Can We Establish Predictable Trends in Quality of Life in Kaduna State and Nigeria?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

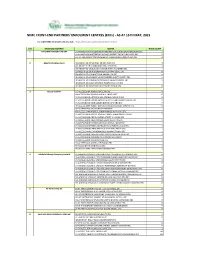

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Violence in Nigeria's North West

Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem Africa Report N°288 | 18 May 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Community Conflicts, Criminal Gangs and Jihadists ...................................................... 5 A. Farmers and Vigilantes versus Herders and Bandits ................................................ 6 B. Criminal Violence ...................................................................................................... 9 C. Jihadist Violence ........................................................................................................ 11 III. Effects of Violence ............................................................................................................ 15 A. Humanitarian and Social Impact .............................................................................. 15 B. Economic Impact ....................................................................................................... 16 C. Impact on Overall National Security ......................................................................... 17 IV. ISWAP, the North West and -

Wind Energy Evaluation for Electricity Generation Using WECS in Seven Selected Locations in Nigeria ⇑ O.S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Covenant University Repository Applied Energy 88 (2011) 3197–3206 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Applied Energy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/apenergy Wind energy evaluation for electricity generation using WECS in seven selected locations in Nigeria ⇑ O.S. Ohunakin a, , M.S. Adaramola b, O.M. Oyewola c a Mechanical Engineering Department, Covenant University, P.M.B 1023, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria b Department of Energy and Process Engineering, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway c Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria article info abstract Article history: This paper statistically examine wind characteristics from seven meteorological stations within the Received 12 November 2010 North-West (NW) geo-political region of Nigeria using 36-year (1971–2007) wind speed data measured Received in revised form 14 February 2011 at 10 m height subjected to 2-parameter Weibull analysis. It is observed that the monthly mean wind Accepted 18 March 2011 speed in this region ranges from 2.64 m/s to 9.83 m/s. The minimum monthly mean wind speed was Available online 11 April 2011 recorded in Yelwa in the month of November while the maximum value is observed in Katsina in the month of June. The annual wind speeds range from 3.61 m/s in Yelwa to 7.77 m/s in Kano. It is further Keywords: shown that Sokoto, Katsina and Kano are suitable locations for wind turbine installations with annual Mean wind speed mean wind speeds of 7.61, 7.45 and 7.77 m/s, respectively. -

Gusau Journal of Accounting and Finance, Vol

Gusau Journal of Accounting and Finance, Vol. 2, Issue 3, April, 2021 Gusau Journal of Accounting and Finance (GUJAF) Vol. 2 Issue 3, April, 2021 ISSN: 2756-665X A Publication of Department of Accounting and Finance, Faculty of Management and Social Sciences, Federal University Gusau, Zamfara State –Nigeria 1 Gusau Journal of Accounting and Finance, Vol. 2, Issue 3, April, 2021 BOARD COMPOSITION AND EARNINGS MANAGEMENT OF LISTED NON- FINANCIAL FIRMS IN NIGERIA Adeoye Lukmon Adewale Department of Accounting Osun State University, Osogbo [email protected] Olowookere Johnson Kolawole Department of Accounting Osun State University, Osogbo [email protected] Bankole Oluwaseun Emmanuel Department of Accounting Osun State University, Osogbo [email protected] Abstract In recent years, earnings management has gotten a lot of attention. This is owing to the fact that it is linked to the accuracy of published accounting reports. According to the academic literature, earnings management appears to be widespread among publicly traded firms. In response to calls for a higher proportion and composition of independent directors on boards and for the board of directors to be more financially sophisticated, the paper examined the effect of board composition on earnings management of listed non-financial firms in Nigeria from 2009 to 2018. Secondary data was used and extracted from various annual financial reports of the selected firms. The population for the study consisted of 117 listed non-financial firms in Nigeria as at December, 2018. This study used purposive sampling technique where 20 firms, whose data were accessible and available within the sample period of 2009 to 2018 were selected, being the most recent ten years within which the second corporate governance codes for quoted firms was introduced as a replacement to the 2003 SEC code. -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT FEBRUARY 13, 2019 S/N Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 4 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 5 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 6 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 7 Above Only Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Benson Idahosa University Campus, Ugbor GRA, Benin EDO Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank 8 Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi BAUCHI 9 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 10 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 11 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 12 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 13 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 14 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. Area, Nasarawa State NASSARAWA 15 Adazi-Enu Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Nkwor Market Square, Adazi- Enu, Anaocha Local Govt, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 16 Adazi-Nnukwu Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Near Eke Market, Adazi Nnukwu, Adazi, Anambra State ANAMBRA 17 Addosser Microfinance Bank Limited State 32, Lewis Street, Lagos Island, Lagos State LAGOS 18 Adeyemi College Staff Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Adeyemi College of Education Staff Ni 1, CMS Ltd Secretariat, Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo ONDO 19 Afekhafe Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit No. -

Urinary Schistosomiasis Among Vulnerable Children in A

Uchendu et al. BMC Infectious Diseases (2017) 17:487 DOI 10.1186/s12879-017-2591-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Urinary schistosomiasis among vulnerable children in a rehabilitation home in Ibadan, Oyo state, Nigeria Obioma Uchendu1,2* , Victoria Oladoyin2, Michael Idowu1, Oluwapelumi Adeyera1, Oluwatosin Olabisi2, Oluwafisayomi Oluwatosin2 and Gbemisola Leigh2 Abstract Background: Schistosomiasis is a disease of public health importance with long term complications mostly common among children, rural dwellers, poor and migrant workers. Studies have not documented the burden among migrant workers and their families. The study aimed to describe the burden of schistosomiasis and demographic characteristics among children of migrant workers residing in a rehabilitation home in Ibadan, Nigeria. Methods: A cross-sectional study using sixty six children, who were tested following complaints of haematuria by six of them. An interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect information on demographic and environmental characteristics of the children and urine microscopy, was conducted. Data was analysed using descriptive statistics and correlation. Statistical significance was set at 5%. Results: Mean age of respondents was 11.8 ± 4.0 years and 57.6% were males. The prevalence of schistosomiasis was 19.7% with preponderance among males (64.3%) and children aged 12 years and above (71.4%); 85.7% of infected children were from Kwara State; 78.6% waded in water body and 92.9% had red blood cells and pus cells on urine microscopy. Conclusions: The burden of schistosomiasis is high among children of migrant workers and they serve as reservoirs for transmission of the disease. Government needs to work synergistically with NGOs, FBOs and other partners to achieve schistosomiasis prevention and control among this particular group. -

Willingness to Pay for Cataract Surgery Is Much Lower Than Actual Costs in Zamfara State, Northern Nigeria

Willingness to pay for cataract surgery is much lower than actual costs in Zamfara State, northern Nigeria Nazaradden Ibrahim1 Jacqueline Ramke2 Francisco Pozo-Martin3 Clare E Gilbert4 1. Zamfara State Eye Care Programme, Ministry of Health, Gusau, Nigeria 2. Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand 3. Department of Global Health and Development, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom 4. International Centre for Eye Health, Clinical Research Unit, Department of Infectious & Tropical Diseases, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom Corresponding Author: Jacqueline Ramke [email protected] Dept of Epidemiology & Biostatistics, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, The University of Auckland. Private Bag 92019 Auckland Mail Centre Auckland 1142, New Zealand Conflict of interest: None of the authors have any proprietary interests or conflicts of interest related to this submission. Financial support: The study was funded by the Commonwealth Scholarship Scheme, Sightsavers UK and Hooper Scholarship. None of the funders contributed to the design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of data or in writing the script, or the decision to submit the publication. Running head: Willingness to pay for cataract surgery in Nigeria This submission has not been published anywhere previously and it is not simultaneously being considered for any other publication. ABSTRACT Purpose: Direct medical and non-medical costs incurred by those undergoing subsidised cataract surgery at Gusau eye clinic, Zamfara state were recently determined. The aim of this study was to assess the willingness to pay for cataract surgery among adults with severe visual impairment or blindness from cataract in rural Zamfara, and to compare this to actual costs. -

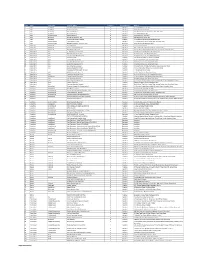

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. -

The Role of Nigerian Communication Commission 1MBASUA

Service Charges and Telecommunication Companies in Gombe State, Nigeria: The role of Nigerian Communication Commission 1MBASUA Ali Yakubu, 2GONGDEN Othniel Sunday & 3Dr. Fatima Inuwa Usman 1Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Gombe State University, Gombe State. 2Industrial Training Fund, Headquarters Complex, Jos 3Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Management Sciences, University of Maiduguri Corresponding Author: [email protected], [email protected] Tel: 08065131257 Abstract Telecommunication industry in today’s world has become a requisite tool in the entire globalization process of becoming a global village. This study investigated the extent of regulatory role of Nigeria Communication Commission’s on the service charges in telecommunication firms operating in Gombe State, Nigeria. The study adopted survey research design. The study is descriptive as well as hypothetical in nature. The study is a Non-contrived which is a natural setting in which work progress with minimal interference with a population of 172,871,094 subscribers from the four available networks (Airtel Network, Glo Nigeria, 9mobile and MTN Nigeria) in the State, while the sample size is 384. The hypotheses formulated were tested using multivariate analyses. The study concluded that, there is significant relationship between the variables and recommended as; the need to improve and sustain activities of the telecommunication firms in Gombe statem, in terms of monitoring and enforcement in their service charges. The regulatory bodies of the telecommunication firm in Gombe state should be pro-active in ensuring that the call charges for all firms are the same to maintain fair promotion of products. Keywords: Communication, Regulation, Service Charges, Telecommunication Introduction The world today is a global village given that telecommunication or communication industry at large has become a requisite tool in the entire globalization process. -

Access Bank Branches Nationwide

LIST OF ACCESS BANK BRANCHES NATIONWIDE ABUJA Town Address Ademola Adetokunbo Plot 833, Ademola Adetokunbo Crescent, Wuse 2, Abuja. Aminu Kano Plot 1195, Aminu Kano Cresent, Wuse II, Abuja. Asokoro 48, Yakubu Gowon Crescent, Asokoro, Abuja. Garki Plot 1231, Cadastral Zone A03, Garki II District, Abuja. Kubwa Plot 59, Gado Nasko Road, Kubwa, Abuja. National Assembly National Assembly White House Basement, Abuja. Wuse Market 36, Doula Street, Zone 5, Wuse Market. Herbert Macaulay Plot 247, Herbert Macaulay Way Total House Building, Opposite NNPC Tower, Central Business District Abuja. ABIA STATE Town Address Aba 69, Azikiwe Road, Abia. Umuahia 6, Trading/Residential Area (Library Avenue). ADAMAWA STATE Town Address Yola 13/15, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola. AKWA IBOM STATE Town Address Uyo 21/23 Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom. ANAMBRA STATE Town Address Awka 1, Ajekwe Close, Off Enugu-Onitsha Express way, Awka. Nnewi Block 015, Zone 1, Edo-Ezemewi Road, Nnewi. Onitsha 6, New Market Road , Onitsha. BAUCHI STATE Town Address Bauchi 24, Murtala Mohammed Way, Bauchi. BAYELSA STATE Town Address Yenagoa Plot 3, Onopa Commercial Layout, Onopa, Yenagoa. BENUE STATE Town Address Makurdi 5, Ogiri Oko Road, GRA, Makurdi BORNO STATE Town Address Maiduguri Sir Kashim Ibrahim Way, Maiduguri. CROSS RIVER STATE Town Address Calabar 45, Muritala Mohammed Way, Calabar. Access Bank Cash Center Unicem Mfamosing, Calabar DELTA STATE Town Address Asaba 304, Nnebisi, Road, Asaba. Warri 57, Effurun/Sapele Road, Warri. EBONYI STATE Town Address Abakaliki 44, Ogoja Road, Abakaliki. EDO STATE Town Address Benin 45, Akpakpava Street, Benin City, Benin. Sapele Road 164, Opposite NPDC, Sapele Road. -

Bayero University Kano (BUK)

BAYERO UNIVERSITY, KANO SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES FIRSFIRSTT BATCH ADMISSIONS OF 2019/2020 SESSION Faculty of Agriculture Department: Agricultural Economics and Extension Ph.D Agricultural Economics (Livelihood and Natural Resources Economics) Application S/N Invoice No. Full Name No. 1 DGBH 776 Ashafa Salisu SAMBO 2 TQJX 4560 Sesugh UKER 3 KQBL 8701 Nasiru Bako SANI Ph.D Agricultural Economics(Programme ID:1006) Application S/N Invoice No. Full Name No. 1 FRDZ 3835 Umar Karaye IBRAHIM 2 GTDJ 2099 Salmanu Safiyanu ABDULSALAM M.Sc Agricultural Economics (Livelihood and Natural Resources Economics) Application S/N Invoice No. Full Name No. 1 HDYQ 1451 Simon Okechukwu AGBO 2 QKGW 1814 Linda Imuetiyan IRENE 3 NVPD 2548 Mary Adebukola ALAMU 4 WBKX 3667 Muhammad Baba FUGU 5 ZXCL 4612 Mojisola Feyisikemi OLUFEMI 6 LNQT 4158 Hafsat Murtala SALIM 7 LRMT 6006 Usman Abdullahi IDRIS 8 RWMF 5114 Abdullahi Ibrahim DUMBULUN 9 DCVZ 8142 Yusuf MIKO GUMEL M.Sc Agricultural Economics(Programme ID:1002) Application S/N Invoice No. Full Name No. 1 KMLH 1927 Samir Hussaini USMAN 2 QZDY 1730 Mercy Oluwafunmike OLANIYI 3 WTGC 3166 Muhammad Imam IBRAHIM 4 DCQV 3116 Patrick Ojiya ADOLE 5 VPHQ 3788 Rukayya Rabiu YUSUF 6 RQXM 5855 Kassim Shuaib AUDU 7 TQMN 6574 Najiba Musa MUMAMMAD 8 ZLPT 7218 Daniel Jarafu MAMZA First Batch of 2019/2020 PG Admission List Page 1 of 168 M.Sc Agricultural Extension(Programme ID:1003) Application S/N Invoice No. Full Name No. 1 TKCX 6389 Asogah Solomon EDOH 2 MQPD 4837 Murtala SULE 3 HWZP 6307 Aminu Rdoruwa IBRAHIM 4 MRGT 6681 Ruth Nwang JONATHAN Department: Agronomy Ph.D Agronomy(Programme ID:1108) Application S/N Invoice No. -

Petrographic Study and Geochemical Analysis of Basement Rocks in Federal University Gusau and Its Environs, Zamfara State, Northwestern Nigeria Chinwuko, A

ogy eol & G OPEN ACCESS Freely available online G e f o o p l h a y s n r i c u Journal of Geology & Geophysics s o J ISSN: 2381-8719 Research Article Petrographic Study and Geochemical Analysis of Basement Rocks in Federal University Gusau and Its Environs, Zamfara State, Northwestern Nigeria Chinwuko, A. I., Danbatta, U. A., Ovwasa, M. O., Shaibu, I., and Shuaibu, A. M. Department of Geological Sciences, Federal University Gusau, Zamfara State, Nigeria ABSTRACT Petrographic and geochemical analysis of basement rocks in Federal University Gusau and its environs, Zamfara State, Northwestern Nigeria were carried out in order to unveil the major rock forming minerals as well as the textural relationships composition within the rock. The identified rock unit is granite and they are mainly whitish- grey in colour, with the majority of them having porphyritic-coarse-grained texture and minor with fine-grained texture. The light coloured crystals in hand specimens are the felsic minerals mainly quartz, and feldspars while the grey-dark crystals are the mafic minerals like the biotite-mica. The result of the thin section analysis depicts that the minerals present within the rock samples in the area: quartz (40%), orthoclase (40%) and biotite (20%). These identified minerals are classified as the major rock forming silicate minerals. The geochemical analysis result shows that the rocks are characterized by high percentage of quartz (SiO2) in the range of 77.4-98.2 wt% with an average of 84.87 wt%; subordinate amounts of hematite (Fe2O3) with an average concentration of 4.08 wt% as well as low concentration of K2O, CaO, TiO2, V2O5, MnO, NiO, CuO, ZnO, RuO2, In2O3 and other minor constituent oxides.