Joshua Priests The Israelites The Law Bezalel Sabbath Oholiab Holy, Holiness Offerings Book of the Covenant Ark of the Covenant Cloud of glory Key Verses You yourselves have seen what I did to Egypt and how I carried you on eagles’ wings and brought you to myself. Now the, if you will indeed obey My voice and keep My covenant, then you shall be My own possession among all the peoples, for all the earth is Mine. -

A Holy and Powerful Savior

THE TRANSFIGURATION OF OUR LORD February 23, 2020 A Holy and Powerful Savior Welcome! Thank you for joining us for worship this morning. We are happy that you are here! HELPFUL INFORMATION New to Our Savior? We are thrilled that you have joined us for worship today. Please take a moment to fill out a Connect Card—if you would prefer to fill it out online, scan the code with your phone, or go to OurSaviorBirmingham.com/Connect. You can put the Connect Card in the offering plate or give it to an usher as you leave. Bathrooms are located at the far end of the hallway as you exit the sanctuary. There is a changing station located in Room 3 (Nursery). Families with kids: We think it is important for families to worship together regularly. We know that occasionally, kids are going to have a rough morning. If your little one needs a moment, there is a speaker and window in our entryway that will allow you to see and hear the service. Children’s Activity Sheets give activities and lessons pertaining to the Scripture lessons for today’s service. Ask an usher at the door into the sanctuary. Holy Communion will be celebrated as part of this morning’s worship service. Here at Our Savior Lutheran Church, we practice “membership communion” and ask that only members come forward to receive the sacrament. An offering will be taken during our worship service today. If you are a guest, please do not feel obligated or compelled to participate. If you would like to give an offering that supports the ministry work at Our Savior, there are several ways to make a tax-deductible contribution: (1) place your offering into the offering plate, (2) you can scan this QR code to take you to our secure, online giving site where you can give via credit card or ACH transfer. -

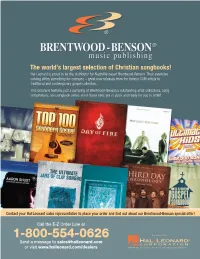

The World's Largest Selection of Christian Songbooks!

19424 BrentBenBroch 9/25/07 10:09 AM Page 1 The world’s largest selection of Christian songbooks! Hal Leonard is proud to be the distributor for Nashville-based Brentwood-Benson. Their extensive catalog offers something for everyone – great new releases from the hottest CCM artists to traditional and contemporary gospel collection. This brochure features just a sampling of Brentwood-Benson’s outstanding artist collections, song compilations, and songbook series. All of these titles are in stock and ready for you to order! Contact your Hal Leonard sales representative to place your order and find out about our Brentwood-Benson special offer! Call the E-Z Order Line at 1-800-554-0626 Send a message to [email protected] or visit www.halleonard.com/dealers 19424 BrentBenBroch 9/25/07 10:09 AM Page 2 MIXED FOLIOS Amazing Wedding Songs Top 100 Praise and Worship Top 100 Praise & Worship Top 100 Southern Gospel 30 of the Most Requested Songs – Volume 2 Songbook Songbook BRENTWOOD-BENSON Songs for That Special Day This guitar chord songbook includes: Ah, Lord Guitar Chord Songbook Lyrics, chord symbols and guitar chord dia- Book/CD Pack God • Celebrate Jesus • Glorify Thy Name • Lyrics, chord symbols and guitar chord dia- grams for 100 classics, including: Because He Listening CD – 5 songs Great Is Thy Faithfulness • How Majestic Is grams for 100 songs, including: As the Deer • Lives • Daddy Sang Bass • Gettin’ Ready to ✦ Includes: Always • Ave Maria • Butterfly Your Name • In the Presence of Jehovah • My Come, Now Is the Time to Worship • I Could Leave This World • He Touched Me • In the Kisses • Canon in D • Endless Love • I Swear Savior, My God • Soon and Very Soon • Sing of Your Love Forever • Lord, I Lift Your Sweet By and By • I’ve Got That Old Time • Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring • Love Will Be Victory Chant • We Have Come into This Name on High • Open the Eyes of My Heart • Religion in My Heart • Just a Closer Walk with Our Home • Ode to Joy • The Keeper of the House • and many more! Rock of Ages • and dozens more. -

Exodus at a Glance

Scholars Crossing The Owner's Manual File Theological Studies 11-2017 Article 2: Exodus at a Glance Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "Article 2: Exodus at a Glance" (2017). The Owner's Manual File. 44. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual/44 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Owner's Manual File by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXODUS AT A GLANCE This book describes Israel’s terrible bondage in Egypt, its supernatural deliverance by God, its journey from the Red Sea to the base of Mt. Sinai as led by Moses, the giving of the Law, the terrible sin of worshiping the golden calf, and the completion of the Tabernacle. BOTTOM LINE INTRODUCTION HOW ODD OF GOD TO CHOOSE THE JEWS! THE STORY OF HOW HE SELECTED THEM PROTECTED THEM, AND DIRECTED THEM. FACTS REGARDING THE AUTHORS OF THIS BOOK 1. Who? Moses. He was the younger brother of Aaron and Miriam (Ex. 6:20; Num. 26:59) who led his people Israel out of Egyptian bondage (Ex. 5-14) and gave them the law of God at Mt. Sinai (Ex. 20). 2. What? That books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. -

MOSES and the 10 COMMANDMENTS at Mount Sinai, the People of Israel Were Finally About to Meet with God

bible stories MOSES AND THE 10 COMMANDMENTS At Mount Sinai, the people of Israel were finally about to meet with God. God was going to give them His good and helpful law, the 10 Commandments. by Shelby Faith In the third month after Israel left Egypt, the Israelites came to the Wilderness of Sinai. They camped there before the mountain. God told Moses to come up to the mountain. So Moses went up to God. God said, “Tell the people of Israel: ‘You have seen what I did to the Egyptians, and how I brought you out of Egypt. Now, if you will obey My voice and keep My covenant, then you shall be special to Me above all people.” Moses returned and called for the elders of the people. He told them God would make an agreement with Israel and take care of them if they obeyed His words. The people said, “We will do all that the Lord wants us to do.” Moses went back to God and told Him what the people had said. Then God said to Moses, “Tell the people to wash their clothes and be ready for the third day. On the third day I will come down on Mount Sinai. Tell them not to go up to the mountain or touch it. Anyone who touches the mountain will die. When the trumpet sounds long, they shall come near the mountain.” Again Moses went down from the mountain and got the people ready. God speaks from Mount Sinai Now on the third day there was great thunder and lightning.