Gender References in Rap Lyrics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hip Hop Pedagogies of Black Women Rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Guillory, Nichole Ann, "Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 173. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/173 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SCHOOLIN’ WOMEN: HIP HOP PEDAGOGIES OF BLACK WOMEN RAPPERS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Nichole Ann Guillory B.S., Louisiana State University, 1993 M.Ed., University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 1998 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 Nichole Ann Guillory All Rights Reserved ii For my mother Linda Espree and my grandmother Lovenia Espree iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am humbled by the continuous encouragement and support I have received from family, friends, and professors. For their prayers and kindness, I will be forever grateful. I offer my sincere thanks to all who made sure I was well fed—mentally, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. I would not have finished this program without my mother’s constant love and steadfast confidence in me. -

Lil' Kim the Notorious KIM Mp3, Flac, Wma

Lil' Kim The Notorious KIM mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: The Notorious KIM Country: Bulgaria Released: 2000 MP3 version RAR size: 1407 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1108 mb WMA version RAR size: 1466 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 514 Other Formats: AAC VOC MMF MOD ADX MP1 AIFF Tracklist Hide Credits Lil' Drummer Boy Featuring – Cee-Lo, RedmanMixed By – Ed RasoProducer – Mario "Yellowman" Winans*, A1 4:31 Sean "Puffy" Combs*Recorded By – Caram Costanzo, Ed RasoWritten-By – M. Winans*, R. Noble*, T. Burton* Custom Made (Give It To You) A2 Co-producer – Daniel GlogowerMixed By – Axel Nielhaus*Producer – Fury*Recorded By – 3:06 Ed RasoWritten-By – D. Glogower*, L. Marvin Burns*, N. Loftin* Who's Number One? Mixed By – Prince Charles AlexanderProducer – Jerome "Knowbody" Foster*, Richard A3 "Younglord" Frierson*Rap [Additional] – Puff DaddyRecorded By – Tony 4:13 Masserati*Scratches – Marc PfafflinWritten-By – A. Poree*, F. Wilson*, L. Caston*, R. Frierson* Suck My D**k Mixed By – Stephen DentProducer – Mas , RATED R*Rap [Additional] – Mr. Bristal*Written A4 4:04 By – MorganWritten-By – Donalds*, Glover*, Wallace*, Thompson*, Troutman*, Troutman*, Combs*, Murdock* Single Black Female Acoustic Guitar – James "Linus" Dotson*Mixed By – Rob PaustianProducer, Featuring – A5 4:14 Mario "Yellowman" Winans*Recorded By – Shannon "Slam" LawrenceWritten-By – M. Winans* Revolution Effects [Sound] – Marc PfafflinFeaturing – Grace Jones, Lil' CeaseMixed By – Ed Raso, A6 Prince Charles Alexander, Stephen DentProducer – Mario "Yellowman" Winans*, Sean 4:54 "Puffy" Combs*Rap [Additional] – Puff DaddyRecorded By – Prince Charles Alexander, Roger CheWritten-By – M. Winans*, S. Combs* How Many Licks? A7 Featuring – SisqoMixed By – Ed RasoProducer – Mario "Yellowman" Winans*, Sean "Puffy" 3:52 Combs*Recorded By – Dave WadeWritten-By – M. -

National Song Binder

SONG LIST BINDER ——————————————- REVISED MARCH 2014 SONG LIST BINDER TABLE OF CONTENTS Complete Music GS3 Spotlight Song Suggestions Show Enhancer Listing Icebreakers Problem Solving Troubleshooting Signature Show Example Song List by Title Song List by Artist For booking information and franchise locations, visit us online at www.cmusic.com Song List Updated March 2014 © 2014 Complete Music® All Rights Reserved Good Standard Song Suggestions The following is a list of Complete’s Good Standard Songs Suggestions. They are listed from the 2000’s back to the 1950’s, including polkas, waltzes and other styles. See the footer for reference to music speed and type. 2000 POP NINETIES ROCK NINETIES HIP-HOP / RAP FP Lady Marmalade FR Thunderstruck FX Baby Got Back FP Bootylicious FR More Human Than Human FX C'mon Ride It FP Oops! I Did It Again FR Paradise City FX Whoomp There It Is FP Who Let The Dogs Out FR Give It Away Now FX Rump Shaker FP Ride Wit Me FR New Age Girl FX Gettin' Jiggy Wit It MP Miss Independent FR Down FX Ice Ice Baby SP I Knew I Loved You FR Been Caught Stealin' FS Gonna Make You Sweat SP I Could Not Ask For More SR Bed Of Roses FX Fantastic Voyage SP Back At One SR I Don't Want To Miss A Thing FX Tootsie Roll SR November Rain FX U Can't Touch This SP Closing Time MX California Love 2000 ROCK SR Tears In Heaven MX Shoop FR Pretty Fly (For A White Guy) MX Let Me Clear My Throat FR All The Small Things MX Gangsta Paradise FR I'm A Believer NINETIES POP MX Rappers Delight MR Kryptonite FP Grease Mega Mix MX Whatta Man -

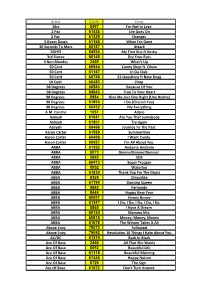

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Nathaniel Mary Quinn

NATHANIEL MARY QUINN Press Pack 612 NORTH ALMONT DRIVE, LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90069 TEL 310 550 0050 FAX 310 550 0605 WWW.MBART.COM NATHANIEL MARY QUINN BORN 1977, Chicago, IL Lives and works in Brooklyn, NY EDUCATION 2002 M.F.A. New York University, New York NY 2000 B.A. Wabash College, Crawfordsville, IN SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Madison Museum of Art, Madison, WI (forthcoming) 2018 The Land, Salon 94, New York, NY Soundtrack, M+B, Los Angeles, CA 2017 Nothing’s Funny, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, IL On that Faithful Day, Half Gallery, New York, NY 2016 St. Marks, Luce Gallery, Torino, Italy Highlights, M+B, Los Angeles, CA 2015 Back and Forth, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, IL 2014 Past/Present, Pace London Gallery, London, UK Nathaniel Mary Quinn: Species, Bunker 259 Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2013 The MoCADA Windows, Museum of Contemporary and African Diasporan Arts Brooklyn, NY 2011 Glamour and Doom, Synergy Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2008 Deception, Animals, Blood, Pain, Harriet’s Alter Ego Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2007 The Majic Stick, curated by Derrick Adams, Rush Arts Gallery, New York, NY The Boomerang Series, Colored Illustrations/One Person Exhibition: “The Sharing Secret” Children’s Book, The Children’s Museum of the Arts, New York, NY 2006 Urban Portraits/Exalt Fundraiser Benefit, Rush Arts Gallery, New York, NY Couture-Hustle, Steele Life Gallery, Chicago, IL 612 NORTH ALMONT DRIVE, LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90069 TEL 310 550 0050 FAX 310 550 0605 WWW.MBART.COM 2004 The Great Lovely: From the Ghetto to the Sunshine, curated by Hanne -

The Symbolic Rape of Representation: a Rhetorical Analysis of Black Musical Expression on Billboard's Hot 100 Charts

THE SYMBOLIC RAPE OF REPRESENTATION: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF BLACK MUSICAL EXPRESSION ON BILLBOARD'S HOT 100 CHARTS Richard Sheldon Koonce A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2006 Committee: John Makay, Advisor William Coggin Graduate Faculty Representative Lynda Dee Dixon Radhika Gajjala ii ABSTRACT John J. Makay, Advisor The purpose of this study is to use rhetorical criticism as a means of examining how Blacks are depicted in the lyrics of popular songs, particularly hip-hop music. This study provides a rhetorical analysis of 40 popular songs on Billboard’s Hot 100 Singles Charts from 1999 to 2006. The songs were selected from the Billboard charts, which were accessible to me as a paid subscriber of Napster. The rhetorical analysis of these songs will be bolstered through the use of Black feminist/critical theories. This study will extend previous research regarding the rhetoric of song. It also will identify some of the shared themes in music produced by Blacks, particularly the genre commonly referred to as hip-hop music. This analysis builds upon the idea that the majority of hip-hop music produced and performed by Black recording artists reinforces racial stereotypes, and thus, hegemony. The study supports the concept of which bell hooks (1981) frequently refers to as white supremacist capitalist patriarchy and what Hill-Collins (2000) refers to as the hegemonic domain. The analysis also provides a framework for analyzing the themes of popular songs across genres. The genres ultimately are viewed through the gaze of race and gender because Black male recording artists perform the majority of hip-hop songs. -

The Bands of Detroit

IT’S FREE! TAKE ONE! DETROIT PUNK ROCK SCENE REPORT It seems that the arsenal of democracy has been raided, pillaged, and ultimately, neglected. A city once teeming with nearly two million residents has seemingly emptied to 720,000 in half a century’s time (the actual number is likely around 770,000 residing citizens, including those who aren’t registered), leaving numerous plots of land vacant and unused. Unfortunately, those areas are seldom filled with proactive squatters or off-the-grid residents; most are not even occupied at all. The majority of the east and northwest sides of the city are examples of this urban blight. Detroit has lost its base of income in its taxpaying residents, simultaneously retaining an anchor of burdensome (whether it’s voluntary or not) poverty-stricken, government-dependent citizens. Just across the Detroit city borders are the gated communities of xenophobic suburban families, who turn their collective noses at all that does not beckon to their will and their wallet. Somewhere, in the narrow cracks between these two aforementioned sets of undesirables, is the single best punk rock scene you’ve heard nary a tale of, the one that everyone in the U.S. and abroad tends to overlook. Despite receiving regular touring acts (Subhumans, Terror, Common Enemy, Star Fucking Hipsters, Entombed, GBH, the Adicts, Millions of Dead Cops, Mouth Sewn Shut, DRI, DOA, etc), Detroit doesn’t seem to get any recognition for homegrown punk rock, even though we were the ones who got the ball rolling in the late 60s. Some of the city’s naysayers are little more than punk rock Glenn Becks or Charlie Sheens, while others have had genuinely bad experiences; however, if the world is willing to listen to what we as Detroiters have to say with an unbiased ear, we are willing to speak, candidly and coherently. -

Songs by Artist

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Artist www.adj2.com Title Title Title 10,000 Maniacs 50 Cent AC DC Because The Night Disco Inferno Stiff Upper Lip Trouble Me Just A Lil Bit You Shook Me All Night Long 10Cc P.I.M.P. Ace Of Base I'm Not In Love Straight To The Bank All That She Wants 112 50 Cent & Eminen Beautiful Life Dance With Me Patiently Waiting Cruel Summer 112 & Ludacris 50 Cent & The Game Don't Turn Around Hot & Wet Hate It Or Love It Living In Danger 112 & Supercat 50 Cent Feat. Eminem And Adam Levine Sign, The Na Na Na My Life (Clean) Adam Gregory 1975 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg And Young Crazy Days City Jeezy Adam Lambert Love Me Major Distribution (Clean) Never Close Our Eyes Robbers 69 Boyz Adam Levine The Sound Tootsee Roll Lost Stars UGH 702 Adam Sandler 2 Pac Where My Girls At What The Hell Happened To Me California Love 8 Ball & MJG Adams Family 2 Unlimited You Don't Want Drama The Addams Family Theme Song No Limits 98 Degrees Addams Family 20 Fingers Because Of You The Addams Family Theme Short Dick Man Give Me Just One Night Adele 21 Savage Hardest Thing Chasing Pavements Bank Account I Do Cherish You Cold Shoulder 3 Degrees, The My Everything Hello Woman In Love A Chorus Line Make You Feel My Love 3 Doors Down What I Did For Love One And Only Here Without You a ha Promise This Its Not My Time Take On Me Rolling In The Deep Kryptonite A Taste Of Honey Rumour Has It Loser Boogie Oogie Oogie Set Fire To The Rain 30 Seconds To Mars Sukiyaki Skyfall Kill, The (Bury Me) Aah Someone Like You Kings & Queens Kho Meh Terri -

Sex Trafficking Training for Social Workers

SEX TRAFFICKING TRAINING FOR SOCIAL WORKERS A Project Presented to the faculty of the Division of Social Work California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SOCIAL WORK by Kristy S. Coleman SPRING 2018 © 2018 Kristy S. Coleman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii SEX TRAFFICKING TRAINING FOR SOCIAL WORKERS A Project by Kristy S. Coleman Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Jennifer Price Wolf, PhD ____________________________ Date iii Student: Kristy S. Coleman I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. __________________________, Graduate Program Director ___________________ Serge C. Lee, PhD Date Division of Social Work iv Abstract of SEX TRAFFICKING TRAINING FOR SOCIAL WORKERS by Kristy S. Coleman This project involved the creation of a 60-minute training session for entry-level social workers to test the impact, according to them, on their level of preparedness to either prevent or intervene with survivors/potential victims of human trafficking. A multi- source research approach was taken to gather information from not only from academic sources, but also other relevant and credible sources—ranging from government to academic, journalist to pimp-published, experienced social workers to sex trafficking survivors, rap music to documentary videos—that would enrich the presented -

Family Law Toolkit for Survivors the Domestic Violence & Mental Health Collaboration Project

Family Law Toolkit for Survivors The Domestic Violence & Mental Health Collaboration Project Songs for Surviving the Family Law Process Listening to music is an effective way to distract yourself and to improve your mood. Music has been shown to decrease anxiety and depression. It also decreases the level of cortisol, a stress hormone in your body. Music can be motivational, driving you forward when you feel like giving up. This handout provides a list of songs selected to help you throughout the family law process. They are chosen for many reasons—some songs are motivating, others relaxing, some may just bring a smile to your face. The lyrics of these songs are about surviving and connecting with your inner strength. We chose a range of musical styles, so you can pick the songs that resonate most with you. You may also want to add your own favorites to this list. You can listen when you are feeling stressed, on your way to or from court, or daily as part of your self-care. For additional suggestions about reducing your stress and taking care of yourself throughout this process, check out the Coping Skills handout, speak with a domestic violence advocate (see Domestic Violence Advocacy Resources), or see a mental health service provider (see Mental Health Treatment Resources). “For me, music helps me cope. Music helps me when I am sad, happy, and even angry. I also use some songs to remind me that I am strong and capable and deserve the best life has to offer.” “Music helps me relax and I relate to the words in many songs. -

Download How Many Licks

Download how many licks LINK TO DOWNLOAD Have fun on the th or st day, or any other day, with this fun math activity. Students make predictions as to how many licks they think it will take to get to the center of the Tootsie Pop. How Many Licks is a popular song by Mango 95 | Create your own TikTok videos with the How Many Licks song and explore 0 videos made by new and popular creators. Next in your How Many Licks? download is a progress tally sheet that will really pump up the summer-lovin’. The idea behind this bad boy is to track how many ‘licks’ you get through before you score big (wink-wink). Aug 15, · An icon used to represent a menu that can be toggled by interacting with this icon. An image tagged how many licks. Create. Caption a Meme or Image Make a GIF Make a Chart Make a Demotivational Flip Through Images. renuzap.podarokideal.ru; IMAGE DESCRIPTION: HOW MANY LICKS DOES IT TAKE; TO SPOIL ENDGAME? hotkeys: D = random, W = upvote, S = downvote, A = back. Waptrick Lil Kim Mp3: Download Lil Kim - Lighters Up, Lil Kim - Whoa, Lil Kim - The Jump Off, Sisqo feat Lil Kim - How Many Licks, Lil Kim - Magic Stick, Lil Kim - Put It In My Mouth, Lil Kim - Get In Touch With Us, Lil Kim feat Mr Cheeks Timbala - The Jump Off, Lil Kim - Suck my Dick, Methods Of Mayhem feat Lil Kim - Get Naked, Lil Kim - Not Tonight, Lil Kim - No Time For Fake Ones, Lil Kim. -

Karaoke List

Artist Code Song 10cc 8497 I'm Not In Love 2 Pac 61426 Life Goes On 2 Pac 61425 Changes 3 Doors Down 61165 When I'm Gone 30 Seconds To Mars 60147 Attack 3OH!3 84954 My First Kiss ft Kesha 3rd Storee 60145 Dry Your Eyes 4 Non Blondes 2459 What's Up 50 Cent 60944 Candy Shop ft. Olivia 50 Cent 61147 In Da Club 50 Cent 60748 21 Questions ft Nate Dogg 50 Cent 60483 Pimp 98 Degrees 60543 Because Of You 98 Degrees 84943 True To Your Heart 98 Degrees 8984 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 61890 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 60332 My Everything A.M. Canche 1051 Adoro Aaliyah 61681 Are You That Somebody Aaliyah 61801 Try Again Aaliyah 60468 Journey To The Past Aaron Carter 61588 Summertime Aaron Carter 60458 I Want Candy Aaron Carter 60557 I'm All About You ABBA 61352 Andante Andante ABBA 8073 Gimme!Gimme!Gimme! ABBA 2692 SOS ABBA 60413 Super Trooper ABBA 8952 Waterloo ABBA 61830 Thank You For The Music ABBA 8369 Chiquitita ABBA 61199 Dancing Queen ABBA 8842 Fernando ABBA 8444 Happy New Year ABBA 60001 Honey Honey ABBA 61347 I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do ABBA 8865 I Have A Dream ABBA 60134 Mamma Mia ABBA 60818 Money, Money, Money ABBA 61678 The Winner Takes It All Above Envy 79073 Followed Above Envy 79092 Revolution 10 Things I Hate About You AC/DC 61319 Back In Black Ace Of Base 2466 All That She Wants Ace Of Base 8592 Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 61118 Beautiful Morning Ace Of Base 61346 Happy Nation Ace Of Base 8729 The Sign Ace Of Base 61672 Don't Turn Around Acid House Kings 61904 This Heart Is A Stone Acquiesce 60699 Oasis Adam